Peter Saul and the importance of having a salary (an interview)

On occasion of his retrospective exhibition at the New Museum we met with Peter Saul, who told us how freedom made him the artist that he has become.

A radical American artist who mixes social issues with pop culture to make trippy, psychological paintings, Peter Saul has been identified with Pop Art, Funk Art and The Hairy Who, simply because his first art dealer, Allan Frumkin, was based in Chicago (as another great art dealer, Richard Feigen – here is a link to our interview with him). Receiving a generous stipend from Frumkin for 30 years, Saul painted whatever he wanted, which is why his work is now so widely embraced. On the even of his New Museum retrospective, the 85-year-old artist sat down with Conceptual Fine Arts to discuss his lucky life and direct, instinctive style for making his highly controversial art.

When did you decide that you wanted to be an artist?

Peter Saul: Around age 15 to 17, when I decided that I didn’t want to have to go downtown and work in an office.

How did you manage to get your career going in Europe, when you lived in Paris from 1958 to 1962 and then in Rome from ’62 to ‘64?

Peter Saul: It was very difficult. It seemed hopeless. I didn’t know what to do and no one else knew either. I only had contact with five or six Americans and they were completely unknown then and now. I made an effort to look around and saw some of Roberto Matta’s drawings at the Galerie du Dragon in Paris. I thought that if he saw my work he would find some similarity, but I didn’t actually know anything about him as I’d skipped art history. Back in Saint Louis my teacher said if you don’t show up I’ll give you a B because I don’t want anyone smirking in the back of the room. I got Matta’s address and phone number from an American artist who knew him and sent him some drawings, but nothing happened. Finally, I got the courage to phone him and he said go quickly to the Hotel Lutetia and see the art dealer Allan Frumkin, who had galleries in Chicago and New York, and tell him that I sent you. I went there and he looked at my drawings and said, Let’s do business. What do you want for them? I said $15 bucks and he said I can do $25. At that time the monthly wage in Paris was about $200 for a working man, so because he continued to buy and support me I basically had no more problems.

Were you showing often enough to get known and selling enough work to survive?

Peter Saul: Yes, within days or weeks of Frumkin buying my work I landed a gallery in Paris. The American artist James Bishop, who had been a roommate in Saint Louis, walked into the Galerie Breteau and the owner asked him what’s new and he said have you seen the American kid who paints iceboxes and suitcases and she said no, where is he? She drove out to see me and arranged for a show right away. Suddenly I had two art galleries, even though I still knew absolutely nothing about the art world.

But you were lucky, right?

Peter Saul: Very lucky—luck played a role in it. Frumkin soon started giving me a stipend and showed my work for the next 30 years. I’ve been lucky all my life, but I hope I’m not going to pay for it with some huge disease, if you know what I mean.

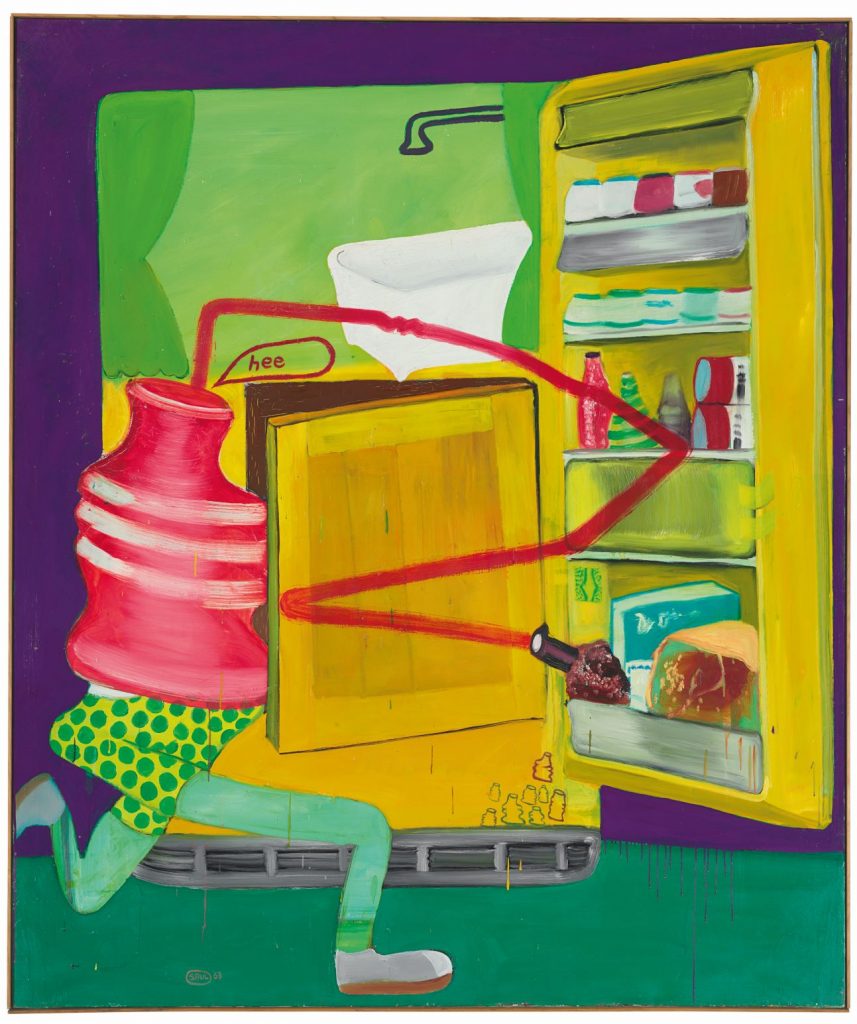

How did you start making the Icebox paintings, which are some of the earliest works in the New Museum show?

Peter Saul: I had seen some icebox ads in Life Magazine, but when it I decided to use it as a form to hold a variety images I couldn’t find any ads to reference so I just imagined how it should look, until I found a picture of one. I made about nine of these paintings over the next few years and put all kinds of things into them—food and cigarettes and furniture.

These paintings and your paintings from the same period with cartoon characters were later seen as a precursor to Pop Art. Did you see them that way?

Peter Saul: No, I didn’t know about Pop Art and I was pretty upset when I read about it because I was hoping that this was only my idea. It turned out that there were a lot of people around the world that came to it at about the same time, which I guess is normal.

How did you get to this place in Paris and Rome, while the movement had its start in New York?

Peter Saul: I never paid any attention to what was going on in New York. I had a fear of flying due to just missing going on a plane that crashed in 1956—the first mid-air collision. But the idea of what you call Pop Art just came to me because I wanted something to put into my Abstract Expressionist pictures. I recognized that I was making a huge compromise, but I had to make a living. I only had $300 left when I arrived in Paris. I realized that I needed to hit on something within a matter of two or three months. I needed something to interrupt the Abstract Expressionism. First I just put in stuff and then I got this idea from Mad magazine that you could tell a story with pictures, which no art was doing at the time—except for the work being made by really bad artists, like Salvador Dali and Norman Rockwell. I sat in the Dome Café, smoked Gauloise cigarettes and came up with these ideas, with most of it coming from memory.

Your work has also been labeled as Surrealism, Funk Art and related to the Hairy Who, just because your gallery was based in Chicago. Are you comfortable with these labels?

Peter Saul: Not really, but I don’t mind them as much now. At first I thought, Oh, oh, I won’t get anywhere now. I’ll just be forgotten, but it worked out okay. I don’t really care anymore.

You often talk about imagination and psychology as being key factors in your work. What role do they play in the conception and execution of your paintings?

Peter Saul: Well, I make the whole thing up—zero research. However, I have a pile of photographs, approximately a quarter inch thick—Ronald Reagan is in there and people like Bush; there’s some piece of pie and pieces of food; some mountains, the Alps behind the Whiskey bottle—but if I don’t find what I’m looking for a about five minutes I just make it up. In fact, I almost always make it up. I’m almost never actually forced to find a photo, and it just irritates me when I am.

And what about the psychology?

Peter Saul: Oh, that’s tremendously important. To me it’s like color and form. By psychology I mean content—the story, what’s really happening. I just love that. Without it I don’t know how people can stay interested in art but they do, yet I don’t know how they do it.

After the Icebox series you made a number of paintings about crime and people being fried in the electric chair. What led you to this gloomy subject matter?

Peter Saul: Well, I didn’t think it was gloomy. Realistically, I’m making use of these things. The person in the electric chair is more interesting to look at than a person reading the newspaper—so I chose the electric chair. Before World War II, it was headline news: Joe Fries in Chair.

Were you attracted to stories about crime?

Peter Saul: Oh, yes, when I went out the door to go to school as a kid in San Francisco I looked out at the bay and Alcatraz was right there, with Al Capone in it, and the children of the guards went to school with me. Bloodshed was a big deal.

Are you interested in social injustice?

Peter Saul: If I can make use of it in my pictures, yeah. I agree one hundred percent with something that I read by the art historian Harold Rosenberg: Politics can help art, but art can’t help it. I sort of agree with him. I think anyone that’s influenced by a painting must be insane.

Were you protesting against the Vietnam War when you made work about it, like the painting Saigon, which portrayed American soldiers torturing and raping Vietnamese women, in 1967?

Peter Saul: What goes into that—first of all—is the urge for exaggeration. I had no idea of what was going on in Vietnam. I was living in a 100% liberal community in the Bay Area. I never even socialized with anyone who was in favor of the war. I did take part in a protest once, and people were beaten to the ground all around me. No one touched me. I must have looked like an FBI agent, with a necktie and sport coat. I was hoping my paintings would be more leftist than they were. I let the psychology run away with it. If I saw a possibility for something really interesting to occur in the painting I let it happen, no matter if it was fascist or anything else. Just let it happen! Frumkin—my sole customer and backer—was probably pleased by that attitude. Also I wanted, for reasons of pure egotism, to have this kind of art to be as far over the top as Donald Judd and the other kind of art was. You had Larry Bell with his glass boxes making a different kind of Rodin. Why not? Therefore, I can do the same. I wanted it to be over the top. The weak point of politics in art is that it’s toned down so that you can agree with it, which is an obvious collapse of the thing. It’s also the reason why I had so much trouble, but not now. My art is expected to be extreme now.

In past interviews you’ve said that lack of maturity is your art style and that even though you are in your 80s, when you paint you’re a 15-year-old. How does this juvenile approach impact your paintings?

Peter Saul: Well, it’s a boast, but I actually am 85. But I hope that approach impacts my work. I don’t want to express a maturity in art. It’s not good for the kind of work I’m making. The kind of thing I’m doing is better off if it’s immature.

Does it keep your work edgy and interesting?

Peter Saul: To me it does, yes. To be interesting is one of my goals; it’s a big one.

Do you see yourself as a rebel?

Peter Saul: Hopefully, yes.

Do you have a cause?

Peter Saul: No, my cause is my own well being.

Do you find joy in portraying angst?

Peter Saul: Yeah, it’s a more noticeable psychology than being happy. There’s happy all over the place, but the amount of visual angst is less, so I go for it.

Like a Wall Street guy blowing his brains out.

Peter Saul: Yeah, that’s good. His happiness is less interesting to look at. It’s more interesting when his life falls apart.

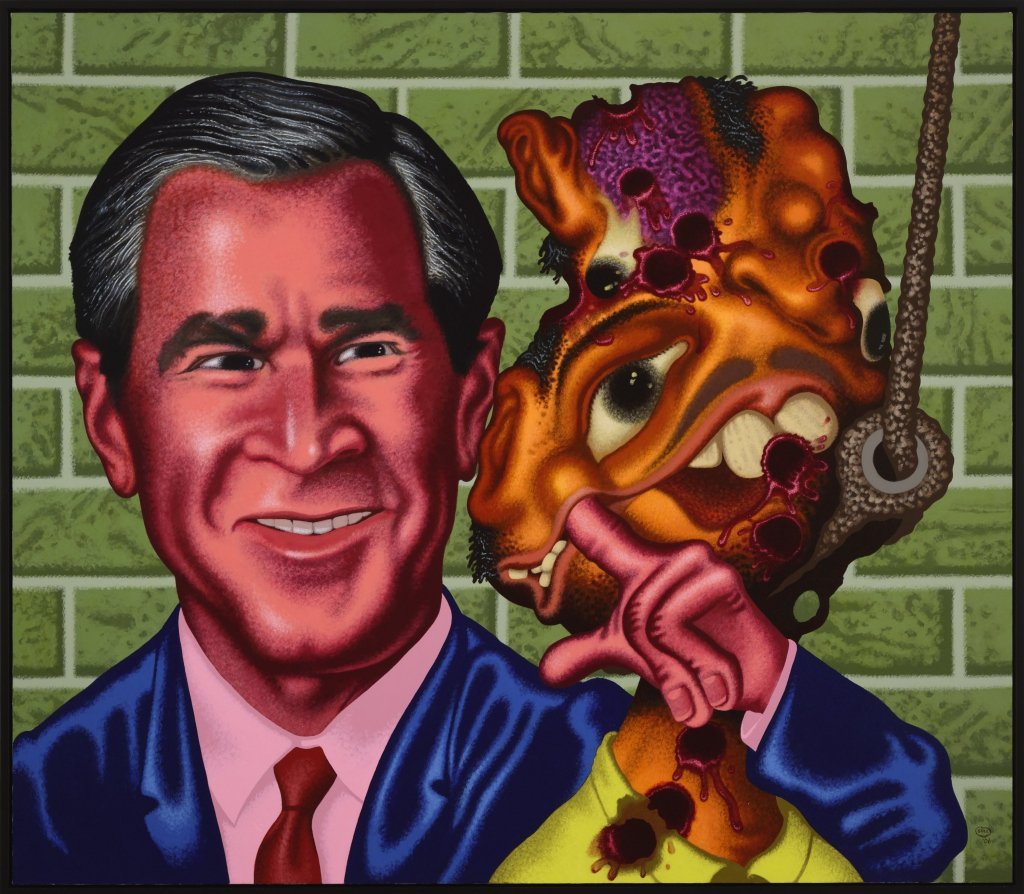

What role has ridicule played in your psychotic pictures of celebrities and politicians?

Peter Saul: Gee, well I just shamelessly put the psychology on to these people without knowing them. I’m not out to ridicule them; I’m out to use them for my art style. My art style says: Need a celebrity, who do we have today? Someone who heads a museum or someone who has an army—a human being who is well known. I avoid anonymous people, unless they’re doing something sensational.

Are you a fan boy of these celebrities or a hater?

Peter Saul: Neither one, really. They’re just there as subject matter, like a still life. I’m not a fan of things in still lives.

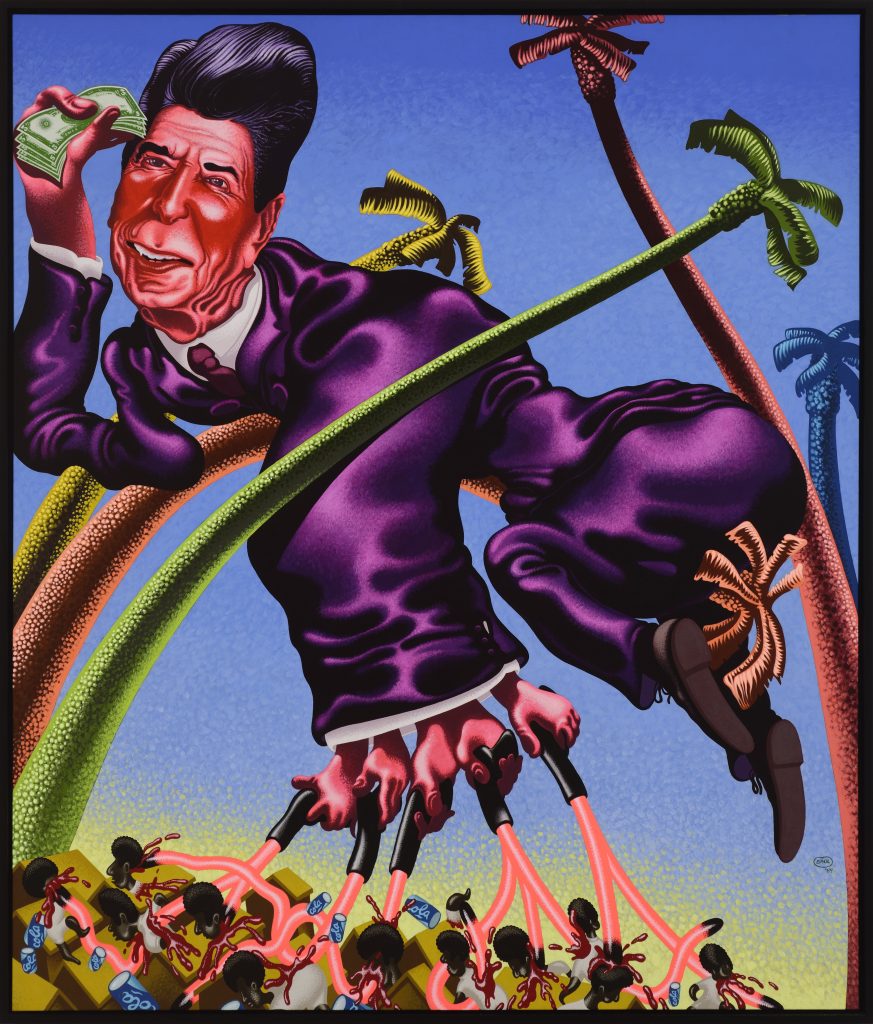

But if you depict Reagan as a villain.

Peter Saul: Oh, he’s my favorite. He’s so good because he suits my art style—his shape, his hair, everything about him suits my art style. He’s a good guy for art—terrible otherwise.

You’ve painted Hitler, Stalin, Nixon, Reagan, Bush, and Trump as demons, villains and lunatics. Why did you pick on them and not other leaders like Churchill or Obama?

Peter Saul: I don’t seem to have the same urge to paint good guys. It’s just my own fault, but I’ve tried to do the right thing once or twice in my 80 years.

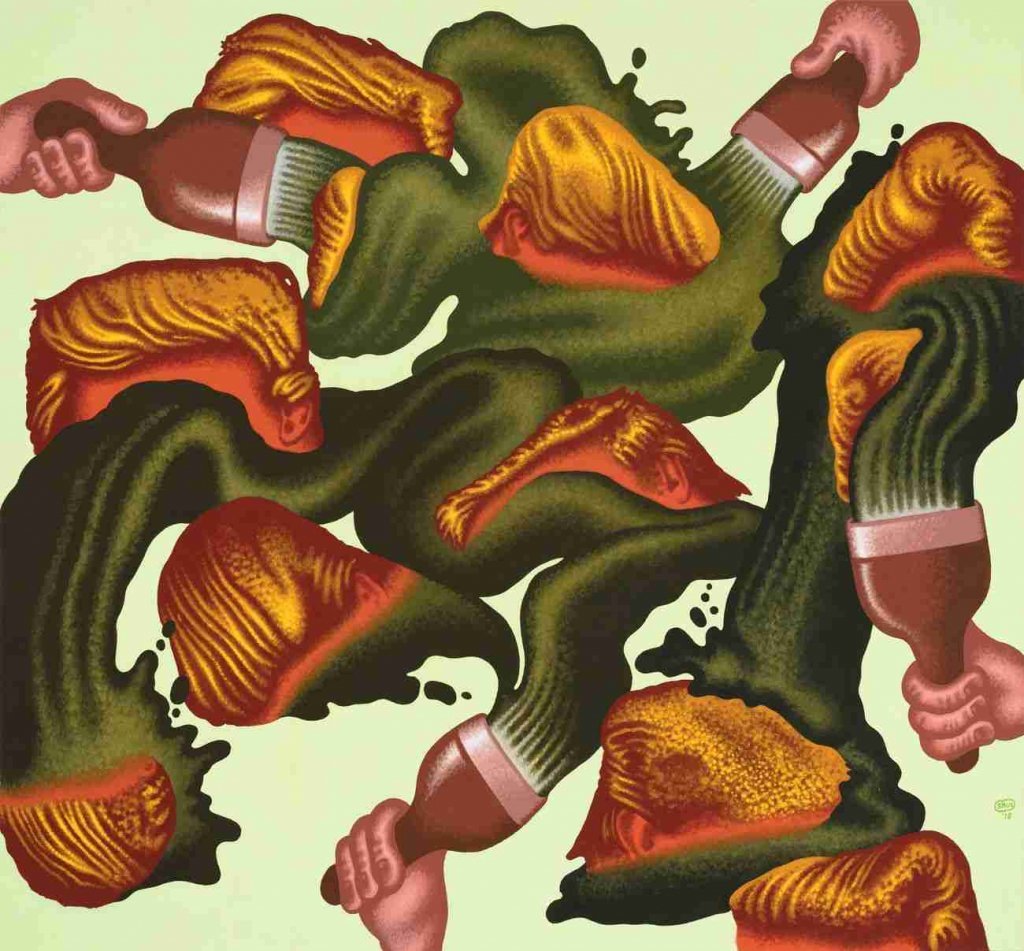

In the 2018 painting Abstract Expressionist Portrait of Donald Trump, which just shows his orange coif and a bunch of hands wielding paint brushes engaged in mark-making, are you mocking this president or the art movement?

Peter Saul: Holy Moly! I’m just trying to make use of this art movement. I don’t mind it that much. I’ve never thought of myself of a follower of art movements. I just use them like art supplies. Cubism is a useful art movement, too. My question is always, is it useful to the picture I’m painting? Does it help the thing to be drawn? I’m in favor of art movements that are helpful. The best one is Surrealism, of course, but not the actual art movement itself—just the idea of loony psychology is what I like.

And when you first lived in New York in the late 1970s you made a series of subway paintings that showed white cops killing blacks and Hispanics and black cops killing white folks. What were you trying to convey about the city in that moment?

Peter Saul: Chaos and danger—there were huge complaints at that time, just like now. I wanted to freshen up the picture, so I tended to have black cops kill white wrong doers in the worst ways, and vice-versa. I definitely wanted to avoid any yawns, which comes from the usual complaints.

What’s your attraction to brutality?

Peter Saul: Uh, oh. It’s visually possible. It’s something people can do. I just finished a painting called Lip Wrestling, which I had hoped would be about kissing but I wasn’t able to draw it very well so it ended up being lip wrestling. What a bummer!

Are you holding up a mirror to our culture?

Peter Saul: I didn’t think I was, but if I have it’s okay. I’m flattered at the idea. Frankly, I didn’t think as much as I’m credited as having thought. My main thought was to paint the picture. Every time I got an idea for a painting I felt lucky and then I got to it. I try not to question it. I know from having taught school that most people do too much thinking. They often talk themselves out of doing anything interesting. There would be good reasons for not doing it.

Do you have any taboos?

Peter Saul: Yes, I do. Several taboos have been given to me by my wife Sally. One is 9/11, when the airplanes crashed into the towers. I’m not supposed to do anything on that subject. I promised her that I wouldn’t do it, even though I had made a little drawing, but that’s as far as I got.

In nearly all of your works—dating back to even the earliest ones—you’ve depicted people and objects as morphing figures and things melting into one another, which makes me think of something like Max Fleischer animated cartoons of the 1930s and ‘40s. How did you develop this style and what were the influences for it?

Peter Saul: The comics Plastic Man was obviously a big influence, and also Crime Does Not Pay comics. I never stopped being influenced by these things. There’s a much more recent comic that fascinates me, called Trailer Trash, out of Boston, in the ‘80s or’90s. And the underground painter Robert Williams, who never gets enough credit. I met him once for five minutes and never saw him again. He’s very good at picturing stories. I also like Robert Crumb.

You taught in Austin—far from the center of the art world—for nearly 20 years. Did you feel like you were working in isolation, even though you were showing in New York, and did it benefit your work?

Peter Saul: Actually, it was the best time in my life. I really enjoyed myself, but that was because I had a happy family life and easy work. I never left my house until the class had begun. I never learned anyone’s name; I just said do it. I thought the whole picture was to do it by itself and if the artist had to show up at all it was a pathetic sign of weakness. If you needed someone to speak, like an art critic it was a no-no. I wanted my art to do everything that needs to be done, which is crazy nonsense.

In the New Museum’s catalog interview with Massimiliano Gioni and Gary Carrion-Murayari you state “One of my great strengths is that I care little about what people think of my pictures. How has that been a plus in your art making?

Peter Saul: Yes, that’s true. It’s been a big advantage. You can do anything you want, which I’ve taken full advantage of and show off all the time—kind of like bodybuilders who wear really tight clothes so you can see the muscles. I do that, too. I deliberately do things other artists wouldn’t do. The biggest weakness of the artists that I’ve met in school is that they worry about selling things. If you are worried about someone putting it in the living room, you can’t do very much.

Do you think your isolation had anything to do with the greater art world taking so long to catch on to your work?

Peter Saul: When I retired from the job in Austin and we moved to New York it was a huge plus. I didn’t realize how important it was. I think that teaching is important for artists. It helps them learn how to speak about art, but I’m not doing such a great job of it now. However, sometimes I do a good job of impersonating myself. When it’s smooth.

If you hadn’t become an artist what do you think you might have been or would be doing now?

Peter Saul: I don’t know. I probably would have been very upset, living in a room somewhere doing practically nothing. I think I had to be an artist.

April 20, 2020