Sophie Varin reads Thomas Pynchon

For this At The Show With The Artist, Sophie Varin discusses Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 in relation to her own contemporary miniatures.

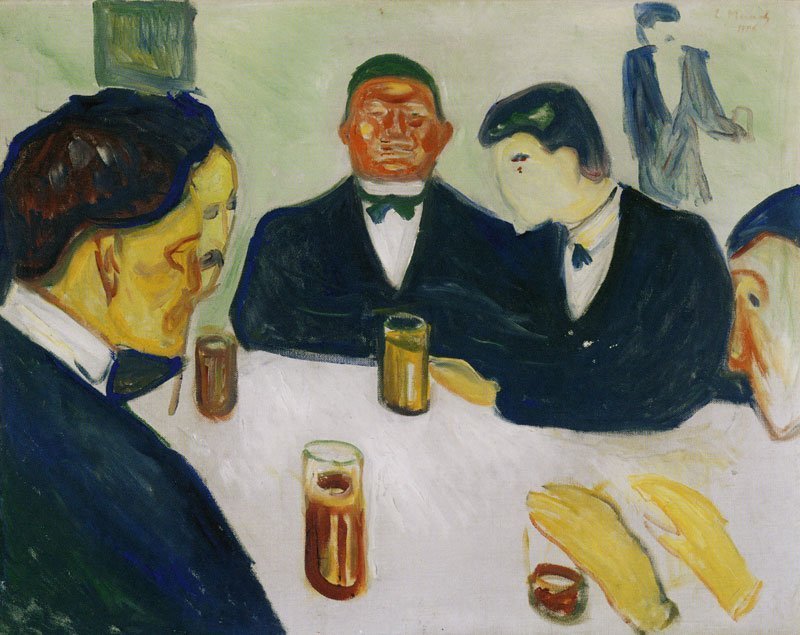

In medieval Europe, miniatures were small illustrations decorating books and codices of religious nature, sometimes depicting the everyday life of common people. These marginal, painted little spaces can now be seen as a glimpse of the scribe’s attitudes, hints of what they would think in their business of copying the canonical scriptures. If there was any individual perspective in the scribe’s head, a contemporary artistic interpretation, miniatures would illuminate it like an open window does a darkroom. Sophie Varin’s small scale paintings—her miniatures—are similar glimpses, also illuminating something that should not necessarily be illuminated.

Hailing from Paris and trained in Rotterdam, the young artist and writer investigates human themes with striking insight, subtly exposing aspects of them that would otherwise be left unspoken; let’s call it a matter of politely distressing the surface politeness. In her words, her artistic pursuit is one of a formal expression of human adaptability—or lack of it—to social contexts. It is with these tropes in mind that we spoke with Sophie Varin about a novel, one full of metaphorical miniatures. (check our lists of novels dealing with visual art here and here)

The Crying of Lot 49

In Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, human adaptability—or lack of it—is narrated through a grippy tale of detectives, conspiracies, and what the writer calls “gemlike clues.” These are short but effective glimpses into different realities, which nonetheless are never completely exposed. The novel eventually leaves us but with a sense of this pattern, the feeling that there might be something we should know about things, that the reality outside of us is more than we think. Likewise, Sophie Varin’s artworks, along with her own detective novel that was shortlisted for a literature prize, have prompted similar emotions in us.

After suggesting to work on The Crying of Lot 49, Varin begun by bouncing back this dense passage from it:

[The protagonist Oedipa] could, at this stage of things, recognize signals like that, as the epileptic is said to—an odor, color, pure piercing grace note announcing his seizure. Afterward it is only this signal, really dross, this secular announcement, and never what is revealed during the attack, that he remembers. Oedipa wondered whether, at the end of this (if it were supposed to end), she too might not be left with only compiled memories of clues, announcements, intimations, but never the central truth itself, which must somehow each time be too bright for her memory to hold; which must always blaze out, destroying its own message irreversibly, leaving an overexposed blank when the ordinary world came back. In the space of a sip of dandelion wine it came to her that she would never know how many times such a seizure may already have visited, or how to grasp it should it visit again.

She mentioned that she found this quote interesting in terms of the manipulation of focus, the drift of perception present in the novel. In a way, the gemlike clues would fork the main tale into many others, and for Varin, this is an “idea of a failing epiphany, of not being exactly on point, or on time.” She continued that for her “there might be something about trying to sneak peek from the corner of your eye and not being completely able to grasp entirely. Maybe there is some frustration in reachability and accessibility.”

A Moment of Frustration

The protagonist of the novel never claims she fully understands what is happening around her. She is not deeply affected by hindsight bias, that is this tendency for people to perceive events that have already occurred as having been easier to understand than they actually were. For Varin, “what comes after this moment of frustration is the mental reconstruction, which often implies a fantasized deviation, and maybe that’s the most interesting moment. Because that’s where the narration becomes collaborative somehow. A collaboration between what happened (if it even exists on its own?), who’s remembering it and why, and how, and who’s retelling it and how. And then of course even the ‘truth’ of what happened becomes completely circumstantial. Everything is true, but some parts just benefit from more attention than others. Like you don’t see something that is here until you are made aware of it.”

This collaboration between events and the protagonist is for us mirroring the collaboration between the scenes in Varin’s pictures and the gaze of those looking at them. As Varin says, this is “a sense of mutual bust of both the viewer and the characters of the painting;” let’s call it the politely distressed politeness of slowly opening a door and be half surprised/half embarrassed in finding out what is behind—what are those characters really doing? Likewise, they themselves would stare back at you as an intruder, their faces showing uneasiness if not slight anger.

Ambiguities

There is a poignant ambiguity in Sophie Varin’s painting, an ambiguity between private and public, comfort and discomfort, in and out. The fluffy surface of clean cotton bears bloody subjects; the shady interior is made public through painting, the cosiness is made gone. For Oedipa in the The Crying of Lot 49, the ambiguity is to come across unwanted miniatures, a series of black swan events happening before her eyes, steadily increasing till they fold back into mystery; they would reveal a conspiracy, should there be one.

Sophie Varin’s own detective novel The Best Intentions of J.P Gutti has a wonderful passage that hints at ambiguity and unresolved patterns: “’J.P is looking down at the marble-print table again, pushing his thumb on the detached piece of plastic in the corner. His eyes are looking at the print but they are not seeing it. He’s picturing something else, something that is neither a print, nor a weak piece of plastic.” Here we read that the marble is fake, it exists and doesn’t at once; it prompts some thoughts in the protagonist, and confuses the reader at the same time.

Like glimpses into something other, whether the mind of a long dead medieval scribe, obscure events in the life of Pynchon’s characters, ambiguous patterns, or nothing at all, Sophie Varin’s miniatures are truly uncanny artworks, painted doors that scratch the surface of politeness we’ve been mentioning all along, or have we.

November 17, 2022