Lucy Stein: Digitalis purpurea, a re(in)trospective

Vieni! E fu molta la dolcezza! molta! / tanta, che, vedi… (l’altra lo stupore / alza degli occhi, e vede ora, ed ascolta / con un suo lungo brivido…) si muore!„

Maria, ricordo quella greve sera.

L’aria soffiava luce di baleni

silenzïosi. M’inoltrai leggiera,

cauta, su per i molli terrapieni

erbosi. I piedi mi tenea la folta

erba. Sorridi? E dirmi sentia, Vieni!

Vieni! E fu molta la dolcezza! molta!

tanta, che, vedi… (l’altra lo stupore

alza degli occhi, e vede ora, ed ascolta

con un suo lungo brivido…) si muore!„

from Digitale Purpurea, by Giovanni Pascoli

Ghosts are not always harmless

We come from a time when a lot of attention has been paid to ‘iconic’ painting. This ‘figurative’ wave began in 2015, after the bubble fuelled by baby artists’ auctions burst. At that time Lucy Stein had already been on the scene for some time, after attending the Glasgow School of Arts (between 2001 and 2004), and De Ateliers in Amsterdam (2004-2006). By means of figurative painting she was already conveying her view of the world, in the way that best suited her need to express the experience. We will shortly come back to this word, which is so crucial for the time we are going through now. There is however another fundamental issue that needs to be clarified first. Visual arts are very different from music, but sometimes one may help to better understand the other. There are many genres of music. Rock, jazz, classical, folk, and so on. Jazz belongs to the second half of the twentieth century, but you can still write an extraordinary jazz song today. And if it is a good song nothing prevents it, even though jazz is not in vogue, from achieving its place in music history. Something like that applies to painting. Expressionism doesn’t start and doesn’t end with the painters of Die Brucke or Fauve, with Emile Nolde or Paula Modersohn-Becker, all art movements and artists to whom Lucy Stein’s work could be traced back – in this regard do refer to this writing which explains how the anchoring effect can also work in arts. These are the founding fathers of expressionism, just as Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, or Duke Ellington are in jazz music. Hasn’t Picasso himself been a very sophisticated expressionist during his whole career?

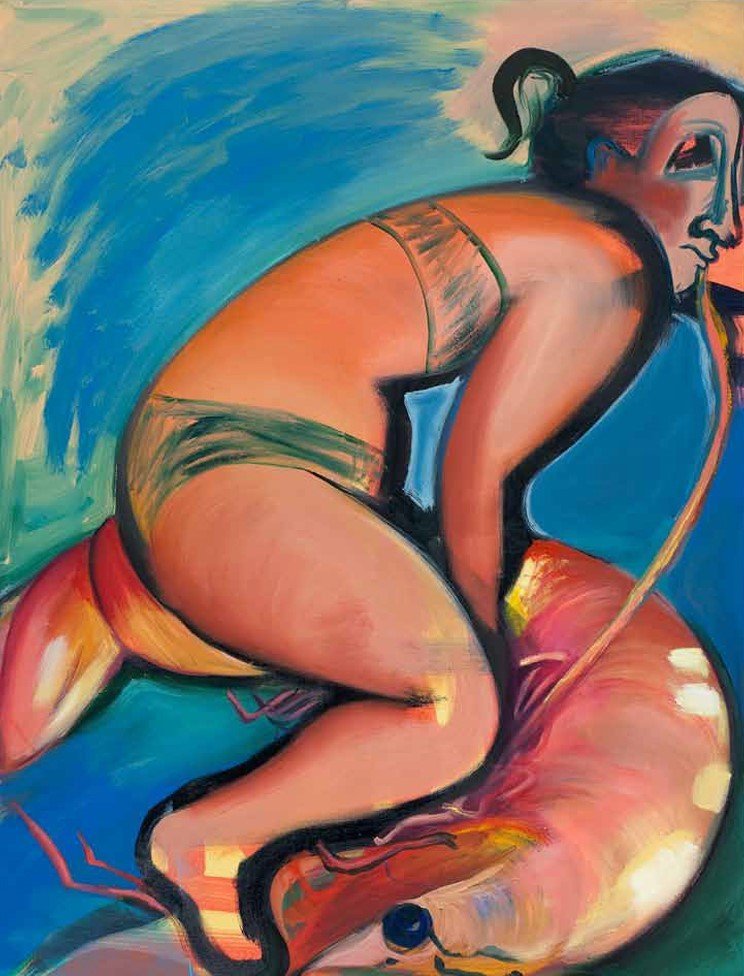

Lucy Stein’s first solo exhibition at Galerie Gregor Staiger in Zurich dates back to Autumn 2011. It is titled The last Bohemian on the Costa Blanca. The previous Summer the artist curates an exhibition in Jesus Pobre, a village in the province of Alicante where the Stein family has had a holiday home since the late 1960s. This exhibition is titled The invincible Summer within. Invited artists are Marlene Dumas, Shana Moulton, France Lise McGurn, Andrew Kerton, Henry Guy, Habima Fuchs, Alex Neilson. The exhibition in Zurich is a ‘visceral’ (Stein) response to that experience, imbued with community spirit and mediterranean joyfulness. The painting entitled Gambas at Pil-Pil is part of it, and is chosen to illustrate the review Quinn Laimer writes for the December issue of Art Forum. Lucy Stein, who was born in Oxford, is 32 years old at the time. The Galerie Staiger opened the year before. A female figure in a bikini leans over a huge red shrimp, which looks very heavy (or is it light because it’s an inflatable?). Pil-Pil is an Andalusian concoction of chili, peppers, parsley and garlic used to season shrimps. The image is enigmatic and evocative at the same time. It looks at the Summer on the Riviera with saturated colors and clearly expressionist black lines; but the artist might want to refer to the inflatable lobsters by Jeff Koons (2003). Or, like these, she might respond to Salvador Dalí, who is calling from Port Lligat, just a little further north. The female figure dominates the shrimp as if instead of a shrimp it were a bull. You could spot a Demoiselle d’Avignon in the woman’s face and right foot – which the black eye of the crustacean stupidly stares at.

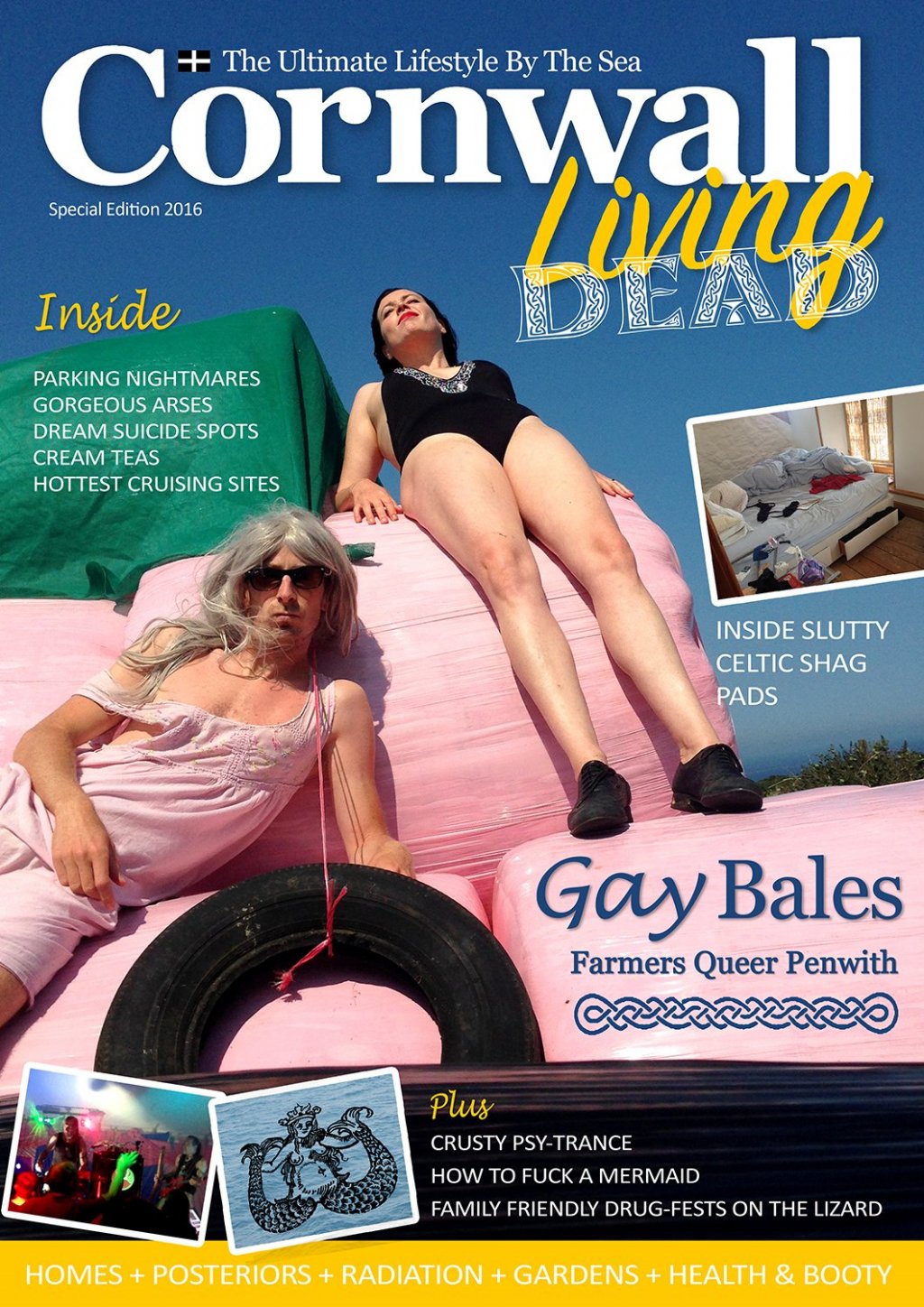

The following year Lucy Stein exhibits at Gimpel Fils in London, where she is asked by the gallery, as customary, to work with a second artist. The exhibition is titled Manderley, like the haunted house around which the story told in Rebecca, a novel by the writer Daphne du Maurier, takes place. Stein chooses to exhibit with Carole Gibbons, who is from Glasgow, but is almost fifty years older than her. Stein had met the artist years earlier in Spain, hanging out and painting with her son, Henry Guy – who then Stein invites to the exhibition in Jesus Pobre. Gibbons enjoys only local fame, but Stein finds in her an anthropological, cultural, and figurative reference – here’s a link to a writing by Lucy Stein about it. Carol Gibbons and Daphne du Maurier could be seen as sort of role models for Lucy Stein; they help her to define her own artistic identity and interests. The lived experience goes hand in hand with the one generated through modernist women’s literature, a fundamental provider of intellectual experiences in her artistic development. Femininity is a standpoint that is often resolved in the theme of duality. Cornwall and Celtic culture are therefore a logical consequence of this approach, as it can be seen in two other works from that period, Where the Celts go to die and The Curse, both executed in 2011. The first is part of a series dedicated to Breton women and marks the moment when Lucy Stein begins to open up to a localism that has inspired many artists, starting from Paul Gauguin.

Lucy Stein, Where the Celts go to die, 2012; oil on panel, cm 50 x 50. Courtesy Private Collection, Switzerland.

Lucy Stein, The curse, 2012; oil on panel, cm 50 x 50. Courtesy Collection Jackie Haliday, London.

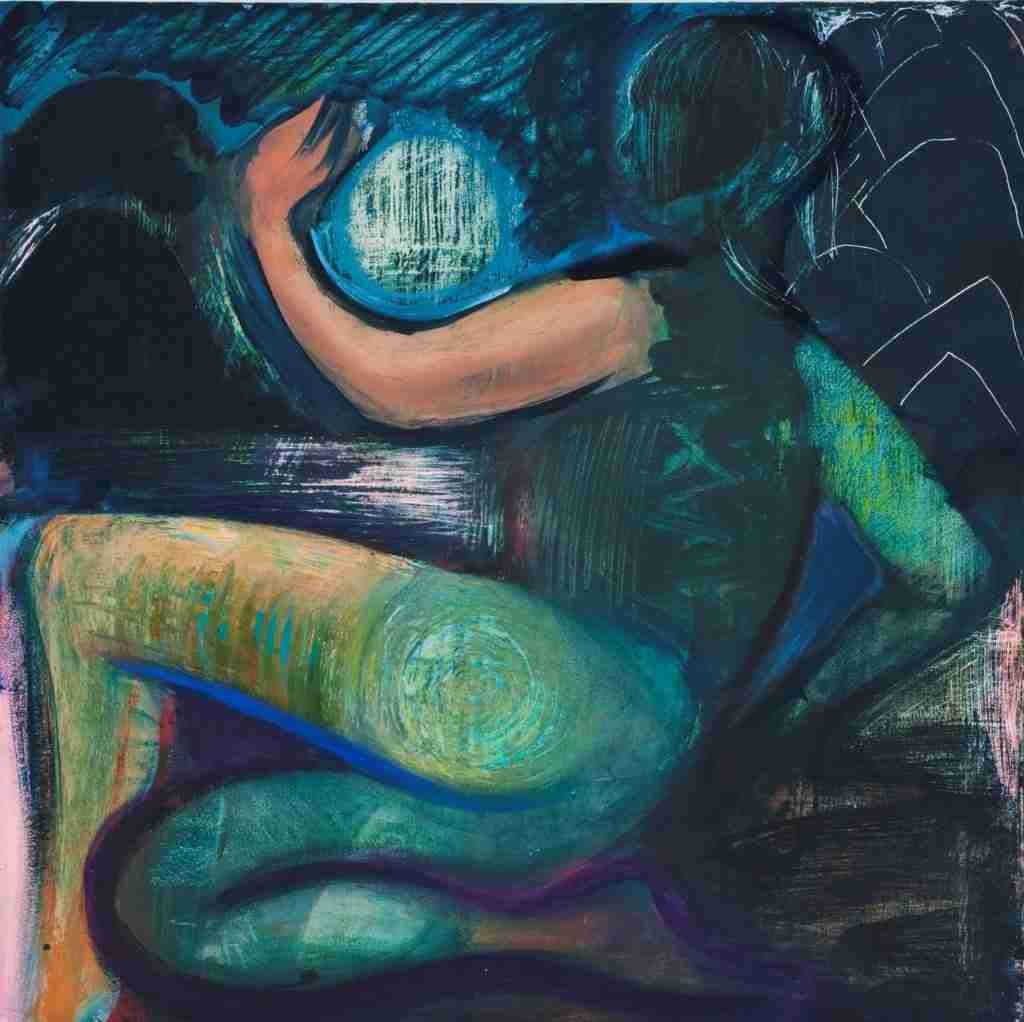

Lucy Stein, Psyche, 2012; oil on panel, cm 50 x 50.

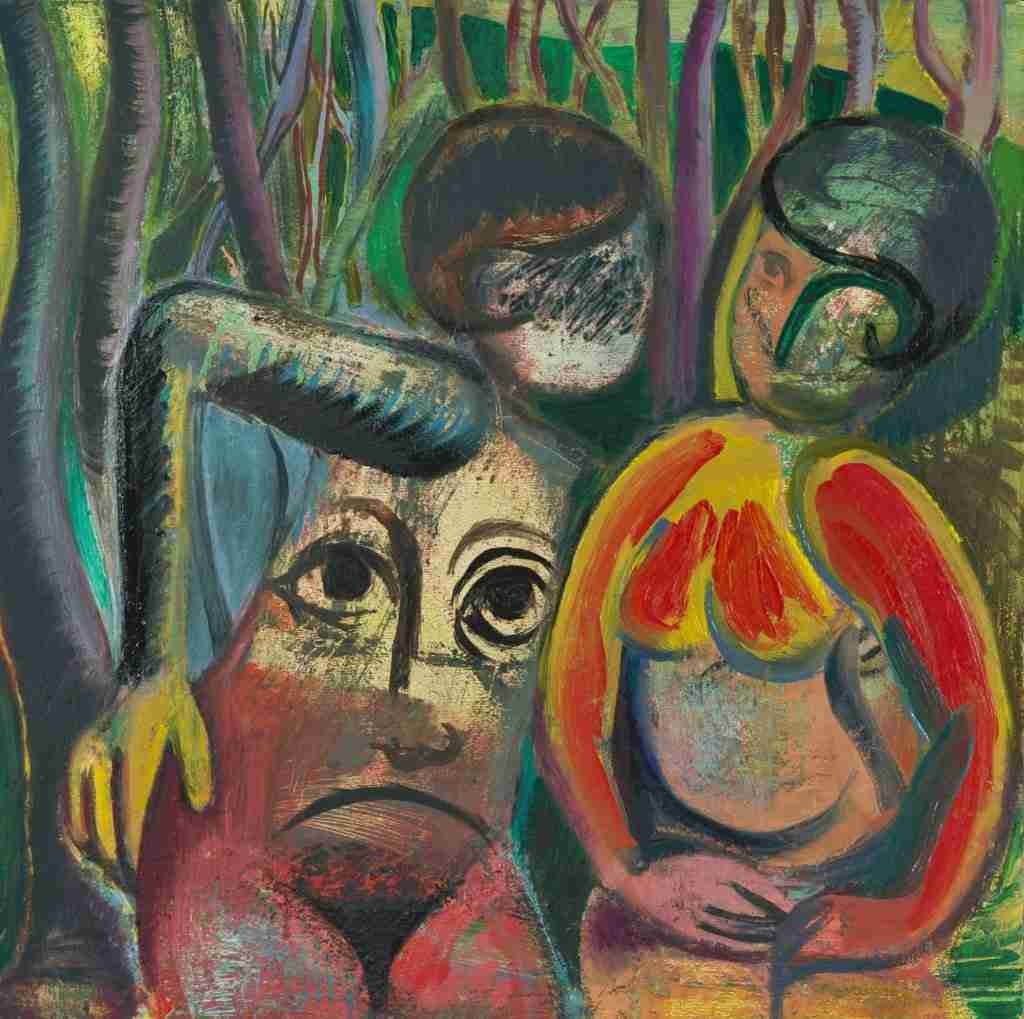

Landscape and figure are part of the same arrangement scheme; they intertwine. The theme of duality also takes shape. The artist represents it from a female point of view in The Curse. The two figures have the same hairstyle, they are part of the same person. One possesses the other. Let’s note the formal similarity between the right leg of the Breton woman and the right arm of the figure on the left in The Curse. The ancestral and mystical spirituality of the Celtic civilization soon becomes a means to investigate the artist’s inner self. And this personal journey continues in Canada, where Lucy Stein goes in 2012 to participate in an artist residency at the Centre for arts and creativity in Banff, near Calgary. Psyche is the result of this experience, when meadows and primitive stones are replaced by mountains. In Canada Lucy Stein meets the Canadian painter Vanessa Disler, with whom she will collaborate in the following years. The painted figure holds the moon in her arm. She seems to be a synthesis of the character depicted in Gambas at Pil-Pii, the Breton woman in Where the Celts go to die and the two figures in The Curse. Interesting to notice is the practice of painting a part of the body as if it belonged to another painting, with a different light. In Psyche it also appears the astral element that returns in the Berries, Lucy Stein paints the following year.

A red painted purfle frames a figure who is apparently acting in a sort of mental theatre. In 2013 Lucy Stein’s second exhibition at Galerie Gregor Staiger takes place. The artist begins to show interest in the theme of fertility and the rural rituals dedicated to it. References to modernism become less evident, while painting grows more instinctive and cheerful. Breath of God is part of a group of works inspired by the myth of Leda and the swan and by the version of it given by Francois Boucher in the mid-eighteenth century. Lucy Stein’s painting has changed. The position of the swan’s beak is cheeky, the female figure offers herself, as in a certain way did also the Breton woman (but not those of Gambas at Pil-Pil and Psyche).

The edge of the blue pool where the scene takes place bears decorative traces similar to those seen in Berries, with which Breath of God also shares the purfle within which the scene is inscribed – at that time the artist is into decorative motifs of nineteenth-century English Pre-Raphaelite movement, and in the decorated borders of embroidery and tapestries from Arts & Crafts. The theme of fertilisation is also found in O!, included as well as Breath of God in Stein’s second solo show at Galerie Gregor Staiger. In this case, however, the open egg is the head of a male character, suffering on a sofa and barely able to hold a leaf. It’s an unarmed and emptied Humpty Dumpty that no one can ‘put back together again’. Like the character in the English nursery rhyme, also the one painted by Lucy Stein is intrusive and fragile. A woman in the background watches over him, hieratic like a Medieval saint. The theme comes back, with new chromatic brightness, in Utopian Tubes, also from 2013. Two huge swans representing the female organ to which the title refers overlook a supine body, naked from the waist down, which another figure watches over. The swans are majestically symmetrical, light and dynamic, separated at the chest by two astronomical elements, the same anthropomorphic planets that appeared in Psyche, and then in Berries. Lucy Stein’s painting has now become a language with recurring structures and subject matters. The winged griffin that pops up on the left in Under a Ginger Moon, painted in 2015, reappears the following year in Bee Cumming at Boscawen’Un.

Lucy Stein, Under a ginger moon, 2015; oil on canvas, cm 180 x 160. Courtesy Private Collection, Zurich.

Lucy Stein, Bee Cumming at Boscawen’Un, 2017; oil, oil stick, pastel, spray paint and magic marker on canvas, cm 180 x 160. Courtesy Private Collection, Switzerland.

This element refers to a Medieval manuscript, which becomes a source of experience, just like the others encountered so far. Among these, Celtic culture and modernist women’s literature continue to play a role. The authors who mark Lucy Stein’s path are Jean Rhys, Doris Lessing, Clarice Lispector, Djuna Barnes, Sylvia Plath, Virginia Woolf. To this latter Lucy Stein dedicates a series of works which will be part of a collective exhibition, Virginia Woolf – An exhibition inspired by her writings (Tate St. Ives, Pallant House, the Fitzwilliam Museum, 2018). In the case of Under a Ginger Moon, one of the few monochromes painted by the artist, it is worth paying attention to the left part of the painting, which plays on the ambiguity between what could be a gallery – an anatomical rather than architectural one – or a big eye – perhaps that of the scowling griffon vulture which holds the dreamy head in its beak? In the background is The Wise Wound, a book dedicated to the many aspects of the menstrual cycle written by Penelope Shuttle and her husband Peter Redgrove in 1978. The book generates a cluster of ideas from which Stein’s third solo show at Galerie Gregor Steiger (Moonblood/Bloodmoon, 2015) stems from. It also gives its title to a performance at Porthmeor Studios in St. Ives, where Lucy Stein takes part at the Tate St Ives Artist Programme.

Lucy Stein, Female knight of the realm leading the red squirrel to certain extinction amongst the English bluebells, 2017; oil, charcoal, oil stick and pencil on canvas, cm 180 x 160. Credit Suisse Collection.

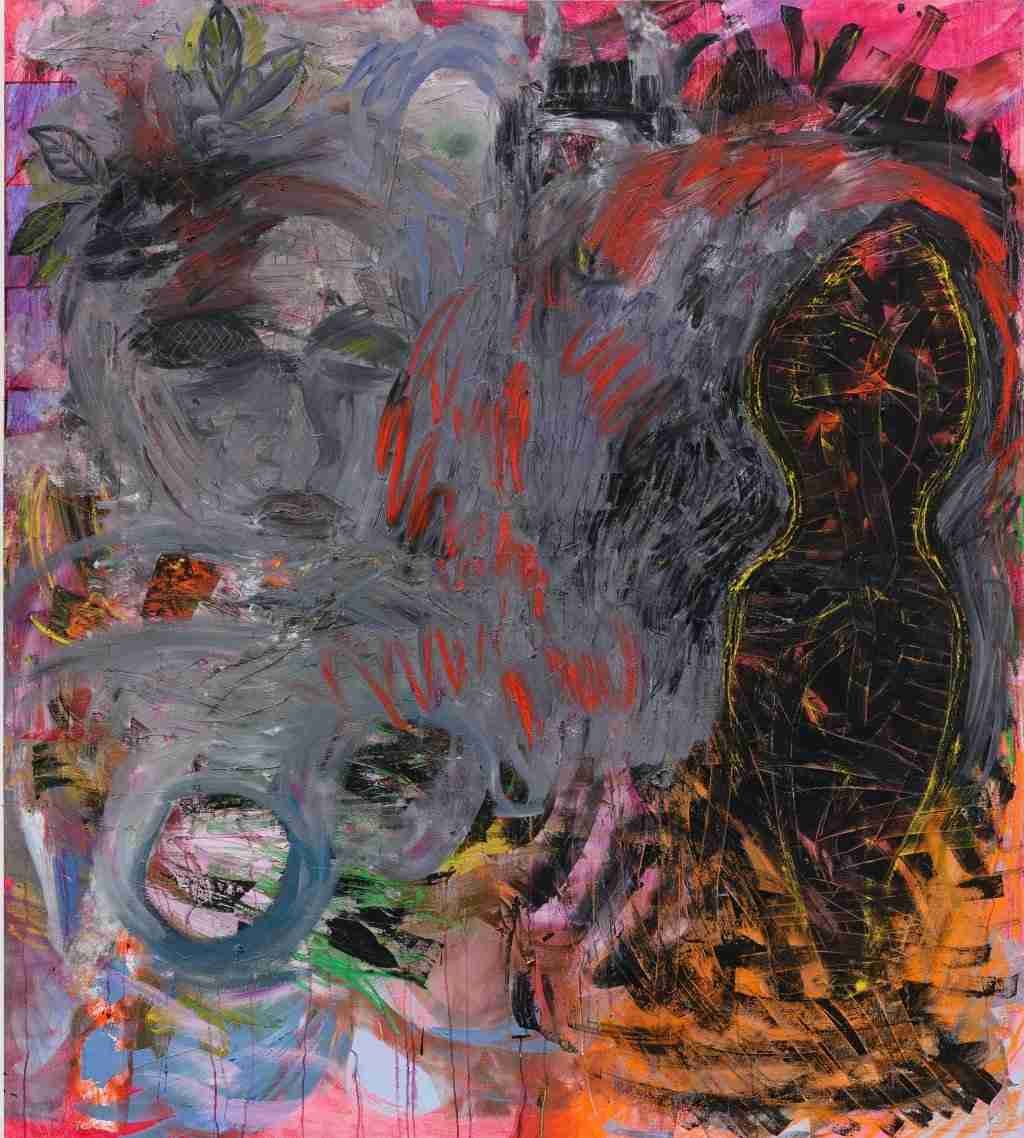

Lucy Stein, Digitalis pussy juices, 2017; oil, oil stick, pastel and charcoal on canvas cm 160 x 180. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich.

The sense of community from which the first group show in Jesus Pobre was born now leads Lucy Stein to look beyond painting, into free jazz and folk music, for example, with the band Death Shanties (see in this regards what the artist says in the below interview). Concerning folk music, Lucy Stein is interested especially in the way that inherited or readymade songs get passed down and altered by different singers, being both very emotional and dispassionate. She is into female singers like Shirley Collins, Anne Briggs, Sandy Denny. There is another figure that recurs in the paintings of this period, that of the sailor. He appears on the right side in Digitalis pussy juices and on the left side in Female knight of the realm, both from 2017. The character, virile and effeminate at the same time, is taken from the celebration of May Day in the town of Padstow, on the north coast of Cornwall. This folk practice reminds sailors and fishermen from this town of their ‘anthropological’ origins. In Female knight of the realm two other interesting elements emerge. The first one is the small two-coloured tiles that the artist introduced in 2015 in her work as ‘archives of personal symbols’ (Stein), which can be placed outside or inside the painting. The work in question contains three of them; their origin is to be found in the small village of Manises, Spain, where the artist studied ceramics. The other vernacular element, in the upper part of the painting by the sailor’s forehead, is the stone circle from Boscawen’Un, near St Buryan, in western Cornwall. The artist’s fascination for this place returns in Bee Cumming at Boscawen’Un, a painting describing the mystical experience of being at midday at the centre of this magical circle, crossed by erotic, esoteric, folk energies, with the griffon vulture holding in its beak the head of a female figure beside which a pagan female deity is represented.

This vision, that at different times would have immediately called into play the thousand doors of perception and their keys, that allows us to come back to the question that we posed at the outset while looking at Cosmic Knockers – the guiding work of the fourth solo show at Galerie Gregor Steiger, in 2018. Lucy Stein’s work is above all a discourse on cultural identity, which ponders over the importance of ‘roots’ for the individual and the community she belongs to, those same anthropological roots to which, for instance, the Howl’s Moving Castle by Hayao Miyazaki also is dedicated – note the Miyazaki is also an insular artist. This identity is moulded in personal experience, the raw material that the artist then works on. But what happens when the exclusivity of this experience is stolen by a foreign entity, namely a tech corporation, interested in taking commercial or political advantage of it? What is left of human being’s identity? Can the massive mining of personal data end up depriving us of our own and unique experience? Well, we may soon be in need of those cosmic knockers… Those ghosts may begin to really exist, but according to many scholars – John Bellamy Fosters, Julie E. Cohen, Joseph Turow or Shoshana Zuboff just to name a few and point to some important literature about today’s surveillance practices – they would be by no means as harmless as those in the English legends. Note of the artist: “to me ghosts are not always harmless – they are portents of danger and doom and we must sail close to them and take notice of their messages in order to navigate constantly shifting psychological and biological realities!”

Lucy Stein, an interview

As an artist, what do you think you have accomplished up to now, and what do you still want to achieve?

Lucy Stein: I am writing back to you under such a particular, and yet, bizarrely, global set of circumstances, under lockdown due to coronavirus, with a new baby, and a rambunctious toddler, both of whom need constant mothering. So, it is hard to describe who I am as an artist right now despite the fact that this is not distinct from who I am as a parent, wife to a fellow artist, and homeowner. Making art is not on the daily agenda and yet thinking about it, or through it, underpins our household and way of life. It is easier to applaud myself for the fact that I am still going after all these years.

Being an artist always felt like a vocation for me, so in a way every move that I have made to overcome complacency feels like an accomplishment. By that I mean that I had to recognise the privileged conditions that allowed for that feeling of vocation, and not rest on so-called “talent” as talent can greatly threaten a young person’s potential to make good art. At the same time I have also had to work hard to not become a “mediocre caretaker” of my talent (to quote F. Scott Fitzgerald). I suppose you could call it a genius complex. As an art student I was very hard to teach. I had an emotional charge to my work, but reached a comfort zone fairly quickly, and this provided a buffer against whatever intimidated me at the time. Only a handful of tutors could get through to me. Some of my earlier work was lazily personal, despite an emotional earnestness. Some of it was good. So getting beyond myself and my comfort zones has been quite an accomplishment, but so has remaining true to that dark charge. There is a quotidian quality or you could say “pettiness” to the personal which I have tried to retain, even as I get better at making things that contain the feeling of “art” and the universal. I see this as a feminist approach to painting, it goes beyond the subject matter and extends to the messiness of the sides of my paintings. My works are careworn and covered in grubby fingerprints (although you can’t always see this in digital images). I suppose one accomplishment is that, at their best, my paintings can demonstrate paradoxical thinking in motion. Probably my main accomplishment has been to keep on making paintings that, for better or worse, have a numinous power to them.

There is so much left to accomplish. I’m aware that my work tends to be more popular with other artists and writers than with curators and I think this is partly because it feels so personal, and also because I have not been generous with identifying and sticking to key themes and therefore it is hard to use my work to illustrate more general ideas. My themes all get swept along in the life project. So I have to get better at explaining my work. Here are some key words: folkmagic, feminist figuration, female orgasm, psychoanalysis, numinous power, esotericism, spirit of place, expressionism, angst, British modernism…

I want to leave behind a coherent body of paintings, texts, kindnesses, positive examples that convey life to the living.

Has the subject matter of your painting been changing over the years?

Lucy Stein: I’ve always painted women, and to some extent female beauty. Like a lot of female painters I’ve tried to suggest a female gaze, often by giving agency to the muse. My figures tend to be imagined characters from the Western canon, perhaps stand-ins for myself, acting out psychological vignettes. I’ve tried to suggest the ambivalence, fear and shame that comes with embodying the body/mind dualism. I have tried to marry awkwardness with harmony in painting as this is how I have felt in the world. I have used painting tropes and techniques to describe complicated psychological atmospheres, often erotic disturbances. This is not unusual, since this is one thing that painting as a discipline and paint as a medium are well suited to. Usually my paintings have been representative of what has been going on in my life. Sometimes their themes related to my mother, or at least were matrilineal, literally or in the V. Woolf way of thinking back through our mothers. Often my figures have been set in a landscape, but the literary or even narrative character of this relation has been more important to me than the figure/ground painting inquiry. Many of my paintings and performance works have been set on headlands, and suicide has been an emblem, due to a family history that obsessed me for decades.

My source material has changed over the years. I used to paint from my head but now I have come to a point where I can use photographs, even a projector, and the paintings still have a potent quality that works for me. I can finally do direct appropriation. In 2010 I had what I pompously call my “Celtic epiphany” when I moved to the west coast of Ireland, and since then I have been possessed by the fantasies of the Celtic realm, with its folklore and mysticism and potential for mythical transformation. This opened up lots of possibilities in terms of what to paint. I’ve made work from this research for ten years and been fully situated within the fantasy, living and working in St Just in West Cornwall for five years. I have also had five years of intensive psychoanalysis, which has allowed me more space to unpick my dreams and obsessions.

As well as being my normal life, I consider my time living here in St Just as an embodied investigation into esotericism and landscape. As the life/project goes on I’ve become interested in what drives women’s recourse to magical practice and ritual expression. This goes back to my earlier work which looked at cognitive dissonance and a girl’s recourse to self medication which can also be seen as a form of ritual expression.

Is there any artist whose life has inspired or still inspires you?

Lucy Stein: Carole Gibbons from Glasgow is a great painter, a vivid and inspirational character, and, in how she’s been left out by the establishment, a cautionary tale.

How would you describe your studio?

Lucy Stein: I work in Newlyn which is six miles drive across the moors from my home in St Just. (I would prefer to cycle but the road is treacherous.) I work in an old primary school, up a steep hill from one of the busiest fishing harbours in Britain. It is a very picturesque working town where painting and fishing have coexisted for centuries. I took over the studio about three years ago from Rose Hilton the painter (and widow of painter Roger Hilton). She sadly died last year. Prior to Rose the Iranian painter Partou Zia had the studio. I am one in a strong lineage of female figurative painters. I feel like a custodian of this great space, but also very at home in it. I am usually like that in studios, when they work they become like another skin. When they don’t work I destroy them.

Windows take up two sides of the room, which is huge with very high ceilings. One side looks down to the sea although I’d have to stand on the table to see it. The other windows are overlooked by my dear friends and collaborators the artists Nina Royle and Simon Bayliss, who are currently living at Nina’s mum Dominique’s house. Nina previously lived with us for some years. The Turkish artist Ilker Cinarel works across the hall. We are all good friends.

The studio is very beautiful. There is a wood burner and a big storage space that the trust who run the space put in for me a year ago. There’s a sofa with a Welsh blanket my mum gave me. At the beginning and end of both my pregnancies I’ve slept on it a lot. Once a week Jarvis comes and cleans up after me and helps me keep on top of things. Jarvis appeared out of nowhere about a year and a half ago, and he is a godsend.

Since I had Mary May in 2018 I usually run in, work without stopping and rush out. I haven’t been in since having Sylvia since she’s only a few weeks old and we are under lockdown anyway. Lochia and lockdown.

I don’t listen to much except BBC radio 4 and occasional audio books. I used to listen to folk music all the time but it is too sad at the moment. I’m at a loss about what to listen to now. Krautrock can be good in the studio. I prefer silence at the moment.

How do performances, music and moving image relates to your painting practice?

Lucy Stein: My performance events are occasional and very inspired! They can only happen if I am in intense relationships with other artists and I’ve been given an opportunity to expand into something with money and support, and the specific variables are begging to be activated. I try not to put them on for the sake of it, to supplement an exhibition or get people to come to something. I’ll only do a performance event if I’m creating something in it, such as a live painting or reading, or it offers people whose work I love a space to do what they do anyway. I often look at documentation of people prancing around in costumes activating someone else’s work and think “poor sods.” I like the events I organise to be understated and deeply unsettling. I am very psychic so usually they work out well and the atmosphere is steered correctly, but sometimes they can get a bit shambolic. At the moment I am totally wrapped up with my babies and the sort of performances I like to make are unimaginable as the emotional space they try to reach is dark and a bit mad. They might scare the babies. Having said that I’ve been watching a lot of the Cbeebies shows “In the night garden” and “Teletubbies” lately… pure genius, and quite eery. Children are so sophisticated really.

Some of the key performance events of the last five years have been related to the seasons, either directly or jokingly. For example with my friend Mark Harwood I organised something at Cafe Oto in London in August in the blazing heat which wove itself around the suggestion of a christmas depression. I often try to reinterpret agricultural folk traditions as a way of generating and harvesting complex atmospheres.

In the performances and paintings I hope to convey an emotional charge, a peeling back of the layers of reality, an uncanny sense of historical context, a recognition of received wisdom as gut reaction and vice versa… ultimately a revealing of the human being as subject to numerous forces that are playing on us all at once. A tearing of the veil. A clifftop catharsis. A ritualistic and feminist redressing of the linear canon (phallus). All of this is asking a lot, but psychoanalysis has helped me to believe with even more certainty that the personal is political.

The videos that I have made – “Polventon” with Shana Moulton and “Regression” with Simon Bayliss, were ways of working through stuff that couldn’t be realised in any other way. These works are full of ideas. For “Regression” we got past life regressed by a hypnotherapist in a fougou which is a type of prehistoric chamber that only exists in West Cornwall. We worked with the legendary Falmouth band Zetan Spore for a psytrance soundtrack. I felt like I’d taken acid and went into a very serious depression for about six weeks afterwards . A lot of glimpses of ideas come to me in dreams, including the girl riding the prawn in Gambas al Pil Pil. One of the first motives for making “Polventon” was a dream where this goth girl called Gethsemane spoke to me in the living room of the house my grandfather built and committed suicide at which is called Polventon and is further down the coast in North Cornwall. Cornwall is synonymous with psyche for so many people. It’s inescapable, like a parent.

Cover of the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic journal, 2020.

Lucy Stein, Pale fire, 2019; glazed biscuit ceramic tiles, cm 75 x 60. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich.

Are you still collaborating with the Death Shanties band? How has this side of your work been evolving during the years?

No, I don’t do that anymore. I do have some ideas for acetate and light box works for a project I’m working on with Sarah Hartnett in which we travel along the Mary ley Line that runs across southern England. A ley line can be a lot of things to a lot of people, but they appeal to us as energy channels where it is easier to lift the veil. A lot of the source material I used for the Death Shanties performances came from travelling across the UK visiting ancient sites, old churches, country houses and landscaped gardens etc. I printed a lot of heritage paraphernalia onto acetates then made collages and live paintings with this material on to a light box whilst the musicians improvised. Sarah and I are collecting bits and bobs on our journey along the ley line too, and they will feed into paintings and performances at various institutions along the way, ending at Great Yarmouth on May 8th 2022 (if we are still alive then). All my projects feed into each other.

What role does painting play in our society?

Lucy Stein: My own relationship to painting has always acknowledged an element of art therapy, which I think is fine as long as it’s not all there is. Thinking through painting from here in West Cornwall at this point in my life is very different to what it was like at other points, when I was living in Amsterdam, Berlin, Glasgow or London. Not to mention the current context – the public and private emergencies of the virus and the baby. You couldn’t make it up: our newly elected Thatcherite prime minister proclaiming that there is such a thing as society after all, from his sick bed. I think the reason I’ve been struggling to answer this question is because I can’t see what society is or might be at present.

It is easier to talk about cultures. Here in West Cornwall there is a culture of devotion to British modernist painting and sculpture with Tate St Ives as its place of worship. It is both laughably old fashioned – old white skinned white haired codgers in berets, ladies with flowing velvet skirts and scarves and kohl eyes – and totally admirable and inspiring.The palliative effect of a beloved and portable painting object takes on a new dimension at a time where this generation are dying alone in hospitals with only inanimate things for comfort. There is also this wild esoteric culture here, in which painting co-exists with ritual practice, and there are some very good painters making greetings cards and illustrating grimoires. I have always needed to summon up ghosts and change the texture of reality in order to make any work, so this culture appeals to me. The idea of a regional or parochial pride in painting is also important to me, maybe because I grew up in Oxford which is a literary place with no history of painting to speak of, but I always had this family connection to Cornwall. Here in West Cornwall like in Glasgow, I find myself immersed in what can border on hostile ethno nationalism but here being a painter or artist of any sort gives you a passport to belonging, even with the farmers and fishermen. It’s just what people do here. But it doesn’t have much beneficial effect on society so far as I can tell. The kohl- eyed old ladies are still buying the Daily Mail in the post office and they all carry on voting for our creationist goblin tory mp Derek Thomas. Having said that I suppose a creationist goblin suits the land of Merlin.

I read Isabella Graw or Barry Schwabsky from here explaining a multiplicity of viewpoints and reasons why painting is a success medium and they feel both acutely relevant and slightly muffled. Isabelle Graw talks about vitalism and it is an interesting lens to view these painting positions through. But is successfully illustrating society’s power structures and how they are maintained, the same as playing a role in it? Having power in the art world doesn’t interest me that much. If it did I wouldn’t be living down here, however much I might fancy the idea of myself as a recluse. Of course there are forms of power that come from rejection, some of which are laid out in Martin Herbert’s brilliant book “Tell them I said no.” I think there’s been an “if you can’t beat em join em” attitude building up amongst artists and other sensitive people but maybe that’s going to change now.

The truth is that very few contemporary painters speak to me in a meaningful way and much of the time I am disappointed when I see things in the flesh. Personally I care about surface, lyricism, subtle wit, pathos, knowingness in tackling the unknown, counter-intuitive strokes, timelessness whatever that means … I value experimentation. I love the work of Elizabeth McIntosh, Carole Gibbons, Rita Ackermann,… I love my husband Steve Claydon’s tiny and epic paintings that he made in South Korea at the end of last year. In my ideal society people would be sensitive to these qualities and painting literate but I may just mean initiated into my personal taste and sensibility.

If you could, what is the first thing you would change in the art system?

In the UK it is very simple. I would bring back art lessons in schools again, since they’ve been relegated to an after school activity. I would get rid of tuition fees and bring back grants and de-privatise the universities and art schools. The last decade has unleashed hell on the students and tutors at art schools in the UK. Totalising gentrification of the mind has been achieved with additional paranoia of the not very interesting variety.

Is there any colour or shape that, as a painter, you feel uncomfortable with?

Actually deep Catholic purple. I lived with the artist Nicolas Party in Glasgow about ten years ago, and he once asked me why I always painted with this purple and I hadn’t really realised it, but he was right, and it is ugly as hell.

November 25, 2020