Kerry James Marshall: ‘I love art thanks to Leonardo da Vinci’ (an interview)

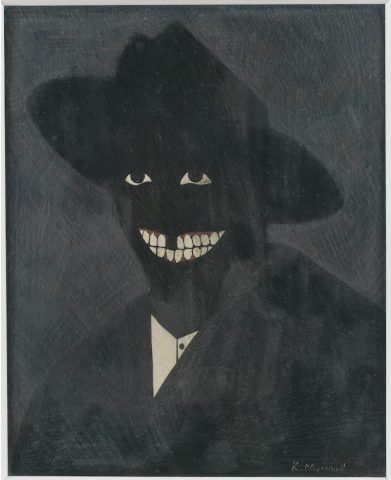

- Kerry James Marshall, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self 1980 Egg tempera on paper 8 × 6 1/2 in. (20.3 × 16.5 cm) Collection of Steven and Deborah Lebowitz © Kerry James Marshall Photo: Matthew Fried, © MCA Chicago.

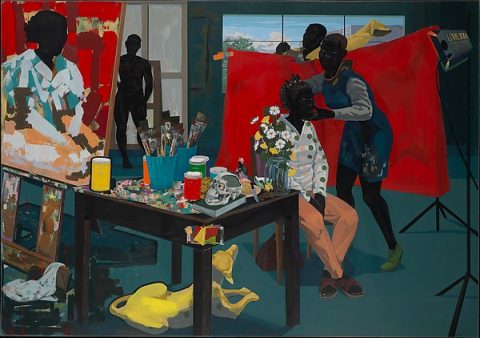

- Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Studio), 2014 Acrylic on PVC panels; 83 5/16 × 119 1/4 in . (211.6 × 302.9 cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Foundation Gift, Acquisitions Fund and The Metropolitan Museum of Art Multicultural Audience Development Initiative © Kerry James Marshall.

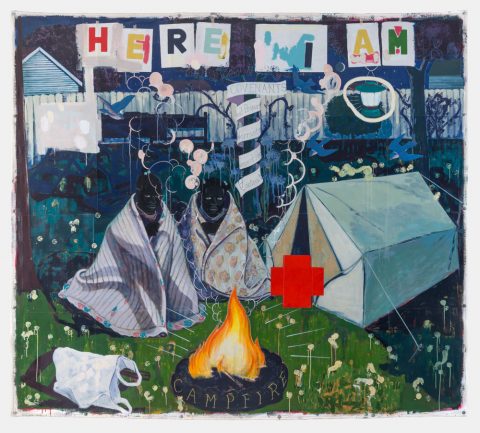

- Kerry James Marshall, Campfire Girls 1995 Acrylic and collage on canvas 8 ft. 7 in. × 9 ft. 6 in. (261.6 × 289.6 cm) Collection of Dick and Gloria Anderson © Kerry James Marshall Kerry James Marshall Photo: E. G. Schempf.

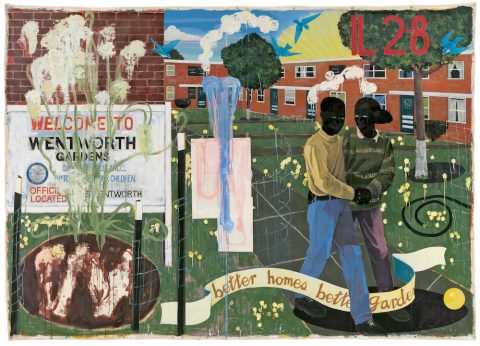

- Kerry James Marshall, Better Homes, Better Gardens 1994 Acrylic and collage on canvas 8 ft. 4 in. × 11 ft. 10 in. (254 × 360.7 cm) Denver Art Museum © Kerry James Marshall Photo: courtesy Denver Art Museum.

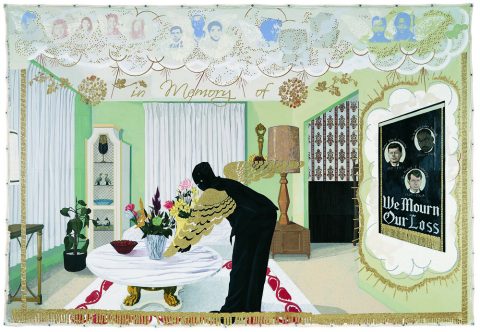

- Kerry James Marshall, Souvenir I, 1997; acrylic, collage, silkscreen, and glitter on canvas 9 × 13 ft. (274.3 × 396.2 cm) Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Bernice and Kenneth Newberger Fund, © Kerry James Marshall Photo: Joe Ziolkowski, © MCA Chicago.

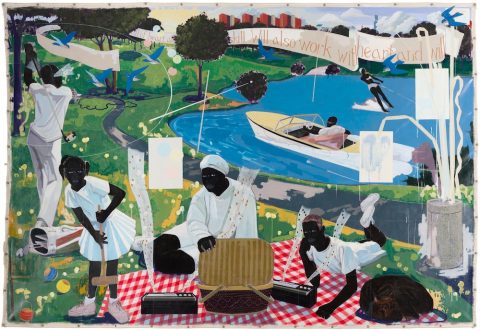

- Kerry James Marshall, Past Times 1997 Acrylic and collage on canvas 9 ft. 6 in. × 13 ft. (289.6 × 396.2 cm) Metropolitan Pier and Exhibition Authority, McCormick Place Art Collection, Chicago © Kerry James Marshall Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

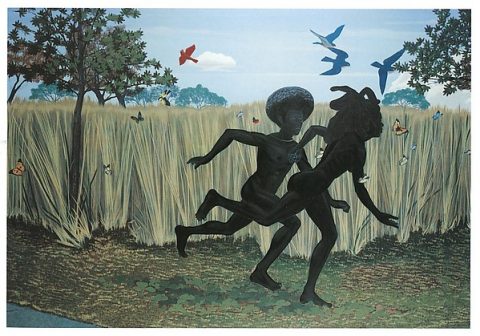

- Kerry James Marshall, Vignette, 2003; acrylic on fiberglass 72 in. × 9 ft. (182.9 × 274.3 cm) Defares Collection © Kerry James Marshall.

- Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Painter) 2009 Acrylic on PVC panel 44 5/8 × 43 1/8 × 3 7/8 in. (113.3 × 109.5 × 9.8 cm) Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Katherine S. Schamberg by exchange, 2009.15 © Kerry James Marshall Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

- Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Workshop, Odalisque in Grisaille, oil on canvas 32 3/4 x 43 in. (83.2 x 109.2 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1938 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Willem de Kooning, New York Woman; oil and charcoal on canvas 45 7/8 × 31 3/4 in. (116.5 × 80.6 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, From the Collection of Thomas B. Hess, Gift of the heirs of Thomas B. Hess, 1984 © 2016 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Growing up in Los Angeles during the turbulent times of racial unrest in the 1960s and settling in Chicago in the late-‘80s, Kerry James Marshall is celebrated for creating a place for the representation of black people within the canon of Western painting. The subject of the largest museum retrospective of the work of an American artist in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s history, Marshall recently spoke with Conceptual Fine Arts by phone from his Chicago studio to discuss the scope of his exhibition, “Mastry”.

The earliest work in the show, “A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self,” depicts a shadowy figure that’s mostly visible by the white of his eyes, teeth and shirt. What did he represent when you made this painting in 1980?

Kerry James Marshall: I look at that picture as a kind of reset, a return to zero. I had come to the conclusion that the kind of work that I was previously doing—mixed media, abstract collage and assemblage—wasn’t going to get me where I wanted to go. It didn’t address the lack of black figures in what might be called the pantheon of important art works.

The shadowy figure, or a variation of him, reappears in your 1986 canvas “Invisible Man.” Is this painting inspired by Ralph Ellison’s famous novel with the same title?

Kerry James Marshall: The prologue of Ellison’s book had a huge impact on the conception of that figure and the idea of invisibility. That’s where I really understood the distinction between the two different qualities of invisibility—one being more social and psychological and the other being physiological. It struck me that you could have presence and absence in a work at the same time, which was something that I was trying to achieve in that painting.

Does literature play a big part in your art?

Kerry James Marshall: Well, that black figure is an image that has been recurring in a lot of literature—everything thing from Richard Wright’s “Native Son” to Toni Morrison’s “Beloved.” There are descriptions of this extreme condition of blackness in the book “Twelve Years a Slave,” which the movie was based upon.

Do you only paint black figures?

Kerry James Marshall: It’s not like I never paint anything without black figures, but in quantitative terms it’s probably the thing that you are least likely to see when you go to an art museum. The whole history of art is built on the idea of representation and most of those figures are white. You are never going to achieve a level of equality unless the black body exists in representation at the same level and in some ways at the same quantity—with the same levels of complexity, sophistication and aesthetic value. If you don’t find those things in paintings you will never believe that they belong in paintings.

I’ve read that you have a love of the Old Masters. How have their art influenced you?

Kerry James Marshall: The first thing that you learn about in art history is Leonardo di Vinci and Michelangelo. My love of art making came from seeing books about the Old Masters in the library and going on field trips to museums, where you saw more of it but in real life. At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art my favourite paintings were two big Veronese canvases of muscular male figures that looked like superheroes. Over time, my interest gravitated toward the Flemish painters, who had a style of clarity and crispness that appealed to me. The Florentine fresco painters also interested me because their work required both knowledge and precision. (Here is a link to our writing about the role played by restorer Dianne Dwyer Modestini in saving the troubled Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci).

You’ve also been inspired by comic books, particularly in your on-going “Rhythm Mastr” series. What do you find intriguing about comics and how do you use them?

Kerry James Marshall: The overarching concern for a lot of my work has been this absence of competitive equality. As a child when you look at comic books and superheroes you start to realise that most of the superheroes that you admire are white guys. At some point it begins to be unacceptable. Rather than depending on someone else to create these images, you have to take matters into your own hands. The “Rhythm Mastr” work allows me to get into the competitive arena and project an ideal image of the black body into the world. It’s my way of telling black youths that you can be inventive, too.

Your “Garden Project” paintings use the names of housing projects as the point of departure and one of them includes a sign for Nickerson Gardens in Watts, where you once lived. How did growing up in that Los Angeles neighbourhood during turbulent times impact your life and art?

Kerry James Marshall: The period definitely had an impact on my work. There were things that I saw that had a profound effect on what I thought would be important to do later on as an artist. The history of art making is filled with narrative art that tells a story or documents an event. The Watts Riot, the LAPD raid on the Black Panthers’ Headquarters and the Black Student Union protests were important events that were bound to inspire art.

How important is storytelling to your process?

Kerry James Marshall: I’m less interested in storytelling than I am in staging scenarios. That’s as close to narrative I think I can get. I like to put people in situations in which you can speculate about the possible outcomes. There are assumptions you can make and narratives that you can construct simply by their presence there.

One of the most recent works in the show is the big 2014 painting Untitled (Studio), an epic canvas that combines portraiture, still life and landscape while also utilising both realism and abstraction. What’s the story-line and source of inspiration for this monumental work?

Kerry James Marshall: It’s really about who paints—who paints on a heroic scale. It’s based, in part, on Gustave Courbet’s painting “The Painter’s Studio,” which is part of a whole history of paintings of artists studios, a place where images originate. My canvas shows a woman in the studio painting a model. It shows that she’s the orchestrator; she makes all of the stuff in the painting. The idea is that I paint. I do this, too.

Besides exhibiting your retrospective, the Met has also asked you to select works from the collection that are touchstones by others for you. Were there any works that stopped you in your tracks in that process of looking?

Kerry James Marshall: Actually, I asked the Met if I could make the selection. It was quite difficult to do because there are a lot of artworks in the collection that cannot be moved. One that I did get is an Ingres painting, “Odalisque in Grisaille,” that’s very important to me. There are levels of precision in the painting that make it seem magical. That painting has had a profound effect on my work.

November 25, 2020