Margherita Moscardini reveals where sustainable art can be found

Margherita Moscardini, the Municipality of Reggio Emilia and Collezione Maramotti give birth to the first European extra-territorial fountain and reopen debate on public art.

Margherita Moscardini, Inventory. The Fountains of Za’atari, 2018, still da video, formato 4k, 31 min. / video still, 4k format, 31 min.Il video-documento è stato girato in Giordania tra il settembre 2017 e il marzo 2018 / The video-documentary was filmed in Jordan between September 2017 and March 2018. Winner Italian Council 2017 MiBAC- DGAAP. Courtesy Fondazione Pastificio Cerere, Roma © the artist.

—

“The work [that is the work of art] is elsewhere” answers Margherita Moscardini when, while visiting her current show at Collezione Maramotti, we question the artist about the visual side of her ‘work’ on Za’atari refugee camp. Here, in the Collection’s Pattern Room, in conjunction with the opening of the Fotografia Europea festival in Reggio Emilia, Moscardini presents the first complete version of her artistic ‘device’, how she calls it. The first fountain is to be found in Parco Alcide Cervi in Reggio Emilia. Soon this will become a ‘hole’ of extraterritoriality on the city’ soil; the Municipality of Reggio Emilia has indeed been the first one to buy the sculpture by the artist modelled on one of the courtyards with fountains of Za’atari camp, thanks to the support of Collezione Maramotti. The legal process to recognise the status of this small piece of land where local laws are suspended will soon be completed. According to the map of Za’atari drawn by Moscardini this is fountain number 32. The Royalties on the Emilian copy will remunerate its designer, Fida’ Khalid Qazaq, who currently lives in Za’atary district number 4 with his family and designed that fountain out of necessity – water is a main problem at the camp.

Margherita Moscardini, Mahallat el-Ghouta 94, Block 8, District 4, 2019, marmo / marble, 55 x 647 x 420 cm. Parco Alcide Cervi, Reggio Emilia. Progetto The Fountains of Za’atari, Collezione Maramotti. Ph. Andrea Rossetti.

Margherita Moscardini, elsewhere.

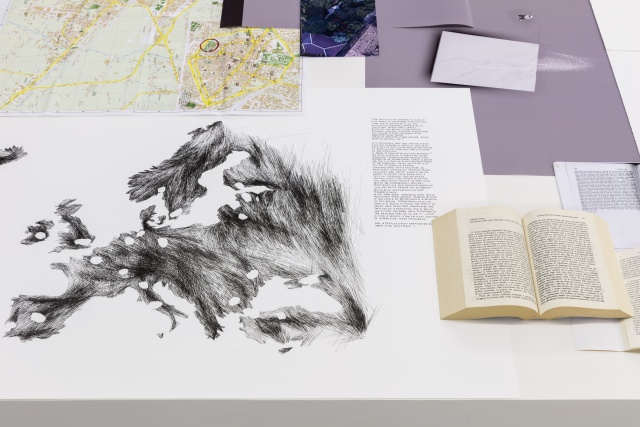

For Moscardini “Elsewhere” means beyond the form, and this is despite turning the Reggio’s fountain literally upside down as compared to the original one– now the piece of stone reproducing the courtyard lays over the fountain vessel. “Form matters a lot to me- points out the artist. But I think that the core of this project, besides its forms, lies specifically in it being a device, and acting in the present time, thus creating a place which is not subject to the sovereignty of any state”. Here the elsewhere we are talking about. On the left wall of the Pattern Room there is a big map of Za’atari and its fountains. The camp at the moment hosts around 80.000 people, in a place non-place whose border is marked by barb wire and tanks. To transfer the drawing onto the wall the artist used the spolvero technique, employing as pigment soil from over there. When looking at the map, if you happened to have read My name is Red by Orhan Pamuk you can’t help thinking about the fountains of Istanbul, and from there jumping to those of the Venetian campi, true architectural fossils which have escaped the concrete jungle. On the long wall, parallel to the windows, there is a handcrafted metal rack where the drawings of all the Fountains of Za’atari are lining up. On the wall parallel to the map there is a video that shows the various passages of the project thus giving a visual dimension to what we are talking about. Just opposite there is such a big pedestal, as tall as a child, that could actually holds up a monument, but that in this instance serves as a support for writings and documents that describe the work of art, its mental structure, its cultural references (Hannah Arendt and Giorgio Agamben above all), and how it works.

The Fountains of Za’atari is a device: 61 models of courtyards with fountains to sell to European cities and civic institutions so that they could be reproduced as public spaces. The ‘royalties’ will be paid to the designers of the fountains, and the sculptures on European soil will be bestowed extraterritoriality.

Immunity spaces, black holes and power vacuums upon national soil?

(ink writing on the above mentioned pedestal).

Margherita Moscardini, The Fountains of Za’atari, Veduta di mostra / Exhibition view, Collezione Maramotti, 2019.

Margherita Moscardini, The Fountains of Za’atari, Veduta di mostra / Exhibition view, Collezione Maramotti, 2019. Ph. Andrea Rossetti.

Public and private.

“I started to work on Za’atari because I felt the need to reflect on this place. I’ve identified the courtyards with fountains as sculptures. Of course, not all the 80,000 residents of Za’atari are artists, but some of those who built their own courtyard with fountains inside their homes could actually be seen as such. I restrict myself to only selling legal black holes on the national soil, thus trying to foster the camp’s economy. I’m also promoting the idea that the refugee camp should be thought as a real town that is destined to last. If conceived otherwise, the camp (not necessarily Za’atari’s one), could become a virtuous example for our future cities, possibly to export. Each epoch has generated its own urban models by interpreting the needs of its own time. The future of our civilisation is mass human migration. If camps were to be rethought as virtuous models of urban development, then they could actually become a new political structure which goes beyond the notion of ‘nation-states’. Therefore my work is a device. There was the possibility to meet a need and I have simply tried to seize it. As author, as artist, serving not only the arts but a urgency of this time doesn’t mean being less of an artist: it means believing that art is still a huge project, which only by taking into account and acting within these needs could free itself from its being self-referential and from its own poor patterns. Only then, it could actually go back to being that extraordinary project which is able to move mountains.”

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) refugee camps remain in use for 17 years on average. The Za’atari refugee camp was founded in 2012, on a semi-desert area of northern Jordan. It housed a part of the 6 million Syrians who, because of a civil war still ongoing in their own country, had to leave everything behind and escape abroad. In 2014 the camp’s population reached 150,000 people, making it the second largest refugee camp in the world. At that time the biggest one was Dadaab camp in Kenya, home to 350,000 people. Today it’s Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh which hosts more than 900,000 refugees fleeing from Myanmar, the majority belonging to a Muslim minority group.

The possibility Moscardini talks about is the Italian Council 2017, that is a competition launched by DGAAP – Directorate-General for Contemporary Art and Architecture and Urban Peripheries of the the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities (MiBACT) – in 2017 for ‘the valorisation of Italian contemporary artistic creativity abroad through the production of works of art, residency programmes and support for Italian artists participating in international contemporary art events (such as Documenta, Manifesta, etc.)’ – as stated on the Ministry’s website. The Fondazione Pastificio Cerere in Rome invited the artist to take part to it. Moscardini’s work on Za’atari is thus the result of public funding, and the freedom you perceive in her approach is thus the expression of a democratic institution, which the contribution of a private collector (in this case Collezione Maramotti) helped to echo by responding to a request, that is undoubtedly ethical before than being an artistic one. Indeed, it is within this dimension that art could actually find herself again and its fundamental ‘commitment to act, being aware of its own time’ (Moscardini). Not because market is an enemy, or rather because art can’t actually be a profession. But because art is a social resource too, (as we stressed in our writings dedicated to Berenice Olmedo and the art center funded by Ibrahim Mahama‘s in Tamale) and like every resource also art has to be respected, not exploited. Else, also the market could cease to exist at some point. Works of art, as opposed to shares, are emotional goods, just like the people who create them (P. Klossowsky, Living currency, 1970).

Margherita Moscardini, Inventory. The Fountains of Za’atari, Margherita Moscardini, Installation View at Fondazione Pastificio Cerere, photo by Andrea Veneri, Courtesy Fondazione Pastificio Cerere and the artist.

A promise for the future.

From Moscardini we learn that there are schools, mosques, sports facilities, ATMs, shops (more than 3000) in Za’atari; there is also a street ironically named Sham-Elysèes (Sham is the ancient name for Damascus). She has visited the camp many times between 2017 and 2018, thanks to the support of the Italian Embassy in Amman, Jordan. The economic system is based on E-vouchers, connected to a bank account, from where the person can withdraw cash allowance. At the camp’s supermarkets you pay through the iris scan system. Electric energy comes from a huge solar power system. “These cities can actually become virtuous models of innovation, also from a technological point of view. In a matter of few years, the tents have been replaced by containers, then to an agglomeration of containers placed around a courtyard, typical of the Arabic architecture.”

Together with Moscardini in Reggio Emilia we have been lucky enough to meet also Kilian Kleinschmidt, former UNHCR official and field coordinator of Za’atari camp between 2013 and 2014. Today Kleinschmidt is the Chairman, also founder, of the platform Swtixboard which aims at ‘connecting the world’s best capacities with the needs of disadvantaged people’. This project’ slogan couldn’t be any clearer. He thinks of Za’atari as a place where extraordinary human resources are ready to express themselves if given the most suitable conditions for this to happen. Moscardini managed to develop the idea of the fountains also thanks to his support. With Kleinschmid we touched upon many topics, but above all we considered how it would be possible for those cultural functions that characterise ‘normal’ cities to happen also in critical situations like the ones in refugee camps. Indeed, as Kleinschmidt points out, one of the real issues in the refugee camps around the world is that at some point ensuring essential resources like running water, food and electricity may no longer be enough for the life to really flow. Advanced forms of social interaction, like trade, religion, sport or culture are needed. There is a concept that comes up regarding the idea of home, that is also the deepest meaning of the Fountains of Za’atari (and Reggio). What happens to this idea when people are deprived of the possibility to go back to the place they belong to? Home is indeed within ourselves, and the objects we surround ourselves with (works of art included) are nothing more than a projection of this idea. The house is thus the identity we recognise ourselves within, although stateless.

November 25, 2020