Emerging artists to watch: Matthieu Haberard

Anything can happen on the threshold, like Matthieu Haberard’s practice, an innocent game of fairy tales, an adventurous story of feats and misfortunes.

Innocent Game and Scenographic Malice

The threshold is an ambiguous place. It can be both a magical site and an abject condition. It is the place where metamorphosis occurs via specific forms of knowledge. Anything can happen on the threshold, like Matthieu Haberard’s practice, an innocent game of fairy tales, an adventurous story of feats and misfortunes. His work challenges our faculties of imagination and visual fluency, until we fully experience a series of ironic fragments of reality. Perception becomes ambivalent on the threshold between mature sarcasm and childish libido.

Strange objects, almost perturbing, activate a sinister and clownish memory. The insomnia and fantasy of the artist participate in this game, producing scraps of dreams, shreds of language, sparks of mystery. Just like the theatrical and cinematographic sets, they are caricatures of complex allegories, masked by phantasmagorical surfaces and bizarre shapes.

Matthieu Haberard uses masks and decorative elements as techniques for awakening and crossing the threshold. His sculptures enact a saga of possibilities. They are stories of latent animism, an ethnography of objects, soliciting reality. Often suspended, they are objects or machines that can’t be turned on, offering potential for activation through the visual malice of the viewer. Their imagery is ambiguous and suspicious, exposing different elements of fantasy and magic that make for a grotesque reality.

This psychic archeology, or an anthropology of things, recalls Walter Benjamin’s interest in the modern survival of the myth. According to the philosopher, archeology is no longer composed of memories and documents. Instead, it is a spectral symptomatology, a debris of something that has become phantasmic and invisible.

Both the spectators and participants of teenage trauma and metropolitan violence are redeemed in Matthieu Haberard’s artworks, which create their own language, elaborating on individual elements for organized organic objects. Play and violence become interchangeable actions in human history. Childhood and maturity reciprocate, and so do innocence and malice.

These topics also resonate in the practice of those artists who sublimated trauma in their work after WWII. They turned the formless universe of outrageous humanity into figures and narratives. For example, many of Matthieu Haberard’s sculptures remind of H.C Westermann’s wood pieces, of the absurdity of Robert Gober’s works, and of Pino Pascali’s Teatrino. The latter especially influenced him. Similarly to Pascali, who portrayed the transition from peasant to industrialized society with his imagination, Haberard contemplates the passage from the pre-internet fantasy universe of Tolkien & co. to the post-internet world of Game of Thrones.

For example, his Les Serpents Naissent à 16 Ans (2018) alludes to the initiation to violence occurring around the age of sixteen. It depicts the symbolic and alchemical figure of the snake, whose skin exploits the same metamorphic and playful artifice found in Pascali’s Bachi da Setola or Vedova Blu. The universe of play and violence also includes medieval imagination, references to which are found in Dans L’Arène (2017), for example. The artist populates his work with armours, mousetraps, music boxes, clockwork devices, sculptures from the stained glass windows of Cluny. It looks as though the Middle Ages lowered a drawbridge to access Western capitalist society, where past visual references are discarded as waste. In this universe, Matthieu Haberard finds the methods to demolish current, post-internet artistic trends. Materials such as wood, plastic and EVA-foam are those of toys. Childhood and games are central to the artist’s aesthetics, again coming close to the playful, rascal character of Pino Pascali:

I only try to do what pleases me. After all, this is the only way that works for me. I don’t think being a sculptor is a tough job. A sculptor just plays, and so does anyone who does what pleases them. Games are not for children only. Everything is a game, isn’t it?

Matthieu Haberard’s sculptures are objects made through play. They owe their existence to a false innocence which, in the form of a puzzling question, stages the malice of art and the virtuosity of fantasy. His series of works À Plusieurs Ça Soulèvent Le Stress feature small painted wooden curtains with elements reminiscent of the stickers that decorate children rooms. The artworks house aluminum engravings alluding to the metaphysics of death through the allegory of the Danse Macabre. In We Love Violence (2019), wooden axes are painted in strident colors. The works Cagna 1 and Cagna 2 (2019) are reminiscent of toy swords, with regal yet ironic grips.

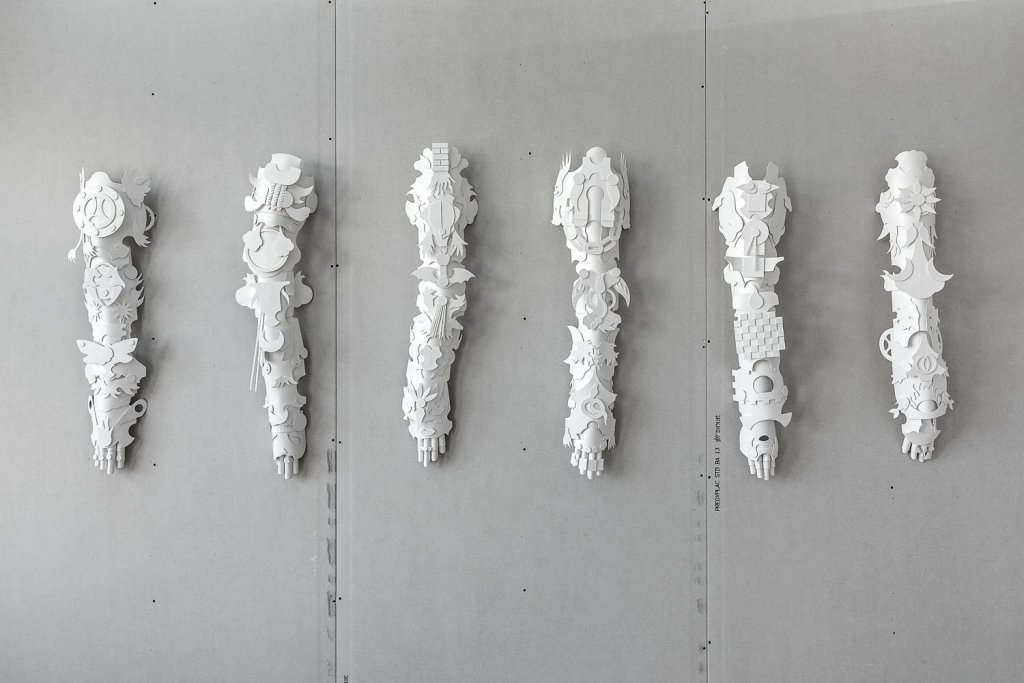

Armors are part of this game too. Inspired by the Chinese and Japanese martial models, their achromatism is defeated by their hyper-decorated surface. Parle (Les Yeux Ouvert), Insomnìe (Fleure), Pas (une Insomnìe) are vestiges of fantastic times and relics of ghost battles. Their scenographic and playful aspects demystify the violence that these objects represent. They are typical of a mutability that blurs boundaries. Childhood viciousness and surviving things come to mind through the imagery of innocence the pieces carry with them.

Overall, the artworks are reunited within a fictitious universe that plays with reality. Resistant is a box that ambiguously claims to be a musical instrument while telling us stories through its mask above. “It is the virtuosity of the magician delighting the spectators with portentous tricks, extracted from their boxes and magical bags.” Wizardry declares the existence of another world, using the invisible within the reign of the visible. The greasy pole, the totems of life, and Rabelais are still possible. Vous faites face à l’Idiot!

Bibliography

G. Didi-Huberman, Storia dell’arte e anacronismo delle immagini, (trad. Stefano Chiodi), Bollati Boringhieri, Torino, 2007.

P. Pascali, in C.Lonzi, Autoritratto, Bari, 1969.

May 26, 2020