Jaanus Samma, the many gay histories of Modern Eastern Europe

Emerging artist Jaanus Samma deals with stories of homosexuality in his home country of Estonia, both under the Communist regime and after its collapse.

Growing up gay in post-soviet Eastern Europe was never supposed to be easy. Even if a lot has changed since the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the instability of politics in the region, struggling for identity outside of the post-soviet context, still makes it difficult to develop an open homosexual identity. Perhaps that is why many post-Soviet artists have chosen an archival work to understand the era they’re coming from, trying to put it into the context of their present.

[Here is the artist’s website and here is the information about him on the page of Temnikova & Kasela Gallery. Ed.]

Such is the context of work by Jaanus Samma, a 37-year old Estonian artist, whose intricate work is an archival and spatial analysis of masculinity and particularly gay masculinity in the Soviet Estonia and beyond. Homosexuality was decriminalised by Lenin after the October Revolution, but since the late 1920s it was increasingly labelled by the medical and political discourse as a mental disease or as a remnant of bourgeois society and finally it re-criminalised again by Soviet government under Stalin in 1934.

Jaanus Samma, 3.50 from the series “A Chairman’s Tale,” 2015. Courtesy the artist and Temnikova & Kasela Gallery.

Jaanus Samma, Public Toilet from the series “A Chairman’s Tale,” 2015. Courtesy the artist and Temnikova & Kasela Gallery.

Jaanus Samma, Trial #1 from the series “A Chairman’s Tale,” 2015. Courtesy the artist and Temnikova & Kasela Gallery.

In his work for the Estonian Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2016 Not Suitable For Work. A Chairman’s Tale, Samma tackled the complex Estonian gay history based on his research into the Soviet archives. The title’s Chairman was a real-life kolkhoz chairman, who was expelled from the Communist party in the 1960s after being implicated in a court case dealing with illegal gay activity. He was later sentenced to two years of hard labor but not without the humiliation of the investigation and trial. After losing everything in result, the ex-chairman moved towns and worked menial jobs, but apparently getting known in the local gay communities for his scandalous behaviour and brawls. Given that the chairman was killed (allegedly by a soldier-male prostitute in something like a Fassbinder’s film scenario) in 1990 just before the USSR collapsed and homosexuality was decriminalised, his story reeks of trauma, melancholia and sadness. It comes across as a great parable of the gay movement in Estonia.

The pavilion was arranged as an opera using various media, including a film where the chairman’s last moments were staged. This project is where Samma’s interest in toilet as site of gay desire emerges. The museum aspect of the exhibition is especially interesting: it is made of objects, varying from personal items (gloves, a hat, vaseline used most definitely as a lubricant) to documents (a red party booklet) to medical instruments – or rather of torture, given his prison history. The redacted documents from the interrogation, trial papers, and finally the police photo of the chairman himself with his eyes obliterated, constitute a powerful and contradictory story of both Soviet ideology and the individuals it has crushed, strongly implying that the chairman’s position wouldn’t improve greatly in the “democratic” future. As for the development of the gay rights in Estonia, Jaanus Samma maintains it is getting better:

LGBT topics are still a taboo, but I feel they are much less so than even in the early 2000s. Young people who are growing up now have parents who were born in a time when it was possible to travel and see the world. The parents of my generation were born in the 1950s–1960s and obviously the understandings of that time were very different.

Another layer of the chairman’s story was provided by the Vabamu Museum of Occupations and Freedom in Tallinn. Opened in 2003, it hosted the exhibition in 2016. While Samma’s work is not a clear implication of the regime, the Museum hosting it has no such qualms, specialising in “Secret Services interrogation chambers.” Since the 1990s many such institutions have opened across the former Soviet Bloc. A specific kind of process began: not only “desovietisation,” but the creation of a whole institutional infrastructure to commemorate anticommunist resistance and condemning the socialist past. By locating homophobia not only in the realms of the soviet past, Jaanus Saama’s work was a brave foray into the institutionalised anti-communism.

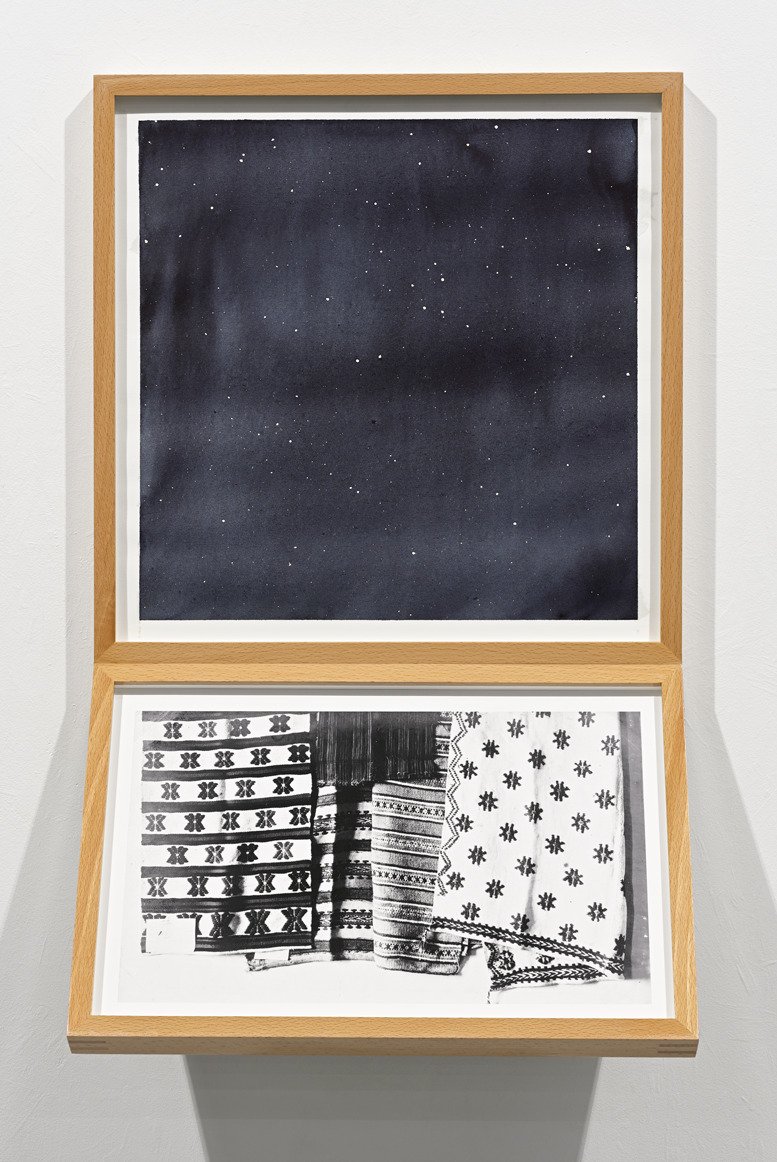

Jaanus Samma, Museum Display (Stargazing). Belts, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Temnikova & Kasela Gallery.

Jaanus Samma, Museum Display (Stargazing). Rugs, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Temnikova & Kasela Gallery.

Jaanus Samma, Museum Display (Stargazing). Dairy Utensils, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Temnikova & Kasela Gallery.

The artist is clearly interested in Museums and history, delving into the topics with his two other major works: Museum Display and the Mythology of the Toilet. In the former he focuses on the connection between manliness and folk culture, namely costumes.

Museum Display was my attempt to think of heritage and museums in general. How objects are used to create narratives and explain history. Politics, morals, ideology, trends–all of these things have a part to play in the narratives presented by the museums.

In Museum Display he puts together objects from folk textile culture of the Soviet past and gives a queer twist to them.

I always feel a guilty pleasure when I can queer folk culture, because folk culture is usually presented in a such a sweet, national, and romantic way, loaded with nationalistic ideology.

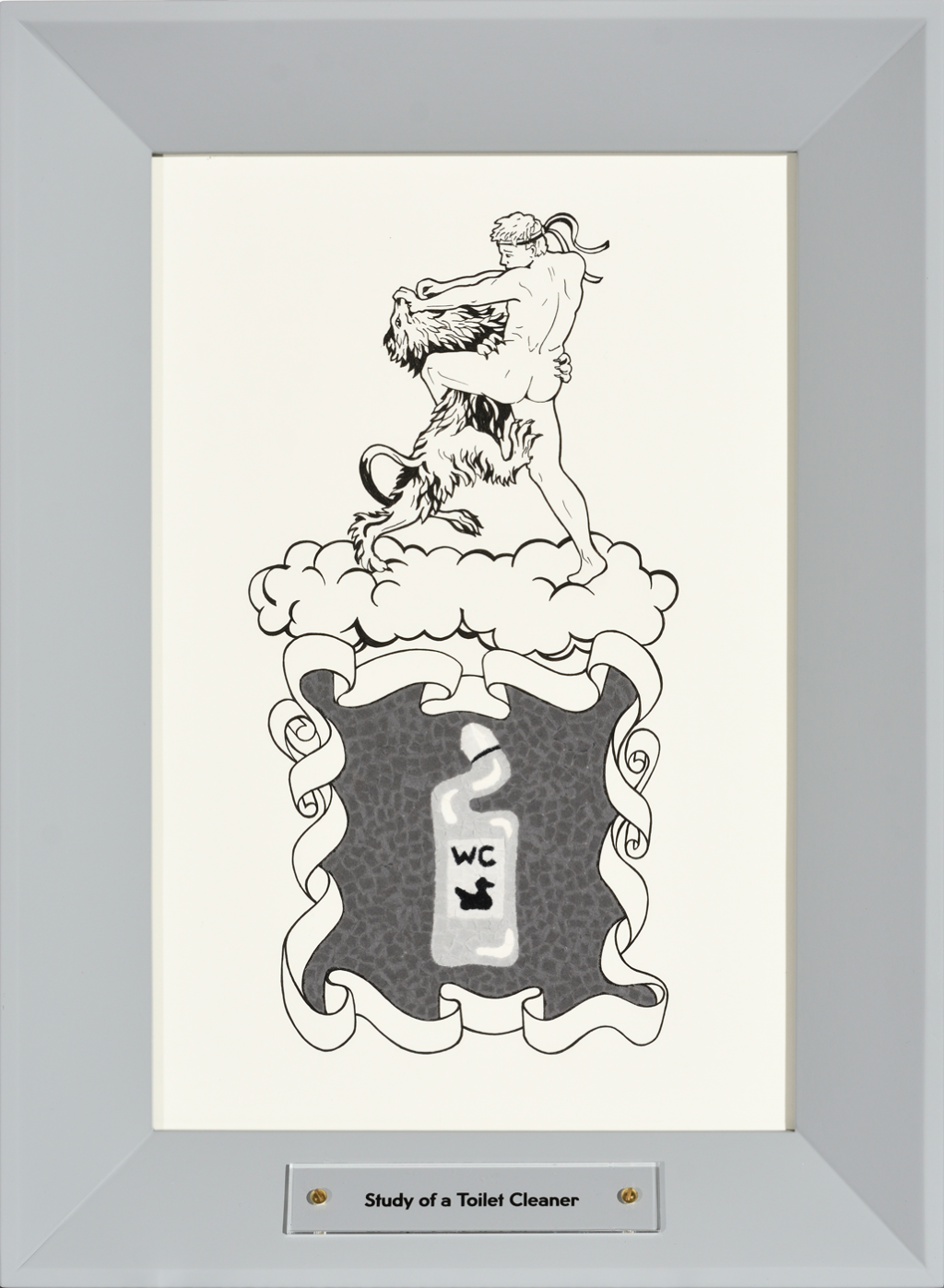

Jaanus Samma, Study of a Toilet Cleaner, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Temnikova & Kasela Gallery.

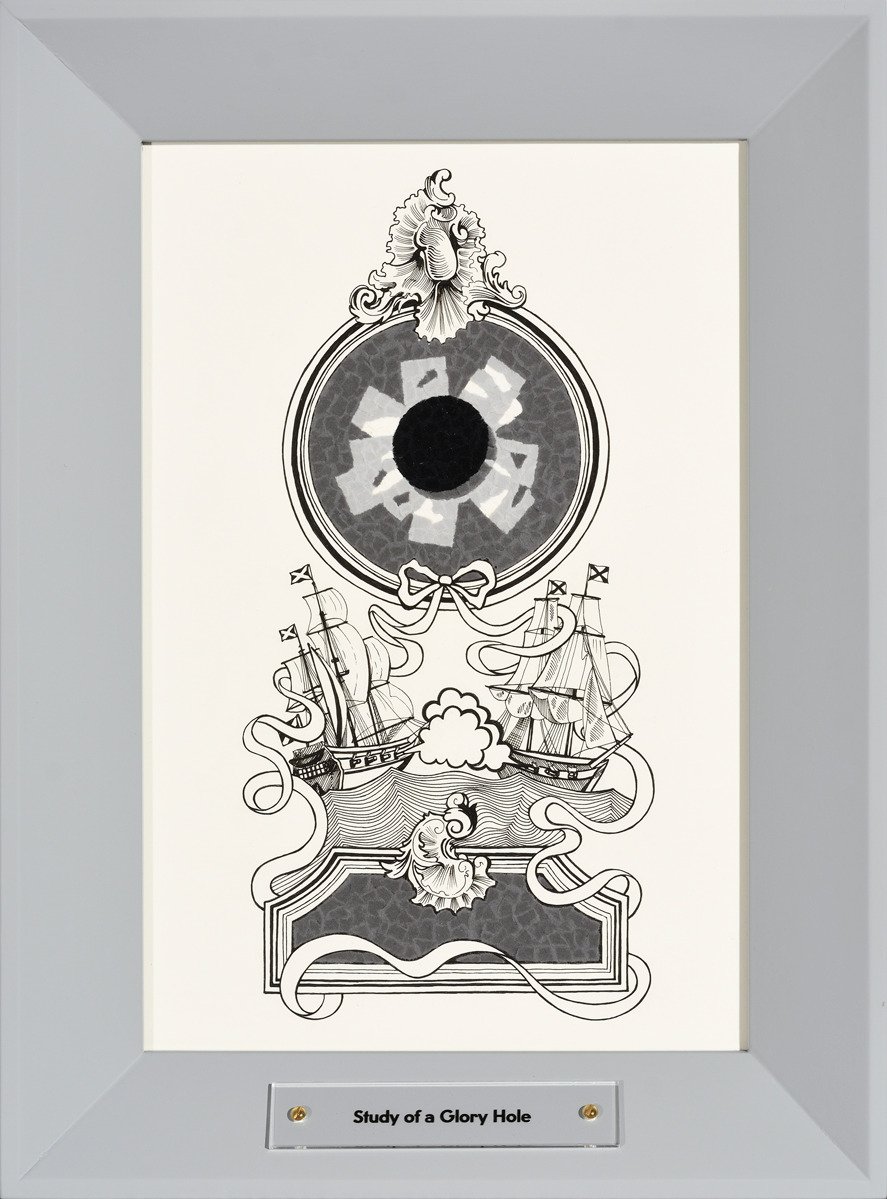

Jaanus Samma, Study of a Glory Hole, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Temnikova & Kasela Gallery.

His loving ambivalence towards folk culture provides a new outlook of its various ideological uses. While researching gay and cruising culture, Jaanus Samma begun working on toilets, as they are a perfect example of “occasional architecture,” being a public and private space at once, while remaining the unofficial architecture of gay desire.

My interest in toilets began when I researched gay history in Estonia and understood the significance they used to carry as meeting places. I was especially intrigued by the fact that these public restrooms were often located in the heart of the city, e.g. in central squares, central train stations. It is funny to think that at a time when sexual intercourse between two men was illegal it took place right in the middle of everything.

Toilets also interest him as a “non-place” as defined by the anthropologist Marc Auge.

It is often hard to find old photographs of public toilets even when they were located on central squares. It is as if we don’t see these buildings. I find it very telling how we close our eyes on something that is ugly or disturbing.

Jaanus Samma is not the only post-Soviet gay artist interested in looking into the gay past to piece the present together. Russian-American Evgeny Fiks created his project Moscow, where he traced public places, mostly toilets, of cruising during the Soviet era and put together dictionary of gay Yiddish parlance. Polish Karol Radziszewski created the Queer Archives Institute, where he collects all kinds of expression of the LGBT movement in Eastern Europe and is involved in recreating Polish gay cultural past. Samma looks into darker aspects, such as the penitentiary aspects of gay lives, but there’s hope in his works that such history shall never happen again.

October 14, 2021