Interview: Malta Campos, one of the only 3 painters invited at the SP Biennial (out of 87 artists!)

- Antonio Malta Campos, Untitled, 1996; oil on canvas, 180 x 180 cm. Private collection, São Paulo Courtesy Galeria Leme.

- Antonio Malta Campos, Fóssil, 2013; acrylic on canvas 180 x 200 cm. Collection of the artist, São Paulo Courtesy Galeria Leme.

- Antonio Malta Campos, Capacete, 2015; oil on canvas, 230 x 360 cm. Assistant: Antonia Baudouin.

- Antonio Malta Campos, Dimensão, 2016; oil on canvas, 230 x 360 cm. Assistant: Antonia Baudouin.

- View of Antonio Malta Campos’ paintings at the 32nd São Paulo Biennial. Photo Antonio Malta Campos.

- Antonio Malta Campos, Mapa Mundi, 2015; oil on canvas, 230 x 360 cm. Assistant: Antonia Baudouin.

- Antonio Malta Campos, SIM NÃO, 2015; oil on canvas, 230 x 360 cm. Assistant: Antonia Baudouin.

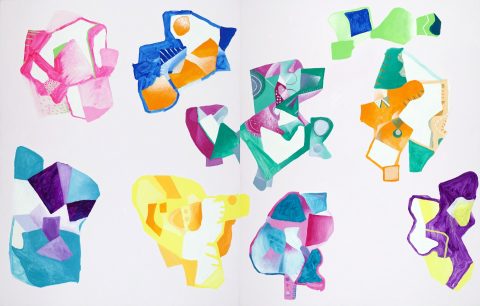

- Antonio Malta Campos, Misturinha, 2015. Photo Antonio Malta Campos.

- Antonio Malta Campos, Misturinha, 2003. Photo Antonio Malta Campos.

- Antonio Malta Campos, Misturinha, 2003. Photo Antonio Malta Campos.

Antonio Malta Campos (São Paulo, 1961, where he lives and works) started to produce oil paintings soon after being accepted at the Universidade de São Paulo (USP), in 1980. Like many artists of his generation, Malta Campos was involved in what has been called, in Brazil, the 1980s ‘return to painting’ — a shift of interest among artists, after decades of avant-garde experimentation. Having left the Casa 7 studio in the beginning of 1983, Malta Campos did not take part in the 1985 São Paulo Biennial, which emphasised the current painting trend. In the 1990s, Malta Campos obtained a degree in Architecture from USP and, being already a father, started to work as an architect to support himself. The artist resumed his artistic career in the late 1990s, and since then his work has gained prominence in an increasingly internationalised Brazilian art scene. The artist is present at the 32nd São Paulo Biennial, which opened on 6 September amid great political turmoil in Brazil. One week before the opening, president Dilma Roussef had been impeached; the artistic community, predominantly against her impeachment, took the opening as an opportunity to register their frustration: several of the participating artists wore T-Shirts reading ‘Diretas Já’ (‘Elections now’, a motto borrowed from the re-democratisation process of Brazil in the 1980s) and ‘Fora Temer’ (‘Temer out’, Temer being the vice who became president). Noteworthy, the biennial’s title is Live Uncertainty.

Most of the works presented at this edition are site-specific projects which, in its majority, will only exist throughout the duration of the biennial. The curators have been largely criticised – mainly by an older generation of critics such as Aracy Amaral and Rodrigo Naves – for what has been perceived as an absence of ‘genuine’ art. Here, Conceptual Fine Arts presents an interview with Malta Campos, who is one among the only three painters – out of 87 artists and collectives – whose works are on show.

Can you please tell us what are the works that you’re showing at the 32nd Sao Paulo biennial?

I am exhibiting two bodies of work. The first body of work consists of four large oil on canvas diptychs, all measuring 230 x 360 cm. Three of the diptychs are from 2015 and one is from 2016. All of them (and some more) were made with the help of my young and talented assistant, Antonia Baudouin, who is actually a cinema student and a movie director, but nevertheless an excellent painter (daughter of my friend, the painter Rodrigo Andrade). I mention my assistant because the paintings are really a collaboration between me and her, with creative decisions being made by the two of us. Our work together can be seen in the sequence of photographs, edited as videos by Antonia. The second body of work — the Misturinhas (Little Mixtures) — consists of 249 little paintings, drawings and collages on paperboard (each measuring 25 x 20 cm), made in the last 15 years. They are mounted as an installation in the walls of the biennial, in chronological sequence. The first Misturinhas are from 2000, the last ones from 2015, and they didn’t have the help of an assistant — although, now, I am starting to make new ones with Antonia’s help…

The idea of producing — repeatedly, year after year — various works over the same shaped paperboard surface is fascinating. Can you tell us a bit more about the Misturinhas?

When I started to make them, in 2000, it was an act of defiance. Back then, I was making large abstract expressionist paintings — my “official” work. With the large paintings, I was trying to be accepted in an art scene that praised this kind of formalism (things changed since then…). But I was bored. The Misturinhas started as a side project: little and cheap works in paperboard, in defiance of the strict modernist rules I was adhering to in my large paintings. So, from the start, there was an ‘anything goes’ attitude towards the Misturinhas. They could have figures. They could be abstract. They could be modernist. They could be academic. They could be very bad, stupid little works. They could be really good little gems. They could have collages, in a cubist spirit. And they started to acquire a personal tone, at least for me. I started to write things on them: lyrics from songs I would hear, at random, in the studio. At some point, my daughter Antonia Malta, a teenager and high-school student at the time, gave me her nail polish set and her childhood sticker collection. I started to make Misturinhas with them. In 2003, when I already had made more then a hundred Misturinhas, I started to date Kika, to whom I am married now. Kika and my daughter immediately got on with each other, and they decided, somewhat against my judgment, that the Misturinhas were the best thing I had ever done. Since them, I never stopped doing these little works.

How do these works — and your practice in general — relate to ideas of ‘uncertainty’ and ‘entropy’ that are the driving forces behind this edition of the Biennial?

I have been asking myself this question since Julia Rebouças and Jochen Volz visited my studio earlier this year, to see my work and eventually invite me to the biennial (which they did). I guess there is a good deal of uncertainty permeating my work, and I have a feeling the curators sensed this right away. The first and most basic of my uncertainties has to do with the contemporary practice of painting. Painting, as a historic medium, presented us with images that told stories. Modernism challenged this, but painters payed a high price for that challenge. Painting is no longer the main image medium of the world: photography, video, and cinema are. Painting sidestepped into oblivion. Or has it? To make a painting today is to ask this question. Other uncertainties that I have can be found in the work itself. I tend to suspend every meaning, in the process of making a picture. In other words, I don’t take into account the usual meaning attached to the figures and forms that I use. This can be best seen in the Misturinhas. Equally important, my process of creating paintings, letting things just happen, is a process permeated with uncertainty from the beginning. Antonia, my assistant, understands this process very well: she knows that every painting is an adventure into the unknown. This method can bring the work near to chaos, and that relates to entropy, a measure of the disorder of a system.

There is a recurring figure in your canvases, a diamond-like — though often barely figurative — shape, that at times resembles a head, at times a territory in a map, and at others is purely abstract. Can you tell us a bit about this image?

The very first painting on canvas that I did, in 1980 or so, after years of drawing on paper, was a painting of a head. A kind of imagined portrait of someone, with abstract forms — with little realism. The reason for this is that I didn’t have any idea of what to paint — I was interested in how to paint, but I didn’t have any story or theme to work on. That was my first crisis — to paint a figure that signifies nothing. The recurring figure in my ‘head’ paintings is exactly this senseless head that represents an invented character, someone that stands there for nothing. I think the only interest of this figure is how it is constructed. A number of my paintings, mainly the ones that I do in ‘portrait’ shaped canvas, start with this vague figure, a figure that can be painted anyway I want, and still be a figure, by definition. Sometimes, the paintings end up as an abstraction. But looking at it, I know that it is a head. Sometimes, people get surprised when I tell them about the ‘head’ they are looking at. They see other things. When this happens, I remember that Picasso never endorsed abstraction. He said that an abstract picture can be anything in the eyes of the viewer. And that is not good… for the painter must enforce his view to the public.

Who – or which — are your strongest influences?

Cubism is very interesting: forms and figures are used to represent things in a way that challenges the main rule of western painting — mimesis. Picasso is obviously the case in point here, but I like to study Modernism as a whole, including Brazilian Modernism. I would also like to mention the artists that I know personally, in São Paulo. Working, from the beginning of the 1980s, along my Casa 7 friends (or against them, later, when I left the studio), was, in fact, my art school. The Casa 7 artists: Rodrigo Andrade, Carlito Carvalhosa, Fábio Miguez, Paulo Monteiro and Nuno Ramos. After this, in the late 90s, I met artists of a newer generation, artists that made me view and think my work in a broader context. I am thinking in particular of my dear and talented friend Erika Verzutti — she made me see my own awkwardness in a more positive way. And, in recent years, a new generation of painters or image ridden artists have emerged in Brazil. Some are oil painters, like Bruno Dunley, Ana Prata and Álvaro Seixas, and some, like Sofia Borges, work with digitally manipulated photographs, presenting their work like painters do, with big images hanging on the wall. All of them are my close friends and I am influenced by them, all the time.

You have been active for several years, yet this is your first Biennial. In your view, how does participating in such an important exhibition impacts the career of an artist?

Most artists of my generation (I was born in 1961) have already showed their work at the São Paulo Biennial, the international art show mounted every two years in my home town, since the 1950s. I never have, until now. There are a number of reasons for this. I missed the 1985 Grande Tela (The Great Canvas) edition, maybe because I was no longer part of the Casa 7 studio (my friends from Casa 7 were all part of the 1985 Biennial, invited by curator Sheila Leirner). Then, in the 1990s, I worked mostly as an architect. Between 2000 and 2007, I showed my paintings, and the Misturinhas, in alternative and small art galleries in São Paulo, but few people, beside artists and friends, took notice. In 2012, things started to change. That year, curator José Augusto Ribeiro mounted a big show with my paintings and Erika Verzutti’s sculptures, at the Centro Cultural São Paulo. Called Antonio Malta e Erika Verzutti, that exhibition introduced my work to a much broader audience, in Brazil and abroad (there was an international attendance because of the São Paulo art fair happening at the time). Important collectors in Brazil bought my work, and in 2014 I took part in the Saatchi Gallery survey Pangaea: New Art from Africa and Latin America, in London. I guess my participation in this present edition of the São Paulo biennial results from the recent visibility my work has acquired. But it goes beyond that, I think. It means that my doubts and uncertainties are not only mine, but everyone’s. I am indebted to the curators, in particular Jochen and Julia, for helping me understand that my work has a universal appeal.

October 4, 2016