In memory of Herman Daled, beyond his collection

A few weeks after his passing, we delve into Herman Daled’s seminal involvement with art, an engagement that went much beyond collecting.

I am not ready to give up the fight to not be considered a collector, as I have never felt like one.

Herman Daled, Nov 25th, 2009

Herman Daled was a legendary contemporary art collector, despite his intentions never to become one. He would always consider his multiple activities in the art world as participatory gestures. His historic collection of radical conceptual works was for him but one aspect of his engagement with art. He would call it “collecte” (gather-up) instead of collection, implying a sense of wandering and chancy encounters. He would never take credit for it except for seizing the opportunities that presented themselves to him thanks to a bit of madness, he said, or “for the wrong reasons”, i.e. motivated by personal projections in the context of an era, or by his attraction for the unknown: what a beautiful bad reason! He was wary of beauty, as he thought it presupposed recognition. Above all, the artwork was for him an object of knowledge.

When he recounted his background, Herman Daled linked his profession as a radiologist and his dealing with medical images to the primacy of the sense of sight in the family culture. Sometimes he evoked a childhood memory, his ball games at his grandfather’s house among the paintings of Flemish Primitives… For a long time, he kept the Expressionist paintings inherited from his father in his medical office. With amusement, he would explain how those pictures seemed more reassuring for his patients than the works of Niele Toroni, which at one point he hung! When he was asked to speak about how he first got involved in contemporary art, he always mentioned Albert Claude, Nobel Prize winner in medicine in 1974 with whom he worked for six years.

On his advice, he decided to keep up with the times and made his first purchases, quite randomly, as he said, but how could it have been otherwise? Although they seemed far away from his interests after 1966, he didn’t reject them. When exhibitions of personal collections and the opening of private foundations were in the air, Herman Daled was not interested in making his “collection” public and permanent, but, he insisted, if one day the accumulated works had to be the subject of a show, he wanted the whole of it to be made visible in all its “eclecticism”, without selection. The titles imagined by him for such an exhibition that never took place, but also for the smaller one that did happen at the Haus der Kunst in 2010, were Fleurs des champs (field flowers) or Leftovers. They now remind of his approach to collecting as a stroll, or what has remained of his action. For a curator, they sound quite strange for a bunch of conceptual art, which we should perhaps stop considering so ascetic. Sober, reflective, critical, but also committed, political, sensitive, imbued with humorous touches: conceptual art resonated with Daled’s personality.

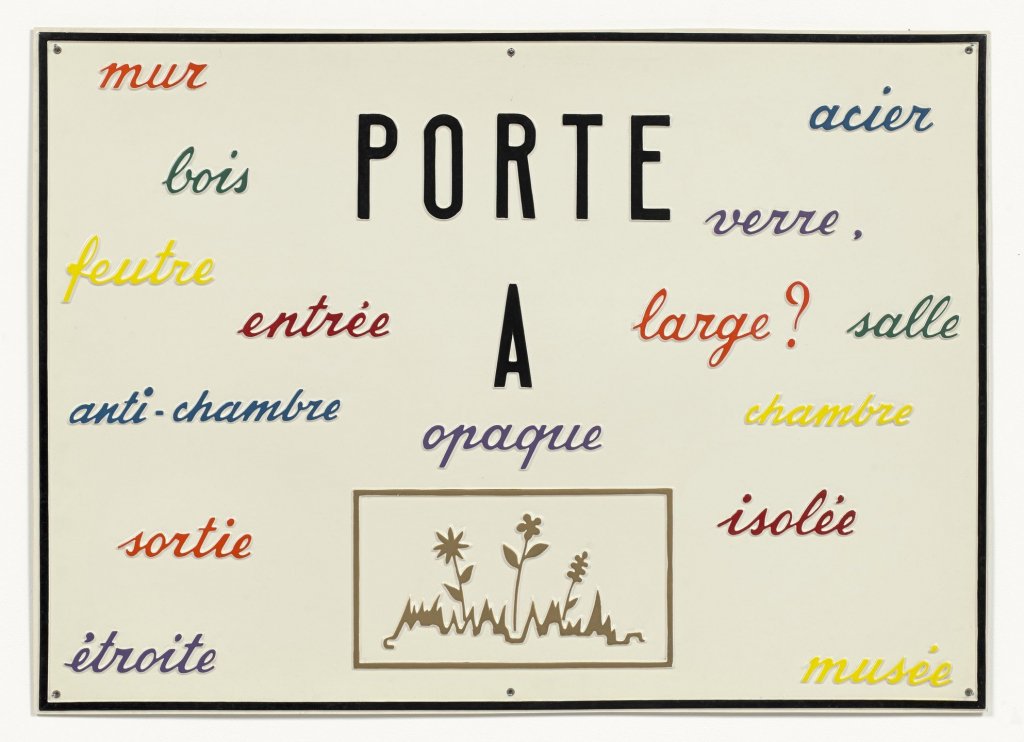

Thanks to the friendship and determination of Chris Dercon, part of the admittedly nodal collection of works acquired between 1966 and 1978 was exhibited in Munich. By accepting to focus on this period, Herman Daled wanted to highlight the role of his wife Nicole until 1977 and the seminal meeting with Marcel Broodthaers on the occasion of the purchase of La Robe de Maria. This moment marked the beginning of his unwavering support for the Belgian artist, whom he helped for the production of his famous works on plate along with Izy Fiszman. Daled was de-facto Broodthaers’ accomplice in his Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles in 1969 on the beach of Le Coq. On the other hand, the artist facilitated the relationship between the Daled’s and European and American artists, whom Broodthaers would invite to the collectors’ place by declaring: “we can drink, we can eat, we can smoke, and they even buy!”

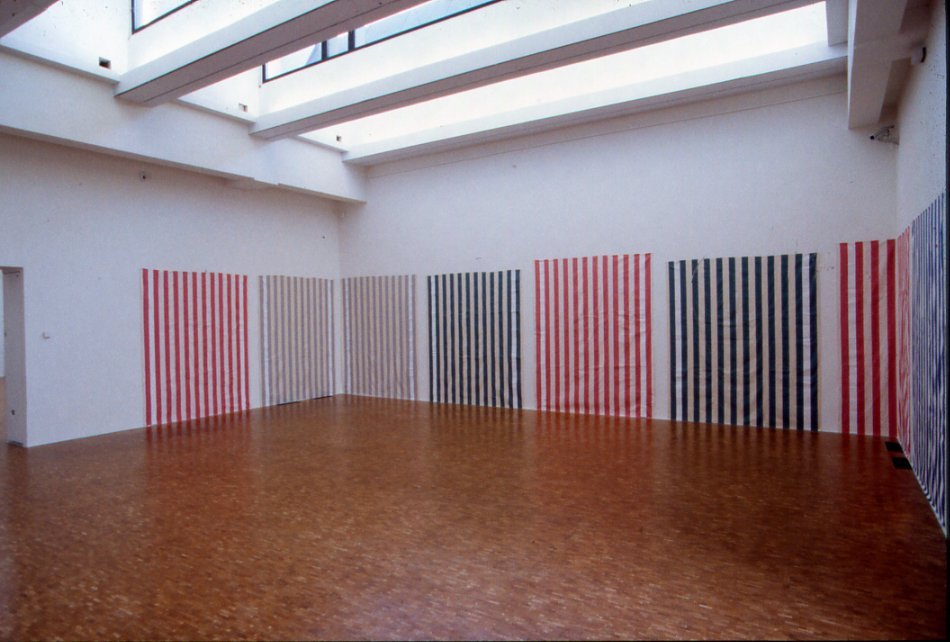

Two contracts, which he called “serious jokes”, show the nature of Herman Daled’s commitment with artists. An agreement with Daniel Buren in 1970 stipulated that the collector would only buy the artist’s canvases once a month for a period of a year. The acquisition of Broodthaers’s works was an exception, of course. Secondly, in 1972 Daled decided to buy again the same scroll by Niele Toroni for a higher price. He had acquired it two years earlier but the market had gone up by then.

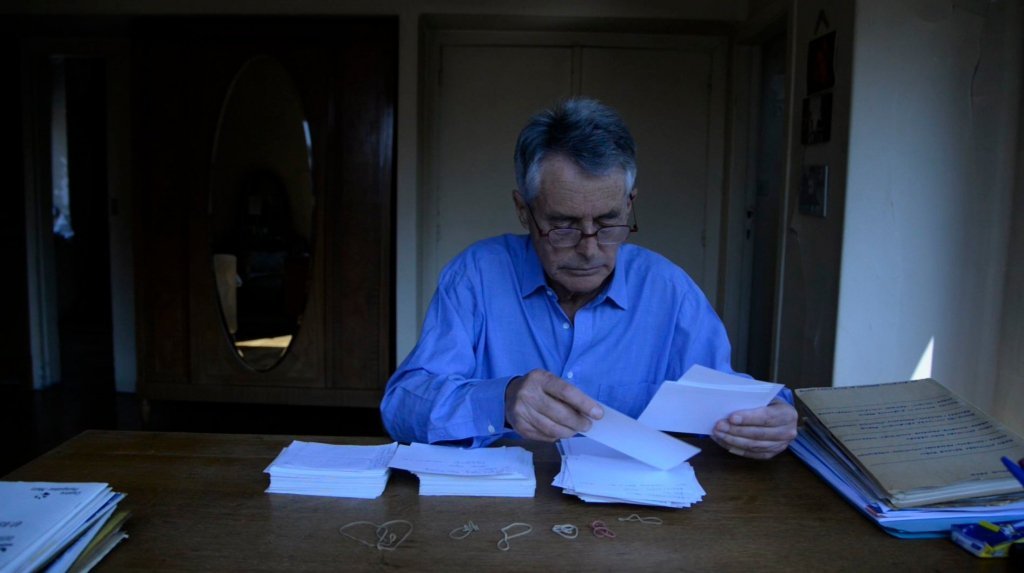

Herman Daled would always comply with the rules he had set for himself: he always acquired the works of artists during their emerging phase; he never bought at art fairs, which he hated; he never bought at public auctions; he never re-sold. Only in 2011, the works from the Munich exhibition and the archives relating to the same period 1966-1978 (invitation cards, leaflets, letters, posters, editions, photographs, press clippings, that is an integral part of the process of the artists and of the collection) were sold to MoMA in order to guarantee them a good future. The following year, he ended his “collecte”.

Herman Daled’s active involvement with contemporary art was far from being limited to collecting. He organized events and supported projects and publications. He financed Buren’s wild displays on the occasion of When Attitudes Become Form in Bern in 1969. Shortly after, he organized the performance The Singing Sculpture by Gilbert & George in the Garden Store Louise in Brussels and the TV Ball by James Lee Byars. He produced and distributed his Black Book in the Soignes forest (1971). He financially supported the alternative art space A 37 90 89 in Antwerp (1969) and the gallery 1-37 in Paris (1972-1976). He made available to artists a storefront in the Galerie Le Bailli in Brussels, where galleries were also established (1973-1975). He translated into French and distributed the The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement by Seth Siegelaub in 1971. He edited or co-edited artists’ books (Hanne Darboven, Dan Graham, Carl Andre, Jacques Charlier, Niele Toroni, Daniel Buren among others). In the Hotel Wolfers, a modernist house by Henry van de Velde he bought in 1977, he presented exhibitions (Robert Mapplethorpe, Niele Toroni, Dan Graham), publications (Joëlle Tuerlinckx), conferences (Christoph Fink), interventions (Richard Venlet), film shooting (Manon de Boer) and more. Apart from these events, the walls of this house remained empty, so that the artworks could not become mere decoration. He would however frequently lend pieces to exhibitions not to hide them from the gaze of the passionate viewer.

Herman Daled was also involved in public institutions in Brussels. From 1988 to 1998, he chaired the Société des Expositions at the Palais des Beaux-Arts. In the following decade, he was on the Board of Directors of Argos, a center for the audiovisual arts. He was also one the founders of WIELS, which he actively chaired until 2013 before being appointed Honorary Chairman [here is the link tpo our interview with Dirk Snauwaert, WIELS’ current director, Ed]. Herman Daled always carried a folded small piece of paper with him: a list of the artists whose pieces he owned. In its modesty, the paper was an exemplary object summing up the commitment of an entire life, something he would occasionally show–for example during a lecture and in the inaugural exhibition of La Maison Rouge in Paris titled L’intime, le collectionneur derrière la porte in 2004, which created a stark contrast with the partially reconstituted interiors. This paper list evoked Herman Daled’s attachment to the people he met more than to the objects he gathered. As those who knew him can confirm, his generosity was only matched by his discretion.

December 23, 2020