Adriano Pedrosa and the the MASP: an interview

Adriano Pedrosa discuss with CFA his quest to make the MASP multiple, diverse and plural museum. And how to bring back its legacy

The Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) was founded in 1947 by Brazilian entrepreneur Assis Chateaubriand. At first headquartered in downtown São Paulo, in 1968 the museum switched to its current Avenida Paulista location, occupying a building designed by architect Lina Bo Bardi specifically to host MASP’s collection. In addition to designing the building, Bo Bardi also introduced a radical display methodology, whereby paintings were hung on glass easels along the room, allowing the viewer to establish a closer relationship with the works. Lina’s husband, Pietro Maria Bardi, served as MASP’s director from its inception until the early-1990s. In 1996, the then chief curator removed the museum’s signature display, adopting a more conventional model.

You were appointed artistic director of MASP a little over a year ago, and in this brief period of time you brought remarkable changes to the institution, such as the re-introduction of the glass easels, which generated great debate, particularly within the national artistic community. Is the return of the easels something meant to be temporary, permanent or occasional?

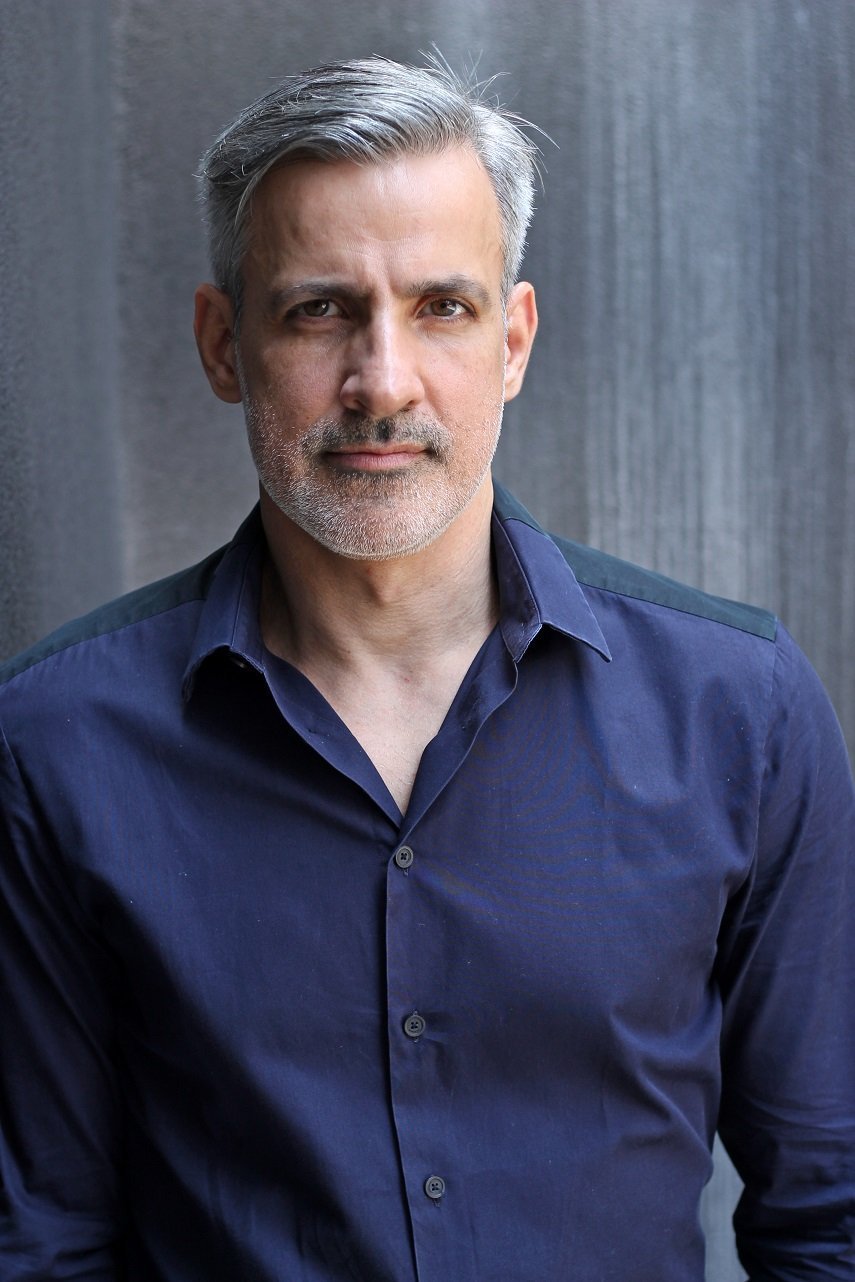

Adriano Pedrosa assumed the role of artistic director of MASP in November 2014, and within one year he brought back the iconic glass easels. Prior to this role, he had organised several exhibitions and publications in Brazil and abroad. Recent projects include the 31st Panorama da Arte Brasileira—Mamõyaguara opá mamõ pupé (Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo, 2009), the 12th Istanbul Biennial (2011), Conversations in Amman (Darat Al Funun, The Khalid Shoman Foundation, 2013), artevida (Casa França Brasil, Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, Escola de Artes Visuais e Cavalariças do Parque Lage, Biblioteca Parque Estadual, Rio de Janeiro, 2014) and Mestizo Histories (Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, 2014), to name but a few. In late February 2016, Pedrosa spoke with Conceptual Fine Arts about MASP’s history, its present moment and the challenges ahead.

Adriano Pedrosa: It’s long term. I cannot say it’s permanent because we will not be there forever. But we intend to maintain the glass easels display for a very long time.

For this particular show that reintroduces the easels, what were your criteria to select the works?

Adriano Pedrosa: The current display has about 119 works. The first criterion was taking into consideration the core of the collection, which is Figurative art. There is Abstract art in the collection, but it was not a focus of the collecting principles of Pietro Maria Bardi when he began in 1947. MASP’s is considered the strongest collection of European art outside Europe – and North America, for that matter – so of course we looked at the core of it. But we also wanted to slowly start gathering pieces from outside the European and the Brazilian canonical art history. That’s why there are artists such as José Antonio da Silva, who was already in the collection, or Agostinho Batista de Freitas, who had a close connection with Bardi since the beginning, or also Maria Auxiliadora. She was featured in a group exhibition in 1975 called Festa de Cores (Feast of Colours), and she was on the cover of the exhibition catalogue. So there are certain visionary artists working outside of the orthodox circle of art and its market who are generally called…

…Naive?

Adriano Pedrosa: Yes, the kind of nomenclatures that today we avoid: naive, primitive, and so on and so forth. These artists were already of interest to Bardi, and you can see that in the programme, as well as in the collection – Maria Auxiliadora’s painting in the MASP’s collection was actually a gift from Bardi himself. He had given it to the museum. And we went on to buy another painting by her last year, which now is on exhibition. But this is becoming a very long answer…

It’s very interesting, please go ahead.

Adriano Pedrosa: I wanted to speak a little bit more about the idea of the selection. The exhibition is called Picture Gallery in Transformation, which in Portuguese would translate as Pinacoteca em Transformação. In Dulwich, for example, you have the Dulwich Picture Gallery. In São Paulo we have the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo. However, we decided to title the show Acervo em Transformação, for Pinacoteca em Transformação would sound too similar to Pinacoteca do Estado. So actually the English title is more accurate, because it’s really the picture gallery, a space that is in transformation. And it is in transformation not only because we are introducing a new display, but also because we have the desire to continue to make changes. After having selected 119 works for the picture gallery, we realised that we could fit in quite a few more, maybe another thirty or forty.

Are you talking about a next step in the display?

Adriano Pedrosa: Not exactly. It’s rather a display that is always in transformation. We would like to make changes, insert different things, once a month maybe.

Are the artworks placed in a chronological order?

Adriano Pedrosa: Yes, they are. As you enter the room you encounter the oldest piece, and it goes like a sine wave, a serpentine, and then you have the very last piece here, which is the only 21st century artwork on display. It is a work by Marcelo Cidade about the fate and the past of the whole picture gallery itself. As a matter of fact Lina writes in her papers about the possibility of chance encounters between works; so they wouldn’t follow a traditional narrative, or a traditional art historical chronology.

That is also something that your current display allows, isn’t it? You envision it as being kind of a zig-zag, but the viewers will not necessarily follow it like that.

Adriano Pedrosa: Yes, it’s just a way to organise it. In the original display there were groupings of schools and movements, so you had the French artists, the Dutch artists, the Spanish artists, the Italian artists and the Brazilian artists, all gathered together in clusters. I feel that the idea Lina had and she was writing about never really came into being.

So, what has been your approach in this regards?

Adriano Pedrosa: We wanted this whole narrative to be more plural, more diverse, more open. Our challenge is to insert non-European works in the display up until the mid-20th century, and to insert non-Brazilian works in the display from the mid-20th century onward. We are interested, for example, in Cuzco paintings, that is 17th century; so you have a non-European presence in this century. Or, we are also interested in Marajoara, a Pre-Columbian society from the Brazilian part of the Amazon, known for its elaborate pottery. Then we would insert something here, around 15th and 16th centuries. We would also like to establish a more intense relationship with art of the last forty years, since at the moment we only have one piece from the 21st century. And before that there is just a piece by Maria Auxiliadora from 1974.

How are you planning to fill this massive gap?

Adriano Pedrosa: Well, we don’t have an acquisition budget, so it makes things a bit easier because there are some limitations (laugh). But we work a lot with donations, either from artists or collectors.

Are they responding well to the changes?

Adriano Pedrosa: Yes, they are. Well, we are not acquiring hundreds of pieces, but we got some positive responses.

Are you going to deal with Abstract art too?

Adriano Pedrosa: Although we have, for instance, some important pieces by Willys de Castro or Tomie Ohtake, the idea of not dealing with Abstraction is due to the fact that it is just a whole other narrative.

But then with Marajoara, for instance, it goes a bit abstract.

Adriano Pedrosa: Marajoara often has facial expressions. Anyhow, the narrative of Geometric Abstraction is such an important one in 20th century Latin American Art History that not attempting to deal with it is already a position.

Is this somehow a statement?

Adriano Pedrosa: I’m not ignoring it. It’s just acknowledging that this is an important narrative. But we are not going to go into that race to try to get those pieces; it’s a story that is very removed from the stories we can tell. In the end we say that the collection is the history of its own construction. It’s interesting that you asked about Marajoara, for we are researching about someone like Rubem Valentim, whose pieces can be regarded as emblems. We would find some other ways to touch upon the issue of Abstraction.

How did you re-design the museum’s programme?

Adriano Pedrosa: The first year – up until now in fact – was just dedicated to collections. And we are coming to understand MASP as a museum that is múltiplo, diverso e plural. This is the expression that I’m using, multiple, diverse and plural. In that sense, it has several collections of Asian art, African art, Costumes and Fashion, Photography; there is a collection of Brazilian and European art and a small collection of Pre-Columbian art that we would like to develop. We also have a very singular collection of about two thousand Kitsch objects, and there is a vast collection in the archive, of about half a million pieces, as well as a collection of drawings made by patients of a Psychiatric Hospital. We organised a show last year (Histories of Madness, with drawings made by patients from the Juquery Psychiatric Hospital), and then we have also found a collection which is not listed as art, but still is in the archive. It’s a group of drawings made by children who have been through different workshops at the museum. Thus although I’m coming from Contemporary art, Contemporary art is a smaller part of a larger panorama.

What does you current exhibitions aim at?

Adriano Pedrosa: We are looking at the history of the institution, which will turn seventy next year. And, as I said, we have half a million documents in the library. Everywhere we look there are vast histories and archives. For instance, when we did Art from Italy, Art from France, Art from Brazil we used many documents from the archive placing them next to the artworks. We carried out a sort of archaeology of the archives. But, as I said, we are currently interested in specific moments of the history of MASP. Playgrounds, for example, is an important exhibition that Nelson Leirner did in 1969 at the vão livre, the signature plaza underneath MASP’s building. At the end of 2014 I visited the artist in Rio to discuss with him our idea to eventually re-stage that show. But today the space under the museum does not belong to the museum any more, and there is a traditional fair taking place there every Sunday.

Are you planning other exhibitions at the moment?

Adriano Pedrosa: Anyhow, this is an exhibition that we are now revisiting. Its new version is called Playgrounds 2016. We invited six artists and collectives to respond to this idea of the playground. In parallel to that, we are organizing the first group exhibition which investigates a series of histories, which in a way comes from História mestiças (Mestizo Histories, a show Pedrosa made with Lilia Schwarcz at the Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, in 2014). This exhibition tried to explore cultura material (material culture) in a different way than that, for instance, of traditional anthropology: material culture as being able to tell histories other than Art History. So last year we started these two projects, the first titled Histórias da loucura (Histories of Madness), which is considered as the first chapter of an ongoing project. And in April Histórias da infância (Histories of Childhood) will open. Also Carla Zaccagnini’s exhibition (Elements of Beauty: A Tea Set Is Never Just a Tea Set, 2015/16) can be placed within a framework we call Histórias feministas (Feminist Histories).

Are these exhibitions somehow related to the museum permanent collection?

Adriano Pedrosa: Yes, they talk to each other. Histórias da infância, for instance, stems from the iconography of childhood in European painting, but around that we will also bring many objects from other schools, movements, territories. That is to say Brazilian art, Contemporary art, Video, the so called arte popular (literally ‘Popular art’, though the terminology is complicated), arte sacra (Religious art), ex-voto. We are also trying to establish connections through what we call mediation, or education programmes, as well as developing projects that are more multidisciplinary and not necessarily restricted to the context of Art History. What other histories can we tell, or can we address, with these objects? This is a question of high interest to us. Trying to investigate these histories, which are open and in process, is a very distinct mark of our programme. They are not all encompassing, totalising histories. This is why they are plural in that sense; we go back to the múltiplo, diverso e plural. Histórias in Portuguese, more so than in English, but much like in French, Spanish and Italian, can mean both the fictional and the non-fictional. We have história em quadrinhos (literally ‘story in tiny squares’, meaning comics), história pessoal (both personal history or personal story), história ficcional (fictional story), as well as political history.

What are your main challenges ahead?

Adriano Pedrosa: There are still quite a lot of structural and financial challenges in the museum itself, but also with regards to the programming. Of course, as time goes by we’ll be able to organise things well in advance, particularly to allow more time for research and reflection. I guess that is really our main challenge. Then we are trying to develop the connections, in order to make the MASP more plural, diverse and multiple. And to keep the picture gallery alive and in transformation is something that needs to be done.

To give continuity to this project is already a big challenge. It really divided the artistic community, with some respected thinkers opposing the idea, accusing it of being nostalgic, for instance. How do you perceive the criticism?

Adriano Pedrosa: It’s a very polemic display, and it still is, I would say, the most significant alternative to traditional exhibition display. There is a radicality to it which is just extraordinary, and there are many political implications in that model. It’s not just stylistic, it’s not just formal: when you take paintings off the wall, and you put them on the floor, they become more familiar, they become closer, so you have a different type of relationship. I became quite interested in life-size portraiture, because it allows people to place themselves behind the portrait and take pictures. This is a way of appropriating the paintings. In that sense, of course, this is something that was already very much present in Lina’s texts, you find the idea of desacralisation of art. And of course there are limitations. it’s mostly devoted to pictures, pictures of a certain dimension. You can’t have something that is three metres tall, for example, in a glass easel.

Do you have any large works in the collection?

Adriano Pedrosa: There is one that comes up in the discussion a lot. In the early 2000s, there was a report written by the then chief curator and the former chief curator, who made a list of many of the masterpieces that could not hang in the glass easels. But we managed to hang most of them, because we made the easels 10 or 20 centimeters taller. This is such a radical model, and it changes the way people relate to and perceive art.

As proved, we may add, by some leading art museums, where artworks are also displayed in the open space, instead of being hanged on the walls.

Adriano Pedrosa: Yes, for example by the Louvre Lens, in France. And it’s a model that was developed in our museum. So for me it’s obvious that we need to work with it and try to develop it. It’s somehow a decolonizing tool. And for a long time it was said that the model was never imitated elsewhere, but after it was brought down in 1996, several exhibitions actually reconstructed this display model. Then the Louvre Lens which is a project of SANAA, did something that is very much inspired by the MASP’s picture gallery, with nothing on the walls, and a room full of easels. But they are opaque easels, with a white background. They are not as radical as the ‘see-through’ glass. So for me it’s rather obvious that if you have a model, that was developed in your museum and it’s the only alternative display model of its kind, and it gives you singularity, and it gives you so much potential… Why would you throw this away?

April 29, 2024