Symbol by symbol, dust piles up

Read about artists’ obsession with dust, from enigmatic depictions in 16th and 17th century painting to post-war imagery and symbols

Memento, homo, quia pulvis es, et in pulverem reverteris (Remember, man, that dust thou art, and unto dust thou shalt return). God’s outburst against Adam and Eve at the moment of their expulsion from Paradise, guilty of biting the apple of knowledge, is a cry of condemnation: total disintegration of the human body after the labours of life. We are all reduced to piles of scattering dust. There might not be a better image to give a sense of abandonment, dirtiness and disappearing existence. Above the earthly dust there lies paradise, the essence of cleanness, where there is no need for a broom and elbow grease to remove dirt and everything is divinely tidy.

“In the 15th century, artists were among the keenest observers. They devised systems to better observe and represent the world […] in works of art. Life was depicted entirely free of dust.” writes John A. Amato in his book Dust: A History of the Small and the Invisible. “Artists idealised a nature free of dust and dirt.” Amato associates dust with two-dimensionality and the clean image with three-dimensionality, which promoted the birth of perspective. How can one think of Piero della Francesca’s Madonnas if not in a divine, transparent perspective space, absolutely devoid of the dirty, demonic and human dust?

Dust-free Paradises

It is easy to think of a metaphysical vacuum cleaner that magically cleans everything in the divine world, though in the human world dust must be dealt with. Perhaps it is precisely this desire for cleanness, which for a moment elevates the domestic space of a house to the likeness of a small Eden, that explains the presence of so many brooms, mops, scrubbing and sweeping tools in Dutch 17th century paintings. These deceptively innocuous representations of everyday life, where the mop and broom are often the protagonists, constitute a true niche even within the world of Dutch genre painting, which developed in the mid 17th century at the height of the economic power of the Low Countries. Members of the Dutch elite, proud of their social status, demanded art that reflected their rising wealth.

A new wave of genre painting saw the light of day at the beginning of the 1650s: artists began to concentrate on scenes of private life in elegant interiors, with women and cabinets, flowering maidens with pearly earrings, gentlemen and lacemakers. But why, if this kind of painting was supposed to be a hymn to the prodigious Calvinist industriousness of a new bourgeoisie, are the “non-places” of dwellings the protagonists? There was an interest in the empty corridors, the foreshortened passages between rooms, in which one could glimpse into people’s business happening inside. In the foreground, on the other hand, were the courtyards, the walls, like those of Delft painted by Vermeer, who pictured with realism what is only apparently banal.

Dutch Dust

Brooms, mops, buckets and dusters, almost absent-mindedly forgotten, stand in the foreground. They are works of silent power, to borrow an expression used for Delacroix’s paintings. In the works of Pieter Janssens Elinga (1623 – 1682), a lady playing the virginal and a cleaner sweeping carefully exist in the same room. A world of women, certainly from different social classes, where one leads and the other follows, where the common aim is completing the household chores; a small, ancient world, a way of evoking the moral and spiritual purity represented by domestic cleanliness, with sweeping light coming in through the clean windows to create a game of chess.

Seventeenth-century Dutch artists mastered acute and faithful realism, but also the great tricks of perspective to simultaneously describe and deceive. The works of Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627 – 1678) are a powerful stimulus of pictorial invention that confronts viewers with representative enigmas. His perspective box is the best example of the artist’s meta-pictorial skills, probably stimulated by his contact with Carel Fabritius when the two painters were both Rembrandt’s students in Amsterdam. This perspective box shows a “filmic” sequence of interiors conspicuously devoid of protagonist-figures, mysterious thresholds, forking paths that open onto the disturbing black and white chequered tiles of the floors; sometimes an astonished domestic animal appears, a dog, a cat, but it is the accessories – chairs, slippers, mirrors, pictures, keys and among them the broom, strategically placed – that evoke a story.

Dust and Gadgets

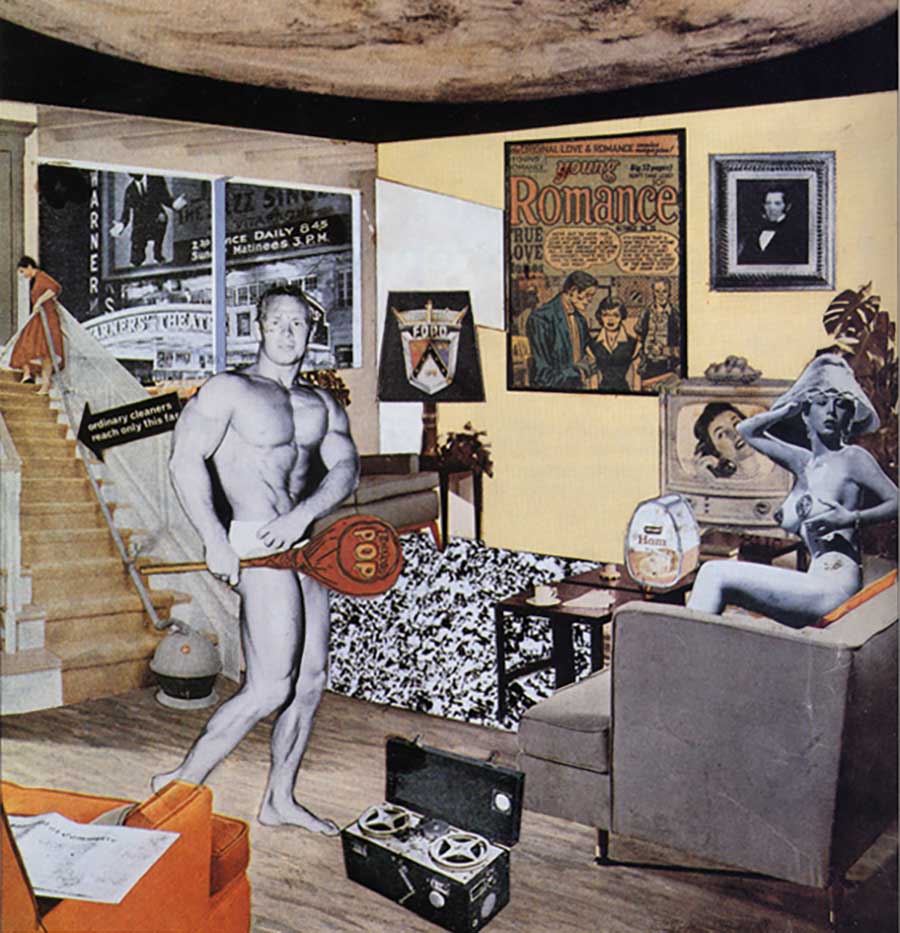

Forget about Marinetti’s rant “War, the world’s only hygiene.” At the height of the post WWII economic boom, it was the hoover that became the symbol of the great pop industry of cleanliness. The hoover is a new weapon to eradicate dust. Picking up the machine’s hose was a revolutionary act, as in Richard Hamilton’s 1956 collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? In 1990, Hamilton, the father of UK pop-art, said of his collage: “The point was to put into the cramped space of a living room a representation of all the objects and ideas crowding into our post-war consciousness: my ‘house’ would be incomplete without its symbolic life force, so Adam and Eve posed with the rest of the gadgets.”

What happened to the biblical condemnation of Adam and Eve, pulvis es, you are dust… Everything has been modernised, but the obsession with dust has remained, even if in the years of consumerism the archangel Michael has been reduced to the servant of the Edenic couple, and his sword is the great suction pipe with earthly mechanics to clean and tidy the house, maintaining a due and proper distance from the two biblical protagonists who amuse themselves with a gigantic and turgid lollipop, an Adam’s apple celebrating the new junk food while the beautiful Eve poses as a Pin Up.

Dust and Monuments

The hoover performance later improves. The big machine rises to the metaphysics of suction. The artist’s hand disappears and the machine that vigorously swipes carpets and floors becomes self-documentalised in the transparent boxes of Jeff Koons. From 1980 until 1987 Koons made a series of sculptures titled The New consisting of vacuum cleaners displayed in plexiglas cases. Koons’ creativity is passive and vacuum cleaners are the objects of our desire. Shimmering seductively under the glow of fluorescent lights, they drip with fascination. They are suspended in a state of absolute perfection. Koons commented: “In my series of works The New, I was interested in representing a psychological state of the individual related to novelty and immortality: the overall figure, the Gestalt, came directly from an inanimate object, a hoover, placed in a state of immortality.”

Koons would go so far as to compare the shiny chrome plating of the hoover, which protects and traps dust, to large maternal wombs. This is a far cry from the ready-made object of Duchamp’s urinal or bottle rack. We are talking about hoover bodies virginally made in Heaven. This would be the title of a later series, when Koons collaborated with his partner Ilona Staller. Yet there is some porn in paradise too: the hoovers, guardian angels, have eliminated the sign of the dusty passage of earthly time.

[Here is Duchamp’s first person explanation of readymades. Ed.]

Fingers on Dust

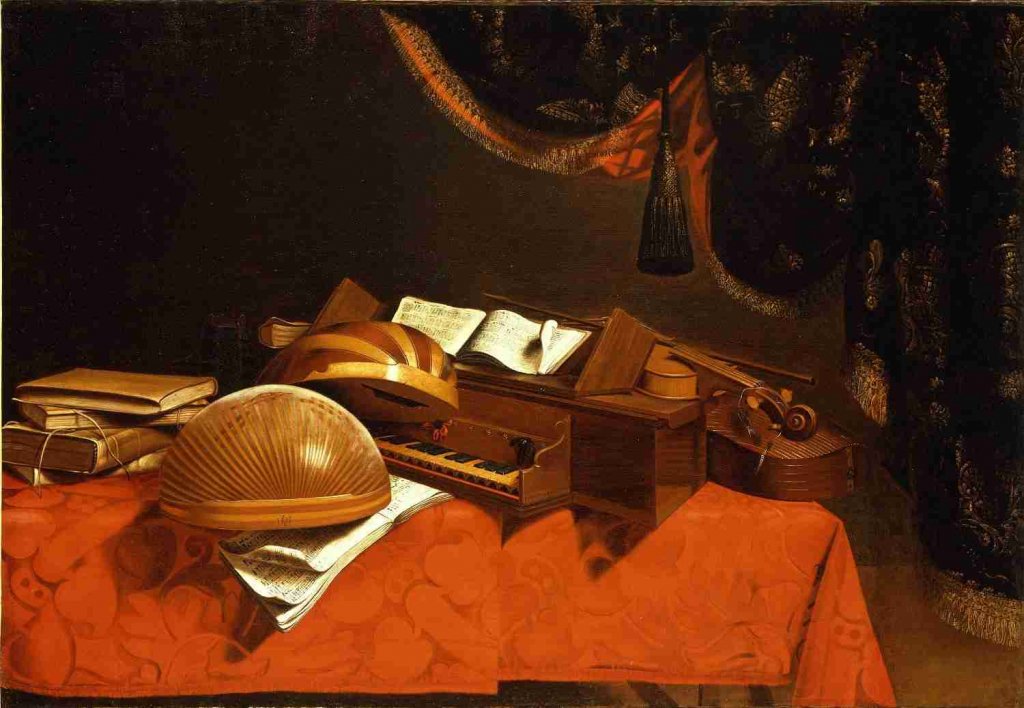

Sometimes cleaning is a strange way of leaving a mark. In the works of Evaristo Baschenis (1617 – 1677), a 17th century painter of still lifes, dust is a protagonist instead of a casual painterly exercise; it is the substance of his pictures. Piled up in full view on musical instruments, from lutes to mandolas, from guitars to violins, the dust is highlighted by the fingerprints rubbed on the objects, almost shrill sounds that raise trills of dust. Baschenis’ poetics are in harmony with the baroque verses of Giovambattista Marino: “The painter’s goal is wonder […] To those who don’t know amazement, pick up the comb!” His dusty instruments are a great piece of bravura, a powerful effect of illusionism with a further tour de force: the finger.

Throughout the 17th century, dust meant Vanitas, the imminent sense of the end that erases everything. Yet Baschenis’ dust raises doubts. Was he trying to demonstrate how painting, by analogy with music, is capable of the devil’s trills and knows how to make the impalpable diabolical dust visible and tactile – just as Paganini’s pinch makes a demonic sound audible? Can the Toccata (touch) of fingers and painted Fuga demonstrate the perfect conjunction of hearing and sensing through the image of dust?

To Photograph the Dust

Speaking of Marcel Duchamp, of whom he felt he was the heir, John Cage said: “The rest of them were artists. Duchamp collects dust.” Man Ray recorded the accumulation of dust with which Duchamp wanted to reproduce the different shades of color on his Le Grand Verre, The Great Glass that kept him busy from 1912 to 23 until he left it incomplete. Duchamp wrote some cryptic notes full of double meanings, speaking of the need for the “breeding of dust” (élevage de poussière) on glass: he didn’t want to complete the work with pigments, but changing it through dust for a new set of optical refractions.

Man Ray’s photos from 1920, exhibited in 2015 in Paris at the Le Bal Museum under the curation of Gerhard Richter (title: Dust / Histoires de poussière d’après Man Ray et Marcel Duchamp) show the development of Le Grand Verre through the piles of dust on it. The dirt participates in the work. Man Ray’s photographic cuts are low, distorted, almost anamorphic; the light has gone through the lens for hours to obtain these photographic renditions of an imaginary, lunar landscape, illuminated by non-colours, created for a non-painting: “Not in the sense of opposition to painting or to colour,” writes Elio Grazioli in his La polvere nell’arte, “but in the wholly Duchampian logic of difference, indeed of indifference, to create something other yet fruitful: the readymades on the surface of Le Grand Verre.”

How can a work of art in which dust is a key element be presented through photography? What are the criteria for rendering this second skin on film while safeguarding its symbolic integrity? The photographs of Luigi Ghirri collected in the volume L’atelier Morandi and those dedicated by Man Ray to Duchamp’s Le Grand Verre provide an answer. Ghirri creates an analogy through the fingerprints on dust captured in the studio of Giorgio Morandi, one of the most solitary artists of the 20th century, “a friar” as Cesare Garbali defines him in Falbalas: “Morandi, the man who hated everything that glittered; he’d let a layer of dust settle on his objects to dampen their brilliance.”

Thirty years after the death of Morandi, Ghirri entered his studios on Via Fondazza in Bologna and in Grizzana, honouring with a series of shots that same luminous discretion of the paintings; he imitated the immortal “lightless touch” emanated by bottles, jugs, kettles and pots “without the suspicion of obsession – this is Morandi’s miracle.” continues Garboli. Ghirri made these frozen interiors, yet warm thanks to the dust that covers them, dialogue with the dirty marks on the plywood panel behind them: they are Morandi’s fingerprints and touches of paintbrush, grey on grey, rubbed on that soft wood, bringing in the residues as necessary elements to understand the work. Ghirri captures very well this hinge between Morandi’s still lifes and his hard work of painting, of the dirt to be left under the doormat in order to arrive at that sense of archaism of the objects covered only with that much necessary dust.

Bibliography

- John A. Amato, Polvere. Una storia del piccolo e dell’invisibile, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino, 2002

- Elio Grazioli, La polvere nell’arte, Bruno Mondadori, Milano, 2004

- Celeste Brusati, The Universal Art of Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627-1678), Amsterdam University Press – Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wp6wc.6

- Cesare Garboli, Falbalas. Immagini del Novecento, Garzanti, Milano, 1990

- Dust / Histoires de poussière d’après Man Ray et Marcel Duchamp, Catalogo della mostra a cura di Gerhard Richter -Museo Le Bal-Parigi, 2015/2016

- Georges Didi-Huberman, Sculture d’ombra. Aria polvere impronte fantasmi, Electa, Milano, 2009

June 26, 2021