Every ticket wins: hyperpositivity in the work of Elif Saydam

Elif Saydam’s references are literal but overstimulating. The overflow of information makes you at times dizzy—and tired

When life gives you lemons, make lemonade. Printed on mugs, in calendars or as wallpaper, today’s social mantra reminds us that your success depends on what you make of it. And that you can make it! Yes, we can. It is based on the assumption that the search for happiness is the highest goal in life. In The Burnout Society, Byung-Chul Han describes the exhaustion that comes from staying positive. The excess of positivity in our achievement society suggests that everything is possible and ultimately leads to self-exploitation. Working too hard and not working hard enough.

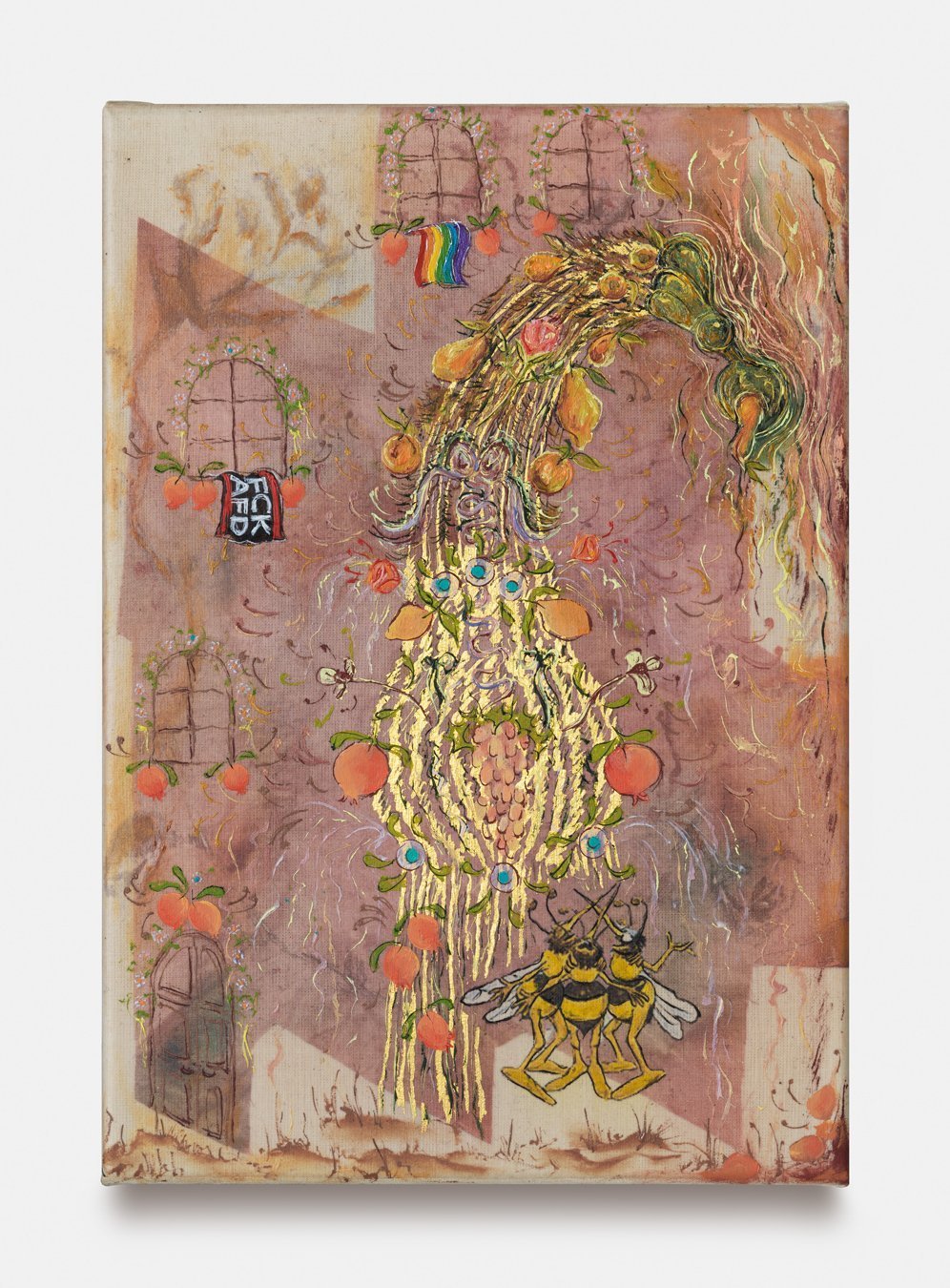

In Elif Saydam’s works lucky stars are grinning at us everywhere, a somewhat deranged smile. Their red eyeballs reveal their burnout and their high. They can be found on their paintings, installations, and carpets next to fruits, flowers, ottoman patterns, and other decorative elements from mass culture that put categories of taste to the test. Not without humor but with a serious interest in questioning to what extent kitsch has had a justification in art since the separation between low and high culture. Saydam uses decorative elements in an overbored abundance. With this opulence, the artist locates themselves in the camp and the queer:

Camp beauty is beauty rescued from its idealist ideology. It is a beauty whose dignity arises out of its constitutive rejection of all attempts to normalize it to idealist standards. Any idea of beauty conceived without this rejection, by contrast, would be tainted by the misery of capitalist exploitation, the violence of idealist sovereignty, or fascism (or by all of these at once). [1]

And still, Juliane Rebentisch states further in her essay about camp materialism: Even for Jack Smith, pioneer of camp, beauty “is not projected into the realm beyond the commodity fetish. Rather, beauty is, as it were, found in the fetish’s decrepitude.” [2]

Saydam’s references are literal but overstimulating. The overflow of information makes you at times dizzy – and tired. Like the permanent feel good mentality of advertising. How much is too much? Hyperdecoration leads to hyperactivity: “Excessive positivity also expresses itself as an excess of stimuli, information, and impulses. It radically changes the structure and economy of attention. Perception becomes fragmented and scattered.” [3] Located at the Harburger Bahnhof, a former arcade and a waiting room with a history of royal class society, Saydam’s latest show …schläft sich durch refers to the aesthetics of the casino. A printed carpet (Blue Saloon, 2021) literally evokes the soundscape of gambling machines. It is joint by their small format paintings with the recurring motif from a 16th-century Ottoman miniature, a golden fruit tower, similar to a rich cornucopia from Greek mythology, signifying opulence and prosperity. “For many years I’ve been gilding works in the ways of the old masters. It started as a kind of joke. But there was something in that gesture that packs a punch for me still”, Saydam describes their interest in pageantry.

Their large sculptur-ish paintings hanging from the ceiling and stretched (bluntly crucified) on industrial metal grids (The Outlier; The Producer; The Drone; The Landlord, all 2021) seem no less sacred. Saydam makes use of worn clothes that they sew, quilt, paint, dye, and decorate. It is a practice that they have been following up on for the past years. The metal constructions in combination with clothing invoke associations to physical labor like mining as well as commodity and sexual fetish.

Glückspilz, Glückslos, Glücksklee, and other lucky charms like the evil eye (nazar boncuğu) promise the fast track to happiness and security. What all those lucky symbols have in common is a certain kind of naïve comic language. The artist is interested in the usage of cartoon aesthetics in mass media that causes the infantilization of consumers: Cuteness as innocent but not less manipulative seduction. By appropriating and repeating symbols they become icons which ultimately gives them value. When juxtaposing more explicit messages (FCK AFD) flagged out of a Kreuzberg window with rather obscure ones (RAID Insecticide cartoon characters) as in Artists (Gossip) (2020), they do this with such casualness that you might think they all emerged from this one imagery. Maybe this is – in relation to Jack Smith’ beauty – the commodity fetish’s decrepitude.

After a year of pandemic, society is in the state of grosse fatigue. Stay positive and test negative became the new mantra of our time. Even in times of crisis there is no space for exhaustion. Rather the pressure to perform is increased and social injustices are reinforced. Don’t let yourself down, the lemons wink at us, the roses flirt with us.

Roses are red, Violets are blue, Sugar is sweet, And so are you.

[1] Juliane Rebentisch, Camp Materialism, Cologne/Berlin 2020, p. 16.

[2] Ibid., p. 17.

[3] Byung-Chul Han, The Burnout Society, Stanford 2015, p. 12.

June 14, 2021