Giorgione at the Royal Academy of Arts in London is so contemporary, contemporary, contemporary…

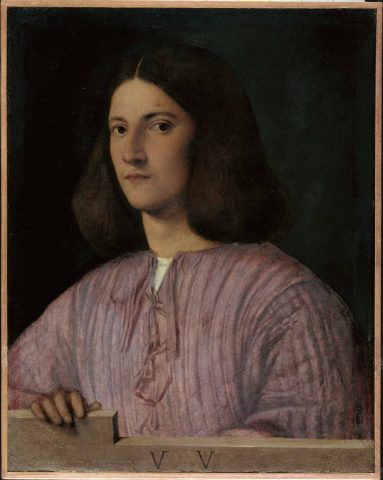

- Giorgione, Portrait of a Young Man,(‘Giustiniani Portrait’); oil on canvas, 57.5 x 45.5 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz Photo © Jörg P. Anders.

- Giorgione, Il Tramonto, (The Sunset); oil on canvas, 73.3 x 91.4 cm. The National Gallery, London, photo © The National Gallery, London.

- Titian, Two Arcadian Musicians in a Landscape; pen and brown ink over black chalk on paper, 22.4 x 22.6 cm. On loan from the British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum.

- Attributed to Sebastiano del Piombo, Portrait of Francesco Maria della Rovere; Oil on panel (transferred to canvas), 73 x 64 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna Photo © KHM-Museumsverband.

ROSALIND: Why then, can one desire too much of a good thing?

Come, sister, you shall be the priest and marry us.

Give me your hand, Orlando. What do you say, sister?

From – ‘As You Like It’, William Shakespeare, 1600.

There are some paintings that demand re-visiting, as there is so much to take in and to discover. This might be a frustrating, but acceptable, aspect of temporary exhibitions – but there are paintings that can endure a lifetime of revisits, to review and understand afresh as one gets older. Giorgione’s, ‘La Vecchia’, [c.1508-10], which usually resides in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, fits the bill, literally, as the enduring pathos of the elderly woman’s presence, arguably approaching the achievements of Rembrandt in portraiture, testifies. And here she is, in London.

A show organised around a handful of works by a barely, and not even reliably, documented artist from Venice 500 years ago might sound curious, but this fascinating exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London demonstrates that the paintings of Giorgione da Castelfranco and his contemporaries in Venice provided a catalyst for portraiture and landscape painting for the next half-millennium.

The exhibition occupies five galleries and presents 46 works – 39 paintings, augmented by six drawings and a Tullio Lombardo, marble, double portrait bust (‘Bacchus and Ariadne’, [c.1510] – or perhaps a decade later). Counting the number of works on display might appear unnecessary, but such a relatively small number of artworks more than amply represents the historically noteworthy shift in painting at the start of the Cinquecento.

History of Art scholar, Donal Cooper, writing for the May 2016 issue of Apollo magazine, poses the question – “Are there too many Renaissance exhibitions?” as the title of his thought provoking discussion on the current spate of Italian Renaissance art exhibitions. That the ‘great masters’ remain so popular, and subject to appropriation (see ‘Botticelli Reimagined’ at the V&A), cannot be denied. However, to Cooper’s question one might counter: “But can you have too much of a good thing?”

Indeed, the ongoing interest in the Renaissance (not forgetting the Northern tradition) might reveal something about culture today rather than the past. The constant and programmatically necessary changes in Modernism and Post-Modernism might be a factor in sending the art fans back to the past for certitude and constancy in the visual arts. But this belief would be mistaken, for the decade in which these paintings were produced by Giorgione and his contemporaries represent significant changes in the pictorial language, purpose and status of painting. Just as Florence, and then Rome, had been the great centres of artistic development in southern Europe in the preceding decades, the Venetian Renaissance is suitably represented by this impressive selection presented in the Sackler Wing of the RA.

‘In The Age of Giorgione’ reveals portraiture continuing (though not starting) the development from the representation of ‘type’ and the impersonal to a more individuated sense of personhood and self – even before the Enlightenment. This is achieved through an ever-evolving sophistication in the skilful handling of oil paint, recording an awareness of the visual power of light and dark aligned to gesture, form and narrative. The portraiture that opens and dominates this exhibition demonstrates the shift from the figure typically looking away (e.g. Giovanni Bellini’s, black capped, ‘Portrait of a Man [Pietro Bembo?]’, of c.1505); or Albrecht Dürer’s, ‘Portrait of Burkhard of Speyer’, [c.1506] (a veritable Van Morrison lookalike) who, lost in thought, might suddenly look around and ask the onlooker a question; and then the intent look is directed at the viewer, as for example in Dürer’s, ‘Portrait of a Man’, [1506], who’s eyes glisten, on the verge of tears perhaps, and palpably suggest the notion of thought and consciousness; and then back again to the theatrical pose in, ‘Portrait of a Young Man [Antonio Brocardo?]’ [1503 or 1510] by Giorgione, that expresses classically inspired and poetic subject matter rather than biblical content – and essentially denoting the cultural sophistication of the owner of the painting with unequivocal inference.

We also see signs of the burgeoning art of the landscape as sole subject matter, changing from backdrop (possibly a criticism of Giorgione’s ‘Trial of Moses’ of c.1496-9) to all engulfing environment, as in Lorenzo Lotto’s ‘Saint Jerome’ of 150[6?], creating an atmosphere so powerful and animated that it barely needs the inclusion of the Saint or his lion to communicate to the viewer the physical and psychological demands of the penitential act – as most connoisseurs at the time, and as viewers now, could only derive from the imagination with the assistance of an image such as this.

In Giorgione’s, ‘Il Tramonto [The Sunset]’ [c.1502-05], loaned from the National Gallery in London, the dominating spindly tree is placed at the centre of the scene – exactly where it should not be placed in a composition if aesthetic rules are to be followed. But rules were still being invented at this time, and the tree acts as the central visual hub around which the predominant subject matter revolves. Part of the enigma of Giorgione is that we do not actually know what the subject matter is in many of the works attributed to him, which allows for restorers of the past to go a bit crazy. George and the Dragon, almost foregrounded on the right hand side of the composition, were such additions. Nor is this a landscape with saints – a ploy that enabled the introduction of the landscape genre. The almost insignificant ‘monster’ in the bottom right was added too. So it seems quite a surprise that the two main figures, and the more centrally placed animal form, are original. Giorgione’s proto-achievements with landscape lead, ultimately, to Claude, via Titian. His landscapes of the imagination (yet tied to conceptions of Arcadia and the Pastoral) perhaps lead, via Poussin, to Dali. So, in this sense, the exhibition we think that we are viewing is much greater than the sum of its parts.

In the penultimate gallery, titled the Devotional Works section, Giovanni Bellini’s sacra conversazione, ‘Virgin and Child with Saint Peter and Saint Mark and a Donor [‘Cornbury Park Altarpiece’]’, [1505] hits the visitor with the force of a Hans Hoffman abstract painting, if only for the bold colour-shapes that creates the first, memorable and opulent, impression. On closer inspection, as our RA guide explained, we probably see the work of Bellini and his workshop assistants. The format is northern (for the greatest painters are links in a chain, after all) and the conversational relationship is between the Madonna and the Saints. On the human level, the viewer can identify with the purple-cloaked donor, who might represent us mere mortals, although he is a bit cardboard-cut-out flat in a stylistically dated profile. However, in Giorgione’s ‘Virgin and Child [‘Tallard Madonna’], [c.1500-05], the viewer has a more direct visual and emotional relationship with the distracted child and His Mother. As she is absorbed in her book, we are equally immersed into the image – painting is becoming personal.

Involving the viewer psychologically is both seen and experienced in Titian’s, ‘Christ and the Adulteress’, [c.1511], which, if attributed and dated correctly, was painted by the artist in his early 20s. It’s a simple but effective composition. The darkness of the shadowy figure on the left of the picture, with his back to the audience (us) connects in chiaroscuro richness to Christ who is highlighted by a light source, also from the left hand side, in the centre of the arrangement. His arm points, in effect, to a contemporary Venetian (dressed in a beautifully rendered yellow/orange tunic), who in turn presents the ‘Adulteress’ to Christ. Missing, except for a knee, but worth mentioning, is the final major character in this row of figures, as on the far right hand side, the figure of a man looking directly at the onlooker should be there. Fortunately, a small reproduction of the most essential of the missing sections (Titian’s imaginatively titled, ‘The Head of a Man’, also in the Glasgow Museums collection) is reproduced next to the painting. The rather dandy looking young man strikes a contraposto pose and looks intently at us – “Will you cast the first stone?”, he may be asking – and we might hide our faces into the shadows in response. Morality is implied heavily – but in the visual pleasure of a zigzagging row of slanting heads, where stilled but revolving figures appear to injudiciously dance in a subtly off-kilter landscape space, Jesus levitates, and the near black left hand block of negated colour contrasts with the pastoral background. Beware of darkness.

Also in this room is Titian’s, ‘Virgin and Child [‘Lochis Madonna’], a nativity scene from c.1511. The subject is nothing new but, at a diminutive 38x47cm, this small oil on panel is as breathtaking and masterful in its colour-relationships as any painting of greater dimensions. Normally you would have to travel to Italy to see this painting – and if that journey were to be made on foot, walking from London to the Accademia Carrara di Belle Arti di Bergamo, would be worth it. This is an absolutely joyous painting. The chubby baby is held adoringly by His Mother; who’s red and blue robes add a vibrant richness next to the flesh tones of both her head and the gesticulating infant. This literal triangulation of the foreground colour arrangement is set against a predominantly earthy green middle distance and a watercolour-like, exaggerated, fizzing blue, aerial perspective, backdrop. It adds up to a visual amplification and expression that Emile Nolde would have been proud of.

So, is this too much of a ‘good thing’? Quality is quality, after all. What might be seen as reactionary or dated, may actually affirm that tradition informs the present and is inevitably behind whatever unfolds and develops into the future. In Renaissance art, for better or worse, humankind takes centre stage. ‘In the Age of Giorgione’ confirms the developments and potential of the preceding Quattrocento in its unique Venetian context in the first decade of the following century. Then, and now, individuals, communities and cultures remain at the centre of attention, both against the backdrop of, and in, the natural environment. Our relationships with each other, and with nature, have never been so significant.

As the actors were repeating in that Tino Sehgal’s performance, this is so contemporary, contemporary, contemporary…

JACQUE: “All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players”

From – ‘As You Like It’, William Shakespeare, 1600.

November 25, 2020