Death helps life in the anatomical theatre

Anatomical theatres were the literal and metaphorical houses of anthropocentrism. Are they resuscitating today?

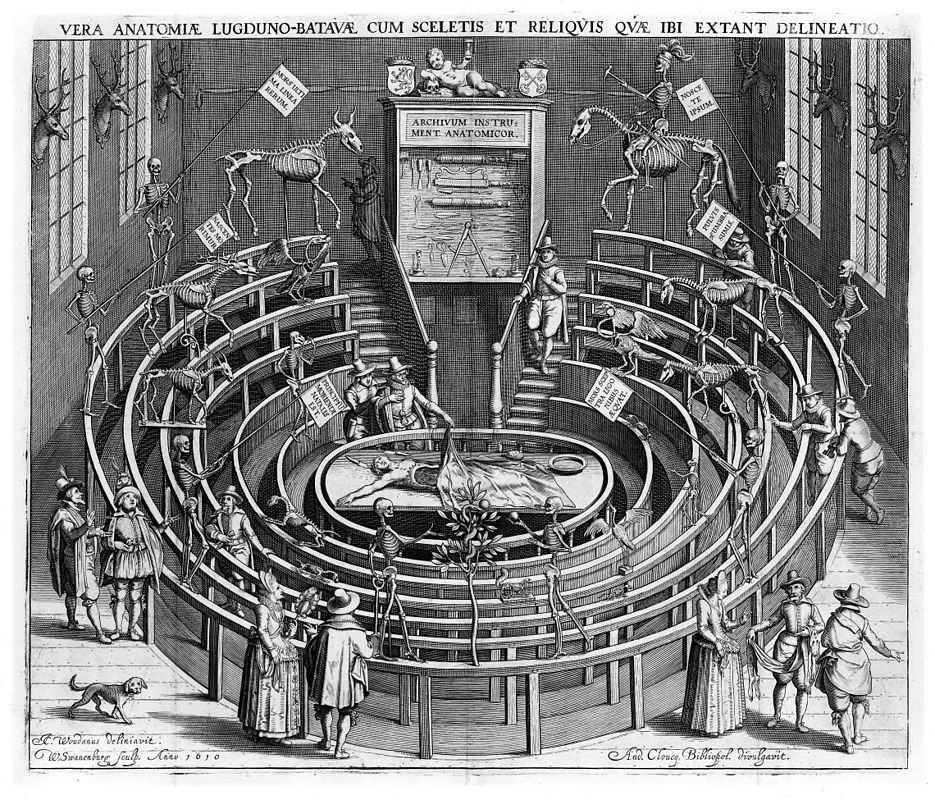

In 1715 London, William Hogarth produced a cycle of engravings entitled The Four Stages of Cruelty, which had the hidden purpose of moralising a society where cruelty towards animals and humans was common. The last engraving in Hogarth’s series is entitled The reward of Cruelty and it shows a bloody and splattering autopsy scene in the presence of the President of the Royal College of Physicians. It is set in an anatomical theatre. The President of the Surgeons, who never gets his hands dirty with corpses, points to the dead man’s organs with a long cane from afar. Doctors dissect on the table, pulling out guts and blood while a dog devours the murderer’s intestine. Beside, the bones are boiled in a witch-like cauldron. The building for the bloody dissection has an amphitheatre structure with the anatomical table on stage, surrounded by benches arranged in rows for the public, which is not only made of students. Places of honour are reserved for the highest government officials, the nobility and, as one climbs up the rows of benches, a whole audience of curious onlookers who have paid an entrance fee to attend an event: death makes itself beautiful.

Hogarth’s scene is a satirical version of an autopsy. These shows were generally organised in the cold season for health reasons, coinciding with carnivals as part of the entertainment of masquerade balls, a feast well described by Edgar Allan Poe in his novels. In reality, anatomical theatres, which existed as early as the 16th century, were innovative institutions, both scientifically and architecturally. To understand their origin, we need to go back even earlier, when the Bolognese anatomist Mondino de’ Liuzzi introduced the practice of autopsy in the curriculum of medical studies in the 14th century. Human dissection became a fundamental chapter in the history of science during humanism, with figures such as Leonardo and Andrea Vesalio as protagonists. The dogmatic nature of medical knowledge, which did not study bodies directly and was only inspired by the ancient Aristotle, Galen and Hippocrates was called into question. It was only with the rise of the autopsy, which etymologically means ‘to see with one’s own eyes,’ that the handed-down iconography of the human body began to be dismantled. Observation became crucial and progress could take place in a designated place: the anatomical theatre.

In his 1502 treatise Historia Corporis Humani Sive Anatomice, Alessandro Benedetti (1450-1512), a well erudite humanist practising as a doctor in Venice first described an ephemeral anatomical theatre, which can be dismantled after use. “A large space is needed,” says Benedetti “which must be very well ventilated, and within which a temporary theatre must be erected, with seats arranged in a circle. The space must be large enough to contain the spectators and to prevent the crowd from disturbing the surgeons performing the dissections.” With the second half of the 16th century, progress in the field of anatomy gave rise to the creation of permanent theatres. The first permanent construction dates back to 1594, commissioned in Padua by the anatomist Girolamo Fabrici d’Acquapendente and probably based on the ideas of the humanist Paolo Sarpi. It was used until 1872. A inscription in Latin in the entrance reads: “This is the place where death is pleased to help life.” The experience of dissection became a component of philosophical and religious education throughout the modern age: by learning about the perfection of the human machine, it was possible to contemplate the greatness of God and Nature but with man at the center.

The anatomical theatre was the metaphorical and literal house of anthropocentrism. It is from this perspective that Rembrandt, in his Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp from 1632, had the protagonist of the painting make the first autopsy cut from the forearm of the corpse. According to the canons of public dissections, the abdomen was the starting point, followed by the thorax, throat and skull. Only at the end the limbs were involved. Dr Nicolaes Tulp, president of the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons and Anatomists and the Vesalius of his time, considered the hand as the main instrument of medical work and thus to be the closest witness to the presence of God in the body. As in the birth of Adam in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, it is directly the hand of God that gives the masterly input to that of the surgeon.

Many historians have assumed that the architectural structure behind Dr Tulp and his team of members of the Surgeon Guild was that of the Waag’s Anatomical Theatre in Amsterdam. In reality, this was built in 1691 and Rembrandt, who died in 1669, certainly had not seen it. The architecture, known only through Rembrandt’s painting, probably refers to the deconsecrated church of St Margaret, which at the time was used partly as an additional venue for the nearby meat market and partly to house the college of doctors where autopsies were performed: an unexpected combination of butchery and surgery. The later Theatrum Anatomicum was modelled on the one in Padua, like many other European anatomical theatres that were built from in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: Groningen (1654/5), Copenhagen (1640/3), Uppsala (1662), Berlin (1720).

What remains today of the Waag’s Anatomical Theatre in Amsterdam is the empty space of the stage and the beautiful dome, from which the necessary light entered for the examinations. The structure was commissioned by the anatomist and zoologist Frederik Ruysch, whose coat of arms is the heraldic centrepiece of the dome. Discoverer of a new system of mummification, the scientist is the protagonist of the Dialogue of Frederik Ruysch and his Mummies, a poem in which the popular Italian poet Leopardi imagines the desiccated bodies of the mummies awaken and discussing the mysteries of death with the great anatomist, only to abandon themselves again to eternal sleep at the end. It is the same Great Sleep to which even anatomical theatres seemed condemned, having been rendered obsolete by the evolution of medical science. “Unfortunately, these little jewels of medical history, religion, economics, architecture and art have been neglected for a long time, often put to other uses or destroyed. Many have been fortunately saved, precisely because, like certain corpses, they have been forgotten in cold storage.” says Chiara Ianeselli, an art historian and independent curator who is part of the THESA project (Theatre Science Anatomy): an interdisciplinary study group on anatomical theatres founded in 2016, aiming at the promotion of their role in the history of medicine and art. Mapping and census are essential to document, enhance and preserve these places.

Only a few of the most important Italian anatomical theatres have survived, such as those of Padua, Bologna, Ferrara and Pavia. Others are currently receiving a great deal of attention, with restorations and rediscoveries, such as those in Modena, Pistoia and Lucca. Still others have disappeared, leaving rare documents to testify to their existence, such as the 1783 Covoni Girolami theatre in Florence. Between the 16th and 17th centuries, two Italian architectural prototypes led to the construction of all the other anatomical theatres in Italy and Europe: the Padua and Bologna models. In a research paper, THESA scholar Chiara Mascardi specifies how both these models were wooden constructions incorporated in a tall building of the University in Padua and the Archiginnasio in Bologna, but with different architectural characteristics.

The funnel-shaped skeleton of the theatre in Padua reminds of the inner structure of the ear. The sense of hearing is precisely what led to the design of a structure, which was also based on the model of the Roman amphitheatre. The architecture would reiterate that anatomy lessons were inspired by the stage reading of books, the source of dogmatic truths about the human body. The severity of this theatre, with the absence of decorations, gives importance to anatomical analysis in a space that exalts science and vision. Six rows of galleries protected by carved wooden parapets descend concentrically and steeply around the stage. The theatre can host about 200 visitors, without seating. At the bottom of the pit is the dissection table. The professor’s chair almost touches the table; there is little room for the assistants and the eight students holding candles, the only source of illumination. It was not until the end of the 17th century that the skylight was opened to provide the natural light necessary for anatomical observation. The conception of this austere room owes to the Belgian Andries van Wesel (1514-1564), italianised as Andrea Vesalio, a professor in Padua, founder of the school of modern dissectors, and author of De Humani Corporis Fabrica: a revolutionary book for anatomy published in 1543.

In Bologna, the anatomical theatre built in 1637 is completely opposite to that in Padua. Seats of honour are reserved for the cardinal legate and the highest government officials. “The anatomical theatres of Bologna and Padua are two examples of the way in which anatomy is understood”, writes Chiara Mascardi. “On the one hand, Bologna and its Mondinian structure (from Mondino de Liuzzi) would maintain the clear contrast between the Reader who gives commands ex cathedra and the dissectors, always creating a bifocal space with two centres of attention. On the other hand, in Padua, the work of Vesalio will affirm the importance of the proximity between lecturer and cadaver, and the need for the anatomist to practice directly, creating a monofocal centre of attention.” Designed in 1637 for anatomical lectures by the Bolognese architect Antonio Paolucci known as Levanti, a pupil of the Carracci brothers, the Bolognese anatomical theatre is a wooden amphitheatre decorated with two tiers of seats and statues: at the bottom, twelve famous doctors, including Hippocrates, Galen and Mondino de Liuzzi; at the top are the busts of 20 famous anatomists from the Bolognese Studio. The reader’s chair is flanked by two wooden statues known as the Spellati, sculpted in 1734 from a design by Ercole Lelli, a famous ceroplast from the Institute of Sciences known for his series of Scorticati. The “peeling” or “flaying” does not cause suffering in these bodies, which on the contrary are perfect and show splendid athletic musculature. Anatomy therefore goes hand in hand with art because it is considered a spectacle of bodily beauty. Above the canopy is a female figure, the allegory of Anatomy herself receiving a gift from a winged putto: not a flower but a femur.

The idea of anatomical dissections as an entertainment spectacle led the London Barber and Surgeon guild to build an anatomical theatre in 1636. Architect Inigo Jones was called for this job following his famous constructions of theater buildings. Jones knew Padua and especially the anatomical theatre of Leyden. The drawings of his project found in Worcester College echo these models with some more popular aspects. Scenically, the central arena is modelled with spaces similar to those of the Cockpit-in-Court, also known as the Royal Cockpit, one of the first sixteenth-century theatres in London, located in Whitehall Palace where Henry VIII enjoyed watching cockfights. The oratorical precept docere et delectare was respected: on the one hand anatomical discipline, on the other hand divertissement. The real spectacle was in the form of slaughtering, blood and guts. The walls were adorned with portraits of English kings, including Charles I who was beheaded in 1649: a veritable case of royal dissection.

Back to THESA and following the path that links Italian and European anatomical theatres, the organization’s scholars do not limit themselves to mapping but they also propose a project that could be defined as resuscitation. Says Chiara Ianeselli: “We organised a series of contemporary art exhibitions grouped under the title Les Gares, where various artists are asked to carry out a site-specific project within the anatomical theatres.” In this context, numerous artists have already presented their works in the anatomical theatres of Amsterdam, Bologna, Modena and Padua, in a very modern auscultation of the revealing heart of the ancient septic practice. Molière joked about it in his The Imaginary Invalid:

T. Dia. (again bowing to Angélique). With the permission of this gentleman, I invite you to come one of these days to amuse yourself by assisting at the dissection of a woman upon whose body I am to give lectures.

Toi. The treat will be most welcome. There are some who give the pleasure of seeing a play to their lady-love; but a dissection is much more gallant.

June 1, 2021