Is Muntean/Rosenblum the Instagram’s forerunner?

A decade before the social networks were born Muntean/Rosenblum had questioned the Instagram format, and predicted its consequences.

![Muntean/Rosenblum, untitled [The sky’s a cloth…], 2018, oil / canvas, 85 × 126 cm, courtesy of Muntean/Rosenblum, Galerie Ron Mandos, Amsterdam.](https://www.conceptualfinearts.com/cfa/CFA-content/uploads/2019/02/05142018_jpg-Copia-640x439.jpg)

Muntean/Rosenblum, Untitled [The sky’s a cloth…], 2018, oil on canvas, 85 × 126 cm. Courtesy of Muntean/Rosenblum, Galerie Ron Mandos, Amsterdam.

Premise. Muntean/Rosenblum is a single artist. That is to say, as it often happens in these cases (look for instance at Guyton/Walker or Lutz/Guggisberg), the creative identity which bears the surnames of the two people making it counts more than their sum, and it has become something different from them. In a recent chat we had with Adi Rosenblum, she explained us that her relationship with Markus Muntean, who is also her life partner, has generated over the years something that goes beyond the couple itself. ‘We are together day and night. We share work and life. I think I could say by now that, at least on a professional level, but maybe on a personal one too, we have become one’.

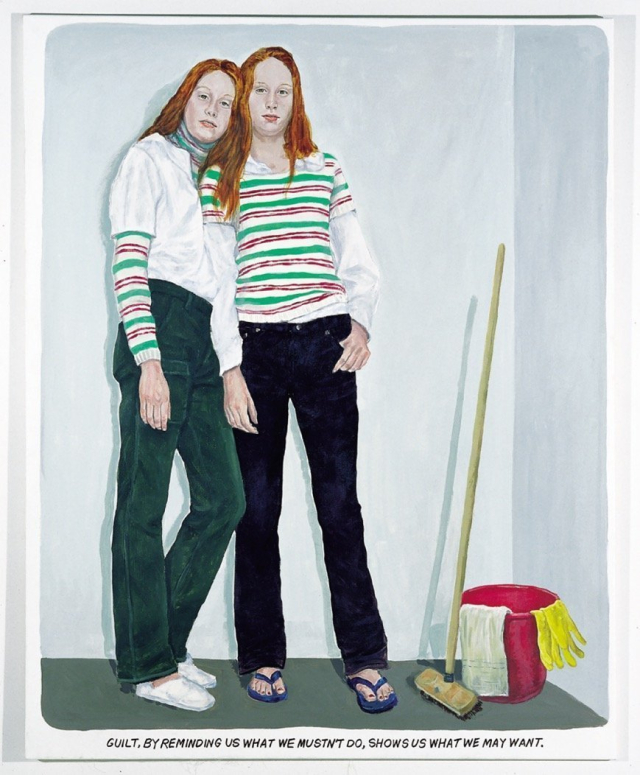

Muntean/Rosenblum, Untitled („Guilt, by reminding …“), 1999,

acrylic on canvas, 170 x 135 cm.

The recent solo-shows at MOCAK in Krakow and at MAC in A Coruña have certainly marked a turning point in Muntean/Rosenblum’s work. Now the performances that ‘happen’ with the paintings on the opening day keep on existing independently on Youtube. The cuts on the actors’ faces at MOCAK are still bleeding. ‘This is something we have been interested in for a very long time. There is a deep similarity between the artistic performances and the videos a lot of people spontaneously upload on Youtube. We believe that to a certain extent this platform can be compared to a museum‘. And because the public dimension of the artwork has been food for thought for Muntean/Rosenblum since their debut in the early 1990s, the choice of ‘existing’ on a platform like Youtube seems to come as the most natural consequence. ‘At this point – explains Rosenblum – it is not even necessary to say that we are dealing with art’. They’d rather be part of the flow instead of declaring a specific goal’.

Muntean/Rosenblum. The prophecy.

From Youtube to Instagram, it is but a short step. A more controversial and interesting issue seems to be coming up here. Indeed, whoever is familiar with the pictorial work of Muntean/Rosenblum as well as with the most popular social networking platform of today (at least for the art world) may have noticed a unique similarity. Two decades before Instagram summed up Facebook and Twitter thereby achieving the best combination of image and text, Muntean/Rosenblum had already started working on this very same relationship, with a format which was very similar to the one Instagram is known for. This similarity is even more thought-provoking if you think that, at least until a certain point, Instagram used only square photos.

Muntean/Rosenblum, Untitled („Before we know it…“), 2000,

acrylic on canvas, 200 x 250 cm.

In this respect Adi Rosenblum asserts ‘the market tends to provide a far too narrow interpretation of what painting actually is‘. Fair enough. Some social networks show once again how the image goes beyond the essence of the very same piece of art. The Mona Lisa ‘exists’ as an image in books, on the web, and million of people know it through channels and supports which are very different from the museum and the poplar wood panel it was painted on. The object is unique, while the image is endless. The same law generally distinguishes the object-work from its image, which is indeed protected by a bunch of negotiable rights. Social networks are thus a fundamental vehicle for the image before than for the painting, a vehicle ‘that we are interested in experimenting‘ explains Rosenblum. However social networks, particularly Instagram, are something that the painting of Muntean/Rosenblum has somehow been able to predict. The arts anticipate the effects: ‘In the past many people noticed how the characters of our paintings rarely communicate with each other, not even when they are grouped together. That same form of individualism we attempted to convey can be currently found in the billion of selfies that are posted everyday on the social media‘.

Moreover, Muntean/Rosenblum has always been working on the relationship between text and image too. It seems almost a prophecy. In her painting the word has always been assigned to another space, different from where the scene is happening, that looks like a sort of screen within the painting. Likewise, the social media are designed in a way that until recently you couldn’t add any text to the image. Muntean/Rosenblum was already on Instagram even before Instagram was born.

With regards to the written part in the paintings, Adi Rosenblum adds: ‘Text is for us what music is for a movie. It places the images within a certain atmosphere thus making them more expressive‘. In this instance we have the feeling that it is about the atmosphere of a reality represented as the reality would like to be, rather than how it actually is. There is a delicate sensuality in the characters who ‘are posing’ like the models of the collective imagination they are based on, that of advertising and fashion shoots. ‘Through the magic of painting we can create spaces which are exclusively pictorial, even when they look real‘ points out Rosenblum. Again, we could say the same about Instagram. Even though in this latter case it’s not sure we are dealing with ‘white’ magic, or ‘black’ magic.

Muntean/Rosenblum, Untitled (The Room was a Pool), 2005, oil on canvas, 220 × 260 cm. Courtesy of Collezione Giuseppe Iannaccone.

‘This aspect has often been misinterpreted. Many people argued that we intended to represent a certain generation, but it isn’t so. As a matter of fact, we started in the 1990s and we still paint the same themes. We have never really been interested in the generational debate. Media tend to get rid of what is old and, on the contrary, prefer to picture youth and its beauty. This is indeed what we have tried, and we do try, to portray. We are interested in the archetypes through which society represents itself, rather than in a single individual or social group‘.

Muntean/Rosenblum and their followers.

As the characters of Muntean/Rosenblum, also Anne Imhof’s ones have so far represented adolescents who are distant, unreacheable, fickle (perhaps), seductive (surely), sometimes weak, sometimes gifted with extraordinary skills, nevertheless always trapped in the image of them the media convey. But the premise they come from is different, that is a society which is nowadays at the mercy of those contemporary titans that in the 1990s were above all promises of a better future. We could add to this comparison the work of the early works of photographer Ryan McGinley, who also pictured the adolescence, attempting to capture, from within and with a hint of positive nativity, its extraordinary energy.

Anne Imhof, Angst II, 2016, performed at Hamburger Bahnof, Berlin. Ph. Stefano Pirovano.

Compared to McGinley or Imhof, however, Muntean/Rosenblum decides to adopt a traditionally artistic point of view, that of painting which, as such, cannot help but dealing with its own past. ‘There is something in painting that connects you directly to people’s heart, and this is what still fascinates us‘ says Rosenblum. Their figurative choice leads to emotions before than to the intellect. The source is often photography. Up to a certain point Muntean and Rosenblum turned to fashion magazines, then they searched the web, using especially Flickr and getting inspired by private archives. Every now and then they also work with models, selected through casting and agencies. Once the characters and background are chosen, Muntean/Rosenblum draws a sketch on Photoshop, then moves to painting, which at the moment is focused on shades and artificial light. While painting, Muntean/Rosenblum listens to audio-books, from where the titles of the artworks are actually taken.

Muntean/Rosenblum’s studio in Wien, 2019.

November 25, 2020