Verrocchio and his workshop: a lesson for the future of the arts

‘Verrocchio master of Leonardo’, the first show dedicated to Da Vinci’s mentor, asks a crucial question: is art to be studied or learned by practice?

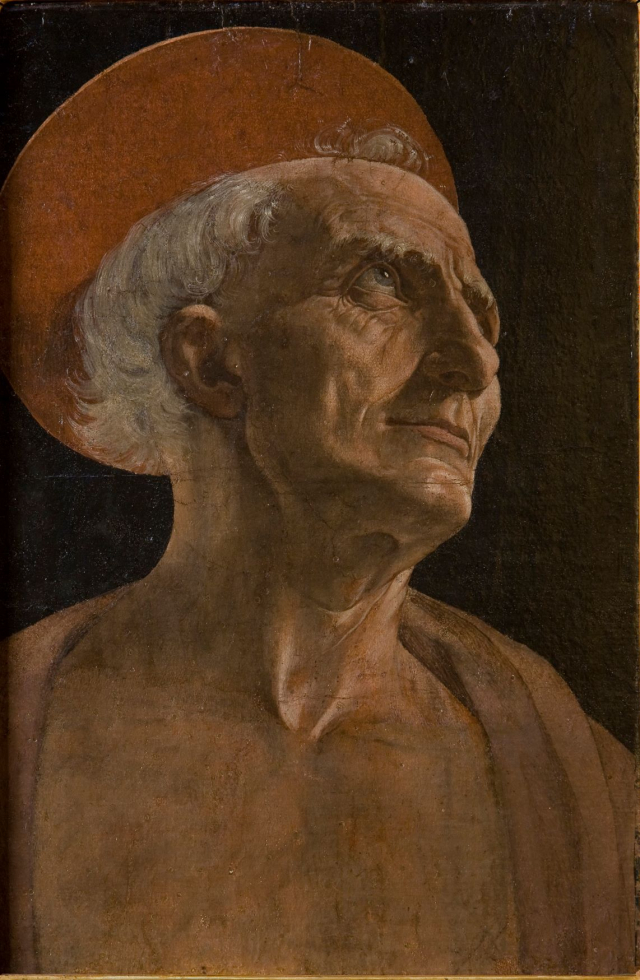

Andrea del Verrocchio, Saint Jeromec. 1465–70, tempera on paper applied to panel, 40 x 26 cm. Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi.

It’s hard, after visiting the first mono-graphic exhibition ever dedicated to Andrea del Verrocchio, to resist the temptation to project the Renaissance artist into our present time. Pursuant to the famous saying by Oscar Wilde we thus shall yield to it. We also shall try to assess whether Andrea del Verrocchio, that is Andrea di Michele di Francesco di Cioni, could actually embody a role model to look up to. Perhaps the answer we are all looking for lies in his technique and in his workshop’s microcosm.

Verrocchio is born in Florence in 1435. Lorenzo de’ Medici comes to power in 1469 when he is only 20 years old. He will pass away in 1492, three years after Verrocchio’s death. However, while The Magnificent dies at his villa in Careggi surrounded by the people he loves the most, amongst which Pico della Mirandola and Poliziano, Verrocchio passes away in Venice, where he was working on the equestrian statue dedicated to another fundamental character of his time, the condottiero Bartolomeo Colleoni, Captain General of the Republic of Venice from 1455 to 1475. Many art historians, starting from Federico Zeri, have pointed out how Lorenzo il Magnifico purposely intended to avail himself of the artists grown under his philanthropic wing as tools to culturally penetrate foreign powers – a bit like Hollywood in the American Century, or Google nowadays. This is also why Verrocchio is in Venice, Pollaiolo in Rome, Leonardo da Vinci leaves for Milan to work for another condottiero, Francesco Sforza. Lorenzo’s aim was to create an image of Florence, just like luxury industries tend to do today, which not by chance are undoubtedly the most active players in the art-world – while other collectors, equally wealthy and often owners of big companies, prefer to maintain their passion within their private sphere – such as Michael Hilti for example (link to our interview with Michael Hilti).

Andrea del Verrocchio, Bartolomeo Colleoni, 1480-1488, bronze, Campo San Zanipolo, Venice.

A cultural penetration.

According to ‘Cronica’ developed by Benedetto Dei in 1473 at that moment in time there are in Florence 40 art workshops, 44 goldsmiths, over fifty carvers, 80 woodcutters. The Magnificent’s policy directly affects the real economy, and if on the one hand you can actually recognise the plan we were mentioning earlier, on the other, it is reasonable to think that the demand for Florentine products is just the natural consequence of their high quality. Artists from Florence go abroad simple because they are the best around. In this regard the monument dedicated to Colleoni is rather a case in point; it isn’t cast by Verrocchio – who sadly passes away when the work is still a wax model, – but by the Venetian Alessandro Leopardi, who is commissioned by the Serenissima to cast the sculpture in bronze, despite Verrocchio specified that the work should have been finished by one of his best pupils, Lorenzo Credi. Historiography agrees that as far as attention to detail is concerned, the results don’t live up to Verrocchio’s best bronzes (Christ and St. Thomas, David, Putto with Dolphin), and this regardless of the fact that Venice actually wanted to scale down Colleoni’s post mortem ambitions – the monument, erected at his own expenses, was in fact installed in Campo SS Giovanni and Paolo instead of Piazza San Marco, as stated by the condottiero in his will.

Andrea del Verrocchio, Winged Boy with Dolphin, c. 1470–5, bronze, 70.3 x 50.5 x 35 cm. Florence, Musei Civici Fiorentini – Museo di Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. Ph. CFA.

Andrea del Verrocchio, David Victorious, 1468-1470, detail, bronze with traces of gilding, 122 x 60 x 58 cm (maximum depth). Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. Ph. CFA.

The multi medial workshop of Verrocchio.

Moreover, Lorenzo Credi was renowned for being a painter rather than a sculptor, and this is an important element to understand the role of the artists and how the workshop operates – Verrocchio commissions Credi an important work like The Madonna di Piazza, for the Pistoia cathedral. From this perspective Verrocchio is much more similar to Olafur Eliasson (link to our interview with Eliasson) than one would think, and in this instance Lorenzo Credi could be starred by Tomas Saraceno, that is an excellent student who is asked by his master to interpret his own ‘artistic’ attitude. In Verrocchio’s workshop, everyone does everything, according to their own talent, and the disciples of the master ‘were not few’ as Vasari reminds us. This is where Leonardo Da Vinci learns to draw, model clay, paint and possibly to cast in bronze too. The same Leonardo, then quite young, assists Verrocchio in the painting of the Baptism of Christ for the the Monks of Vallombrosa (he paints the angel holding the clothes and probably part of the background). The famous Putto with dolphin, element of a fountain located in the Medici villa of Careggi, has been attributed for many years to Leonardo. The marble bust of a Lady with Flowers by Verrocchio (now on show at Palazzo Strozzi) and the portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci by Leonardo (acquired by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C for $7.5milion from the Princely House of Liechtenstein! Link to our interview with Prince Hans-Adam II) have several contact points, especially if you take into account the study of hands that many scholars, amongst which Pietro Marani, believed that Leonardo carried out in preparation for the portrait of the Florentine noblewoman but that Francesco Caglioti, author of the sheet in the catalogue, considers instead to have been drawn for the portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, the famous Lady with an Ermine. The drawing, coming from the British Royal Collection, is now exhibited at Palazzo Strozzi close to the Lady with Flowers. The Ginevra de’ Benci did have hands, but then the canvas’ bottom part was cut. The same Verrocchio, certainly more experienced in sculpture, at some point decides to focus on painting. And what he looks for in the image, that is the attitude underlying its formulation represents the starting point for Leonardo, above all, but also for Perugino, Bartolomeo della Gatta, Lorenzo di Credi, o Domenico Ghirlandaio, all active in Verrocchio’s workshop. That is to say: study of the reality and attention to details, ornamental richness, and that clearness that Leonardo will then give up in favour of a softer painting and a certain level of continuity amongst the various elements – given that, we can be even surer nowadays, we are all part of the same cosmic pattern. The David cast in bronze by Verrocchio between 1468 and 1470 includes all these elements, together with a formal delicacy which is extraordinary effective from a psychological point of view. The same applies to his masterpiece, the group representing Saint Thomas doubting, executed between 1467 and 1483 for the most important external niche in the Church of Osanmichele, in Florence where the Florentine art guilds paid homage to their patron saints and where Verrocchio worked with his master Donatello, who made for two statues, Saints George and Mark.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452–Amboise, 1519) Woman’s Arms and Hands; a Small Man’s Head in Profile c. 1474–86, silverpoint and metalpoint, highlighted with brush and white gouache, with later overdrawing of outlines in soft, grayish black chalk, on pinkish-buff prepared paper, 215 x 150 mm. Windsor Castle, Royal Library, The Royal Collection Trust, inv. RCIN 912558 (lent by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II). Royal Collection Trust.

Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Ginerva de’ Benci. 1474-1478, oil on board, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Student or apprentice?

The historic leap is daring, yet promising. If it could not be that difficult to compare the cultural plan of Lorenzo de’ Medici with the strategies of luxury companies, which seem to be seizing, in our society of social inequalities – especially in Europe – spaces which democratic institutions have guiltily lost control of, it would be not that easy to find in the present time models which can be compared to Verrocchio and his workshop. Rarely masters of our time grow pupils. There are no schools. There is no ‘manner’- as it happens at some point, after Verrocchio, with the ‘modern manner’ (thoroughly described by another extraordinary exhibition held at Palazzo Strozzi, The Cinquecento in Florence – link to our review). Contemporary art seem to be living in an eternal expectation of what might happen tomorrow which implies that none really ever lives in the present moment (here how in 1996 Lucien Bilinelli spotted this problem). Nowadays artists’ education is entrusted to academies and universities, which if on the one hand do share with renaissance workshops their being cross-disciplinary, on the other they don’t seem to be able to offer that ‘level’ of confidence that only direct work experience can grant. Thus, we end up having thousands of more or less educated students, but no real apprentices that at some point could hope, with their talent, to overcome their masters. Or at least, to go beyond them.

Andrea del Verrocchio, Sleeping youth, 1465-1475, terracotta with traces of polychromy, Berlin Staatliche Museen.

November 25, 2020