Carlo Falciani introduces ‘Il Cinquecento a Firenze’

The Florentine independent scholar throws light on the ultimate exhibition he has co-curated with Antonio Natali at Palazzo Strozzi. Old masters have never looked so young before.

- Il Cinquecento a Firenze, Palazzo Strozzi, exhibition view. Ph Alessandro Moggi.

- Andrea del Sarto (Andrea d’Agnolo; Florence 1486‒1530), Lamentation over the Dead Christ (Luco Pietà); 1523‒4, oil on panel, 238.5 x 198.5 cm. Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Galleria Palatina, inv. 1912 no. 58.

- Michelangelo Buonarroti, (Caprese o Chiusi della Verna 1475 ‒Rome 1564), River God c. 1526‒7. Clay, earth, sand, plant and vegetable fibre, and casein model built around an iron wire core. Later interventions: plaster, iron mesh. 65 x 140 x 70 cm. Florence, Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (in deposito presso il Museo di Casa Buonarroti).

- Rosso Fiorentino (Giovan Battista di Jacopo; Florence 1494‒ Fontainebleau 1540), Deposition from the Cross 1521, oil on panel, 343 x 204 cm. Volterra, Pinacoteca e Museo Civico.

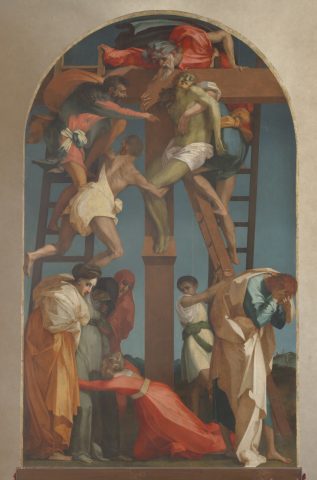

- Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo; Florence 1503‒72), Deposition of Christ c. 1543‒5, oil on panel, 268 x 173 cm. Besançon, Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, inv. D.799.

- Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci; Pontorme, Empoli 1494 ‒Florence 1557) Deposition 1525‒8, tempera on panel, 313 x 192 cm. Florence, Church of Santa Felicita.

- Francesco Salviati (Francesco de’ Rossi; Florence 1510‒ Rome 1563), Annunciation c. 1534, oil on panel, 237 x 171.5 cm. Rome, Church of San Francesco a Ripa.

- Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo 1511‒Florence 1574), Crucifixion 1560‒3, oil on panel, 450 x 248 cm . Florence, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine.

- Alessandro Allori (Florence 1535‒1607), Christ and the Adulteress 1577, oil on panel, 380 x 263.5 cm. Florence, Basilica of Santo Spirito.

- Maso da San Friano (Tommaso Manzuoli; Florence 1531‒71), Portrait of Sinibaldo Gaddi, after 1564, oil on panel, 116 x 92 cm. Private collection.

- Gregorio Pagani (Florence 1558‒1605), Madonna and Child Enthroned with Sts Michael Archangel and Benedict 1595, oil on panel, 233 x 156 cm. Terranuova Bracciolini, Church of San Michele Arcangelo.

- Alessandro Allori (Florence 1535‒1607), St Fiacre Healing the Sick (or Vision of St. Fiacre) c. 1596, oil on canvas, 404.5 x 293.5 cm Florence, Basilica of Santo Spirito, Sacristy.

- Cigoli (Lodovico Cardi; San Miniato 1559‒Rome 1613), Martyrdom of St James and Josiah 1605, oil on canvas, 305 x 215 cm. Pegognaga, Church of San Giacomo Maggiore.

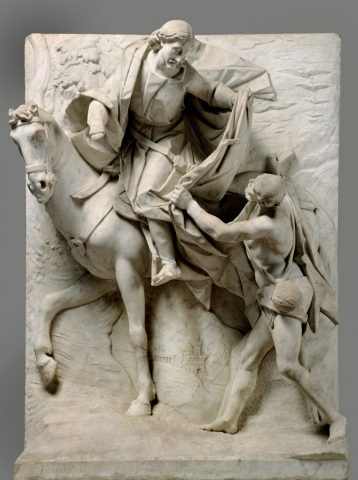

- Pietro Bernini (Sesto Fiorentino 1562‒Rome 1629), St Martin Sharing his Cloak with a Beggar c. 1598, marble, 140 x 100 x 48 cm o 139 x 101. Naples, Certosa e Museo di San Martino.

There is only a couple of people around that can put together an exhibition such as ‘Il Cinquecento a Firenze’. The show opened few weeks ago in the birthplace of the Renaissance. No other art historian or top museum director would have been able to obtain such a huge number of masterpieces. The general consensus is that it never happened before, and it will never happen again. At Palazzo Strozzi (info), where this dream show is hosted, the three main painted depositions of that golden age are sharing the same room. Suffice it to say that the one by Bronzino, a property of the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie in Besancon, returns to Italy for the first time after nearly 500 years. Until 22nd January 2018 it is on display side by side with the one painted by Rosso Fiorentino for Volterra and with that accomplished by Pontormo in 1528 for the Florentine Church of Santa Felicita. And this is only the exhibition’s second room…

Both pupils of art historian Carlo del Bravo – to whom the exhibition’s catalog is dedicated – the two art unicorns we are talking about are Antonio Natali, the former Director of the Uffizi gallery, and Carlo Falciani. This latter curated another apparently impossible exhibition that took place in Paris at the Musée Jacquemart André in 2015 – ‘Florence, Portrait at the Medicis Court‘. Mr. Falciani, an independent scholar and teacher of Modern and Contemporary art at Florence’ Accademia di Belle Arti, granted to CFA an exclusive introduction to the show. Here is what you may like to know before visiting it.

This exhibition is to be regarded as a polyphony of voices. It is an ensemble of 41 artists. Among them there are some aces – as Rosso, Pontormo and Bronzino – who are ‘playing’ together for the first time. Pierpaolo Pasolini already put the depositions by Rosso and Pontormo side by side in its short film titled “La Ricotta” (Curd Cheese, 1963); and images of the two outstanding altarpieces have been published on the same page in hundreds of art books. Yet they had never been placed so close to each other before. Bronzino is with them, five hundred years later he executed the deposition that Cosimo De Medici commissioned to him as a diplomatic gift to Nicolas Perrenot de Granvelle, Emperor Charles V’s mighty “Secretarius”.

When exhibitions involving so many fragile masterpieces take place one may wonder whether it really makes sense to move all these artworks from their original locations; or from the museums where they are preserved. I agree with the fact that many times it’s pointless. Still, this is not the case. Visitors rarely had the opportunity of seeing as up close as in this show most of the monumental paintings currently on display at Palazzo Strozzi, under ideal lighting. And, what counts more, the exhibition provided some of these artworks proper restoration. In fact, thanks to institutions such as the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi itself, or Friends of Florence, almost twenty pieces have been cleaned or restored for the occasion. As, for instance, the almost forgotten last painting by Bronzino, that is preserved at the Novoli market in Florence, in a plain church from the 1950s. It’s also the case of The River God by Michelangelo, that is on display in the first room. Darkened with age, the sculpture is now back to its original white.

The first room is representing the two main and long-lasting styles of the XVI century, those of Michelangelo and Andrea del Sarto. All the artists of that time had to settle accounts with the former, while Andrea del Sarto is still representing the most copied example of ideal perfection. The second room describes the variety of Florentine artistic languages, embodied by Rosso, Pontormo and Bronzino. Their styles are opposed to Vasari and Salviati’s ones, who are also presented in this room as followers of the “Romans” Michelangelo and Raffaello. And we could say that the Florentine way to naturalism, embodied by Pontormo and Bronzino, is the main discovery that Il Cinquecento a Firenze made possible.

The third room follows this long introduction and presents paintings executed after the Counter-Reformation of the Church. Allori, Stradano, Santi di Tito, and the recently restored crucifixion executed by Giambologna for the Florentine Basilica of Santissima Annunziata are representing the precepts on church furnishing adopted by the Council of Trent. The fourth room is about the variety of portraits painted during the second half of the XVI century; the fifth puts together the artists working for the so called “Studiolo”of Francesco I de Medici, a room in Palazzo Vecchio especially designed to house “rare and precious items” on the basis of a complex programme devised by Don Vincenzo Borghini. Room number six is about allegories and myths, while the two remaining ones enquire into the grey zone between the end of the XVI and the beginning of the XVII century with artists such as Santi Tito, Congoli, Giovan Battista Caccini, or Pietro Bernini, the father of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Antonio Natali and I have tried to avoid the idea of magnificence, which generally comes with the idea of decadence and characterized, for instance, the court of Francesco I. We were interested in other features of that golden age. That is why we decided not to include precious objects such as pieces of furniture or jewels. Instead we focused on the dialogue between painting and sculpture, and on their evergreen meanings. That is also why no drawings are on display. Understanding the importance that this medium had in Florence at that time requires indeed a dedicated exhibition. It would have made no sense to give only a few examples.

To conclude, we asked Mr. Falciani to suggest a playlist to listen to while visiting the exhibition.

I don’t think music from the XVI century would be appropriate. This show doesn’t aim at bringing the visitor back to the XVI century. On the contrary, it is intended to ‘sound’ with the ‘rhythm’ of a contemporary art exhibition; and that is why, for instance, all the big altar pieces are on display with no frame. If you need a soundtrack for your visit I would suggest something out of Brian Eno, or Die Antwoord, or a pop hit such as Revolution by Diplo. Many years have passed since that golden age, but human feelings are the same. If we want to save some ideas from the past we must be able to bring them back to the present. In this regard, have a look at the portrait by Mirabello Cavalori that is in the fourth room. It pictures a standing young man with his chest partially open to show his heart, which is bearing the words “PROCVL” and “PROPE”. It’s the allegory of the friendship, and probably also a tribute that the artist’s client paid to a lost friend. Isn’t it a timeless message?

November 7, 2017