Digital old masters in actuality

Digital old masters are a thing now more than ever, but much is still to be learned. We look at how they do it in Amsterdam

It’s been almost a year since people in the West had to get familiar with the word “lockdown.” From a dream of desirable comfort, the concept of working from home has turned into the nightmare of seclusion. Everyone has joined the generation Netflix. Museums had to follow and now digital old masters are a thing more than ever. At the end of the day, if those artworks were pleasing millions of physical visitors every year, why shouldn’t they do so online? Or so the argument goes…

[Here is our letter to Italian museums about their online future. Ed.]

This article is not a full picture of the current state of what’s available online of old master paintings. Google Arts & Culture and the digital presence of massive institutions like the Met already give a good idea. We instead focus on the city of Amsterdam, one of the top tourist destinations in Europe before the pandemic, a city with high class art museums that seem especially up for the challenge of turning the physical into digital. We give some insights from behind the scenes, reporting on the work of so-called “digital teams” in large art institutions. We also add testimonies from a couple of those firms that provide the technical infrastructures for this digital apparatus, that is, the bricklayers behind the digital museum building.

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is arguably the temple of painting from the Dutch Golden Age and nearby eras, a period marked by blockbusters such as Rembrandt, Bosch, and Vermeer. Before the pandemic, the museum could count on 2.7 million visitors a year, a bit more than its Italian Renaissance counterpart and other heavyweight in the battle of ancient art museums, the Uffizi in Florence (2.3 million). We learned about the Rijksmuseum’s digital old masters from Nanet Beumer, the head of the institution’s digital team. Her online program is ambitious and motivated by a true conviction that information should be accessible to everyone – in her previous job she was working on digital tools to share financial information with the general public.

Beumer confirmed that the digital team was still to be formed when she joined the Rijksmuseum in 2019. This doesn’t mean there was no online content from the museum. The major digital initiative of the Rijksstudio (all the collection available online) started many years earlier, but it was the work of scattered expertise in the institution. Her first challenge in the new job was Operation Nightwatch: the online coverage of the restoration of Rembrandt’s most famous painting. Right now, the digital team run by Beumer comprises 6 people, including 2 content producers and 1 social media manager. She continues: “The first aim was to make art available with high resolution images for everyone to enjoy. Afterwards the focus changed to interaction, which means the online user should get to know the collection better. Now we are aiming at engagement, that is liking our videos, commenting on our posts, etc. The direction should go from awareness to engagement.”

Like for all the other museums in the world, the number of online visitors of the Rijksmuseum has increased dramatically since the beginning of the pandemic. Yet Beumer reminds us that the lockdown is only one of the reasons for museums to exist online: “Not everyone can go to a museum. People might not be able to afford it as they live too far for example, or they might be sick.” As to Covid, Beumer says that from a surprisingly long “time-on-page” seen in the first March/April lockdown, things slowly came back to the typical short attention span of digital surfers. For this reason, the museum has recently launched “Rijksmuseum in 60 Seconds,” short videos about single topics or artworks.

For museums, we believe there is also the question of snackable content and its possible incompatibility with the scientific rigour these institutions are supposed to have. Quantity rules over quality online. If the digital universe is famous for its distracted dwellers – hence the success of the dogma “the easier the better the more” – can museums still manage to keep their role as knights of culture? Beumer is optimistic: “The content we already made in collaboration with academics shows us that the general public is also interested in the scientific aspects of art or the less famous items in the collection. What counts is the story behind these facts and items.” She mentions National Geographic as one of her models for online storytelling.

Aside from the Rijksmuseum, the other heavyweight art institution in Amsterdam is the Van Gogh Museum: the second usual suspect for insights into digital old masters. Although not as popular in terms of real visitors as its neighbor (data from 2019), the museum dedicated to the famous 19th century Dutch painter can boast an impressive amount of Instagram followers (1.8 million) and Youtube subscribers (31k). To give a sense of scale, the most visited museum in the world, the Louvre, has only about twice as many. This shows the great effort put by the Dutch institution into its online presence. We reached out to the head of the digital team of 8 people, Martijn Pronk, a lawyer with experience in legal publishing and formerly at the Rijksmuseum.

Pronk told us that his aim is to integrate the museum website and its social media into one big digital Van Gogh world to connect with fans. He seems especially proud of the brand new website, launched last year: “It now features more ways of inspiring people with Van Gogh’s life and work. All paintings, drawings and letters in the collection are now online and visitors can zoom in as far as the brushstrokes on the artworks. Improved filters now make it easier to search the collection of paintings, drawings and letters, and more information about each item is now available. For example, visitors can see which paintings in the collection are currently on display at the museum (unfortunately the museum is closed at the moment, due to government regulations to tackle the coronavirus). The new Vincent for scale functionality shows the size of a painting compared to the height of Vincent van Gogh, who was 1.64 metres tall. The new website also features short, engaging stories, reminiscent of the stories on Instagram and Facebook.”

Just like the Rijksmuseum and many other museums, the Van Gogh Museum works in close partnership with Google Arts & Culture, which at the same time provides the institution with grants. Pronk continues: “People can find us on Google Arts & Culture for a virtual tour of the museum, or they can check our Youtube channel, where virtual tours are accompanied by music by Nozem especially composed for them. For Youtube we also made a special virtual reality tour of our exhibition on show at the time, called In the Picture. On our website, visitors can also find a page called “Bring the museum to your home” where they can read Van Gogh’s letters, find coloring pages of his most famous artworks, and learn more about our apps.” As to the question of scientific rigour vs snackable content in relation to digital old masters, he says: “Our “snacks” are scientifically correct. The important thing is to not mix various contents aimed at various groups in one place, but present the right content in the right place to the right people.”

Lastly we come to the infrastructure for digital old masters. Two Dutch companies, Q42 and Micrio (the latter developed by the former), provide the technology necessary to build compelling online experiences for museums. For example, Q42 developed both the Rijksmuseum and the Van Gogh Museum’s websites. Erwin Verbruggen, a project manager in charge of the development of the newest Rijksmuseum’s site told us that the task was to combine many different ways to tell a story about the collection, but also combine them into a series. People should swipe through them as they do on Instagram for example. As Beumer also confirms, if the first bold choice of the Dutch institution was sharing its full collection with the Rijksstudio in 2012, the current question is how to take it further.

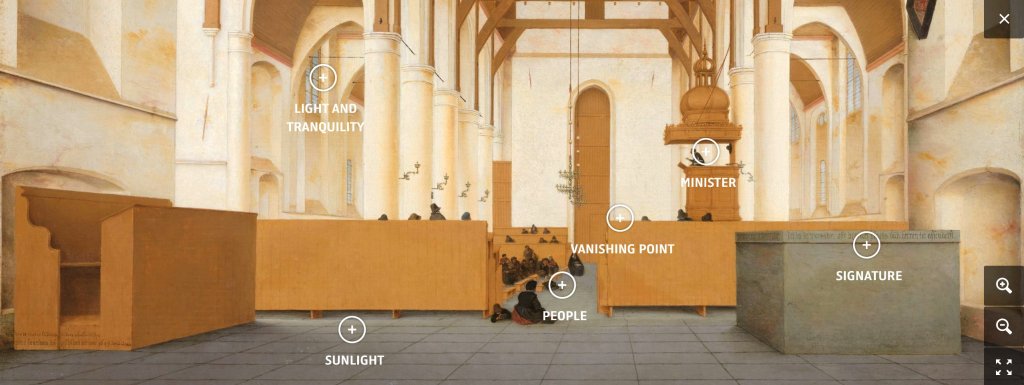

In this regard, accessibility is key and this is where Micrio comes into play. Micrio is a platform that allows easy navigation and annotation of hyper resolution images. We talked to its founder Marcel Duin to ask about the challenges of digital old masters in this context. From a technical perspective, Duin mentions that when it comes to hyper resolution photography of artworks, storing and sharing are both big issues. On the one hand, storing doesn’t only mean the physical possibility of stocking large amounts of bytes, but also the necessary tasks linked to proper photography such as color correction. On the other hand, sharing these images is easier said than done. The online world is especially fluid. Browsers and hardware become quickly obsolete, not to mention that not everybody has the privilege of high speed internet connections. In this regard, Micrio was especially created with the intent of making sure hyper resolution images are accessible to all. It is now a technology used by the Riijksmuseum in connection with brand new content inserted as annotations by academics on spectacular images that please the general public. Digital old masters again show how the snackable and the rigorous are not mutually exclusive.

[For uses of Micrio technology for contemporary art projects, check the online exhibitions Global Cows, Francesco Clemente, and Andrea Romano. Ed.]

February 17, 2021