What are combs for besides untying knots?

The answer to combs collecting lies in the artists’ creativity, from the Etruscans, to Füssli, Man Ray, Picasso, Dalí, Calder…

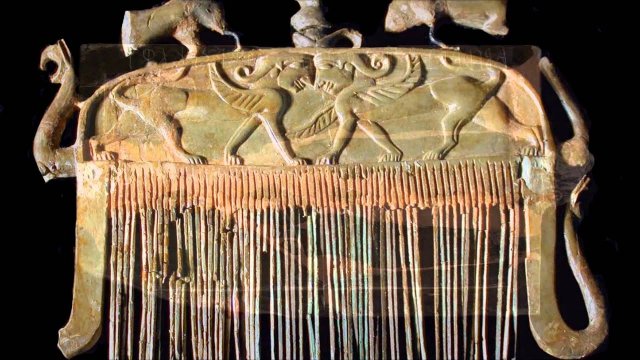

Combing one’s hair is an ancient and evocative gesture. Combs from 4000 BC were found in the Upper Egyptian cemeteries of Naqada. The Etruscans buried their dead along with make-up kits, including pins, brushes, nail polish and combs, which were decorated with scenes from myths or everyday life. They believed that a person should be perfectly groomed before meeting the gods in the afterlife.

Ancient Roman epigraphs mention the art of proper combing, a skill of the ancient coiffeurs: the pectinator and the ornatrix. In his Ars Amatoria (the art of love), Ovid gives an account of hairstyling: “Every woman chooses her favorite hairstyle in front of a mirror. Some prefer to ornate their hair with rings, some like it tightened to the temples, some style it finely with a thousand combs, some let it loose as it was a big wave.”

Ornamental hair brooches and hairpins were common in Pompeii. They were used to comb monumental hairstyles, true precursors of the massive wigs popular during the time of Louis XIV and his successors in France. In his Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga defines those wigs as “the most Baroque thing in the whole Baroque.”

Hidden in jeans pockets like they were small handguns, combs shaped the banana-looking tufts of Elvis or his emulator Fonzie; the hidden “weapon” was popular with wigged men at the French court too. They would use the comb to tame misplaced curls and keep the “mountain” of hair in shape. Made of precious ivory, tortoiseshell, or less expensive bone or boxwood, combs became an important accessory of the fashionable man at the time. They also became a decorative accessory in their own right, to be kept in the hair as ornaments. Comb designers of the second half of the XVIII century made versions with longer teeth to ensure a firm grip.

Napoleon’s first wife Joséphine de Beauharnais gave the name to a brand of hair ornaments, which included parures of needles, tiaras, decorative combs with cameos engraved in nacres by French jewelers Nitot, Mellerio dits Meller and Pitaux, depicting classic and Renaissance views of imperial Rome. Particularly valuable were those made of “micromosaic,” a technique mastered by Giacomo Raffaelli, an artisan working at the Vatican Mosaic Studio and founder of a mosaic school in Milan. His neoclassical figures were made of enamel mosaic pieces less than one millimeter in size. Here below are two examples from the collection of Gabriella and Giorio Antonini, a treasure of almost two thousands ornamental combs, gathered from the 1960s and later donated to the Musec in Lugano, the Swiss Museum of Cultures. In the Neoclassic and Romantic period, the glories of the haute couture hairstyling dear to the French court came to life in the trichophilie of Johann Heinrich Füssli, a painter of nightmares but also of graceful hairstyles.

At the 1862 International Exhibition, the English inventor Alexander Parkes presented the parkesine, the first artificial plastic. A few years later, the American John Wesley Hyatt invented the celluloid, a versatile, innovative and inexpensive material that replaced ivory and tortoiseshell in many of their former uses. Thanks to these innovations, combs became mass products, synthetic replicas of costly natural materials. At the same time, the Art Deco and Nouveau style distanced themselves from massification and the galloping industrialization. Artists and jewelers from the period created daringly designed combs, most famously those signed by René Lalique. His horn combs still used less precious materials than ivory and tortoiseshell, but borrowed figures of delicate design from Japanese painting, such as landscapes of trees at dusk. With his combs, Lalique greatly expressed the idea of ”floating nature” of the ukiyo-e world, turning organic shapes into Art Nouveau objects.

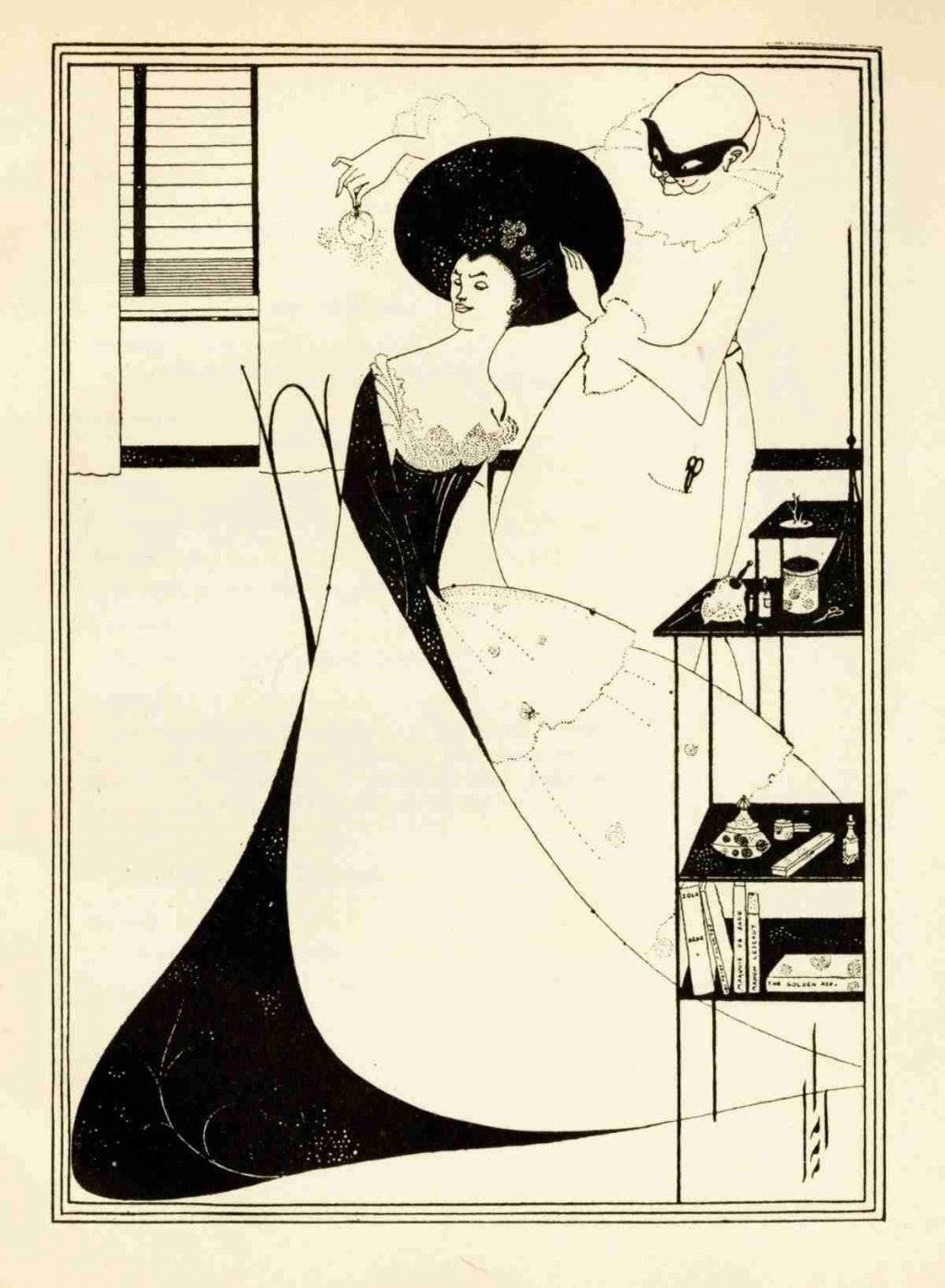

The English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley appropriated Japanese art at the end of the 20th century like no other, creating a series of ink drawings with sharp contrasts between black and white backgrounds, between refined details and pure lines. He famously illustrated Oscar Wilde’s Salomé and wrote erotic fables such as Under the Hill, a story based on the Tannhäuser. Beardsley’s short novel contains a passage about Helen’s epic hairstyle:

“Before a toilet that shone like the altar of Notre Dame des Victoires, Helen was seated in a little dressing-gown of black and heliotrope. The coiffeur Cosmé was caring for her scented chevelure, and with tiny silver tongs, warm from the caresses of the flame, made delicious intelligent curls that fell as lightly as a breath about her forehead and over her eyebrows, and clustered like tendrils round her neck.”

Kitagawa Utamaro and Utagawa Hiroshige’s bijin ōkubi-e (large-headed pictures of beautiful women) popularized the graceful beauty of Japanese women’s hairstyle and their ornaments. The Japanese coiffure owed its charme to the typical shiny black hair chignon, which could be tall or box-shaped, and to the waxed hair wings glued on the side of the face. The comb called kushi, with one or two teeth, was the only ornament allowed, sometimes combined with rattles or floral decoration to enhance the blackness of the hair.

It is a horsehair!

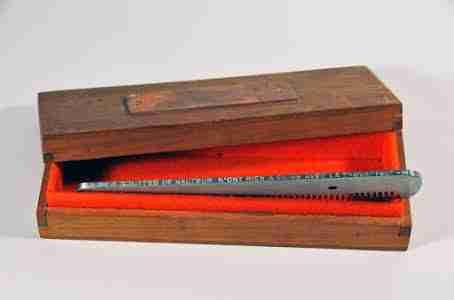

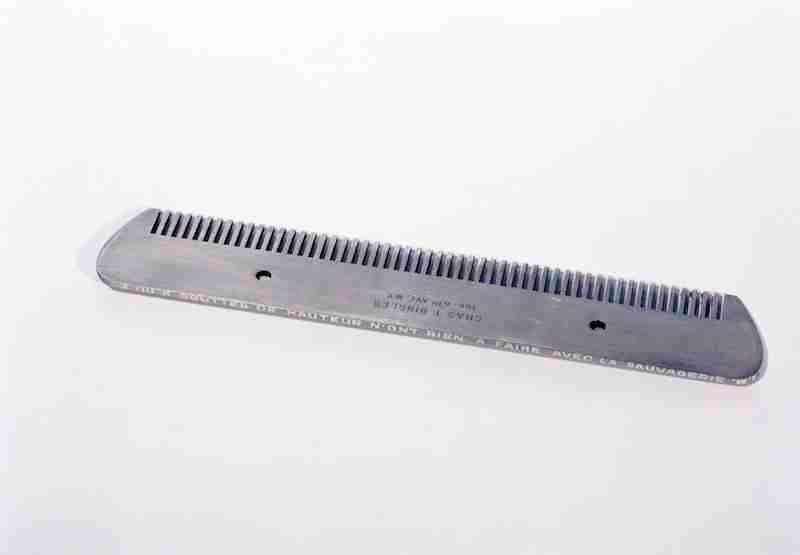

The comb is one of Duchamp’s first readymades, dated 1916 and revived in 1963 and 1964. The artist described it as follows: “A steel comb dated at the exact time of its creation and completed with an enigmatic inscription on its narrow border.” His Comb (Peigne) is perhaps a steel grooming tool for dogs or cattle. Its cryptic inscription says: “3 ou 4 gouttes de hauteur n’ont rien a faire avec la sauvagerie” (Three or four drops of height [or pride] have nothing to do with ferocity [barbarism]).

[Here is a link to the document in which Marcel Duchamp first explained the ready-made, ed.]

Duchamp coined the term “mobile” in 1931 to describe Alexander Calder’s work: three dimensional drawings made of bent and twisted thread. In the 1930s and 1940s, Calder also made a series of combs-mobiles: abstract shapes of industrial materials, often poetic and graceful, which hang in a mysteriously perfect balance. Arthur Miller’s words could be used to describe these volatile combs that seem to “float above our heads like flocks of birds, things to catch the light, to flutter with the wind.”

Marcel Duchamp, Comb (Peigne), 1916. Ready-made: gray steel comb, 1 1/4 x 6 1/2 in. Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

Marcel Duchamp, Comb (Peigne), 1916. Ready-made: gray steel comb, 1 1/4 x 6 1/2 in. Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

In Picasso’s Woman Watch from 1936, the female figure is liquefied and decomposed, reshaped and styled. Everything in the painting happens during a time that has no beginning or end. She is crouched on a pillow, sitting in front of a mirror with a comb in front of her, while forsythia branches create a headband to hold back her wavy hair.

Despite the obvious reference, the picture is not directly related to the 1515 Woman before the Mirror by Titian’s workshop, now held at the Museo de la Ceramica in Barcelona, and a variant of the more popular Woman before the Mirror at the Louvre. Everything in Titian’s picture revolves around the multiplication of mirrors: the concave at the back and the one held by the man in front create an intense play of reflections between looks and seduction, born from those voluptuously combed hair. But what does the mirror placed on the legs of the young woman painted by Picasso reflect? The black hair tied in a braid? Her breasts or sex? As Lucio Dalla sings in Disperato Erotico Stomp: “They saw you raise your skirt up to the hair: that is black!”

Picasso’s painting creates a game of adding time, not chronology, a fourth dimension of temporal malleability similar to that of Dalì’s comb-teaspoon (Montre Petite Cuillere). The melting watches in Dali’s Persistence of Memory from 1931 were painted in just two hours, inspired by the softness of the cheese the artist was eating: a true visual formula for Einstein’s theory of relativity. In his Montre Petite Cuillere, the teeth of the comb remind of clockworks: emblems, waves, fixed symbols of the persistence of memory. “An hour sitting with a pretty girl on a park bench passes like a minute” said Einstein to explain relativity to a mass audience. Not such an effective metaphor as Dalì’s melted watches…

How perfectly oval is Kazimir Malevich’s Girl with a Comb in her Hair. In his portraits from the 1930s, the creator of suprematism, forced by the Soviet bureaucrats to conform to the canons of socialist realism, speaks a language born of his love for painters of the Italian Renaissance. The result is a “SupraRenaissance,” for example in his self-portrait from 1933, inspired by the portrait of Columbus by Ghirlandaio.

[Find here our essay on Kasimir Malevich and his book “Laziness as an Actual Truth of Man”, ed.]

Yet, Malevich could never forget suprematism, and his Girl with a Comb in her Hair merges non-objectivity with figuration in a space dominated by anti-naturalist colors. The function of the comb is to cut the female figure with a line, like an arm of the cross cuts the halo of hair, creating a mix of references between sacred iconography and chromatic abstraction of pure suprematist ancestry. The pure face of the woman is close to the abstract clarity of the Madonna della Misericordia by Piero della Francesca, as well as to the Portrait of a Woman from 1564 by Lucas Cranach, who so much influenced Picasso.

In his Portrait de Jeune Fille d’après Cranach le Jeune from 1958, Picasso created a hypertrophy of pins, combs and clips pinned to the hair of the female figure. He reversed the sober formality of Malevich, presenting a baroque apotheosis of an ornament enhancing the fleeting beauty of a hairstyle. From ancient necropolises to the experiments in modern art, the ephemeral but lasting charm of the comb has never ceased to impress the artists.

November 25, 2020