Tarot cards: the pocket-sized Renaissance

First recorded in 15th century Italy, tarot cards have reached today’s collections following strange paths and through a few discoveries.

The suspense of choosing a tarot card is always so great. Time stops when we don’t know whether a hanged man or an emperor will appear before our eyes, revealing our own destiny to us. So long, the kiss of fortune. Tarot cards were originally called “triumphs”. The first packs were recorded in 15th century Italy and were traditionally made up of 78 cards, organized in four suits. The 22 “superior” cards without suits are now called major arcana.

Smaller and bigger decks also existed, for example in German-speaking countries or the funnily-named 97-card deck Minchiate (bullshit) from Florence. The latter was first mentioned in a very authoritative letter written by Luigi Pulci to Lorenzo de ‘Medici in 1466. Pulci was a very serious Renaissance court poet, but also a great parodist and Tuscan “bullshitter.” The term “minchiate” probably derives from the Latin word for male genitalia, perhaps pointing to the fact that the game was seen as but a simple pastime.

However, some must have considered it a very refined entertainment too if they were ready to spend fortunes to purchase fine decks. For example, in 1440 Giusto Giusti, a notary of the Medici’s and an important intermediary in the negotiation of contracts for mercenary troops, wrote in his diary: “On Friday 16 September I donated to the magnificent Lord Messer Gismondo a pair of Naibi triumphs, custom designed in Florence with his superb coat of arms. It cost me 4 and a half ducats.” A fair amount indeed.

The word “naibi”, which was used in Tuscany until the mid 15th century, also reveals the Arabic origin of the cards. From northern Africa, Florence took a leading role in the production of playing cards, as Franco Pratesi confirms in his book on card games in the region at the time. Instead of what was previously believed, Florence was an important creative centre for the art of playing cards along with Ferrara, Cremona and Milan.

A careful analysis carried out between 2004 and 2005 by Cristina Fiorini, and previously by Luciano Bellosi, shows how the famous Rothschild deck is attributable to the Florentine artist Giovanni di Marco, known as Giovanni dal Ponte. These cards were part of a pack created in Florence around 1423. In addition to the eight cards (including one tarot, the Emperor) kept in the Rothschild Cabinet of the Louvre, the deck also includes a knight of swords now preserved in the art museum of Bassano del Grappa. Long considered coloured woodcuts, these nine cards are in fact examples of the dynamic drawing style typical of Florence at the time.

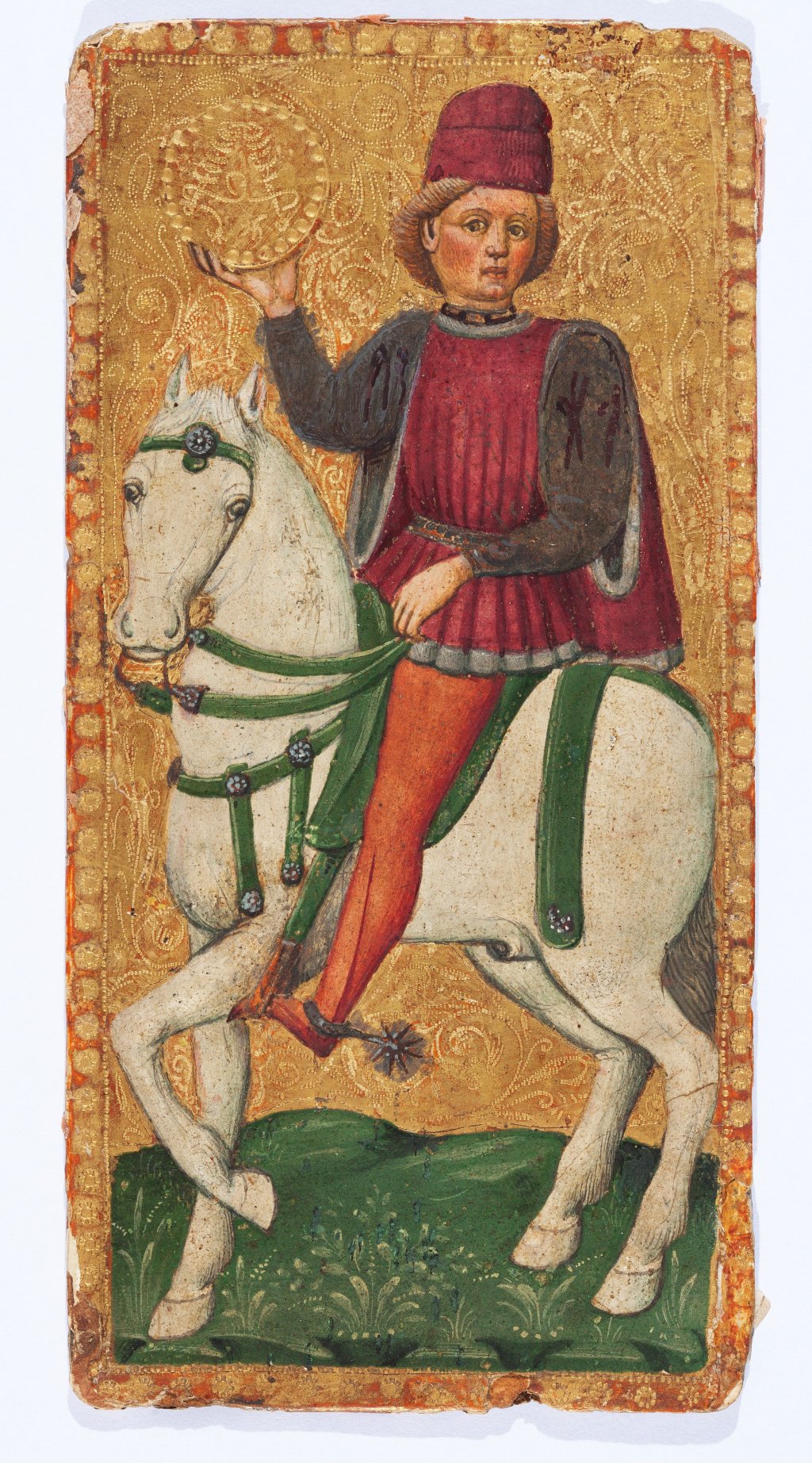

Renaissance tarot cards are not ordinary cards. They are large, rarely smaller than 17 cm in height. Even though they are made of simple plastered paper, they have refined gold leaf backgrounds, frequently stamped with a punch to form decorations of flowers and leaves, scrolls and geometric diamond shapes. They are coloured with expensive pigments, from lapis lazuli for the blues to vermilion for the reds, to the mixture of indigo and orpiment, that is the yellow arsenic sulphur crystals for the greens. The 15th century tarot cards are real miniatures, now kept safe in various public and private art collections. Their charmingly serendipitous histories intertwine with the chance of the very game they were used for.

For example, it was a lucky card indeed that which was bought in 1992 by the Musée Français de la Carte à Jouer in Issy-les-Moulineaux, a unique museum near Paris housed in a 18th century pavilion (the fairy tale Pavilion Conti) and one of major seven museums in the world dedicated to the theme of playing cards—the others being in Turnhout, Belgium, Leinfelden Echterdingen, Germany, Vitoria, Spain (the Fournier de Naipes Museum), Capriolo and Vergato, Italy.

The card acquired by the French museum has been identified as the Chariot, a figure of the major arcana and a symbol of victory and triumph. Precious as a very elegant miniature, perhaps for this reason perfectly preserved and certainly little used for actual games or divination, it has been linked to two other cards in the National Museum in Warsaw: a queen of cups and a knight of coins from the same deck.

Due to their refinement, richness of colours and the stamped gold background, these cards were thought to originate from the Renaissance courts of Ferrara. Recently, a series of new studies and the scientific work of historian Thierry Depaulis has shaken the Ferrara attribution, pointing instead to the 15th century Milanese court and artist Bonifacio Bembo and his workshop.

In the 15th century frescoes in the “game room” of the Milanese Palazzo Borromeo, tapered creatures with arcane hairstyles entertain themselves in a game of tarot cards with “exotic elegance”, as Roberto Longhi wrote in 1958 while tracing the Lombard line of art and revealing the refinement of the 15th century style of northern Italy. Longhi continues about the region: “The whole cosmos seems to reduce itself to a gilded tarot, depressed and beaten down by the short stick of the homonymous card.”

Already in 1928, Longhi seemed to have discovered the author of the Lombard tarots preserved in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan and the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo. In his essay for the magazine “Pinacotheca”, he attributed the creation of the deck of 48 cards known as “Arcani Brambilla” (from the name of the last owners) to Bonifacio Bembo, a Cremonese painter who was quick to grasp the novelties of the “outsiders” Pisanello, Gentile and Masolino, as well as the contemporary styles from Padua and Ferrara.

Bembo was the head of an amazing workshop and one of the protagonists of the vibrant art scene in mid 15th century Cremona. With sublime chic, he would insert in the tarot cards for Filippo Maria Visconti the symbols, emblems and mottos of the dukes of Milan. The three “Visconti di Modrone” tarots kept in the Beinecke library of Yale University are also usually traced back to Bembo, yet in 2013 Sandrina Bandera, curator of an exhibition on Bembo’s tarots, cautiously advanced a new attribution: his father Giovanni or even another artist from the same scene.

Other stories intertwine for the tarot cards of the Accademia di Carrara in Bergamo. There, the Colleoni deck, also by the Bembo workshop, was divided up in the 19th century because of the ambitions of the owner, the descendant Colleoni, who was eager to own a piece by Fra’ Galgario in the hands of the Baglioni counts. Just like lost gamble, the Baglioni tarot cards ended up in Bergamo a little later, while the Colleoni deck was sold to the Morgan Library in New York with a fair profit.

Another tale from 2009 has a happy ending instead. The complete Sola Busca deck, named after the owners the Marquise Busca and Count Sola, was purchased by the Italian Ministry of Culture for the Pinacoteca di Brera. It is the oldest complete deck in the world. It bears an enigmatic iconography, a testimony of the alchemical-hermetic knowledge so dear to the humanists at the time. The basilisk, the mythical creature with the body of a rooster and the tail of a snake – the indispensable maker of gold – crawls among the cards of coins, alluding to the opus alchemicum. The deck is still of very difficult attribution. Some mention Squarcione, master of Mantegna, others Marco Zoppo and Giorgio Schiavone, or even the Ancona-based Nicola di Maestro Antonio.

Through these tangled paths of artists and owners, the Lombard tarots have undergone troubles worthy of the most dramatic love story, but surely they have also become the shimmering materials for masterpieces of combinatorial fantasy such as The Castle of Crossed Destinies by Italo Calvino, where tales born from the succession of the mysterious figures from the Bembo tarots reassemble into infinite labyrinths.

Notes Calvino: “When I was studying the symbolism of the tarot cards, among the many readings, it was the strange book Histoire de Notre Image by André Virel that provided clear ideas.” Calvino would not hesitate to define it as the work of a madman. It is no coincidence. The odd can sometimes be the most insightful, given we keep ourselves upside down like the Hanged Man of the tarots, waiting for the urgent breakthroughs we seek to find.

January 1, 2021