A mistaken perspective on the Renaissance

Wrong, defective, crooked perspectives: they were not painters’ mistakes, but ways to represent thoughts and mysteries in the Renaissance.

The linear perspective typical of Renaissance paintings is a wonderful misconception. It is like a table that cannot stand still because its atoms move in all directions. The idea of looking at the Renaissance as “the age of perspective” falls apart as soon as we explore individual artworks in greater detail.

Not only does the linear perspective fail at identifying the Renaissance, it also falls short as a “symbolic form,” a concept expressed in a very successful book by Erwin Panofsky from 1927, which bears the same title. The work of a series of art historians, with Daniel Arasse in the lead, has challenged some aspects of the Panofskian theory, by exposing a linguistic trap in which the German historian had become entangled.

Panofsky speaks of the linear perspective as a “discovery,” not an “invention.” He believes that paintings mimic reality. Yet our way of seeing is very far from the monofocal fixity of the linear perspective, the one that Filippo Brunelleschi had first developed at the beginning of the 15th century with his experiment with boxes and mirrors in Piazza della Signoria in Florence.

Try to stare at a built environment for a prolonged time and you will notice how our eyes are unable to stay still. They try to compose a larger image thanks to continuous movements, collecting infinite details and then transmit them to the brain to create an idea of a unity. Linear perspective is the way we seem to see, not the way we see.

The workings of our vision are closer to a Cubist painting, not a Renaissance one, and surely not a photograph. The perspective was an invention rather than a discovery, a way to add further meanings to the illusion of the visible form, understanding it as a work of thought, as a political instrument, and finally as a possibly theological story of the invisible.

Writes Daniel Arasse: “Perspective is a completely arbitrary system of representation, which was invented not by a single individual but by an entire society over the course of a century (…). From the point of view of historical chronology, the success of the perspective in Florence is intimately linked to the political representation of the powerful Medici family: a pictorial form with somewhat moral principles of sobrietas and res publica.”

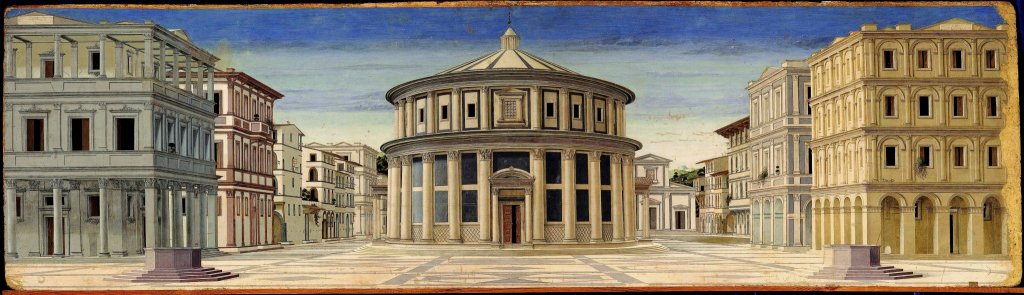

In the Florence of the Medici, decisions were made on the square, a place where freedom was appointed. The square was the symbolic center of political action, and the square itself was the real protagonist of the Florentine pictorial perspective of the 15th century, unlike the courts of Northern Italy. For some painters perspective was a useful tool to create an orderly, regular and well-proportioned world. Think of the three famous and mysterious tables of the Ideal City of Urbino, Baltimore and Berlin. For others, however, perspective went hand in hand with errors and imperfections, drawing new meanings from those diversions.

The privileged subject to experiment with linear perspective was the annunciation. Its setting between the colonnades and the hortus conclusus allowed better than anything else to focus on the three fundamental elements of the perspective: framing, vanishing point and distance point.

For example, in his Annunciazione from 1442-48, now at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, Domenico Veneziano used a perfectly geometrical perspective to frame the Virgin, except allowing himself an error: the artist painted a deliberately disproportionate door at the back. It should be the door to a city, but it is the size of a wardrobe door. The error is discovered by observing the measures of the latch, which is too small to be that of a monumental door. The door, explains Arasse, is the symbol of Christ. For this reason it does not respect the perspective. It is the figure of the incarnation, and therefore it is not literally commensurable. It does not admit a common measure between the material and divine world.

In the Renaissance, there are countless “defective” perspectives, made on purpose to render visible the invisible. Piero della Francesca was a very skilled mathematician who would have never committed gross errors in conceiving a perspective. He nevertheless painted an annunciation where a marble slab appears very close despite being at the bottom of the picture. The painting in question is the column top of the famous Polyptych of Perugia from 1460-1470, a mix technique on wood, today at the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria. According to some historians, the oversized marble would represent “the divine who was already present and invisible in the place of the annunciation,” as reported by Jacopo da Varazze in the Legenda Aurea.

There is more. Piero della Francesca also places a block of columns between the Virgin and the angel. Tracing the line between the eyes of the two protagonists, however, we discover a strange anomaly: if the angel looked up, he would not see the Virgin who is in front of him, but the columns. Thomas Parton, who was the first to notice this obstacle on the visual axis between the two characters speaks of “trompe-l’intelligence”, as if to say that the artist was simply enjoying deceiving the viewer for fun. According to Daniel Arasse, the error would instead be a precise theological message: Piero della Francesca, through the wrong perspective depicted the Incarnation with “its mystery of the marble slab found at the bottom, and its secret with the block of columns hidden in the otherwise visible thing, hidden in what is seen.”

The perspective is therefore not a window on the world, but a window to frame and tell a story. If this story foresees the presence of the invisible, the perspective adapts, becomes exceptional, and introduces an element of disorder. The history of art is made up of exceptions more than rules. “Renaissance men used perspective to build a representation of the world that would fit their actions and interests,” said Pierre Francastel.

We can list dozens of other works with anomalous perspectives. For example, Lorenzo Ghiberti would often adopt a system with two vanishing points instead of one, corresponding to each of the two eyes. Paolo Uccello also developed a bifocal perspective with two external vanishing points, following the idea that the eyes look in two different directions (right and left). His paintings St. George and the Princess and the Battle of San Romano, both housed at the National Gallery in London, are examples of this technique.

Lionello Venturi maintains that Uccello’s “perspective contradictions, rather than mathematical errors, represent a fragmentary way of seeing”. Francastel also insists on the theme of the fragments. He says of the Battle of San Romano in the London version: “the artist simultaneously employs different perspectives: elusive perspective for the foreground, compartmentalized and medieval perspective for the background. The composition is based on fragments inserted one next to the other.” Philippe Soupault even speaks of the “similarity of Paolo Uccello’s concerns to those of certain Cubist painters.”

[Here is our article on the way Paolo Uccello designed objects. Ed.]

Jean Foquet, like various artists of the 16th century, instead developed a circular or convex perspective, that is one made of shapes coming towards the viewer from the back and then leaving again. Beato Angelico even experimented with a vanishing point on the edge of the picture to create a relationship with the architecture that housed one of his works (L’Annunciazione, a tempera on wood from approx 1430, now kept at the Cortona museum). Francesco del Cossa, in his famous annunciation with a snail (the so-called Pala dell’Osservanza, a tempera on wood from about 1470, today at the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden), demonstrates that perspective ceases its fiction as soon as you look outside the frame of history. The snail in question, too big to be credible, is not part of the story. It is only part of the picture.

There was not a single linear perspective in the Renaissance. Many artists did not care at all to use it and several others purposely contravened its rules. Linear perspective eventually prevailed over other forms throughout history, up to Impressionism at least. In general, as the sociologist of art Alessandro Dal Lago says so well: “the truth of perspective in painting is at the same time the reduction of the viewer to an abstract point and the disappearance of the painting as an artifact.” Leaving aside the suggestions of Roberto Longhi on the “mysterious conjunction of mathematics and painting” in Piero della Francesca, and on the “metaphysics that arose from the new enthusiasm for spatial certainty,” those artists who instead shook those certainties for reasons of faith, narration, or simply for fun are more interesting today.

Bibliography

- André Chastel, “Vedute urbane dipinte” e teatro, in Teatro e culture della rappresentazione. Lo spettacolo in Italia nel Quattrocento, a cura di R. Guarino, Bologna, il Mulino, 1988

- André Chastel, Arte e umanesimo a Firenze al tempo di Lorenzo il Magnifico. Studi sul Rinascimento e sull’umanesimo platonico, Einaudi, Torino, 1964

- Philippe Soupault, Paolo Uccello, Editions Rieder, Paris, 1929/ Abscondita, Milano, 2009

- Lionello Venturi, Paolo Uccelli, in l’Arte, 1930

- Pierre Francastel, Lo spazio figurativo dal Rinascimento al Cubismo, Torino, Einaudi, 1957

- Daniel Arasse, Histories de peintures, Éditions Denoël , Paris, 2004/Storie di pitture, Torino, Einaudi, 2014

- Erwin Panofsky, Die Perspektive als “Symbolische Form”, Lipsia, Berlino, 1927/La prospettiva come “forma simbolica”, Abscondita, Milano, 2007

November 25, 2020