Don’t touch: Surface Value? Pennacchio Argentato, May Hands and the Sansevero Chapel in Naples

- Giuseppe Sanmartino, Veiled Christ, 1753, Sansevero Chapel, Naples.

- May Hands for LRRH_art editions by,, Meloni Meloni 5, 2014, digital & screen printed, hand embroidered & fabric layered, silk tapestry, 214 x 135. Courtesy of T293.

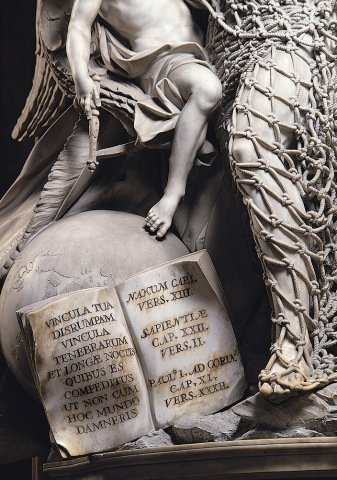

- Francesco Queirolo, Disillusion, 1753-54, Sansevero Chapel, Naples. Detail.

- Pennacchio Argentato, installation view, 2014. Courtesy of Wilkinson Gallery.

A brief but highly rewarding, and thought provoking, weekend visit to Naples for a pair of exhibitions from Gallery T293 also afforded an opportunity to see the Baroque marble sculptures in the Sansevero Chapel.

Arriving in the city on a Friday afternoon we visited the financial advisors’ offices of the Fideuram Bank in Piazza dei Martiri to see Pennacchio Argentato’s off-site project called Gateway which T293 informs us, “is the first of a series of curatorial interventions organized to reflect upon the potential of art in the context of conceptually relevant places”.

Wall mounted panels (all approximately 1.5 x 1.0 meter and thus constructed on a human scale, not too big or too small to engage with comfortably) and freestanding human body sections by Marisa Argentato and Pasquale Pennacchio were displayed throughout the offices and an interlinking corridor without interfering in the normal function of the space. The artists had intervened in this unorthodox setting for a conceptual project (though not for contemporary art, as financial institutions can access the most contemporaneous art forms) in a conventional presentation that avoided any uncomfortable confrontation, so as to allow the viewer thinking space. The intervention was not so much ‘site specific’ (we have seen this work before in ‘Time To Rise’ at Wilkinson Gallery in London) but conceptually engaged. Here was an opportunity for works that reference ‘Techno-Aesthetics’, the human experience in the Big Data age, and human perception that is now dwarfed by machine/computer technologies, to be installed in an apt alternative to the gallery – though Silicon Valley might be the ultimate site for these and future works.

Whilst both sets of sculptures had visual impact in terms of physical form, the surface qualities, especially of the wall mounted pieces that suggested paintings but are clearly sculptures, were strongly engaging. Several examples with the title ‘Alternate Future’ made in acrylic resin, paint and steel were especially attractive on the eye for a fusion of surface and form. The partly folded and crumpled surfaces have an animated quality that suggests a paused moment, frozen for the viewer. The T293 press statement explains that, “these objects bring about feelings of nostalgia and displacement, forcing us to question what are the patterns that make us human in a world that is constantly perceived through technological frames of references and politics of exchange.”

Useful advice, but of course, it is for our imagination, as well as our intellect, to respond to these sculptures, especially when presented in a context that does not constitute the usual ‘white cube’ of the gallery. A financial institution implies the fiscal marketplace and investment in an unpredictable and unstable future, where revolutionary digital and systems technologies are both deepening and expanding human possibilities for social order and well-being. For an engaged audience these works prompt a discussion about signs/sites of human and systems activity, and exponential processes of change in so-called ‘post-human’ worlds. This was essentially achieved through the aesthetic, material qualities of the sculptures and, in the ‘Alternate Future’ wall pieces, a surface presence that suggested a potential for an interrogation of uncertainty and an arrested unfolding of form.

However, a visit the following day to The Sansevero Chapel, to see the Veiled Christ (1753) by Giuseppe Sanmartino, memory of the surfaces of the ‘Alternate Future’ sculptures contrasted with the experience of viewing the finely chiseled and polished surface of this astonishing, devotional sculpture.

With the Vault ceiling fresco (‘The Glory of Heaven’), of Francesco Maria Russo (1749) above us, and the Floor Labyrinth (1765-1771) by Francesco Celabrano beneath our feet, the marble figure of the dead Christ engages the viewer in an otherworldly spiritual context, albeit in an environment created with great financial wealth. Some may find the overblown grandiosity of the Baroque age too close to kitsch at times, but the famed transparent qualities of the marble that appears to lay over this very human corpse brings us back to earth: back to ourselves. Here, the undulating, seductive topography responds to the human form, tantalizingly quite feminine, weighed down by gravity, but seemingly draped over an unnerving and frightening, lifeless repose. This milky, marble surface appears to transcend experience beyond Sanmartino’s extraordinary technical skills and to suggest that all is an illusion in our mortal world (as in vanitas and momento mori painting). This is a surface that one wishes to touch, as sight is not enough. A tactile sensation is sought with the hand, but denied by the conventions of viewing art, to test an assumption that this cannot be stone but is a silk-like shroud that astonishes the viewer.

Religious works, and predominantly secular modern art commentaries on the realities we construct, can both contain notions of the sublime, and may be awe inspiring, but in markedly different conceptual contexts and materials. The natural sublime is now augmented by the technologically transcendent.

Our second T293 visit of the weekend took us to the gallery itself, virtually hidden, but well worth finding, in via dei Tribunali. T293 presented a collection of art/textiles pieces entitled ‘Meloni Meloni’ by British artist, May Hands. The collection, referred to as an edition, was made in collaboration with the LRRH_art project (founded in 2009 by Daniela Goergens) based in Cologne and Berlin. This body of work consisted of almost a dozen textile art works, each individually and uniquely constructed and crafted with textile techniques (including embroidery and various stitchings), manual screen-printing and digital reproduction on silk.

Conceived and designed to be worn as sculpture, perhaps draped around the body; or displayed as artworks, this dual-intention references Robert Rauschenberg’s dictum that he wanted to work “in the gap between art and life” – although here there is no gap, but a realisation that ‘art’ and ‘life’ are inseparable. The subject matter is derived from the everyday consumer world, which, as the T293 press release tells us, “…elements of our daily visual environment are alienated and rearranged to form an alternative emotional experience for an upgraded aesthetic and tactile reality.”

These colourful and tantalisingly touchable objects/artworks were suspended from, and between, white walls in the multi-roomed gallery space. Critically, some pieces could have been displayed a little further from the walls to allow access behind, but given the tightness of the space an impressive and visually joyful experience had been created by the curators.

As with the works in ‘Gateway’, and the sculptures in the Sansevero Chapel, the seductive, eye-candy materials and images in ‘Meloni Meloni’ encompassed a potentially loaded meaning for the viewer to ponder in response to a range of materials, forms and surface qualities.

June 24, 2021