Richard Feigen: a seminal interview

Master art gallery owner Richard Feigen sat down with us to talk about the future of the old masters and contemporary art at the Met.

Regarded as an one of the most influential art dealers on the art scene since the end of the Second World War, Richard Feigen helped to build main collections such as those of Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Mellon, Saul Steinberg, Baron Hans-Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Rose and Norton Neumann, not to mention former Sotheby’s Chairman A. Alfred Taubman. A sophisticated and passionate art collector himself, he recently got the art-world attention by selling to the Getty, via Sotheby’s and his family trust, the extraordinary Danae that Orazio Gentileschi painted in 1621 for the Genoese patrician Giovanni Antonio Sauli. Politically active in his home town Chicago during the 1970s, Mr. Feigen is also author of Tales from the art crypt, a must-read art book he published at the turn of the new millennium apparently in order to shape a specific mentality, more than just to share his life experience. Since the beginning of his career he has been considering art in all its facets, cultural, political and economical, and he is keeping the door open both to old masters and contemporary art. Today Richard L. Feigen & Co. is probably still the only one gallery which can put side by side old masters such as Bernardo Daddi and Guercino, with Thomas Gainsborough, Paul Cézanne, Henry Rousseau, Max Beckmann, Balthus, Robert Matta, Joseph Cornell, or James Rosenquist. Richard Feigen is also the only main old masters and modern art dealer who was so brave to open in New York a venue dedicated to contemporary art, Feigen Contemporary, that in 1997 was one of the earliest and largest galleries in Chelsea.

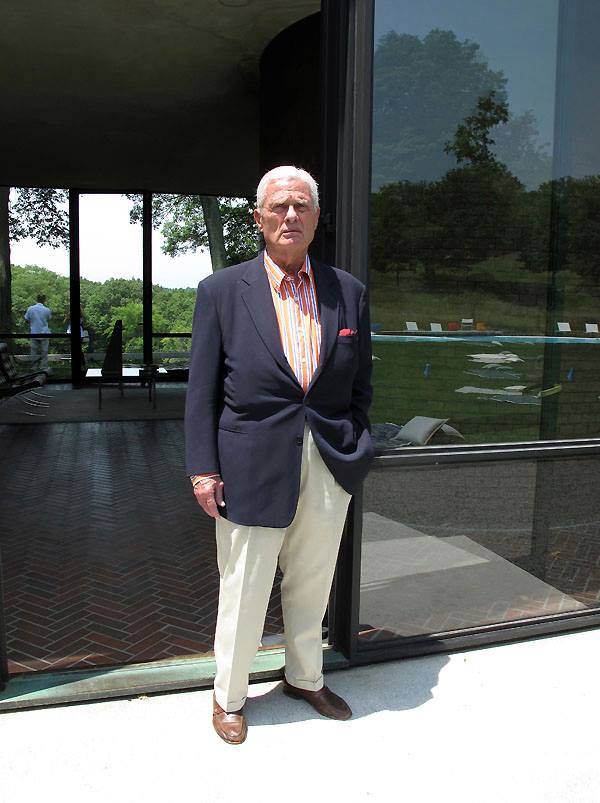

Richard Feigen, courtesy of Paul Laster.

Almost 20 years have passed since you wrote Tales from the art crypt. How did the art-scape changed since then?

Richard Feigen: I don’t think anything has changed.

Do you mean that internet, social networks and powerful auction houses web sites haven’t marked any significant difference?

Richard Feigen: No, not in our business.

So, what advice would you give to a young dealer who is starting to sell art?

Richard Feigen: Well, I’ll ask him which things he’s interested in, because the business is changed dramatically since I started. If he was going into the old masters field I would warn him away from it because this field is just about to dry up. Everything is now focused on the contemporary field.

Do you mean that the base of old masters collectors is somehow vanishing?

Richard Feigen: The collector’s base for old masters paintings is very small now. Museums are appointing directors that are focused on the contemporary area, thus even museums are not good clients any more. We’ve always done a lot of business with them, but they are not doing much now. They are selling out their old masters collections. They are probably a little more active in drawings, but not really as far as paintings and sculpture are concerned.

What do you think about the new policy adopted by the Met with regard to contemporary art?

Richard Feigen: I have doubts that the Metropolitan should be involved in contemporary art. I don’t think you need five museums in one city all competing with each other in the same field. If I were in a position to make policy I wouldn’t put the Metropolitan in the contemporary field. I would leave it to the Whitney, the Guggenheim, or the other museums which have it as their major concern. Nevertheless I think the Met Breuer is a good idea. The former Whitney is a wonderful contemporary building, and it’s great for exhibiting works of art.

What do you think is the reason why, on the contrary, the Met has opened the door to the present?

Richard Feigen: I can only speculate about it. I assume that they think this is where the audience and the market are, and they are following them. But I don’t believe that’s the way a museum should go. A museum should instead lead the audience where it wants it to go.

At the beginning of the chapter dedicated to Julian Levy you wrote in regards with “a breed of man” that, as Levy himself, was educated at Harvard in the humanities and connoisseurship: “They were neither brought up nor educated to make money, which their families had in greater or lesser abundance. They became educators, publishers, museum directors, art collectors and dealers, but also scholars and, above all, gentlemen”. Is today still important to be a gentleman?

Richard Feigen: It doesn’t seem to be any longer a requisite. People like Wright Ludington, Joe Pulitzer, and Julian Levy as well just don’t exist anymore. As museums, today art dealers are not telling the market where it should go. They are simply asking the market where it wants to go now and then they go along. That has not been my policy. I’ve always thought that I would try to educate the market rather than letting it educate me.

What Cfa mostly admires of your approach to art is that since the beginning of your career you have been dealing with art from all the epochs, from Orazio Gentileschi and Max Beckmann to Joseph Cornell and Francis Bacon. Would it still be possible, nowadays, to run a gallery with this same approach?

Richard Feigen: Right now, with the ideas that I have, I don’t think I would go into the art business.

Why not?

Richard Feigen: I don’t think the audience is there, and the problem is creating an audience. In the days when I started there were people, and collectors, that don’t exist any more.

Is it due to a lack of good education?

Richard Feigen: I am not sure, I don’t know how education will change. Harvard no longer has a strong art history department as it had back in the 1920s and early 1930s. I don’t know where anybody would go to get an education in connoisseurship. Such institutions don’t exist today in the United States. On the contrary, and again, education is driven by the market.

As you wrote in the chapter dedicated to the power of the press you stated that “appearing in the press in a purely social context may get you up front at Le Cirque but does nothing for business”, at least your business. Is it still true? Or, to put it in a different way, the most powerful news today is that about the price of the artwork given by the auction houses themselves…

Richard Feigen: That it is largely true. Ray Johnson didn’t get any attention to speak of until he committed suicide dramatically. And then he slipped back into the shadows. The way auction houses capture the press and the audience is very peculiar. I can’t tell now, looking at young artists’ works, which ones are likely to be successful because it doesn’t seem to depend on the quality of what they make. Other extraneous forces are in the wood. It’s much more in the power of the art dealer. That seems to govern the acceptance by the audience and the press. Certain art dealers have the power to commend the attention of the press and therefore their artists are successful, their shows are sold out, and the things get very expensive. So it follows that a work like the Orazio Gentileschi’s that the family trust of mine recently sold is worth less than a Richter’s, an artist that is really questionable. Similarly, Jean-Michel Basquiat, who died at 27, would have brought more money than our Gentileschi’s, that was possibly considered one of the five greatest paintings to come on the market since the World War II.

As a matter of fact, today money are driven by the taste. Your own eyes don’t count that much.

Richard Feigen: No, they don’t. You couldn’t go and look among the works of young artists and guess which one would be successful because it doesn’t depend on how significant the work is. You just can’t tell, it’s impossible. The point is, which gallery is presenting the work. If it’s presented by Gagosian or David Zwirner it’s like a guarantee that he will be successful. But you can’t go out and see which artists are interesting, because you will be wrong.

Do you still look at emerging artists?

Richard Feigen: I don’t have the time to go and visit so many galleries and studios, but we have somebody here working with us who has knowledge about what is going on.

Do you know how many copies of Tales from the art crypt have been sold up to now?

Richard Feigen: When it was published we sold about 16.000 copies. But I have no idea about the on-line sales.

Next Fall the Tefaf is going to open its first US edition at the Armory in New York. Would you like to comment on it?

Richard Feigen: For many years I’ve tried to get the exhibitors of the Tefaf to show in New York, and I think it’s a very good idea. The problem in New York is that there is only one space that is suitable for this purpose, that is the Armory on Park Avenue. But it is too small for all the art dealers who want to exhibit. So they will have a problem in editing the galleries that will show there. Anyway, if they do it right, it could expand the audience for old masters. It could change things dramatically. It could bring some of the hedge-fund guys up to see it, because its location and publicity will commend.

Are hedge funds taking the role once played by museums?

Richard Feigen: We still deal a lot with museums. But some of the young guys who have huge success in the financial market are big collectors of contemporary art and if they can be cut-over to the Armory to look at other things they might change their approach to art collecting. The problem is that they are not acquainted with the old schools of painting and museums haven’t done a good job in educating them. So right now they don’t know where to go and Tefaf could give them a place to look and learn. Tefaf could be a real game changer in terms of the art market.

More in general, what do you think about the growing power of the art fairs?

Richard Feigen: Art fairs are not making the market, they are following it. The most important factor in making the art market has been the auction houses. Contemporary fairs do very well because people get their education of the art market mainly from the auctions and basically from the prices that are commended at auctions.

Which are in your opinion the top three influential museums today? And who are the top three museum directors?

Richard Feigen: It’s a very hard questions. I don’t think that the Museum of Modern Art is that powerful any more, nor the Guggenheim, the Whitney, the Metropolitan, the Art Institute of Chicago. When I started the business there were three or four very influential museum directors. They are not there any more. And neither the places that trained them. The reasons for choosing a museum director are different.

Why do you think these institutions, like the Centre Pompidou or the Tate, are not influential as they used to be?

Richard Feigen: All the fields are driven by the market. Right now none is doing anything very adventuresome. There is no museum’s venue that could change the attitude towards an emerging artist. They simply do things that have been done before. So it follows for museum directors.

December 2, 2019