Is really Giotto we are looking at?

e’ve been to Palazzo Reale in Milan to visit the first comprehensive exhibition dedicated to Giotto. But the way the artist’s works have reached our days has indeed to be taken into account.

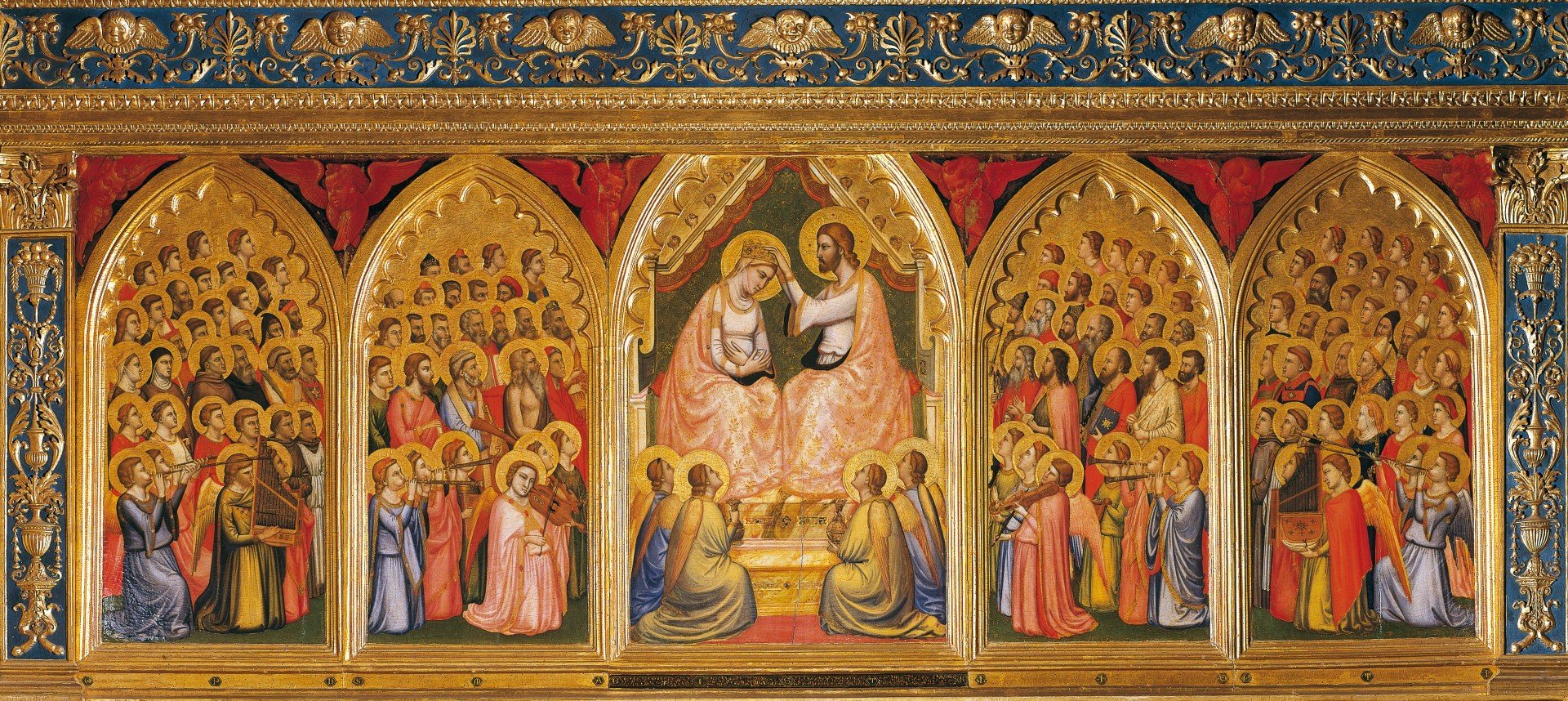

To have such a large number of works by the great Tuscan artist in a single exhibition is as rare as spotting a comet, or witnessing a total eclipse of the sun. But “Giotto, l’Italia” – at Palazzo Reale in Milan until January 2016 – is a must visit not only for this evident reason. It is also a fundamental occasion to rethink the figure of Giotto, and to ponder over his paintings, those which have reached our time after seven centuries of repainting, damages, and restorations; or those which have uncannily disappeared. Despite these queries being very clear in the mind of Giotto’s experts, they may be overlooked by the main public, thus preventing it to aptly frame the artist and his work.

Giotto is not a myth.

Stemming from the famous anecdote of his perfect circle (O) and from the way Vasari described his career and his work, the Tuscan master has been surrounded by the aura of genius. The art scholars have somehow followed this path until nowadays. The identification of the various local schools founded by Giotto (from Florence to Rome, Assisi, Rimini, Naples) unearthed some of his followers, conveying the idea that wherever the master came, an aesthetic revolution would occur thus unsettling places, styles and indeed minds. On the contrary, we are aware that in all those Italian places the artists did keep on being themselves. While the influence that Giotto played on other artists has often been investigated, little do we know about the other way round. How could Giotto have remained unmoved by such different painting styles in Naples or Rome, for instance? Could he possibly have adsorbed anything from local artists? Of course so. And many specialised studies have partially proved it. What is missing however it’s a systematic approach to this topic, which could perhaps bring back into focus minor local masters, today disregarded both by the public and by the market, who however have played a noteworthy role in Giotto’s revolution.

Giotto as Koons, Eliasson or Hirst.

A spin off of the above-mention subject is that of the one man show. When we think of Giotto in his trips around Italy, we tend to picture a man with colours and brushes, who alone would get to work in each site, with little help. However, history of art does teach us that this was not the case. First of all, it would have been physically impossible for the artist to carry out by himself all those ventures that we tended to attribute to him. Secondly, if he had had to entirely deal with each work alone, he would have had to give up some important commissions. As the curator of the Milanese show Serena Romano suggested, we ought to imagine Giotto within an entrepreneurial dimension, exactly as how today’s leading architecture firms work, that is producing projects which are identified by the name of the firm but are actually executed with a lot of leeway by collaborators. Not everything then is by Giotto.

A covered Giotto to discover?

Possibly the most attractive enigma is the one surrounding a Crucifix entirely repainted in the XVII century, which may be hiding a work by Giotto. Currently the piece is housed at the Grand Séminaire of Issy-les-Moulineaux, not far from Paris. In 2009 a team of scholars has carried out analyses of the work with x-rays and cleaning samples, thus identifying strong analogies with the work by the Tuscan master. When the owners decide to clean the painting from its 1600’s covering, will it possibly pop up a new piece by Giotto?

Too many hands on Giotto.

Lets take as an example “La Madonna con bambino in trono e angeli” of 1288ca, on show in Milan, a tempera and gold leaf on wood. Besides the fact that the piece had previously been considered not by Giotto, recent studies have demonstrated how the work was assembled before the board had been cut. The cut is certainly significant to the eyes of a modern viewer. By narrowing the background of the painting, you actually increase the focus on the central figure, who as a consequence acquires a charm which originally wasn’t there, that is when the viewer wasn’t just seized by the Virgin’s eyes. The way Giotto’s works have reached our days, through repainting and modern restorations, has indeed to be taken into account as it does influence our perception of the piece. To the extent that we could legitimately wonder how the works originally did look like. An answer could perhaps come up after the analyses of the frescos in the Peruzzi’s chapel. A research presenting the results of this study is about to be published (thanks to a scientific campaign by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure di Firenze and to the support of the Getty Foundation in Los Angeles).

November 17, 2022