Erwin Redl and the Bill Gates version of John Cage

Erwin Redl makes monumental art installations using light and computer technology, without any assistance from big galleries.

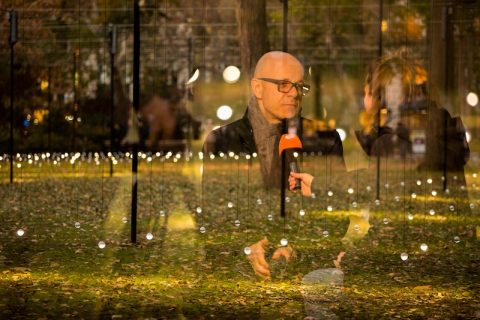

- Portrait of Erwin Redl with “Whitehot” at Madison Square Park, New York. Courtesy of Moorehart Photography.

- Installation view of “Whitehot” at Madison Square Park, New York. Courtesy of Moorehart Photography.

- Installation view of “Whitehot” at Madison Square Park, New York. Courtesy of Moorehart Photography.

- Installation view of “Whitehot” at Madison Square Park, New York. Courtesy of Moorehart Photography.

- Installation view of “Whitehot” at Madison Square Park, New York. Courtesy of Moorehart Photography.

- Installation view of “Whitehot” at Madison Square Park, New York. Courtesy of Moorehart Photography.

- Installation view of “Whitehot” at Madison Square Park, New York. Courtesy of Moorehart Photography.

An Austrian-born artist, who lives and works in the United States, Erwin Redl makes dynamic art installations using light and computer technology. Commissioned to create a public art project for Madison Square Park, without any assistance from big galleries, Redl has constructed a kinetic piece with 900 orbs of light that undulates in the wind and changes appearance according to the time of the day and season of the year. Conceptual Fine Arts recently met the artist in the park to discuss the making of his Whiteout project and to hear how it’s intended to impact our perception.

What’s your fascination with light?

I’m very interested in ephemeral media and underlying structures. I have a background in music but I also come from a family of furniture makers. Through studying electronic music I realized that I could combine my interests in technology and craft because the computer doesn’t care. I could use the same set of algorithms that are used to make music to make visual art. In this regard, John Cage’s openness to chance was very influential.

How did you come to work with it as an artistic medium?

I studied computer art at SVA and showed my work mostly in electronic arts festivals, but I was frustrated that it was centered on the machine. I was more interested in how the machine thinks. I saw it as a means to an end.

If you were to make a comparison to how you use light and the other forms of visual art what would it be?

It sounds funny, but it’s still drawing to me. It’s just a very precise delineation of space.

And if you were comparing your work to music what would it be?

I have a strong connection to minimal music, Steve Reich in that regard, and I have a strong relationship to the European avant-garde and contemporary music, Iannis Xenakis is one of my absolute favorites and he’s also a visual artist, and then Baroque music, obviously Bach. For me it’s this connection between abstraction and corporeality.

What kind of digital means do you use to make your work?

There are different steps in the process. It starts with a drawing but then moves into a 3D program like CAD, so that I can see angles and figure out the dimensions. Later on it’s spreadsheets, which I love because it allows me to organize my thoughts, which are very often expressed in numbers, in algorithms. I can actually design pieces on spreadsheets using elements of chance. It the Bill Gates version of John Cage!

Do you define yourself as a digital artist or light artist or something else?

Artist is good enough for me. I do a lot of kinetic work. The piece at Mad Square Park is kinetic, but it’s also interactive—interactive with the environment, not with the people. I also do unplugged works, such as sculptures and installations.

What kind of impact do you hope your Whiteout installation will have on the audience?

There are different levels. First, I want to stop people in their tracks and have them take in the environment. I hope that they will come back to experience it in different light, in different temperatures and in different weather conditions, such as rain, snow and fog and with the changing of the trees. It’s simply a matter of sharpening your perception.

What are the materials involved in its making?

The core material is light—bright, LED light, which is pretty much like what you have in a flashlight. It’s encased in a polyurethane ball. The bottom hemisphere is clear so that the light only shines down and the top half is opaque white, kind of like a lampshade. There’s a mixture of transparency and opaqueness. Then there’s the electronic structure with cable controls and power supplies. There’s also a steel structure that holds everything up—poles and cables. All of this magic disappears at night.

What’s the optimal time of day for viewing it?

It’s not a time rather it’s a time period. The best is just before sunset and just after it. It’s a period of time we call the magic hour. You have a lot of red light at sunset and it disappears it goes more into blue and the balls just appear to float.

And is there an optimal point of view for experiencing it?

No, it should be equally accessible from all points of view. That’s why I consider myself more of an installation artist than a sculptor.

Is it an immersive experience?

Yes, but it’s a different degree of immersion. The usual immersion would be that you could walk through the piece. We can’t do that because the lawn has to be replenished during the winter and there would be too much risk of damage to the piece. You can walk around it and perceive yourself through another you because you look through it and see another person on the other side, but since there’s a “ganzfeld effect” you think that person is walking in the installation. That’s why it’s titled Whiteout, which is a weather condition when snow alters visibility.

Does it move with the wind?

Yes, that’s one very important aspect of it. In science it’s called emergence, where the sum of the parts is bigger than the individual parts added together. Waves on the ocean are water molecules but as a unit together it creates a wave that’s more than the sum of its parts. It’s like seeing a pattern when viewing a flock of birds in the sky or a school of fish underwater. It’s the same with this piece, where 900 balls of light create undulating patterns caused by the wind. The two main parts of the perception of the piece are light and movement.

Is it also undulating through any electronic means?

Yes, I can control the brightness of the lights up to a certain degree because there’s a way that they are wired up and within those limits I can basically overlay electronic or virtual movement on that field. There are minimal wave patterns moving through the piece by electronic means as a counterpoint to the waves that are caused by the wind.

How will it evolve with seasonal changes?

The ground will change from green grass to a bed of brown leaves and then snow of winter and the fresh green grass of spring, with the birds and squirrels passing through. Metaphorically speaking, the canvas changes but my drawing stays the same.

Does it actually look as good as it does in the video animation that you created to preview it?

It looks different, and hopefully better. It will never have the same precision as a digital video. You lose the perfection but gain in the perception.

Is the ideal viewer someone who actually knows your work and comes to see it or the passerby who is stumbling upon it?

I’m always flattered when people know my work and can register the piece within a certain context of my work, but I’m happy that as many as 60,000 people a day have a chance to discover something new.

What’s the takeaway from this project for you?

I always learn from my projects. You climb a ladder to run cables and see so many things that could be done differently or may not have reached the full potential in relation to the context. You take those ideas out of the parameter and let them bloom elsewhere.

February 21, 2018