Venice Biennale 2015: at Corderie it’s about time to reactivate the selling office

- Terry Adkins.

- Tea Djordjadze.

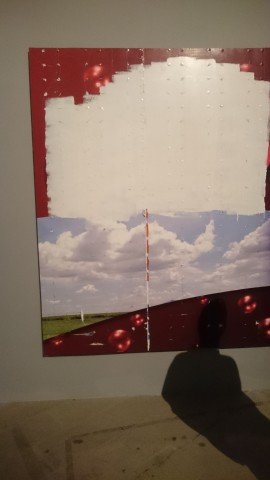

- Katharina Grosse.

- Oscar Murillo.

- Helen Marten.

- Kay Hassan.

- Gedi Sibony.

At the gate of the international exhibition at the Corderie an ambitious introductory text informs the general public and collectors about the three “intersecting” filters at their disposal “to reflect on both the current state of things and the appearance of things”. Probably reminding to Instagram’s tools more than to Sergei Eisenstein’s dialectical approach to montage, these three filters are Garden of disorder, Liveness: On Epic Duration, and Reading Capital. The text also advises of the fact that the three filters can be overlapped, and it seems an effective response to that idea of continuity between artworks and art practices that characterize the first part of the international exhibition, at the Giardini.

Unfortunately at the charming Corderie too only basic information are provided about the single artworks. It is not a big problem, thanks to the handy filters of course, but also to to the amount of known names and signature artworks on show, starting from the the collection of Bruce Nauman’s neon writings and Adel Abdessemed’s water lilies that welcome the visitor in the dark exhibition’s anteroom.

Then the light becomes warmer, and the first artwork you meet is Terry Adkins’s high column obtained by superimposing bass drums. The object-based installation immediately recalls the giant sculpture by Roberto Cuoghi presented in the last edition and sparks that insistent feeling of déjà vu which will stay with us until the end, when we will finally realize the real problem of this show or, more in general, one of the issues contemporary art will have to face in the next years: as stated by Director Paolo Baratta himself, contemporary art is getting old and, we may add, probably also too perfect even for those who love that sort of perfection you may find at art fairs and main institutions.

For the kind of very well-informed audience the social networks era is producing, to admire important artworks by acclaimed artists of today such as Gedi Sibony, Helen Marten, Tea Djordjadze, Pino Pascali, Katharina Grosse, Theaster Gates, Huma Bhabha, Oscar Murillo can be neither a discovery nor a surprise. On the contrary, it is the final validation of expected visual, cultural and economic values created during the last decade and now largely accepted by the art community. But wasn’t avant-garde art about research, discovery and innovation? Would a celebrated father of what we still call contemporary art such as Marcel Duchamp be happy to be trapped in a caption which indicates, among the essential information about the work, also where to go if you want to purchase it for your collection?

Of course Duchamp is not here to reply, and we don’t want to say that the Venice Biennale, or art in general, is opening too much to the business. Money are necessary to art as much as art is necessary to them. But in any case what matters is to speak clearly and probably this important side of the Venice Biennale should be considered a fundamental opportunity at any level. In origin there was an official Selling Office (Ufficio vendite), that was abolished in the edition that took place in 1970 in response to that commodification of art that artists and intellectuals were tackling at that time. Would this be a fair and honorable way to finally turn the page on the Curiger/Gioni/Enwezor’ successful trilogy? Today contemporary art needs to be conserved, not conservative minds to keep it static.

May 7, 2015