Caravaggio’s fossils: science and unsuspected details

In occasion of the artist current exhibition at Palazzo Reale in Milan here some pivotal scientific discoveries concerning Caravaggio’s Maltese Knight.

- Fig. 1, Caravaggio, Portrait of a Maltese Knight, 1608. Oil on canvas, 118,5 x 95 cm.

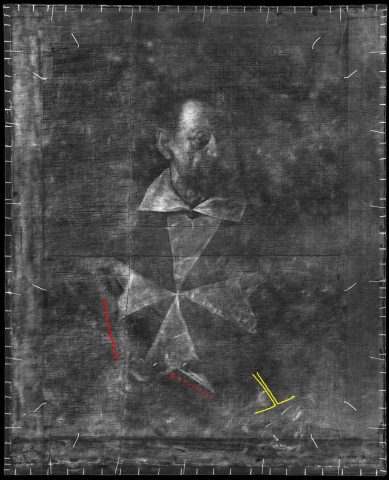

- Fig. 2, Caravaggio, Portrait of a Maltese Knight , X-rays radiography.

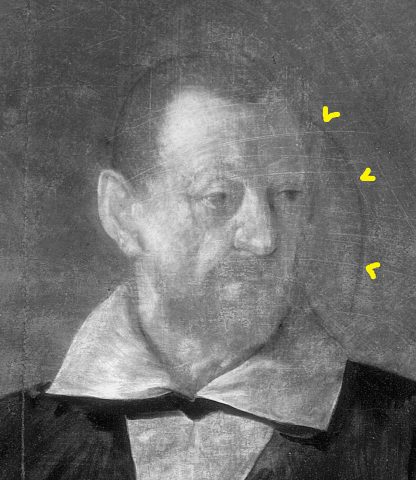

- Fig. 3, Caravaggio, Portrait of a Maltese Knight, IR reflectography .

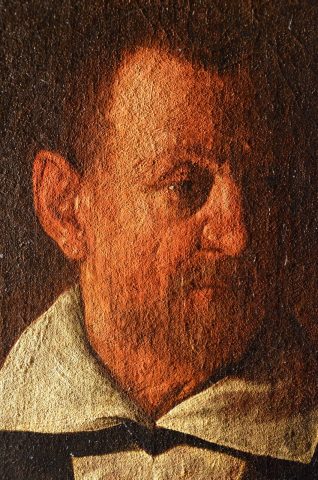

- Fig. 4, Caravaggio, Portrait of a Maltese Knight, detail.

- Fig. 5, Caravaggio, Portrait of a Maltese Knight, detail in raking light.

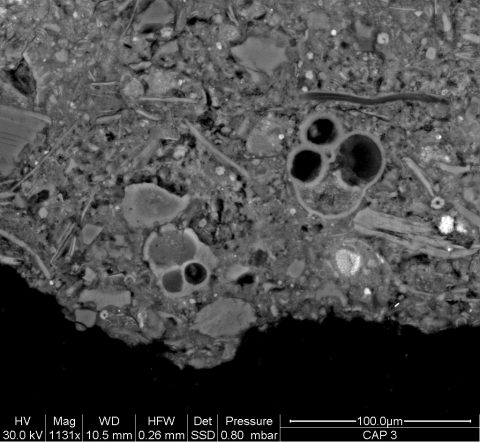

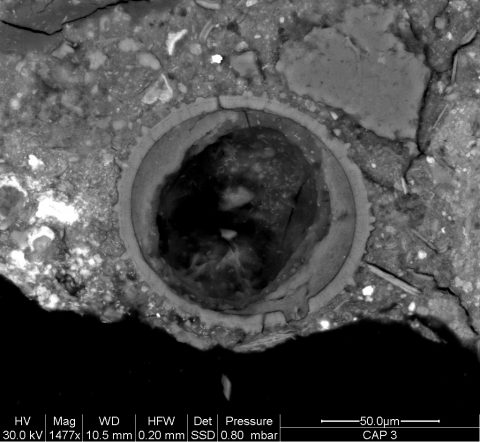

- Fig. 6, Caravaggio, Portrait of a Maltese Knight, cross section.

- Globigerina bulloides

- Orbulina universa d’Orbigny

Before being expelled from the Knights of Malta, on charges of being foul and rotten – “putridum et foetidum”, a way of basically expressing inner corruption, Michelangelo Merisi known as Caravaggio painted some important works for the Knights of Malta, thus gaining his induction into the Order, on 14th July 1608. Among this group of paintings there is Portrait of the Maltese Knight, that is part of the exhibition “Dentro Caravaggio”, currently at Palazzo Reale in Milan, together with other nineteen works by the artist.

Despite the year he spent in Malta between 1607 and 1608 was only in part a quiet time, which indeed ended with a brawl and a subsequent escape, the artist did manage to depict some intense portraits, like the Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt with his Page (Paris, Louvre) and the Portrait of a Maltese Knight (Florence, Palazzo Pitti, fig. 1), generally identified with the Maltese knight Antonio Martelli, or with the Grand Master of the Order of Malta Alof de Wignacour.

In Malta, in slightly more than a couple of months, Caravaggio also painted a striking St Jerome, as well as his largest canvas (3,6 × 5,2 m), The Beheading of St John the Baptist (Malta, La Valletta). This latter is also the only work he ever signed, where his signature “f. Michelang(elo)”, “F” standing for Fra (brother), blends in with the blood from St. John’s throat – autobiographic symbol of a life marked by blood and an intense warning of tragedy.

The scientific analysis which have been duly carried out in the past few years together with the restoration and the study of Caravaggio’s work allowed to deeply comprehend his working method and his evolution, from the attentive observation of Sixteenth-Century Venetian and Lombard painting to the acquisition of a technical, and not just stylistic, personal language. Caravaggio systematically uses dark grounds (brown or red-brown) to highlight the role of light through the contrast between light and dark; but also to paint in a faster manner, thus taking a direct advantage of the background for the shades, leaving it in view in order to avoid complex passages of chiaroscuro, or reducing them with great technical wisdom to the essential.

Painting on dark bases makes the use of preparatory drawings, which generally define the outline of the figures, the structure of the composition and the creases of the clothing, less effective for the mark turns out to be less contrasted; perhaps this is also the reason why the painter makes very little use of drawing, often, albeit not always, replacing it with thin incisions which helped him to position the figures in his “scene”, and reposition the models in the studio. While the use of incisions in colour or in the preparatory sketches has been known for some time, the occasional presence of underlying drawing has been revealed only few years ago thanks to the evolution of the systems employed for infrared reflectography, granting better resolutions and higher penetration of IR radiation inside the painting layers.

When working on dark grounds, also lighter drawing media can be used, and Caravaggio sometimes works directly with pale or white colours (lead white) to sketch the figures (“abbozzi”).

The use of only one, or at most two incisions, as suggested by X-rays radiography (see red solid and dotted lines in fig. 2), and of minimal graphic sketches for some face’s contours as emerged with IR reflectography (fig. 3) is indeed what I discovered when examining the Portrait of a Maltese Knight during the restoration carried out by Anna Monti which took place two years ago under the direction of Fausta Navarro at Palazzo Pitti. Although the work seems to have been largely painted “alla prima” (wet-on-wet), we can spot a few afterthoughts along the outlines of the body and in the sword’s hilt, which was initially sketched a little higher and with a simple cross shape (see yellow lines in fig. 2) by using a pale colour containing lead (lead white or lead-based yellow).

For most part of his career – with the exception of some particularly complex or innovative pieces- Caravaggio paints with self-confidence and has very clear ideas in mind, as proved by the very few changes.

In the Maltese Knights he masterfully uses the dark ground for the shades of the flesh and of the white cross, this latter depicted with few firm strokes of lead white to create silken effects. The hands look unfinished, while the shades and semi-shades of the face (fig. 4) are created “by substraction”, thus taking advantage of the lower layers. The granular surface preparation, almost experimental, is also a specific characteristic of this painting which can be noticed very well in raking light or at close distance (fig. 5).

The cross sections obtained on three samples (by Maria Letizia Amadori, University of Urbino) testified a complex three-layer structure for the ground (fig. 6): a first lighter brown layer, then a darker brown one covered by a dark red one. Overall about 0,6 mm, a thick ground, containing in different ratios red and brown earth, haematite, carbon black and bone black, lead white but also calcite, vermilion red and minium, green as well as unusual red copper-based pigments (cuprite and chalcopyrite). Micas and titanium oxide impurities suggest the use of sand (river sand?), thus explaining the so-peculiar rough surface.

Among the most interesting results, we found out that some calcite particles derived from living organisms: they are microfossils like Globigerina bulloides (fig. 7) and Orbulina universa d’Orbigny (fig. 8) belonging to foraminifera.

The presence of specific fossils could possibly represent a provenance marker from areas which are rich of known fossils, for not documented works. Remains of fossils in the preparation have recently been found also in The Raising of Lazarus (Messina, Museo Regionale) and, above all, in other Maltese works, like in the above mentioned Beheading of St John the Baptist, or in the St John the Baptist by Mattia Preti (Chiesa di San Domenico, Taverna).

October 4, 2017