To the zodiac and back

Phaethon changes sex, the gods are sick, the Earth is burned, the seas are drained: the zodiac is all these turns and more

“The great and official myth concerning the Galaxy is Phaethon’s transgression and the searing of the sky in his mad course.” This is where the erudite Giorgio de Santillana finds the mythological origin of the Milky Way and the zodiac itself.

To set out in search of the enigmas of the zodiac, one must take a step back in time. The story of the young Apollo’s scion Phaethon is told by Ovid in his Metamorphoses, but the tale is even more archaic, with references found in Homer, Hesiod, the tragedians Aeschylus and Euripides, Nonno di Panopoli and later in Apollonius Rodio and Luciano.

The story is as old as time. It is about the desire of a child to be accepted by a long unknown father. The mighty Apollo promises to fulfill each of his son’s wishes in order to prove that they share the same divine DNA, but the child suffers anyway. He feels inferior to his father, some kind of Freudian “chariot envy.” He dreams to drive the famous Apollian chariot to the sun, a task that is but a piece of cake for his godly father.

Phaethon fails of course. The horses approach the dangerous constellations of the zodiac but Taurus and Leo come to life when the chariot runs nearby, turning from simulacra into threatening creatures; Scorpio exudes black poison and Phaeton no longer controls the horses. The result is catastrophic. No constellation remains in place and the Earth is burned, the seas drained. The mountain ranges emerge, the blood boils.

Atlas is forced to prop himself up on his knees to support the misaligned and burning weight of the globe on his shoulders. Desperate, Mother Earth clamors for Jupiter to intervene without delay. The father of the gods hurls his darting bolt at the child, causing an atomic explosion. The parched Phaeton falls, drawing a wide trail of smoke, until the river Po welcomes him in clouds of vapors.

The zodiac and cataclysms

According to one interpretation of this myth, Phaeton’s story is the recounting of some terrible natural phenomenon: the crash of a comet, or a meteorite, whose deadly impact would have even tilted the earth axis or killed the dinosaurs. A plausible theory, this naturalistic explanation instead complicates things. In classicism, and later in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, gods, humans, nature and cosmos intertwine.

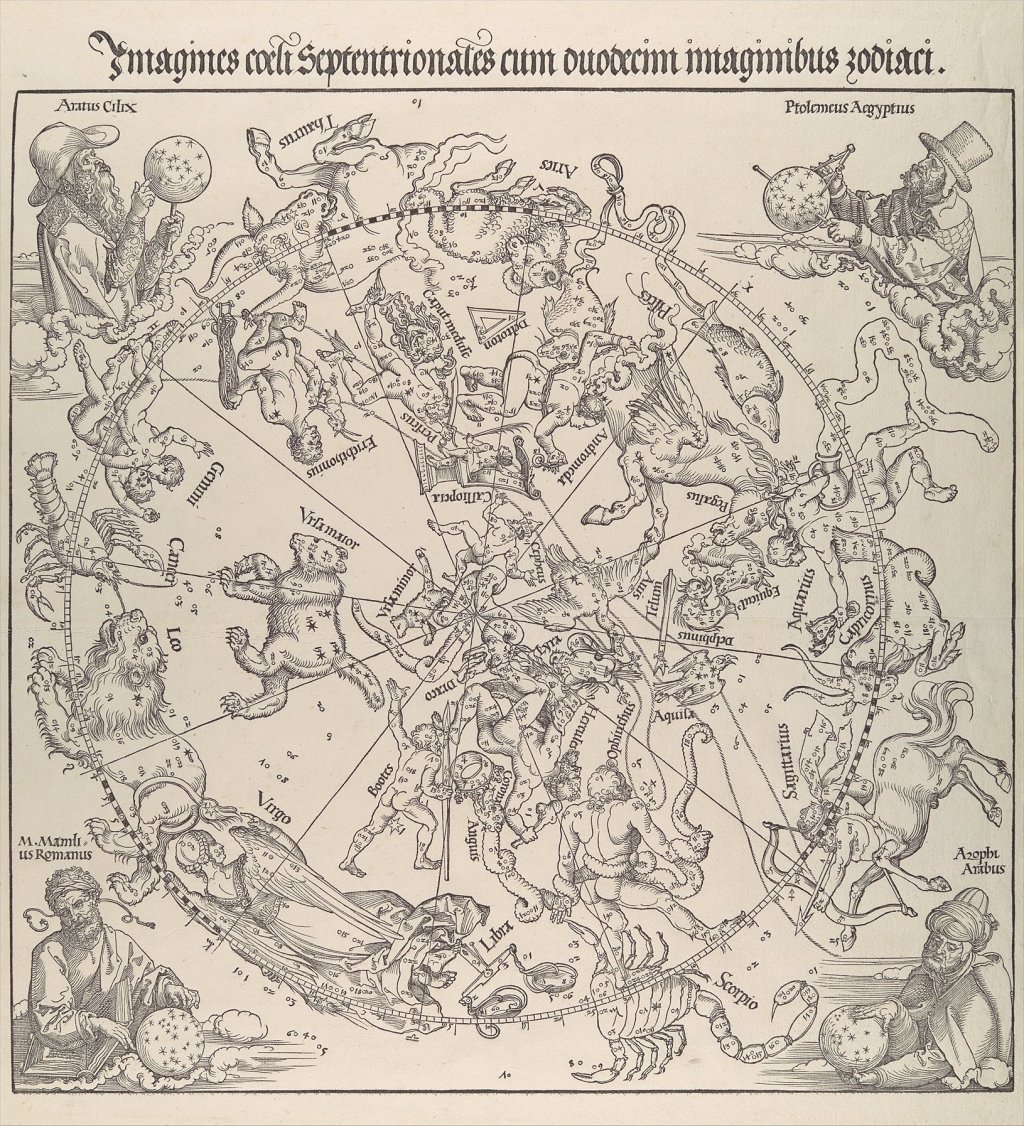

The physical and the mythical converge to form new intricate worlds. The sky maps at Palazzo Farnese di Caprarola and in the Sala Bologna of the Vatican Palace, extraordinarily similar to each other, as well as the one in Palazzo Besta in Teglio in Valtellina, provide some clarity.

The Caprarola celestial vault is a wonder of lapis lazuli, a blue sky dotted with stars and populated by not less than fifty figures of the zodiac constellations. Their author is still unconfirmed. Painted between 1571 and 1575, the artwork might be the effort of Giovanni Antonio di Varese known as Vanosino, who is also believed to be the creator of the astrological fresco of the Sala Bologna in the Vatican.

The celestial planisphere is enclosed by two elements that are not included on the list of the zodiac constellations at the time. In the top left corner Zeus throws a lightning bolt; opposite side, Phaeton crashes on the river banks of the Eridano river (the Greek name of the Po river).

This depiction of the river, elevated to a swarm of stars, changes the very celestial order. De Santillana proposes a fascinating justification for the transformation: the river functions as a connection point between the Northern world and the world of the dead. Phaeton is the bridge, the messenger of the gods. The Po river and Phaeton are instead the gods’ original sin, like Adam and Eve are the terrestrial one’s. A new world is born from them, whether good or bad.

Phaeton is a woman

Because of his titanic yet ruinous undertaking, it is commonplace to think of Phaeton as an impudent, heroic, young male. However, in the most ancient celestial iconography Phaeton changes sex and appears in female form.

In the Renaissance residence of the aristocratic Besta family of Teglio in Valtellina, in a cycle of frescoes probably from the 1540s, an anonymous artist takes up a suggestion from the Astronomicum Caesareum by Petrus Apianus. The painter depicts Phaeton swimming in the waters of the river Eridano completely naked, in unequivocally feminine features.

In the two Venetian editions of the Astronomicon by Igino (1482 and 1485), Phaeton is also depicted as a naked girl lying in the water. There is some lightness to this figure, as the abrupt fall from the sky was quickly forgotten.

The natural and phlegmatic gesture of her foot slapping the water, the arm resting on her head, the wide buttocks supported by the soft marine mattress make her resemble the Hermaphrodite, a Roman sculpture of the 2nd century BC inspired by Hellenistic models and uprooted in Rome in the 17th century.

Before Phaeton disappears from the sky in the new atlases and related astral maps, there is another important epiphany of his/her celestial myth, an epiphany that happened in the Ferrara workshop during the rule of the Este’s. This is the astrological cycle of Palazzo Schifanoia commissioned by Duke Borso, to which Aby Warburg dedicated one of his seminal studies.

The zodiac and hidden symbols

Warburg began his studies on the zodiac, gods and the astral demons in the early 20th century. He wanted to demonstrate that the ancient Olympic divinities were still present in the Middle Ages, though in disguise, subjected out of necessity to the service of astrology. Their survival coexisted with the prevailing Christianity, which would fight against their “pagan lies.”

When Warburg enters Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, more precisely the Sala dei Mesi (hall of the months), he identifies the Olympic divinities wrapped in 15th century clothes, semi-dark regions of astrological superstitions in an ambiguous alliance between logic and magic.

The months and the Decans occupy the upper and middle parts of the great astrological calendar of Schifanoia, one of the most important pictorial cycles of 15th century Italy. The philosophical research for this artwork was entrusted by Borso d’Este to the astrologer and court librarian Pellegrino Prisciani.

Artists of the Ferrara school were called to paint it: from Ercole de ‘Roberti to Francesco del Cossa, perhaps even Cosmè Tura. In the third Decan dedicated to the month of April stands a giant with large boar tusks and a snake. The dark blue background highlights the figure, and the impeccable perspective construction, derived from the Cossa lesson and Piero della Francesca, makes even the most unlikely and visionary details plausible. A white horse is behind the black colossus, a dog with a hare face is at his feet.

The giant was interpreted as a moral allegory of debauchery, transforming humans into sinners. Warbug’s critical intuition gets rid of this interpretation, demonstrating that the figures of the decans are instead the mythical gods in exile, rescued in the Middle Ages by the divinatory culture of Arab origin, which in turn had taken them back from the Astronomica di Manilius in the 1st century AD, but dating back to Chaldean and Egyptian religions.

Looking at these decans and following Warburg is to slip into a toboggan of decoding: the white horse is actually Pegasus, the hare/dog is Orion, the coiled snake is the Eridanus in its astral version. Those boar tusks allude to the myth of the Hyades, the stars of the constellation of Taurus that dominate the month of April.

The zodiac and the plague

The relationship between art and astrology is full of plagued figueres too. For example, another giant at Schifanoia advances with open arms, while devastated by the pustules of a disease that disfigures soul and body. The man proceeds, his arms open as if to hug anyone on his path in some kind of contagious brotherhood. Here no one can hypocritically look away, the young man is notre semblable, notre frère!, our neighbor, our brother.

Should we blame the stars for his doomed existence? His head is dominated by a celestial sphere with the zodiacal constellations: this is a warning of how many misfortunes, how many malignant proliferations occur due to a bad astral conjunction.

According to the medical prophecy of the magician and astrologer Ulsenio, the 1484 misalignment of Jupiter and Saturn paved the way for a late 15th century pandemic. The Syphilitic, an engraving from 1496 Albrecht Dürer made for the astrological publication by Ulsenio about the syphilis refers to this celestial threat written in the zodiac, a work that falls within the sphere of predictions from the great conjunction of 1484.

Looking at the work by Dürer, the ulcerated man comes across as a synthesis of late-Gothic elements of Germanic style, from the shape of the headdress complete with a triton-shaped plume, to the rigidly folded clothing of the mercenary lansquenet, to which naturalistic lenticular effects of pustular markings are added.

In this figure, Dürer represents the demonic influence of pagan deities according to medieval conventions, but it is only a residual trace, a recessive gene. The ancient gods will rise again without the need to hide in the zodiac and appear nefarious. That is what Renaissance was all about.

“The Olympic side of antiquity had to first be torn from the traditional demonic side by force,” writes Warburg in the introduction to Mnemosyne. “The era now, in addition to the rediscovery of the word of antiquity, also required a stylistically appropriate organic perspicuity in the external appearance.” Already in the Dürerian Melancholia I of 1514 one can see the emergence of the ancient tradition reinterpreted in the light of the magical Renaissance esotericism of Marsilio Ficino.

The zodiac and Raphael

To be under Raphael’s sky is how one should feel looking up at the fresco of the Prime Mover (1508) in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican. Shame that the more famous and classic School of Athens painting attracts more of the attention of those in the room. Indeed the Prime Mover is more secluded, relegated to one of the corners of the vault. It might nonetheless be the first scene ever created by Raphael in the Vatican, and the one that keeps the room and project together.

The Prime Mover is a female figure, the Muse of astronomy. She’s dressed in a warm green tunic embossed in the gold of the fake fresco mosaic. Urania is her name: the divinity who, bent down, gives impulse to the celestial sphere as an Aristotelian “motionless engine.” The core is the darkest globe of the Earth, which opens wide as a fertilized egg in the starred sky.

With the raised hand, she draws attention to a precise moment, October 31, 1503, where the stars aligned and Julius II became pope. The fresco is the not-so-implicit celebration of the great client. The painting traces that union of astronomy and astrology typical of the Middle Ages, where the celestial motions are always linked to an astrological picture and therefore to the horoscope.

But there is more. Here again the pagan tradition openly marries Christianity, which is sneakily depicted as the true prosecutor of classical culture. The pontiff himself is exalted by the horoscope, allegorically personified by muses and gods, of which he, the representative of the Christian God on earth, becomes the heir. Peace is made with hellish paganism, although identifying the date in Raphael’s Prime Mover with the elevation of Julius II is controversial.

And so is the meaning of July 4, 1422, the date appearing in two twin frescoes on the vaults of the Florentine chapels of the San Lorenzo church (1419-1428) and the Pazzi Chapel of Santa Croce (1442-1478), both Renaissance architecture masterpieces by Brunelleschi. Their artist is Giuliano d’Arrigo aka Pesello, a skilled portrait and animal painter yet lacking astronomical knowledge. An expert must have guided him in the choice of the mysterious date, perhaps marking the arrival of the Count of Provence René of Anjou in Florence in 1442.

Other hypotheses exist. Perhaps July 4, 1422 celebrates the unification of the Western and Eastern Churches; or the beginning of a new crusade; or even a reference to the silk road, as the depicted sky is far from Florence – the way it is painted points to the view from the city of Shanhaiguan in China, where the Great Wall reaches the ocean.

Images and references travel in time and space. Today we speculate about those travels thanks to the iconological culture of the Renaissance and that of the so-called “dark ages.” Classical symbologies break. Interpretative incrustations melt. Depictions of the zodiac help these changes. As Ioan Petru Culianu writes in Eros and magic in the Renaissance, “a cultural era is not defined by the content of the ideas it conveys, but by the interpretative filter it proposes.”

Bibliography

- M. Battistini, “Astrologia, Magia, Alchimia”, Electa, Milano 2005

- I. Couliano, “Eros e Magia nel Rinascimento”, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino , 2020

- E. H. Gombrich, “Immagini simboliche. Studi sull’arte del Rinascimento”, Electa, Milano 2002

- A. Warburg, “La rinascita del Paganesimo Antico”, La Nuova Italia, Firenze 1966

- S.Zuffi, “Il Quattrocento, Electa”, Milano 2004

March 29, 2021