Recent scientific analysis reveal the “gold” of Giovanni Segantini, currently in Milan

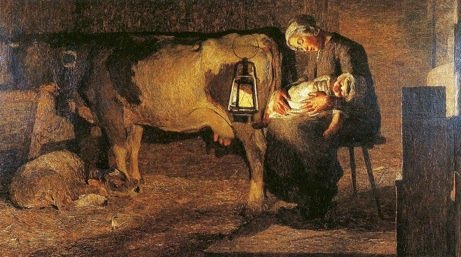

- 1. Giovanni Segantini, Le due madri, 1889.

- 2. Giovanni Segantini, Petalo di rosa, 1891.

- 3. Giovanni Segantini, Petalo di rosa, detail.

- 4. Giovanni Segantini, Cavalli al galoppo, 1988. Detail.

- 5. Giovanni Segantini, Pietà, 1890-92.

- 6. Giovanni Segantini, Pietà, 1890-92. Detail.

- 7. Giovanni Segantini, amore alla fonte della vita, 1896. Detail.

- 8. Giovanni Segantini, amore alla fonte della vita, 1896. Detail.

- 9. Giovanni Segantini, L’ora mesta, 1892.

- 10. Giovanni Segantini, L’ora mesta, 1892. Detail.

- 11. Giovanni Segantini, Donna alla fonte, 1893-94.

- 12. Giovanni Segantini, Donna alla fonte, 1893-94. Detail.

In the occasion of the comprehensive show dedicated to Giovanni Segantini currently at Palazzo Reale, in Milan, CFA’s contributor Gianluca Poldi, a physicist specialized in scientific methods of investigation on artworks, reports the enlightening yet unpublished results of his recent studies on Segantini’s use of gold.

Le due madri (Two mothers, 1889, Milan, Gallery of Modern Art) [FIGURE 1] is one of the masterpieces of Giovanni Segantini’s body of work: in the light that spreads from the lamp, a calf sleeps under its mother and an infant in swaddling clothes sleeps in the arms of his own mother. The environment is being investigated by light and even every straw assumes an unexpected dignity and an impressive solidity.

In this humble and intimate setting an unsuspected discovery was made a few years ago: the straw hides gold fragments, as I could discover with proper scientific analysis.

This painting and many others by Segantini can currently be seen at Palazzo Reale, Milan. The monographic exhibition, extremely rich, excludes the possibility of contextualizing Segantini’s work within his period of time, instead pointing to show the evolution of his art and the importance of drawings in his artistic process, also to re-think and re-produce his subjects.

For his Milanese context the visitor should go to the Gallery of Modern Art in Via Palestro (free entry) and carefully observe what the Milanese Scapigliatura did in the 1870s-80s, influencing the very initial activity of Segantini, then what other divisionists did in the 1890s and later: Longoni, Morbelli and Pellizza da Volpedo, more involved with social themes, or Previati more linked to symbolist subjects.

Among his colleagues of the first Divisionism Segantini was the only one to use gold, and in such a large range of ways.

He applied it in golden leaves, requested to his merchant Alberto Grubicy several times in the 1890s. We see gold in the extraordinary Petalo di rosa (Rose petal, 1884-1890, Private collection), where his model was his partner Bice, applying it in her hair, in the headboard of the bed in the background and also, with a marvelous intuition, inside her irises [FIGURES 2-3]. In a similar way he used it in the blonde hair of the mother and child of the L’angelo della vita (The angel of life, 1894, Milan, Gallery of Modern Art), partially mixing it with brown and yellow colors. In the latter, some traces of silver are probably related to the gold leaf alloy.

Other times the artist applied a different modality in using gold, probably mixing gold powder in order to use the brush: like in the Cavalli al galoppo dated 1888 (Galloping horses, Private collection) [FIGURE 4] that is clearly a study for a proto-divisionist composition placed nearby on the same wall. Other examples can be found in the unpainted edges of some paintings, with golden brushstrokes on a red-brown base, like the unfinished “medallions” for the Triptych of the Nature.

Segantini employed gold also in his drawings, mainly charcoal on paper, to pursue peculiar effects of chiaroscuro and also – I believe – to remark the idea of preciosity of his work [FIGURES 5-6]. He was quite obsessed with a high style of life, although he lived retired in his chalet in the Maloja Pass, where we can still see his sets of dishes and crystal glasses with the thick GS monogram applied in gold.

However, perhaps, the most intriguing use of gold, the most uncommon, was under the color: typically found under meadows and mountains, but not under the skies, as we can notice at a closer look.

I.e. in the famous L’amore alla fonte della vita (Love at the spring of life, 1896, Milan, Gallery of Modern Art) gold can be found under the head and the wing of the angel [FIGURE 7], as well as under the grass [FIGURE 8], probably applied in gold leaves, possibly chopped. A similar technique was employed for other 1890s’ paintings, for instance L’ora mesta (Sad time, 1892, Private collection) [FIGURES 9-10] or Donna alla fonte (Woman at the fountain, 1893-1894, Winterthur, Museum Oskar Reinhart) [FIGURES 11-12].

Gold was used as a symbol and also, of course, as a peculiar tool, to get some reflection and a particular glare, barely hinted behind thin threads of color, forcing the observer to a high degree of concentration and keen observation. Gold reminds us of the value attributed by this artist to Nature, to the Alps and to the people living there, to the work in the fields, as well as suggesting how Nature has and can indeed reveal an inner light.

At a certain point of their personal considerations on divisionist technique, Longoni and Pellizza evolve to a kind of partial fusion of their brushstrokes, a sort of re-composition of that pure color that they wanted to keep into separate brushstrokes placed next to one another.

Segantini seems to move into the same direction, with his thick complex refined matter and colors mixed through their dense matching on the canvas.

He died at 41 while painting in his beloved peaks of the Engadine. How he might have painted afterward is a pure matter of speculation: his solid weave of light and nature is simply enough.

November 25, 2020