Emerging artists to watch: Srijon Chowdhury and his dark positivity

For Srijon Chowdhury painting is a site of consciousness, where light always wins over darkness and symbols are messengers announcing the future.

We saw paintings by Srijon Chowdhury for the first time in person a couple of weeks ago, at Antoine Levi in Paris. This has reinforced our idea that computer or smartphone screens aren’t reliable sources, and cannot replace direct experience. The painting coat covering Srijon Chowdhury’s pieces is neither compact nor shiny. Quite the opposite, you have the feeling the coat is thinning out, thereby creating thousands of wrinkles which give the surface glares that are similar to the ones typical of silk; at times the light seems instead to be trapped thus making the chromatic impasto extremely dark. His colours tend to be more silky rather than saturated. When you are in front of these pieces, you immediately realise that Chowdhury is as technically refined as he is in the subject-creation, albeit in a very different way from what the pixels would imply.

Srijon Chowdhury, White Roses, 2018; oil on linen, cm. 30,5 x 40,6 Courtesy the Artist and Antoine Levi, Paris.

Indirect autobiographical elements.

Let’s take a step back. Srijon Chowdhury has been in contact with art since he was a child, in Dahka, where he lived until he was 11 years old – then he moved to Minnesota, his mother’s birthplace. His father, who was born in Bangladesh, owned a contemporary art gallery in Dhaka for a few years. Named La Gallerie, the gallery mainly dealt with local artists. Akku Chowdhury was also a collector of architectural artefacts and traditional sculptures from his country. But, most importantly, he was one of the founders of the Liberation War Museum in Dhaka, which opened in 1996 in order to commemorate the War that led to the independence of Bangladesh in 1971. Mr. Chowdhury directed the museum from 1996 to 2002 basing its activity on first principles such as freedom and condemnation of any crime committed in the name of religion, ethnicity, or sovereignty. Before his child was born, Akku Chowdhury fought in that war, won by the Bangladesh forces thanks to the intervention of the Indian army. This is where the darkness that at times appears in Srijon Chowdhury’s paintings probably come from. And this is also where his love for life is rooted: “it is amazing to be alive”– mentions Chowdhury at some point of our meeting.

Srijon Chowdhury’s

Chicken Coop Contemporary, Portland.

From Bangladesh to the States.

The artist, who is 32 years old and lives in Portland (Oregon) didn’t take painting seriously at least until he went to college, in the United States. “In College I started to care more about art and painting ended up becoming the medium I focused on. I believe it is more direct than sculpture or print making, that is what I was initially interested in” he says.

There is an old chicken coop in the garden of the house where Chowdhury today lives with his family (his partner and three children). In the chicken coop he organises art shows “Opening this gallery was a way for me to keep connected with artists outside of Portland, as the art scene here isn’t that big. The gallery is about maintaining connections and bringing to Portland art that I want to see and engage with”. The artist describes Portland as a beautiful, green place. “For the last two years I’ve been working part-time in a botanical garden which is a five-minute walk from my house. There is an abundance of natural beauty here, and a peaceful slowness as well. Everything is close-by. It’s a kind of insular world”.

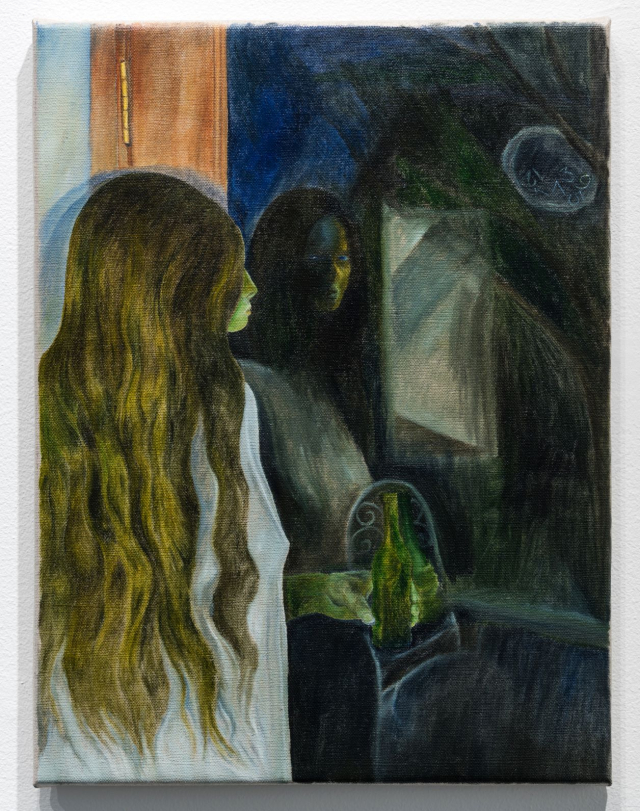

Srijon Chowdhury, Mirror, 2018; oil on linen, cm. 40,6 x 30,5 Courtesy the Artist and Antoine Levi, Paris.

Srijon Chowdhury, Reflection, 2017; oil on linen, cm. 61 x 51 Courtesy the Artist and Antoine Levi, Paris.

This sort of ‘insularity’, as Chowdhury calls it, engenders scenes that are instinctively banal, populated with simple objects, where not much is happening. “It’s Portland that gives me this kind of thinking space that is echoed in the painting”. The environment, then, is reflected in the pictorial language, thus overcoming social, geographical and temporal boundaries. Working within a tradition – painting in this case – could also mean not being afraid of being understood. “The act of looking is simple, and I do look around. Lately, for instance, I’m interested in the Italian mannerist painting, but also in the French symbolism of Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau. I am looking at Grant Wood and American painting from the thirties and at Otto Dix, who is also a painter from that time and works in a very similar manner to Grant Wood”.

Srijon Chowdhury’s solo exhibition at Antoine Levi, Paris. Courtesy the Artist and Antoine Levi, Paris.

Photograph: Aurélien Mole.

Srijon Chowdhury’s tecnique.

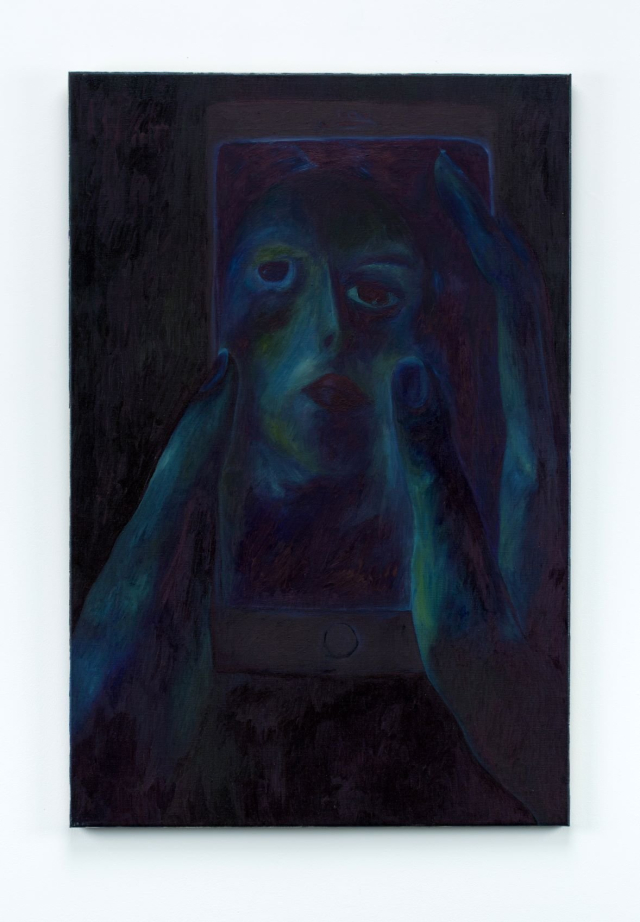

Despite how sophisticated the result appears to be, the pictorial process through which Chowdhury creates the image is rather essential. The artist doesn’t do any preparatory drawing on the canvas, where he prefers to apply the colour directly – here is the immediacy we were talking about at the beginning. Instead, before he starts painting, Chowdhury makes some sketches, which juxtapose with pictures he takes himself, books, his own computer or smartphone. Everything stands by the easel, while the painting takes shape. Sometimes this happens in just one sitting. However, especially since last year, Chowdhury has been trying to work on more layers, hence the composition takes a bit longer, generally a couple of weeks. Contrary to what one may think, the artist says it was only recently that he began to feel more comfortable with small formats (while for a longer period he preferred to work with larger formats).

Srijon Chowdhury, Glowing glory, 2018; oil on linen, 16×12 inches. Private collection, New York.

Symbols announcing the future.

Certain painting is made to represent ideas, facts or people who already exists. It is a different matter if you want painting to be a starting point for new narratives. Symbols, in this respect, could be very effective tools, not to illustrate subject matters, but to think about the future. “Lately I’ve been interested in symbolism and tried to think my painting in this term, with regards to climate change, for example, or to the calamities that can follow. I am painting this sense of dread and anxiety that these thoughts bring about.” What is the future going to be like? The answer, according to Chowdhury, has to be looked within everyday scenes, or in his ‘The world on fire’ paintings (see the picture below). The future lives in the ordinary “but it seems that the window of hope gets smaller and smaller everyday that goes by”. In Chowdhury’s artworks this hope is often entrusted to light that emerges from darkness, thus defining the surfaces, disclosing the shapes, caressing the characters. Light is, for the artist, also beauty that, he tells us, he tries to put in every painting. “It’s important to me that the paintings are objectively beautiful. Even in the darkness, or in the fear, there still could be beauty, and the hope that comes from it. There is a lot of beauty to be seen, at least here in Portland, and every second I try to take everything in, and remind myself how amazing it is to be alive.” Chowdhury’s images are thus thought to seduce and hypnotise us (think of the burnt out candles) with compositions and, above all, colours. At this point we should point out that there are no specific autobiographic reasons behind the darkness, besides those ‘indirect’ ones we mentioned previously. “I have a pretty good life” admits the artist. And certainly he is talking about that sort of happiness that only intellect is able to produce.

Srijon Chowdhury, Candle, 2018; oil on linen, 16×12 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Srijon Chowdhury, Airplane, 2018, from ‘The world on fire’ series; oil on linen, cm. 40,6 x 30,5 Collection Nerina Ciaccia & Antoine Levi, Paris.

Srijon Chowdhury, Alizarin shirt, 2019; oil on linen, cm. 76,2 x 61 Courtesy the Artist and Antoine Levi, Paris.

September 25, 2019