A family business: Querini Stampalia compares Mantegna and Bellini

Venice introduces the show about Mantegna and Bellini that the National Gallery is going to open next October by putting side by side their respective versions of the Presentation at the Temple.

- Bellini and Mantegna superimposed, elaboration by G Poldi

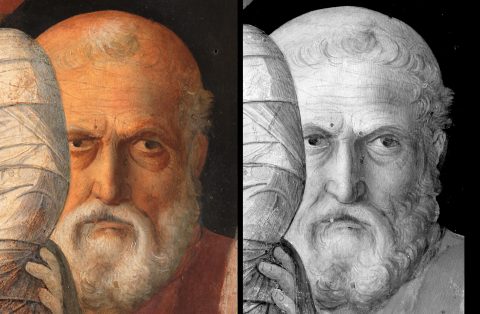

- Detail from Andrea Mantegna (on the left) and Giovanni Bellini ( mirror image, on the right), elaborated by G. Poldi

- Andrea Mantegna, detail of Joseph

- Giovanni Bellini, detail of Joseph in visible light and IR reflectography (G.C.F. Villa, elaborated by G. Poldi)

- Andrea Mantegna, detail

- Giovanni Bellini, detail in visible light and IR reflectography (G.C.F. Villa, elaborated by G. Poldi)

- Giovanni Bellini, detail of the priest in IR reflectography (G.C.F. Villa, elaborated by G. Poldi)

- Giovanni Bellini, detail of the priest in IR reflectography (G.C.F. Villa, elaborated by G. Poldi)

Mantegna and Bellini; what drove the young and already experienced painter Giovanni Bellini to copy the composition of his brother-in-law Andrea Mantegna years after this latter had painted it, maybe even two decades later? The matter at hand is a Presentation at the Temple in Jerusalemn, a topic approached by many artists at that time, and certainly treated in this case with the intention of creating a work for private worship. In the Mantegna’s version, housed at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin and currently on exhibition at the Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Venice (show design by Mario Botta), the work has been executed on a thin linen canvas nailed to the front of a wood panel. The painted part measures cm. 69×86. A young Madonna hands the Child wrapped in swaddling cloths to the Priest. From the background, the figure of Joseph stands out, thoughtful and old, while on the far sides of the painting Mantegna paints respectively a male and a female, younger than Joseph, who are possibly the self-portrait of Mantegna himself and the portrait of his wife Nicolosia, sister of Giovanni Bellini, and daughter of the great Venetian painter Jacopo Bellini, Giovanni’s father. Mantegna married her in 1454.

The copy by Giovanni Bellini, which belongs to the Fondazione Querini Stampalia, was painted on a wood panel and is slightly bigger (it measures around cm. 81×105). The larger surface allowed Bellini to insert two further figures at the opposite corners of the composition, a male and a female. To a painted fictive molding of ancient marble veining-white, pink and green, Bellini prefers a parapet of inlaid antique green gravel; the elegant dark brocade of Mantegna’s Virgin Mary is simplified and painted with pale light blue; other colours do change, opting for more delicate chromatic tones of white and red.

The iconographic variations are few, albeit significative. The ‘copier’ revises the taste; or, better, reinterprets the original work with his own idea of painting, which is also inspired by Humanism’s idea of the classical period. Yet it seems to be less interested in the architectural solidity and marmoreal rigour. Instead, Bellini pays more attention to capture the light and the atmosphere, thereby attenuating the sort of Donatellian rigidity of the faces and of the drapery of Mantegna’s, and reducing the sharp-cornered features. Bellini is also looking for a more intimate dialogue with the viewer, especially through the character he added on the right. Some scholars advanced that this latter figure is also a self-portrait, whose sharp face is akin to the one of the other character who is not looking towards the sacred scene, but in another direction, hence creating a feeling of disquietude.

Also the purpose of Bellini’s work may differ, albeit it is still unknown who commissioned it. We are only aware that the Cardinal and notorious scholar Pietro Bembo was one of the first owners of Mantegna’s version. It could be that Bellini’s painting hadn’t been commissioned but thought by the painter for himself or his own family, for instance as a wedding gift.

The execution techiques vary too. While Mantegna’s painting is a tempera on canvas, being it egg or glue tempera, as discussed in the catalogue, doesn’t really seem to matter, Bellini paints with oils, maybe oil and egg, on a poplar board. There is thus a mutation of the glossiness of the pictorial surface and of the relationship with light. This way Bellini distances from the ancient and elaborated taste that the Paduan painter loved to use, with his typical dense weave of thin brushstrokes on the canvas; the painting becomes more fluid.

Whereas the analysis previously carried out by Giovanni Villa and by Gianluca Poldi about these artworks and many others by Bellini and Mantegna showed that this latter had some afterthoughts, the panel painted by Bellini faithfully traces the central characters of the brother-in-law. Mantegna paints his artwork around 1455, and makes some important changes directly on the canvas, which have later been clarified by new and wider examinations performed in this instance at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. The changes particularly affect the Virgin Mary, who was originally located more on the left, farther from the Child. Mategna draws the two figures closer, possibly to emphasize the apprehension of a mother who is about to leave her fragile baby in the hands of another man; the Priest is reaching out to take him, still looking at the woman with a severe gaze, almost worried. Bellini decides to soften this gaze in his version. In the very first idea Mantegna didn’t seem to consider either the figures at sides or Joseph; he thought of a more essential dialogue between New and Old Testament.

Bellini doesn’t work on the brother-in-law’s cartoon, but on a copy of the final painting, which he traces over life-size, possibly through a semitransparent oil paper. Then he replicates the layout on the ‘gesso’ preparation of his own panel. He goes back to the drawing with brush, possibly with black ink, to then delete the remaining traces, which as a matter of fact don’t appear in the infrared analysis. The reflectography carried out in 2003 revealed the presence of a thick double-intensity contour mark which recalls with slight variations the drapery in Mantegna’s, as seen under Joseph’s face. The investigations also disclose a chiaroscuro line drawing, incredibly accurate and refined, executed to convey the volume and shadings of the figures, in order to emphasize the areas of light and shadow before turning to colour. For more than two decades this has been Bellini’s typical modus operandi, clearly reflected in this work situated between the end of the sixties and the first half of the seventies, that is between the Polyptych of St Vincent Ferrer and the Pesaro Alterpiece.

What has drawn Bellini to reprise, as he did with other works by Mantegna, the painting of his brother-in-law? We don’t know exactly, yet we could grasp it. He was probably looking for a long-distance confrontation, maybe moved by the necessity to asses his own artistic journey, which in his early years had indeed looked at the Paduan workshops. It represented a dig in his own root while stepping forward towards a more essential iconography, on black background, with a format which allows him to investigate the intensity of the faces, the dialogues of gazes and gestures, and will later become one of the Venetian’s favourite. It was a meditation.

This same essentiality leads us today to possibly love Bellini’s painting more than the original version. As Caroline Campbell points out in the Querini Stampalia exhibition’s catalogue: “nowadays that originality is the requisite that matters the most when judging the value of an artist, it is particularly hard to capture the intrisic link between imitation and innovation”. This topic of canon has characterised the art of icons, oriental art, and abstractism, minimalism, pop-art and jazz music in the Twentieth Century. This elegant exhibition at the Fondazione Querini Stampalia deserves a visit as it prompts the visitor to ponder over an important crux not as much of the history of art, as of making art.

November 25, 2020