Sylvain Bellenger on the online future of museums

An Interview: Sylvain Bellenger, director of Capodimonte, takes stock of the current situation and predicts the digital future of museums.

Formerly chairmen of the Art Institute of Chicago’s historical collections, Sylvain Bellenger began his mandate as director of the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples in 2015. He was hired in the context of the so-called Franceschini reform, which opened the direction of the most important Italian museums to foreigners.

[here the link to our comment about it. Ed.]

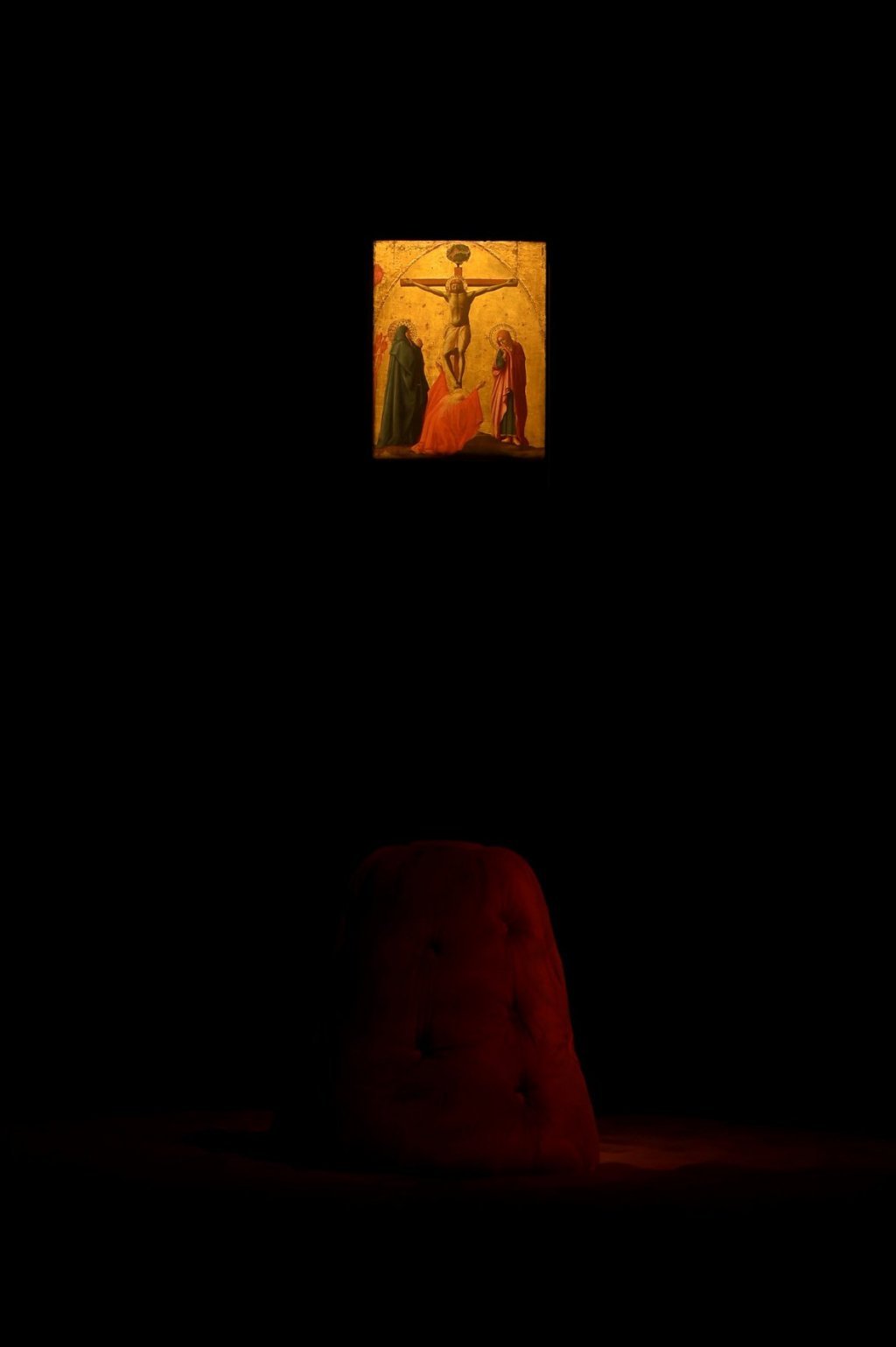

In the last years, Bellenger has managed to give an international breadth to Capodimonte. The intellectual legacy left by the fundamental figure of Raffaele Causa, the former Museum superintendent who died in 1984, greatly inspired his choices. “As Causa said in 1978 during the presentation of the great cretto commissioned to Alberto Burri for Capodimonte, there is no difference between Masaccio and Guido Reni, or between Caravaggio and Burri. They are all part of the story of the human mind” reports Bellenger. Capodimonte is one of the few Italian museums of ancient art to have a significant collection of Modern art too. Artworks from the 20th century coexist next to older masterpieces by Masaccio, Raphael, Rosso Fiorentino, Caravaggio, Artemisia Gentileschi, Titian, Luca Giordano just to name a few. The museum dialogues with the contemporary world as well, for example through projects such as “Carta Bianca a Capodimonte” (Carte Blanche at Capodimonte) in 2018, which brought together 10 unusual curators such as the conductor Riccardo Muti and the landscape architect Paolo Pejrone; or the recent renovation of the Bosco Reale and Santiago Calatrava’s upcoming intervention in the small church of San Gennaro. In this interview, we delve into the ways in which the museum coped with the quarantine, and how it prepares to face the many challenges ahead. As Bellenger says:

“The worst mistake would be to think we can go back to normal”.

What have you learned in the last two months?

Sylvain Bellenger: Only in the future will we know what really happened. For the moment we have learned that when we are confined at home, when the banality of everyday life has suddenly disappeared, our relationship with information, with culture, and with leisure changes substantially. It is no coincidence that cultural institutions, not only museums, have felt the need to communicate about a sense of art of which they are an expression. At the same time, the public demand for culture increases exponentially and people have been looking for this sense online. The views on the website of Capodimonte have more than doubled. Virtual exhibitions have had more visitors than they would have had in the world of material reality.

In the recent years museums have become great exhibition makers, but there are still very few of them investing in their online presence, really exploiting the potential of the medium

[Here is our recent survey on the topic. Ed.]

Do you think the current situation will change this attitude?

Sylvain Bellenger: With regards to Italy, I do not entirely agree with the idea of museums as exhibition makers. I believe that there are fewer museum shows than in other countries, and those that happen often are not really aimed at adding to the discourse on ancient art. There seems to be a larger interest in the form rather than the substance. However I agree with your point about the online presence of museums and cultural institutions at large. The current crisis has accelerated what was already an ongoing process of moving online, which is a subject that needs to be properly discussed. The virtual is not a substitute for reality, but rather a dimension in itself. There is no point in caricaturing a Van Gogh exhibition, or Bach’s music. The online world is much more interesting and sophisticated than that. Moreover, the digital world has already changed the status of images.

How so?

Sylvain Bellenger: Let’s take an example. I’ve recently seen an exhibition of Michelangelo’s drawings at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, which were borrowed from the Teylers Museum in Haarlem. They are compelling small drawings, preparations for major sculptures, paintings and architectural works. The curator of the exhibition [Julian Brooks, ed.] chose to digitally enlarge them to the final size of the object they represent. It is only thanks to these digitally magnified images that I came to understand what it was like to work on a large commission at that time. From this example, I would like to add a further reflection.

Please.

Sylvain Bellenger: Our way of seeing changes with technology. Today we could not see Poussin’s or Caravaggio’s paintings with the lighting of their time. We are somewhat blind. The history of art and attributing artworks to artists have been based on photography. It has altogether changed our relationship with art, and with the raise of digital photography we have been able to look even more differently, I would say even better. For example, let’s think about the details in paintings that are made accessible to anyone thanks to digital photography.

Adding to this, we could say that technologies have multiplied and, just like the internet, they have become media in themselves: from the idea that the medium is the message (M. McLuhan, 1964), every medium rather resembles a language in itself now.

Sylvain Bellenger: This is true. Moreover, the nature of language not only changes the nature of the message, but also its consciousness. It is clear that we will no longer see as we would before the digital revolution. Let me give you another example. These days I am writing about a painting by Matteo di Giovanni titled The Massacre of the Innocents, which was commissioned for a church in Naples. I am studying the work at home with a high definition photograph, and I am finding elements that would have been very difficult to see otherwise. I am discovering the intentions and desires of the painter, and perhaps of the client too, which were not meant to be seen by everyone in the church for which the work was made. We should not forget that the relationship between visible and visual can change through faith, or according to the context, but also thanks to technology. A work of art in a church belongs to a different conversation from the one inside a museum, or on the net.

What is best practice for an online museum experience?

Sylvain Bellenger: To answer this question I would first make clear that for me mere entertainment is not sufficient for a museum experience. I rather look for the possibility of “entering” the work of art through the digital image and related information. On the other hand, we should be wary of when a museum intimidates its visitors by making them feel unable to “see.” The digital medium should give the opportunity even to those without the intellectual tools or expertise to get excited about art. Sometimes it is enough to offer some keys to the reading. More generally, I would say that the online dimension of a museum works when it allows you to go beyond the museum itself. Afterwards, the further you go, the more you want to come back to the museum.

Yet in recent years great resources have been invested in paper catalogs, which are costly, not least for the environment. If culture is not accessible, it does not pass on to the new generations, which now get informed (or misinformed) almost exclusively online. Does it still make sense to entrust knowledge to such inaccessible and elitist medium like the paper catalog?

Sylvain Bellenger: The Conservatory of Music San Pietro a Majella in Naples hosts the largest music library in the world. Yet if it were not digitized, very few could access the knowledge it preserves. Not to mention it is subject to contingencies. A blaze could destroy this knowledge forever.

Is it time to focus on the didactic function of museums instead of understanding them as places of entertainment as we often do these days?

Sylvain Bellenger: Museums shouldn’t make the mistake of thinking they are, or should become, a football team. The audience is different, and so are our goals. But we must also try to reach as many people as possible, without lowering the level of the conversation, or betraying the message that has been entrusted to us. Certain museums, and Capodimonte among them, certainly have an educational and moral responsibility. Museums are therefore not only places of conservation, but they can also become places for thought and debate. In this sense the internet can be an extraordinary tool.

In this regard Capodimonte’s responsibility becomes even greater, since the museum is part of the Bosco Reale, a huge urban park that constantly dialogues and interacts with the museum itself.

This is the main challenge of our Century, a century that will have the greatest responsibility in human history, that is to protect our relationship with Nature and our planet. As Foucault wrote, the garden is the smallest of the worlds, but it is the whole world, because it embodies our way of living together, and our relationship with nature.

May 12, 2020