Ancient books, an introduction

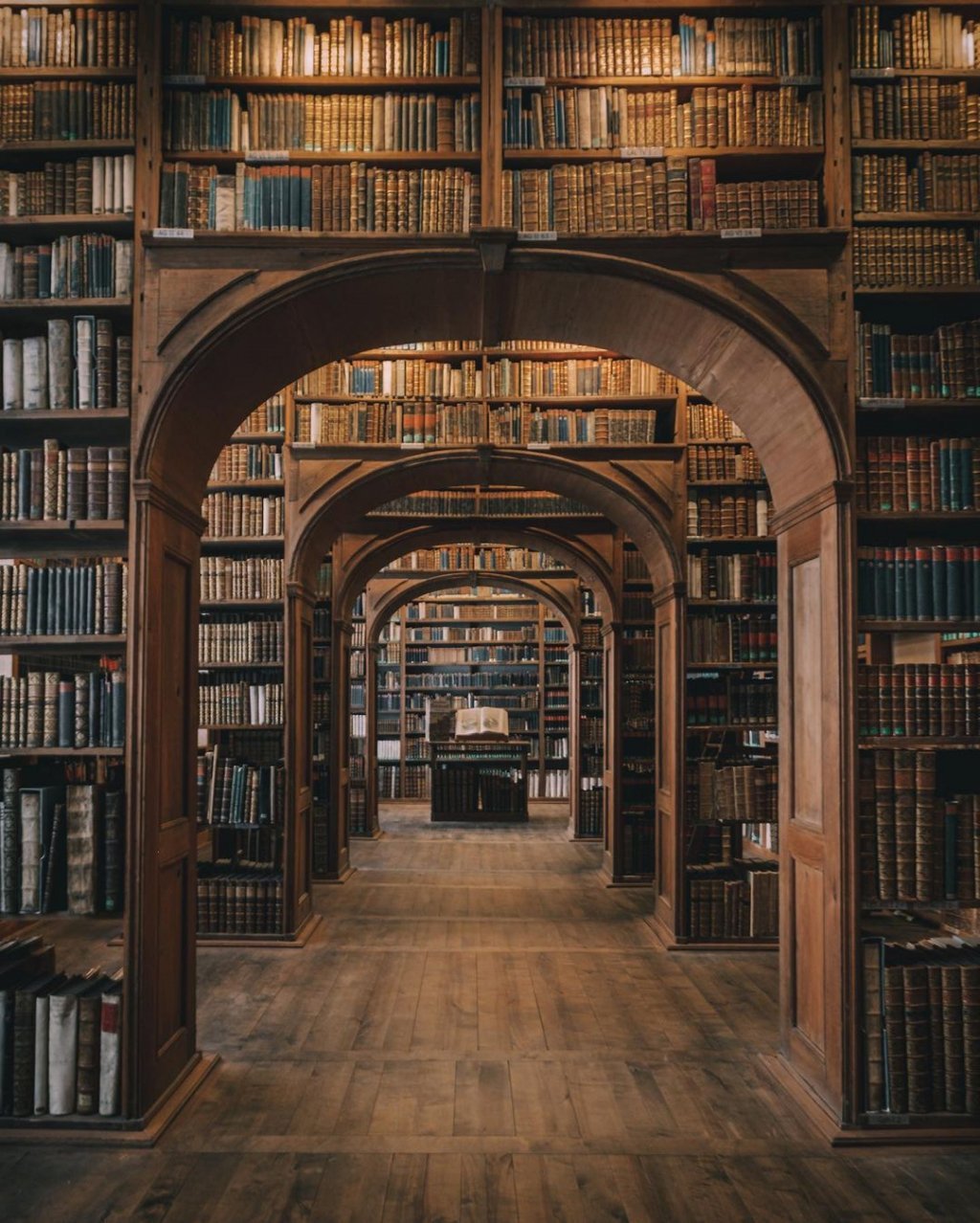

Niche within a niche, ancient books from the Renaissance are very much alive today, torn between objects of fetish and crossroads of stories.

Stephen Jay Greenblatt, one of the literary historians who founded New Historicism, writes that in the 15th century people would go as far as killing in order to steal a book. The scholar refers to an era when the hunger for books could change entire lives. In his 2012 Pulitzer Prize winner The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, Greenblatt describes the thin line between the rediscovery of an ancient book by Lucretius, Sandro Botticelli’s stylistic revolution and William Shakespeare’s poetics, showing how books played a key role in the transformations that led to contemporary society. What role do those books play today?

Ancient books are undeniably a niche. For centuries, politics and art have provided nourishment from the pages of codices and manuscripts. On the other hand, the 20th century and its vocation for revolutions disrupted the old relationship between culture and bibliophilia. The world of ancient books is now burdened with die-hard prejudices. Their preconceived image of dustiness, coupled with lack of transparency in their market, scares people off. Yet ancient books can still affect our present. The relationships between the texts of bygone centuries and the present expressions of creativity are still vivid. In a way, an ancient book can be considered as a hypertext, that is a collection of cultural references with dynamics that are similar to today’s web pages. Many examples of incunabula and 16th century volumes closely relate to 20th century and contemporary design. The boundaries of this universe expand into the visual expressions of our time.

From a commercial point of view, the market for antiquarian books seems healthy. All the main auction houses have sections dedicated to books and manuscripts. A few Italian ones are specialized in the field: Bolaffi, Pandolfini, Gonnelli, and Il Ponte. The latter opened a dedicated section in 2017. Eugenio Donadoni, a specialist in manuscripts from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance at Christie’s London, told us: “Since 2008, which began in an era of economic uncertainty, particular emphasis has been placed on the ‘classics’ that stand the test of time such as the works of Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, Adam Smith, William Shakespeare, and new price records continue to be set. For example, a complete copy of Shakespeare’s ‘First Folio’ was sold by Christie’s New York in October for about $ 10 million. The last complete copy was also sold by Christie’s in 2001 for 6.1 million dollars.”

Continues Donadoni: “The medieval manuscript market is returning to the levels of the early 2000s. Over the last few years, there has been an increase in demand for high quality illuminated masterpieces from private clients and institutions; see for example The Almanac Hours, illustrated by the Master of the Breviary Monypenny, sold at Christie’s in July 2020 for £ 1.63 million, as well as secular works in vernacular language such as John Lydgate’s The Fall of Princes in old English, sold by Christie’s in July 2018 for £ 392,750, or Noël de Fribois’s Miroir Historial in old French, sold by Christie’s in 2016 for £ 470,500. Conditions and provenance are more important than ever.” he confirms.

Interestingly, it is not always necessary to commit large amounts to obtain significant antiquarian books. The historic Gonnelli auction house in Florence was offering rare pieces for a few hundred euros early this month. First editions of classics from Kafka to J.D. Salinger at recent Sotheby’s auctions sold for a few thousand dollars; a numbered first edition of Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince from 1888 sold under £ 30,000 in 2017 in London. In the session “English Literature, History, Science, Children’s Books and Illustrations” at Sotheby’s London a few days ago, ancient manuscripts were sold with a starting price of a few thousand GBP.

How to approach ancient books for the first time? To understand more of this field and to depart from the mere conversation about collecting, we met Giancarlo Petrella, a scholar of ancient books at the University Federico II of Naples and director of the first course in Italy dedicated to the history and conservation of the book heritage.

Why do you think someone should be fascinated by ancient books today?

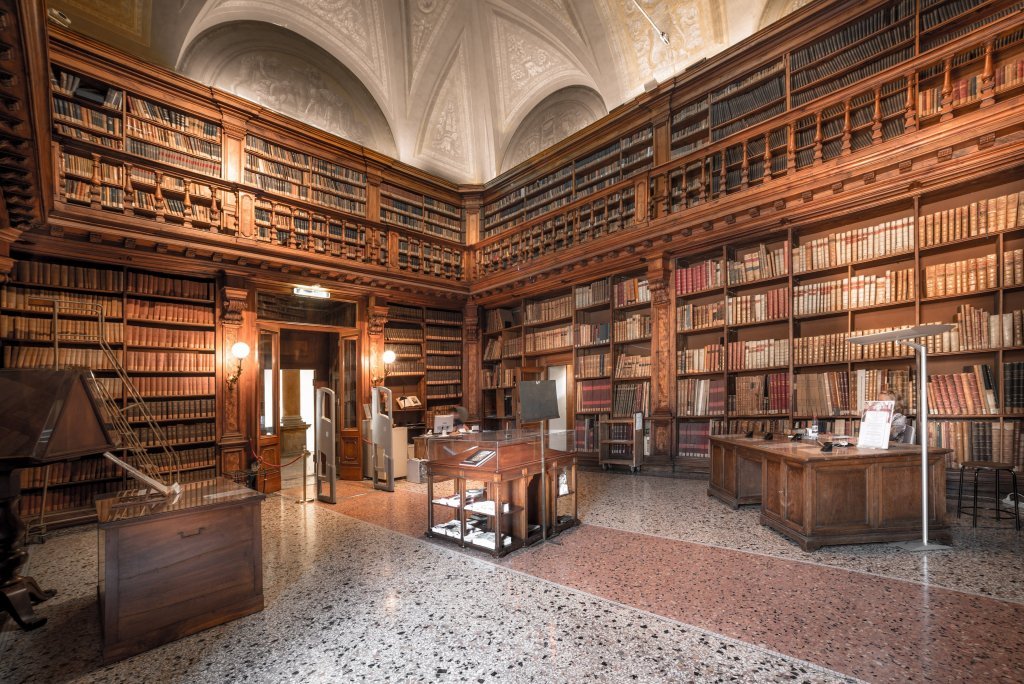

The first reason has to do with their aesthetic value. The first approach to an ancient book is to the object itself, visually and haptically speaking. I deal with books from the second half of the 15th century and the 16th century, which are some of the best expressions of human craftsmanship. Today’s Italian best manufacturing can be traced back to ancient books. The first product to be extensively exported across Europe was the printed book, which was invented in Germany in the mid 15th century and later perfected in Italy. For one and a half centuries Venice and other Italian cities were the centre of the market for these objects, producing books that were appreciated for their beauty beyond borders. This history explains why we find Italian books from the period in the main libraries of collectors all over the planet, from the Japanese who still collect incunabula today, to American ones. For example, the major oil and steel capitalists in the 19th century US would collect Renaissance books to give themselves a cultural standing, ennobling their economic position. Among them was J.P. Morgan, who acquired some of the greatest book masterpieces of the 16th century, preserved today at the J.P. Morgan Library in New York. The collection is now one of the most stunning in the world for ancient Italian volumes, including first editions of Dante, illuminated books from the Renaissance and the first editions from the workshop of Aldo Manuzio. These pieces are so charming that they transformed businessmen like Morgan, Paul Getty, and their descendants into ravenous collectors.

What does “beautiful” mean in the context of ancient books?

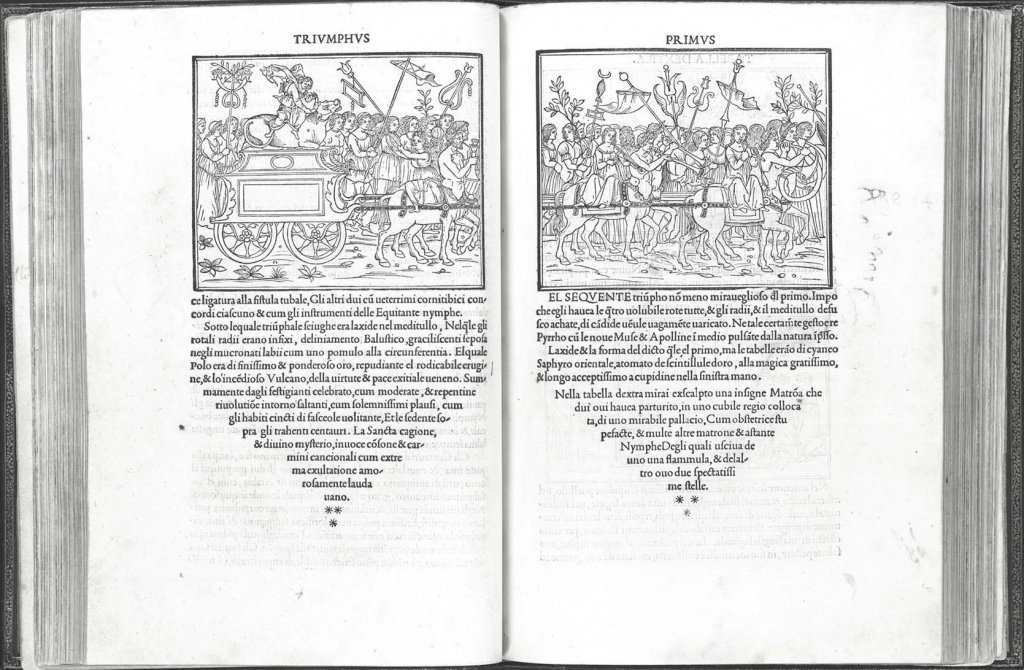

I can try to explain it with an example. One of the most beautiful books of the Italian Renaissance is the so-called Poliphilo, that is the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, printed in 1499 by Aldo Manuzio. Today it is a fairly well-known book in popular culture too thanks to Umberto Eco, who analysed it extensively. The Poliphilo is one of the first fully illustrated books, with images that stylistically refer to the great Venetian painting and engraving traditions of the late 15th century. This book is especially interesting for the relationship between text and image in it. It tells the story of a dreamlike love journey, accompanied by engravings with rich iconographic and symbolic syncretism: the images show the influence of classical culture, but also of the Kabbalah and hieroglyphs. The Poliphilo was one of the books that immediately fascinated its contemporaries. Many wanted to own it immediately but not in order to read it. With its mixture of Latin, vernacular and macaronic, the Poliphilo is actually almost impossible to read. The contemporaries bought it for its aesthetic beauty instead. For example, the bibliophile Jean Grolier, Viscount d’Aguisy was one of its earliest known collectors. Active at the beginning of the 16th century, Grolier personally met Manuzio (who died in 1515) and was one of his first customers. He certainly bought three copies of the Poliphilo, perhaps five, just for the pleasure of having it in his hands. Today Grolier is considered the forefather of collecting this book, which is present in all the most important book collections in the world, from that of Paul Getty to J.P. Morgan to Annalisa Feltrinelli and Umberto Eco. The Poliphilo, which today reaches prices of a few hundred thousand euros depending on the conditions of the volume and the previous owners is a good example of beauty in the context of ancient books. It is an extraordinary object in terms of composition, the balance between text and image, the very refined typography (a rounded font specifically made for Manuzio by the punchcutter Francesco Griffo). Moreover, the aesthetic beauty of Poliphilo is coupled with the histories of each existing copy, those tales that go beyond what is printed in it.

What kind of tales are hidden behind an ancient book?

Multiple traces have settled on the pages of ancient books over the centuries: signs that transform the study of a single copy into a detective novel. Like a crime investigation, it is about collecting clues to be deciphered towards the answers. Let me explain further. Ancient books have always been “scribbled” by their different owners and readers throughout their history. These traces are like the notes we leave on the margins of our paperback books today. They reveal many aspects of the culture at the time. To give you an example, I just came across one of the first printed editions of Ptolemaic geography from the 1470s, accompanied by about thirty maps of the then “known world.” These types of editions constitute the first atlases in human history. Between the 15th and 16th centuries, an anonymous reader added footnotes on this specific copy. Every time they read a familiar place in the text, they listed other books about it and put notes on their personal travel experiences there, supplementing the text with corrections and impressions. Through this book and its annotations we can then reconstruct the library of an erudite geographer of the late 15th century, know which books they had at home, which ones were available for consultation, how the evolution of knowledge progressed over the centuries, intertwining with the knowledge of other readers. This is one of the most fascinating aspects of ancient books: they should be understood not only as fetishes and artifacts but also as witnesses of time.

There is more pleasure in reactivating the content of ancient books than simply owning them.

The proper word to render the concept is “hypertext.” The value of a book is not only the information printed on the pages, but also the historical context and the meanings around it. We now think that hyperlinks are an invention of the 20th century, but that is not true. The Ptolemy I mentioned earlier is full of them. The reader created external references by adding notes linking other authors, for example Livy, Pliny, Flavio Biondo, or countless other medieval sources. Today we as scholars have the task of opening those links and discovering which authors the 15th century reader knew at that time. From a methodological point of view, the study of annotations is the most compelling aspect not only of the history of the book, but also of cultural history in general. It is from annotations that the context is deduced: its culture, the circulation of ideas and how they formed.

You refer to the history of books as the starting point of cultural history.

Also intended as objects, books are necessary to study cultural history. It is important to understand how they were read (history of reading) but also how they were bought (history of collecting). After 400 years, books that have ceased to carry out their communicative function are back in vogue because wealthy collectors in the 19th and early 20th centuries went crazy for them and began to scour the market. Thanks to collectors, many books that were forgotten in libraries came back to life, following a taste for them and rediscovery of their history.

What role does rarity play in the charm of a book?

To make a comparison, think of endangered animals, a Siberian tiger for example. We are shocked to know that only a small number of them still exist today. There are cases in which a single copy of a particular edition still survives, not to mention that many editions are extinct. For example, thanks to historical sources we know that the first edition of Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato was printed in 1482-83 in Reggio Emilia or perhaps in Scandiano, but in reality no one has ever seen a copy of that edition. Sometimes it happens we discover the only copy of an edition previously unknown, hidden somewhere in libraries or found on the market. Rarity has an impact on the historical value and consequently the monetary value of a book.

What do you think of the reception of ancient books beyond their niche?

At least in Italy, the vast majority of people are completely unaware of the amazing heritage of ancient books that exists even in smaller public libraries. Some time ago, a research on a typographer from Northern Italy led me to Nicosia in Sicily, a small village with an almost forgotten library. With great surprise there I found many books from the 15th and 16th centuries, coming from the nearby convents that were shut down with the unification of the county. There is no need to visit the National Library of Florence or the Marciana Library in Venice — the two most important Renaissance book collections in Italy — to find book gems from the period.

How can one appreciate this heritage without being an expert?

If they were given more resources, schools and libraries should organize more book exhibitions, which is the only way to learn about this heritage. Unfortunately books are considered less exciting for viewers than artworks, which are thought to be more easily appreciated even without any knowledge of art history. Visually speaking, artworks seem more straightforward than books. Moreover, a book on display cannot be seen in its entirety as it happens for an artwork or a design object. A book requires a greater effort than artworks on the part of exhibition organizers in helping accessibility and implementing an effective learning experience.

Exhibitions of ancient books rarely target the general public.

This point hurts me, as it shows a disregard for the general public by certain libraries, especially those where the generational turnover has been slow. As a professor, I have by now contributed to forming at least a generation of future librarians. These are highly competent people who nonetheless are unable to enter the ranks of libraries in the country, as there have been no open calls for stable jobs in decades. In general, the Italian situation in respect to book heritage seems marked by close-mindedness and lack of proper communication, both on a national and international level.

Could ancient books, with their diverse nature, be a driving force to bring different audiences together?

Yes, I think so, especially when it comes to design. The Renaissance book is in fact the first design object in Italy. More or less consciously, many great graphic designers of the 20th century were inspired by the layout of the Renaissance book, which is based on precise rules such as the Golden Ratio, the close relationship between white and black parts and between images and text. The history of Italian and European graphic design began with the foundries and typographies of the Renaissance. For example, the 19th century Pre-Raphaelites drew heavily on medieval Italian culture from the 14th and 15th centuries. They were so close to Italian book culture that their leader William Morris founded a publishing house dealing with books based on the aesthetic canon of the 15th century Italian incunabula. Even beyond the Renaissance, one can think of the 1970s newspapers using Bodoni’s fonts (18th century), just like the late publisher Franco Maria Ricci did with his initials FMR for his art magazine. If we look at the niche publishing of the last decades, there have also been practices that have their roots in the 15th century. For example, Alberto Tallone from Alpignano near Turin produces books in very limited editions and holds a small catalogue, since he still uses 17th century movable characters, original inks, and top quality papers produced in Amalfi, Pescia and Japan. His books are the true reenactment of Renaissance craftsmanship.

December 17, 2020