Giant Polaroid, innovation or preservation?

A brief history of the Giant Polaroid, the largest transportable Polaroid ever built, which put together the art of photography with art itself.

The invention of Polaroid photography in the previous century was a radical revolution in terms of technology, society and culture. Polaroid was a great success in the amateur market due to ease of use and surprising printing times, but in the pre-digital era many professional photographers systematically resorted to Polaroid too. The possibility for snapshot sampling and quality of both B&W and color films made Polaroid an irreplaceable product for the picture experts.

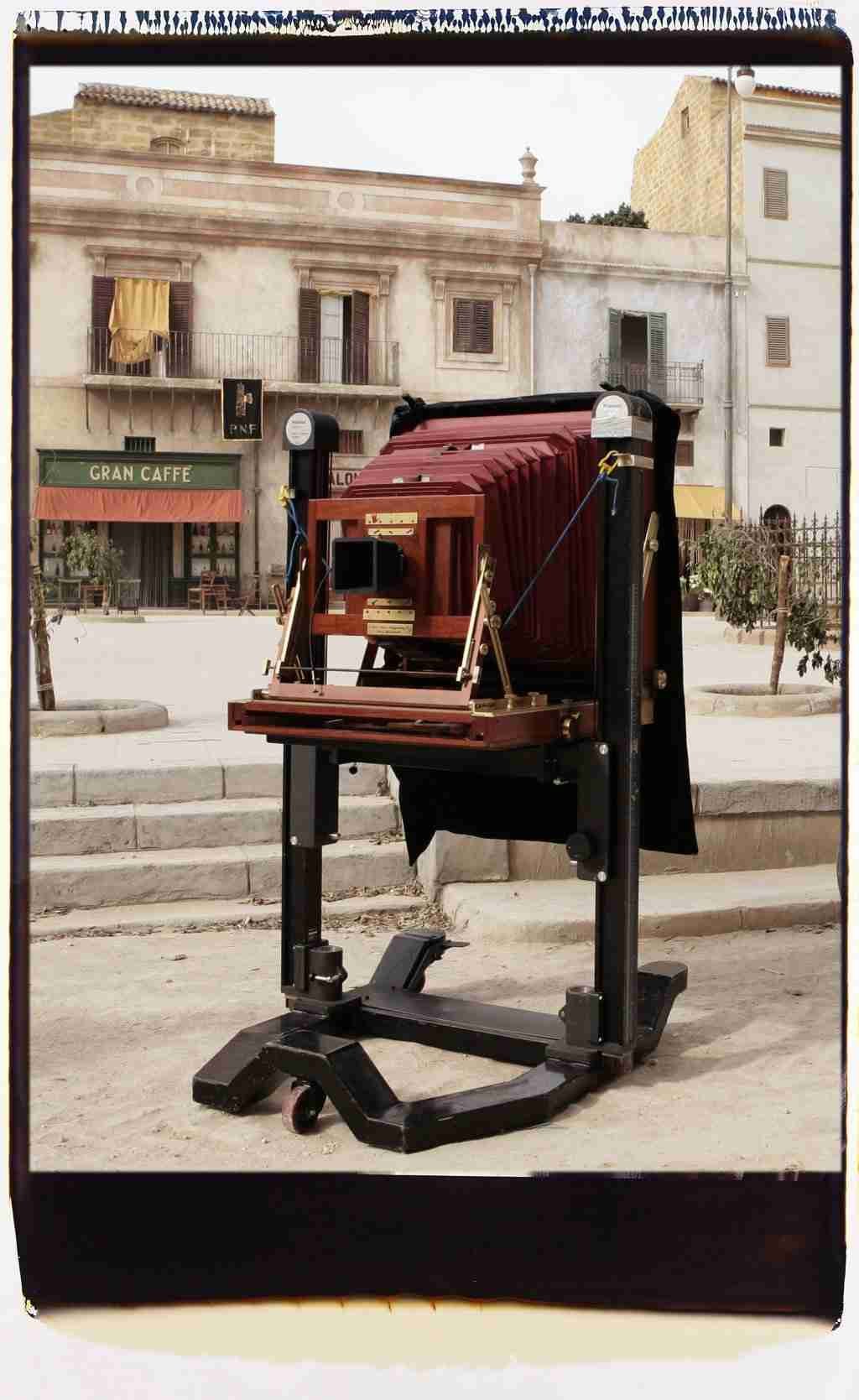

Polaroid was synonymous with speed and instantaneity regardless of the user’s profile. In the early 1970s, the invention of Polaroid 20×24 Instant Land Camera, more commonly known as Polaroid 20×24, marked the beginning of an unprecedented chapter in the history of the company. This large device capable of creating 50×60 cm pictures in a few seconds shows the complexity of Polaroid as a photographic language still today.

Giant Polaroid in fact had antithetical characteristics compared to other Polaroid cameras: heavy, hard to carry and difficult to use. It was necessary to run an extensive international marketing campaign to turn the product into a success, in particular by aiming at professional photographers and artists who, intrigued by the uniqueness of the medium, would use it for creative purposes.

Polaroid 20×24 highlights some lesser-known aspects of the company and it allows to reread its history from the perspective of media studies. It is widely believed that the advent of digital photography led to the disappearance of film, and one could think that Giant Polaroid is nothing more than an obsolete medium. In reality, the history of the Polaroid 20×24 teaches that innovation does not necessarily lead to a break with the past, [1] and that the media history is characterized by a discontinuous pace, in constant tension between innovation and preservation.

Re-reading the history of this device in the digital age contributes to the analysis of the phenomena of “remediation,” [2] a term borrowed from Bolter and Grusin which stands for the interrelationship between media, a phenomenon that is typical of our age.

From the prototype to the birth of the 20×24 studios

The history of Giant Polaroid began in 1976 when Edwin Land, founder of the company, presented the prototype of the new Polaroid 20×24 Instant Land Camera to his investors. Created with the aim of advertising the new 8x10cm Polacolor II color film, Polaroid 20×24 could print 50x60cm photographs in sixty seconds, highlighting the qualities of the new color film even from a considerable distance.

Although created to respond to commercial needs, the potential of the Giant Polaroid was immediately clear: between the spontaneity of the snapshot and the rigor of the pose photography, its charm laid equally in its dichotomous essence and surprising technical qualities. Between 1977 and 1978, five Giant Polaroids were produced and as many photographic studios were set up, available to professionals who wished to make use of this shooting format. The first 20×24 studio opened in Ames Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, at the company’s headquarters. In 1986 it was the turn of the famous 20×24 studio in New York, directed by John Reuter and still active today, followed by the 20×24 studio in San Francisco. Faced with the interest shown by the presentation of Giant Polaroid at the Photokina fair [3] in Cologne in 1978, the 20×24 studios in Amsterdam and Offenbach were set up, directed respectively by Rebekka Reuter and Jan Hnizdo. The success story of the five Giant Polaroids is therefore intimately linked to the birth of their respective photographic studios, which acted as a link between the company and a fairly large number of professional photographers and artists, attracted by the unique characteristics of the new medium.

The first Polaroid 20×24 Instant Land Camera measured 64 x 105 x 150 cm, weighed about 90 kgs and made it possible to take life-size photographs measuring 52.5 x 61 cm. The composition was made on a 50 x 60 cm frosted glass and the final print therefore had a few centimeters of lateral margin. The negative matrix and the positive support were both arranged on two independent coils mounted on special titanium rollers, arranged on the back of the device and equipped with a compartment in which the chemical reagent capsules were inserted. The result was an instant photograph of unmistakable sharpness, as it was not obtained by enlarging smaller frames. It had a characteristic irregular edge due to processing stains. [4] It was somewhat of an artisanal procedure, in which the photographer, partly constrained by the rules of the device, would take a pose photograph and “seize” [5] the image. Regular photographers would otherwise keep their eye in the camera viewfinder while moving.

The 20×24 studios at the service of artistic creation

The invention of the Polaroid 20×24 Instant Land Camera revealed Edwin Land’s desire to elevate Polaroid photography to a medium for artistic expression. With the opening of the 20×24 studios, the interest of international artists and photographers towards the 20×24 Polaroid grew exponentially. Many travelled to the studios to experiment with the new device. Not only did the invention of the Giant Polaroid strengthen the company’s presence in the United States and in the world through collaborations with public and private cultural institutions, its use by internationally renowned artists also contributed to consolidate its status as an artistic medium. Andy Warhol’s visit [6] to the 20×24 studio in Ames Street in 1979 confirms this period of fruitful collaborations.

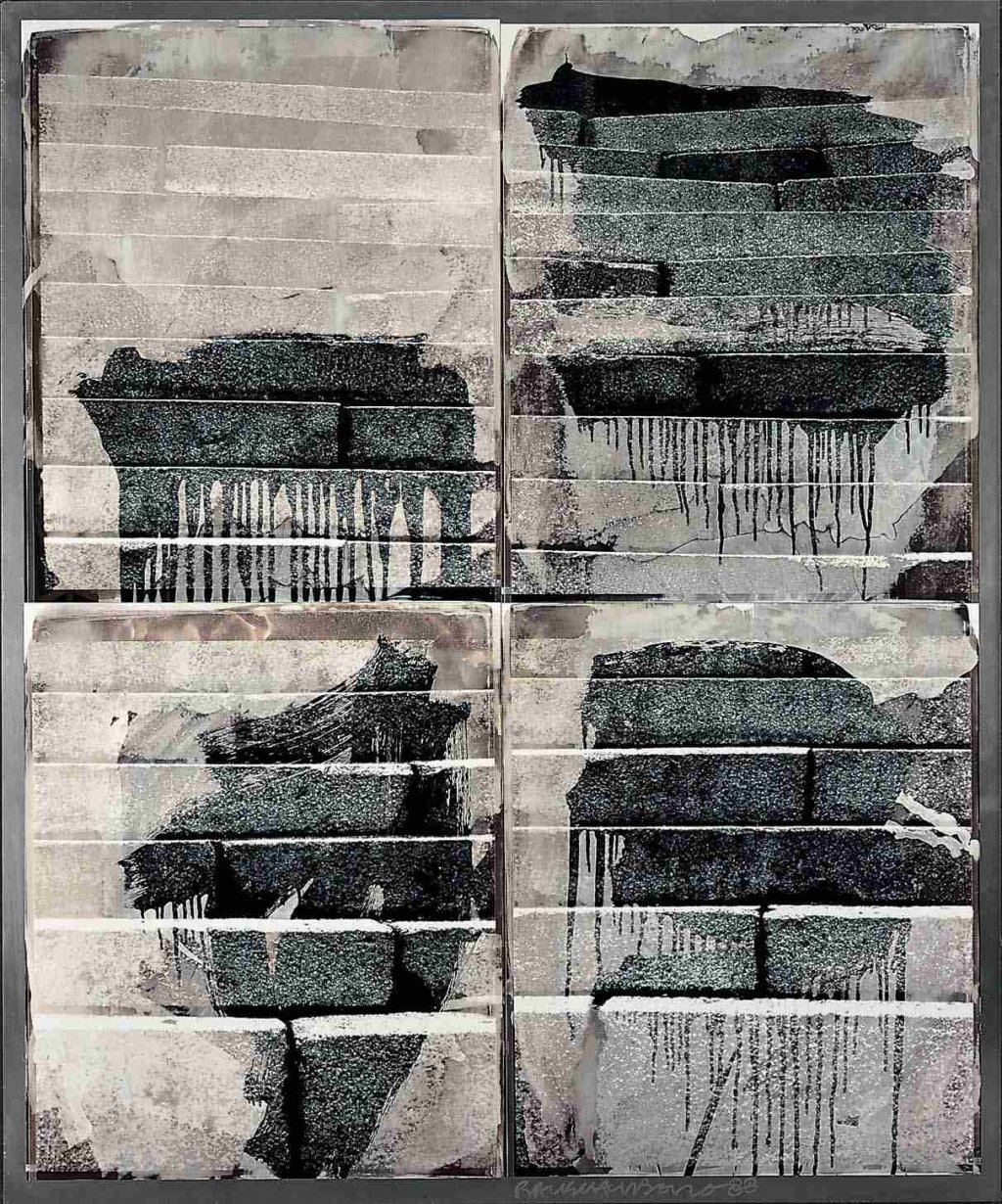

Between the seventies and eighties, the requests from artists increased to the point that Polaroid had to reorganize the operations of the 20×24 studios by intervening from the outside. The operations of exposure of the frame, lamination and separation of the positive copy from the negative matrix required a great technical competence. A close relationship between the artists and technicians of the 20×24 studios was indeed necessary. For example, John Reuter created the Miami 20×24 studio in 1987 following the desire of Robert Rauschenberg, who wanted to use the Giant Polaroid out on the streets of Miami. After an initial phase of experimentation, in 1988 Reuter also set up the Polaroid 20×24 device at the studio of Rauschenberg in New York, where the artist created large format instant photos on a special film that required an additional chemical product. By applying this chemical only in some points, the untreated parts faded, thus obtaining the characteristic effect of the well-known photographic series Bleachers, exhibited in 2013 by Pace / MacGill in New York on the occasion of the show Robert Rauschenberg and Photography. [7] The agreement between Rauschenberg and Reuter resulted in an artistic, experimental and technical use of the Giant Polaroid, a successful example of the communion between art and technology so much hoped for by Edwin Land. Bleachers marked the beginning of a new chapter in the history of Giant Polaroid, whose role in artistic creation was then definitively consolidated. At the same time, the American photographer Neal Slavin published Britons [8], an ironic and cutting-edge portrait of English society. The volume brought together the series of large-format Polaroids created during an eight-year campaign, during which the device operated in extreme weather and geographic conditions.

The 20×24 studio campaigns further intensified in the face of the growing demand from public and private institutions, which recognized great creative and media potential in the Polaroid 20×24. Among the most important institutional initiatives, the one carried out in 1985 by the then director of the Center Pompidou Alain Sayag is undoubtedly one of the most relevant. [9] Following an important refurbishing project by Gae Aulenti, Italo Rota and Piero Castiglioni, and the enlargement of the section dedicated to collections, the museum intended to promote initiatives dedicated to contemporary art. Alain Sayag invited thirteen internationally renowned artists, including Christian Boltanski and Bettina Rheims, to experiment with the Giant Polaroid in the 20×24 studio temporarily set up in the museum. The artists, who had only one machine at their disposal and operated under the same working conditions, came up with extremely different results. Atelier Polaroid was therefore an opportunity to show the technical and creative qualities of the Polaroid 20×24 to the Parisian public. Similar to this initiative at the Pompidou, the 1991 exhibition Sviluppi non premeditati [10] was organized at Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome. The title evoked a mutable show, marked by active participation of the invited artists–Mario Schifano and Nino Miglior among others– who experimented with the Giant Polaroid in the museum rooms and in the presence of the public.

Many of the initiatives involving the Polaroid 20×24, although of artistic and cultural interest, were of a commercial nature and related to Polaroid’s acquisition strategy known as the Artist Support Program. Since the opening of the first 20×24 studio in Cambridge, one of the founding principles of the project was in fact the establishment of a business collection based on the exchange with photographers, who could have used the equipment of the 20×24 studios for free in exchange for some of their best shots. Already in the 1950s, Edwin Land hired photographer Ansel Adams as an art consultant. He was the first to take care of the constitution and management of the Polaroid collection, which is now divided between two poles: the Polaroid Collection in Cambridge and the International Polaroid Collection in Amsterdam, where Luigi Ghirri made his famous large format Polaroids in 1980. [11]

Between art and technology: the Giant Polaroid for the art restorer

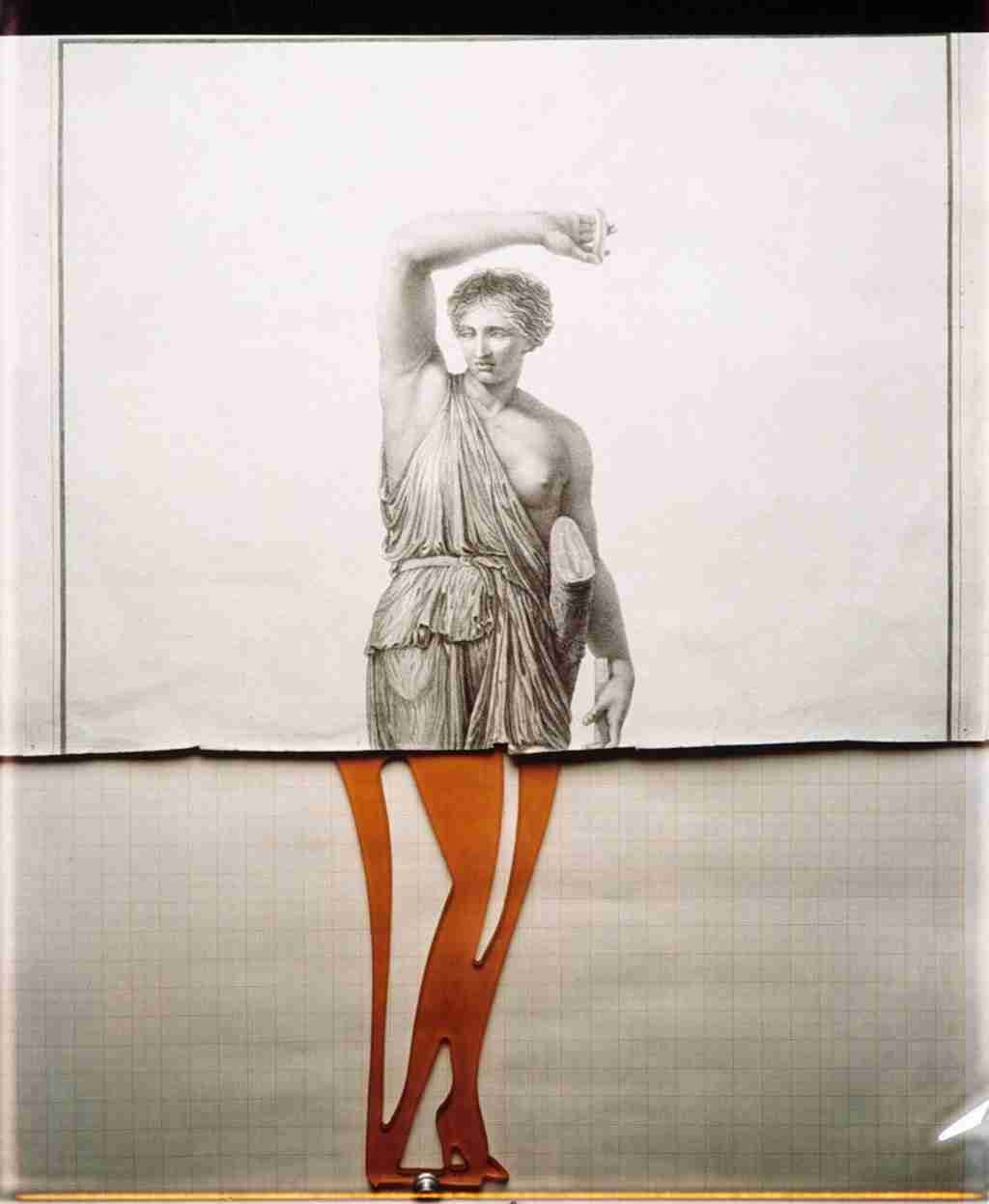

Along with collaboration with artists, the technical and commercial projects of Polaroid company help understand its socio-cultural and economic significance. The special characteristics of Polaroid 20×24 well fit in the field of scientific photography, in particular in the restoration of works of art. Giant Polaroid allowed for the creation of an instant, sharp and detailed life-size photograph. The comparison between the subject and its reproduction was possible after a few seconds thanks to immediate printing. It would help the analysis of details of monumental works, otherwise invisible to the naked eye. In the pre-digital era, these qualities were extremely valuable for art restorers.

Edwin Land grasped the potential of the medium even before the birth of the Polaroid 20×24, focusing on instant photography for scientific studies. In the 1970s he collaborated with John McCann, then director of the Vision Research department of Polaroid, in order to create a reproduction of the work Dance at Bougival by Renoir. [12] For the task, McCann built the Museum Camera, a fixed device functioning as an immense darkroom, placed in the museum room in front of the almost two-meter-high work. The Museum Camera was somewhat of a prototype of the Polaroid 20×24. Similarly, in 1979 a device was set up in front of the Transfiguration by Raphael [13] in the Vatican Museums during the restoration of the work. It could take instant photographs measuring 100×300 cm, allowing the reproduction of the monumental painting in four parts. Today, the Museum Camera for the Transfiguration has become a symbol of the fruitful combination between art and technology sponsored by Polaroid.

From museum to cinema: Giant Polaroid between art and pop culture

Giant Polaroid developed its own aesthetics and language with considerable success also thanks to the mechanical improvements by the Wisner Manufacturing Company, which marketed more modern machines in collaboration with Polaroid to meet the needs of photographers. The intense collaboration between artists, photographers and the 20×24 studios steered towards the outdoor use of Giant Polaroid. It was therefore necessary to produce more modern, lighter and more manageable devices. There are many Wisner pictures still existing today in Europe. Claudio Canova’s Milanese agency Photomovie has for decades been one of the best large-format, Wisner-Polaroid archives, which includes a still functioning Wisner camera. In 1996 the director of the Venice Film Festival Gillo Pontecorvo commissioned Photomovie and Canova with the realization of the official photographic documentation of the Festival. Canova set up a temporary 20×24 studio there, taking great care of the entire process: from the choice of photographers to the printing of the pictures in situ to the display of the best shots at the Palazzo del Cinema. In the early years alone, more than 200 giant Polaroid pictures were made per edition, a success recognized by the company itself with the gift o a Wisner camera to Canova in 1999. Thanks to the fruitful collaboration with the Venice Film Festival, Photomovie now preserves a collection of about 4000 large format Polaroids, some of which have recently been the subject of an exhibition [14] that tells the story of the protagonists of the Venice Film Festival from the perspective of a medium that influenced its aesthetic identity.

The 20×24 Studios today: nostalgia for the past and new perspectives

Between the 1990s and the early 2000s, Polaroid went through a moment of profound crisis that made the reorganization of the 20×24 studios inevitable, without however determining their definitive closure. The company was too late to realize the advent of digital photography. At the same time, interest in Giant Polaroid remained alive. On the one hand, photographers who had integrated the medium into their artistic practice didn’t want to give it up. On the other hand, digital innovation did not lead to a break with the past, but a new sensitivity in the new generations for revival and appreciation of obsolete media. From 2008 the bankruptcy of the company led to the progressive withdrawal of the films from the market, making it difficult to use the devices. In this critical moment, the role of John Reuter was fundamental. He guaranteed a future for the 20×24 studio in New York by purchasing the production license for large format films from Polaroid. Once the continuity of production was ensured, Reuter opened a new 20×24 studio in Manhattan, around which numerous prominent personalities now orbit. These include photographers Chuck Close and Mary Ellen Mark, whose production of Giant Polaroid depends strictly on collaboration with John Reuter’s 20×24 studio. Its survival was essential to the realization of her recent photographic series, undoubtedly among the most interesting artistic collaborations in the recent history of the 20×24 studio. From 2004 to 2006, it also supported various artists during the making of Prom [15], a series of portraits of American high school students immortalized during the prom. Beyond the carefree appearance of the subjects, the pictures offer a cutting edge analysis of American society.

The inauguration of the new 20×24 studio in Berlin in 2019 marks the last stage of the Large Polaroid’s long journey. Director Markus Mahla bought one of the five original devices from former colleague Jan Hnizdo [16] after the closure of the 20×24 studio in Offenbach. His studio in Berlin is now the only one, together with its New York competitor, to use one of the five original devices. The remaining three cameras are divided between museums and photographers. Until a few months ago, a Giant Polaroid was kept in Cambridge in the studio of the recently deceased photographer Elsa Dorfman. An inactive camera is now kept in Enschede in the Netherlands, previously used by the Impossible Project. [17] Another is at the Harvard Museum of Scientific Instruments. The prototype, also inactive, is now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The activity of the 20×24 Berlin studio is of predominantly commercial nature and testifies to the influence of the language of Polaroid in the popular iconographic heritage. The progressive abandonment of strictly artistic projects is not actually antithetical to the vision of Edwin Land, who sought a compromise between art, technology and popular culture. The large-format Polaroids made in 1979 by Ansel Adams to the president Jimmy Carter are perhaps one of the most successful examples of this relationship between art, commerce and pop culture with Polaroid. They began a tradition of using a 20×24 studio in the White House, giving life to a new style of presidential portrait.

Much more than a simple camera, Polaroid 20×24 has gone beyond the frontiers of art, cinema, science and communication, gathering loyal followers among both professionals and amateurs. Despite the numerous difficulties encountered following the bankruptcy of the company and the interruption of the production of the films, the attraction towards Giant Polaroid is still alive, thanks to the tenacity and passion of a relatively large number of fans, who are still faithful to the vision of Edwin Land. The strength of Polaroid lies precisely in the collective spirit: much more than a company, Polaroid is the expression of an era, of a technological, social and cultural revolution. The experience of Giant Polaroid is even more unique, as it requires an even more intimate relationship between the camera and the photographer in the studio. The obsolete nature of the device contributes to its charm and confirms the hypothesis that every technological progress does not systematically correspond to a break with the past. Photographers and artists are still willing to travel to arrange the reels, savor the moment of concentration that precedes the shot and witness the development of the image. In a world that is only apparently digitized, there is a real search for analogue experiences.

- See Parikka, Jussi, Archeologia dei media. Nuove prospettive per la storia e la teoria della comunicazione, Carocci editore, 2019.

- Bolter, Jay David, Grusin, Richard, Remediaiton. Competizione e integrazione tra media vecchi e nuovi, Guerini Studio, 2002.

- Coeln, Peter, (curated by), From Polaroid to Impossible, Masterpieces of instant photography – The Westlich Collection, Westlicht Museum of Photography, (17 Jun – 21 Aug 2011), Hatje Cantz, Vienna, 2011, p. 23.

- Rebuzzini, Maurizio, “Studio Polaroid 50×60”, in Landscape, panorama della fotografia professionale, dicembre 1986, Massimo Aldini Editore, p. 3.

- Poivert, Michel, Brève histoire de la photographie, Hazan, Paris, p. 16.

- McKeon, Nancy, “Instant Andy”, The New York Magazine, 17 Novembre 1980, n.p.

- See Craft, Catherine, Robert Rauschenberg, Phaidon, New York, 2013.

- See Ford, Colin, Waugh, Auberon, Frascella, Larry, Britons, André Deutsch, London, 1988.

- Sayag, Alain (curated by) Atelier Polaroid, Paris, Musée National d’art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, (30 May – 19 August 1985), éditions du Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1985. p. 4.

- Bonito Oliva, Achille et al., Sviluppi non premeditati. La fotografia immediata fra tecnologia e arte, cat. expo., Rome, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, (19 Sept – 11 Nov 1991), Edizioni Carte Segrete, Roma, 1991.

- Ghirri, Paola, Luigi Ghirri, Polaroïd, Baldini&Castoldi, Milano, 1998.

- Gierstberg, Frits, Pietsch, Katrin, (curated by), Ulay. What is this thing called Polaroid? Fotomuseum, Rotterdam, (23 Jan – 1 May 2016), Valiz, Amsterdam, 2016, p. 97.

- See Mancinelli, Fabrizio, A masterpiece close-up: the transfigurations of Raphael, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, Città del Vaticano, 1979.

- See Barbera, Alberto (curated by) Ritratti. Opere Uniche. 300 Giant Polaroid raccontano i protagonisti della Biennale Cinema dal 1196 al 2004, cat. expo., Venise, Hotel de Bains, T Fondaco dei Tedeschi, (26 Aug -15 Sept 2019) Venezia, La Biennale di Venezia, 2019.

- See Bell, Martin, Ellen Mark, Mary, (curated by) Prom, Los Angeles, Getty Publications, 2012.

- Gerwers, Thomas “20×24 Studio Berlin, Im Gespräch mit Markus Mahla”, Profifoto, Magazin fur Fotokultur und Technik, 2 April 2019.

- See Coeln, Peter, et. al., From Polaroid to Impossible, Masterpieces of instant photography – The Westlich Collection, Hatje Cantz, 2011.

April 12, 2021