Why take an artwork from the place it was made for?

Bringing works of art out of museums and back to their places of origin is what we should do: the future may begin in the church of Santa Corona in Vicenza.

It is no coincidence that the church of Santa Corona in Vicenza had struck Roberto Longhi to the point of inspiring one of his most famous essays on Venetian painting. The quantity of masterpieces in the building compares to major international museums. Walking through its naves today, the words spoken a few days ago by the director of the Uffizi Eike Schmidt come to mind: “State museums should return some paintings to churches, following the principle of cultural heritage as a widespread museum.” [Here is the statement. (Italian). Ed.] Schmidt’s proposal has started a debate on a new way of understanding the enhancement of artistic heritage. His idea seems excellent to us but many don’t share the enthusiasm.

[Here is our analysis about the lack of digital literacy of Italian museums, including the Uffizi. Ed.]

Bringing the works of ancient Italian art back to their original contexts would have more than one virtuous consequence. It would entail “demusealisation” and the consequent “defetishization” of the masterpieces; it would allow the recovery of historical, architectural, cultural and religious connections; it would ensure the spread of the artistic heritage and the enhancement of new territories. Instead, Eike Schmidt’s vision hasn’t really found receptive ears. Except a few enthusiastic supporters, most museum directors said they are against it, and perched behind the issue of safety for the works. Yet Italy is full of churches where the works still live in their original context. And the church of Santa Corona in Vicenza is a splendid example.

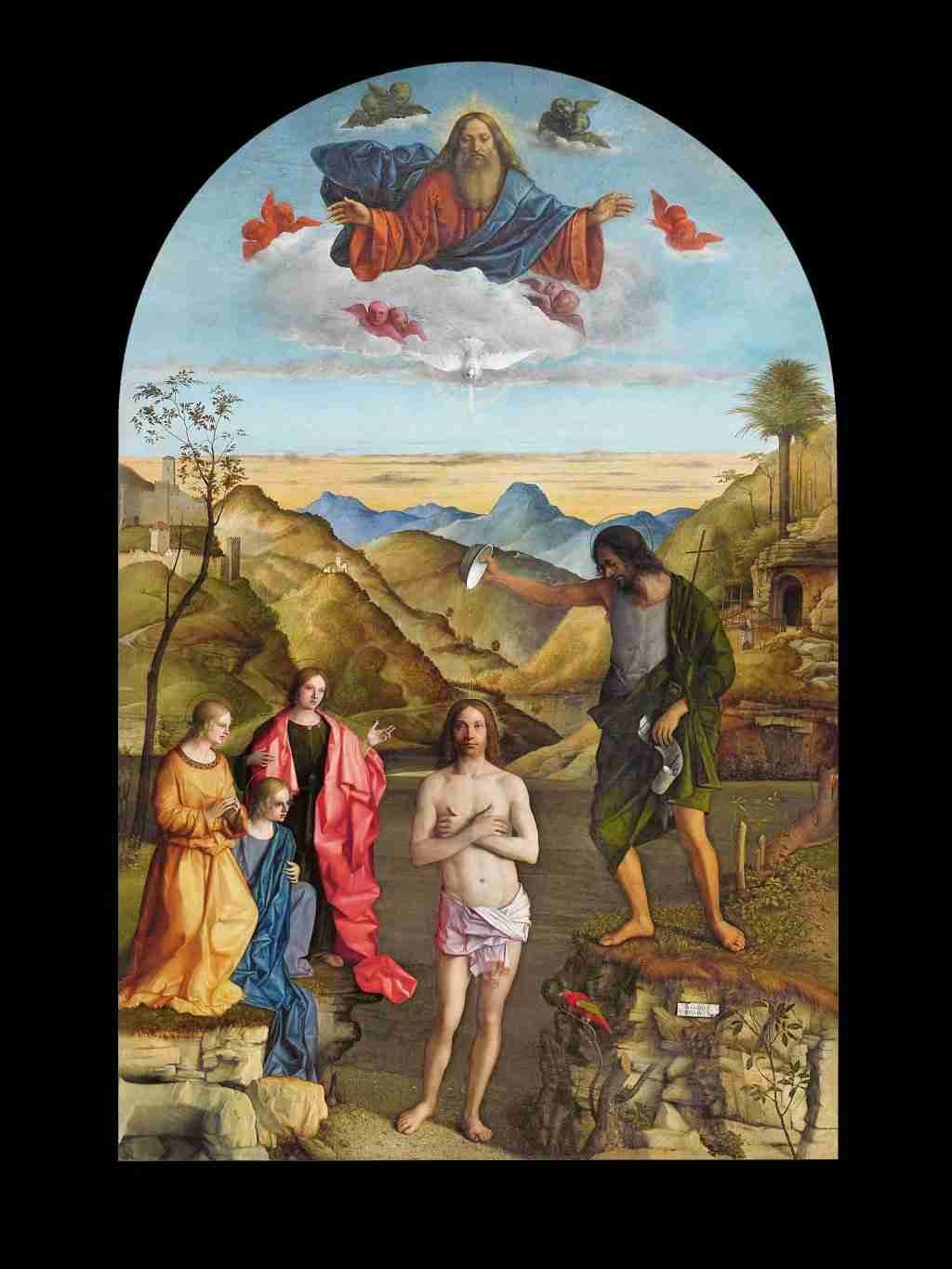

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona, “Baptism of Christ”, by Giovanni Bellini, 1500-1502, tempera on panel – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona, “Adoration of the Magi”, by Paolo Caliari known as Veronese, 1573, oil on canvas – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona, “Santa Maria Maddalena with the saints”, by Bartolomeo Montagna, 1514 – 1515, tempera on panel – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona, “Madonna of the stars”, by Lorenzo Veneziano and Marcello Fogolino, sec. XIV, oil on canvas – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

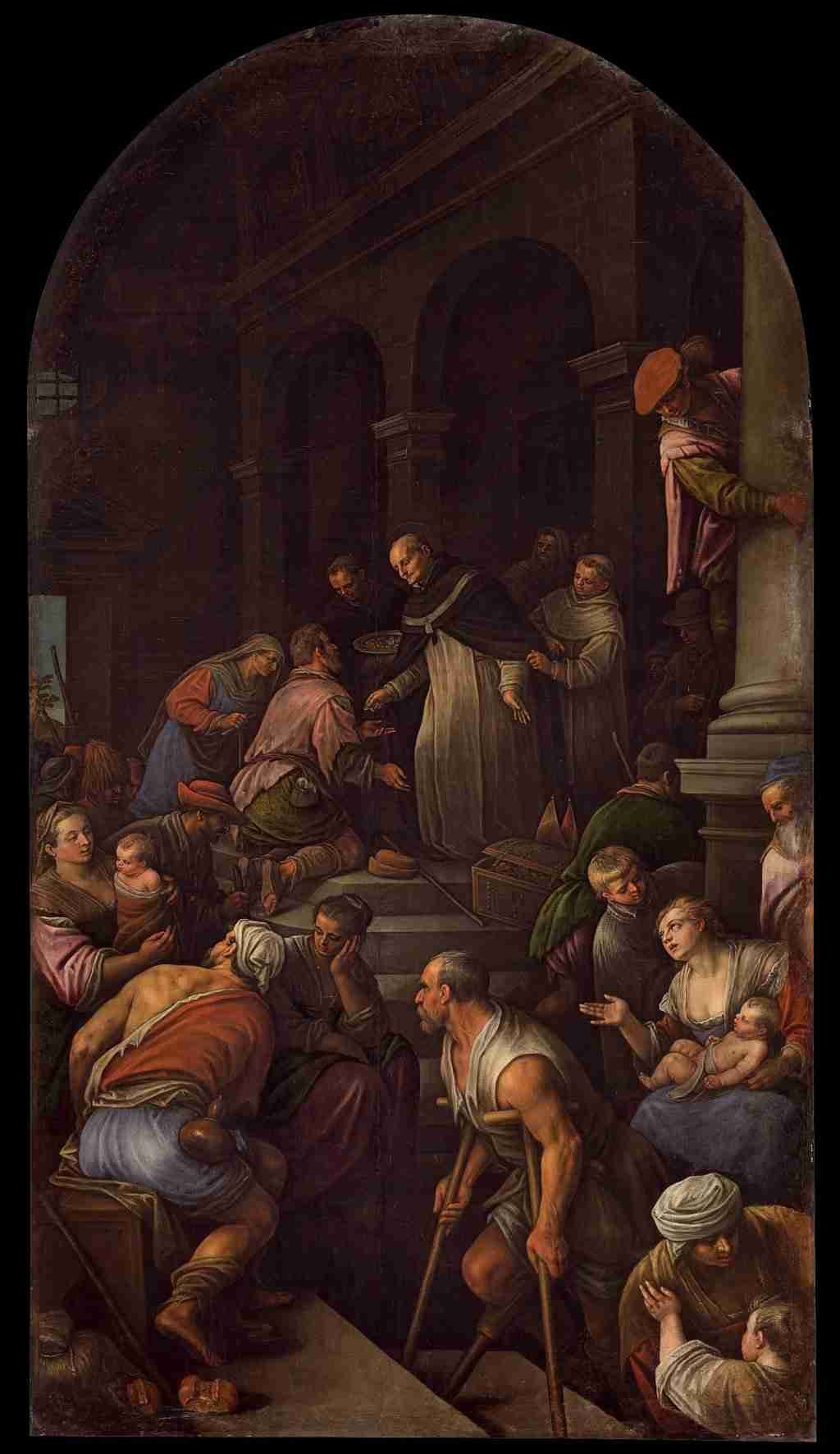

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona, “Charity of Sant’Antonio” by Leandro Bassano, VVI sec., copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona, “Madonna with child”, by Giovanni Battista Pittoni, 1723, oil on canvas – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Built in 1260, this Dominican church played a very important cultural role for the city for at least five centuries. Already in the 14th century it boasted a public school of philosophy and a very precious book collection. Being one of the symbolic buildings of Vicenza, it had quickly become a space coveted by the wealthiest families in the city. Many of them wanted to link their names to those of the altars in the church. From the Renaissance until at least the 18th century, they commissioned and donated important works. Among these, an absolute masterpiece by Giovanni Bellini: the Baptism of Christ.

Placed on the Garzadori altar for which it was made, The Baptism of Christ is a mature work of the painter, dated around 1502 and signed on the rock below “IOANNES / BELLINVS.” It is precisely this work that Roberto Longhi had in mind when he described Bellini as “one of the great poets of Italy.”

Man of tireless meditations, never satisfied to evoke the ancient, to understand the new and to experiment with them both, he was all that is said about him: first Byzantine and Gothic, then Mantuan and Paduan, then following Piero and Antonello, and lastly Giorgionesco: yet always himself, warm-blooded, heartfelt breath, in full and deep agreement with history and the cloak of nature.

In his pompous prose, which today can make us smile with its poetic pretence, Roberto Longhi exactly identifies the most relevant aspect of Bellini’s work: the perfect synthesis between the human dimension of the characters and the sanctity of the subject, enhanced by the wonderful nature around them. A little further on, focusing on the most significant parts of the painting (the sky and the mountains), Longhi writes:

In the calculated closure of the horizon, within the circle of the highest mountains, the color acquires the density of a breath that comes from the underground (perhaps, as Cézanne said, ‘from the center of the earth’). The old mountain hum seems to sum up slowly from the gulf of heaven, blindfolded by motionless clouds, as if to show more solemnly the sublime action of that valley, unobtainable but for our gaze, since Bellini discovered it to us.

A few pages further on, Longhi reminds us that no client would ask a Renaissance painter to depict a mere landscape, and that therefore the artist had to work on it within the requested subject. The search for a new language, even in the 15th and 16th centuries, was not unlike that which would later animate authors such as Monet and the Impressionists. Beyond its devotional value and complex iconography filled with theological symbols, Bellini’s Baptism of Christ is in fact a formidable example of landscape painting.

It is greatly important that we are today able to experience the quality of this work in the place to which it was intended since its commission, that is, in the context of academic research and religious devotion that this church still preserves.

With its Cistercian plan and the subsequent architectural changes that stratified over the centuries, the church of Santa Corona still has the flavor of a living organism, in which the different artistic disciplines intertwine between styles and languages. The relationship between the marble altars and the paintings still represents the necessary link between painting and architecture.

Above the Garzadori altar one can find one of the earliest classicist sculptures in Vicenza. The altar is attributed to Rocco da Vicenza (c. 1495-1530), heir of the workshop of Tommaso da Lugano and Bernardino da Como: the “factory” in which all the most important sculptors from Vicenza had their apprenticeship or workshop. What would happen to the marbles of the Garzadori altar, the perfect counterpoint to the painting, if Bellini’s work was moved to a museum gallery? They would stay silent, stripped of their links between shapes, figures, and spaces in the picture.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

Vicenza, Church of Santa Corona – copyright and courtesy Musei Civici di Vicenza – Chiesa di Santa Corona.

The church of Santa Corona can be visited as if it were a permanent exhibition, a parade of the best of what Venetian culture produced over five centuries. For example, in the chapel of San Giuseppe (the third on the right) one can find the Adoration of the Magi, a work of Veronese’s maturity, destined to powerfully influence the development of painting in Vicenza.

In the chapel of the Rosary (the fourth on the right), one can enjoy paintings by the Vicenza mannerist Alessandro Maganza along with sculptures from the Albanese’s workshop. The Thiene chapel (at the end of the nave) shows a compelling stratification of artworks: the Madonna and Child by Giovanni Battista Pittoni, active between the 17th and 18th centuries, sits next to 14th century sculptural decoration modified in the 19th century, flanked by very rare fresco residues by Michelino da Besozzo.

The Turchini altar hosts the Madonna delle Stelle by Lorenzo Veneziano, a refined painter who lived in the region of Venice between 1356 and 1372, whose works are also kept in museums such as that of the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, the Correr Museum in Venice, the Birmingham Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. The Monza altar (in the third bay on the left) houses the Charity of Sant’Antonio by Leandro Bassano, mounted in a classicist sculptural frame. The Porto Pagello altar (in the second bay on the left) one can find Santa Maria Maddalena tra Santi by Bartolomeo Montagna.

These are just some examples of the many testimonies contained in the church of Santa Corona. Big names and lesser-known authors (some of which are still at the center of attributive debates) unfold in this building, which still shows the mix of culture where painting, sculpture, architecture, history and devotion are intertwined. In short, the church of Santa Corona offers a practically inexhaustible experience of discovery, which museums are unlikely to offer today.

Back to Schmidt’s proposal, if the example of the church of Santa Corona was not enough, a further one might show that bringing ancient Italian artworks back to their places of origin is a good idea. It comes from the Uffizi Museums, albeit from the pre-Schmidt era. In 2008, under the direction of Antonio Natali, a project called Città degli Uffizi put forward the idea of exhibiting works from the museum’s storage by bringing them back to their places of origin.

In 2009, for example, a triptych by Agnolo Gaddi, an interpreter of Giotto, left the Uffizi warehouses to become the protagonist in an oratory lost in the wheat fields between Florence and Bagno a Ripoli. The triptych was brought to the altar for which it was designed six hundred years earlier. It was exhibited along with panels made by the same architects as the 14th century frescoes that adorn the church. Ancillary activities had also been organized to cover most of the costs of the exhibition. With eight iterations during three years, La Città degli Uffizi brought to the fore great masters such as Beato Angelico, Masaccio, Benozzo Gozzoli, but also little-known but remarkable artists strongly linked to the territory.

So why not turn those successful but temporary experiments into permanent situations today? Why not give new life to the many potentially rich churches such as those of Santa Corona, which are scattered all around Italy? The model is plausible, and security issues just seem to be the pretext not to back up such vision, whose feasibility has been demonstrated by the experience of La Città degli Uffizi.

The current conservation systems made available by contemporary technology could dispel any fear for the physical integrity of paintings and sculptures. We need to start again the debate about bringing Italian ancient artworks back to their original context. The move would provide an entirely new look on heritage, and perhaps a new history of Italian art could also be rewritten.

Bibliography

- R. Longhi, Viatico per cinque secoli di pittura veneziana, in Longhi, Da Cimabue a Morandi, Meridiani Mondadori, Milano 2011

- G. Zorzi, Contributo alla storia dell’arte vicentina nel sec. XV e XVI, Venezia 1925

- G. Mantese, Memorie storiche della Chiesa vicentina, Neri Pozza, 2002

- M. E. Avagnina, G. F. Villa, Bellini a Vicenza. Il Battesimo di Cristo in Santa Corona, Biblos, 2007

November 25, 2020