Justine Neuberger: coughing up a strand of angel hair

Preferring her goofier, odder doodles, Justine Neuberger develops her swirly figures. “And then there is what the paint wants to do.”

Looking at the paintings of Justine Neuberger, one gets absorbed in a thin vellum made of loosely threaded narratives. Upon asking her what words she thinks of while working, she smiles sideways and slowly says: “softness, curls, spirals, sinew, clouds, mountains.” Justine Neuberger grew up in New York in a traditional Jewish family in the 1990s. In Fiorello La Guardia High School, a public school with extra art classes, she learned the craft of oil painting. Later she obtained two Majors in art history and painting, after which she taught English to children, thinking that being an artist was just too dreamy. Her background pierces through her paintings: tale, kinship and intimacy meet in a complex contact zone.

“The production of the past remains tied to the contingencies of the present, and is limited by them.” [1] What we distinguish as being our “main stories,” Justine Neuberger compares to tentpoles, “and the narrative is the tent that falls over them.” She points out the difficulty of finding and defining what we later call the key moments or turning points.

The paintings are personal and symbolic, but loosely so. The characters and their interactions read like a signifying chain, rather than as a singular story. Different memories coagulate; fairy tales, folklore and judaism phantom and trigger historic memory. All elements speak to each other, through colours and what feels like invisible connections.

Somewhere

Justine Neuberger shares a passage from Trauma Explorations in Memory by Cathy Caruth, which reads:

Poems in this sense are always under way, they are making toward something.

Toward what? Toward something standing open, occupiable, perhaps toward a “thou” that can be addressed, an addressable reality.

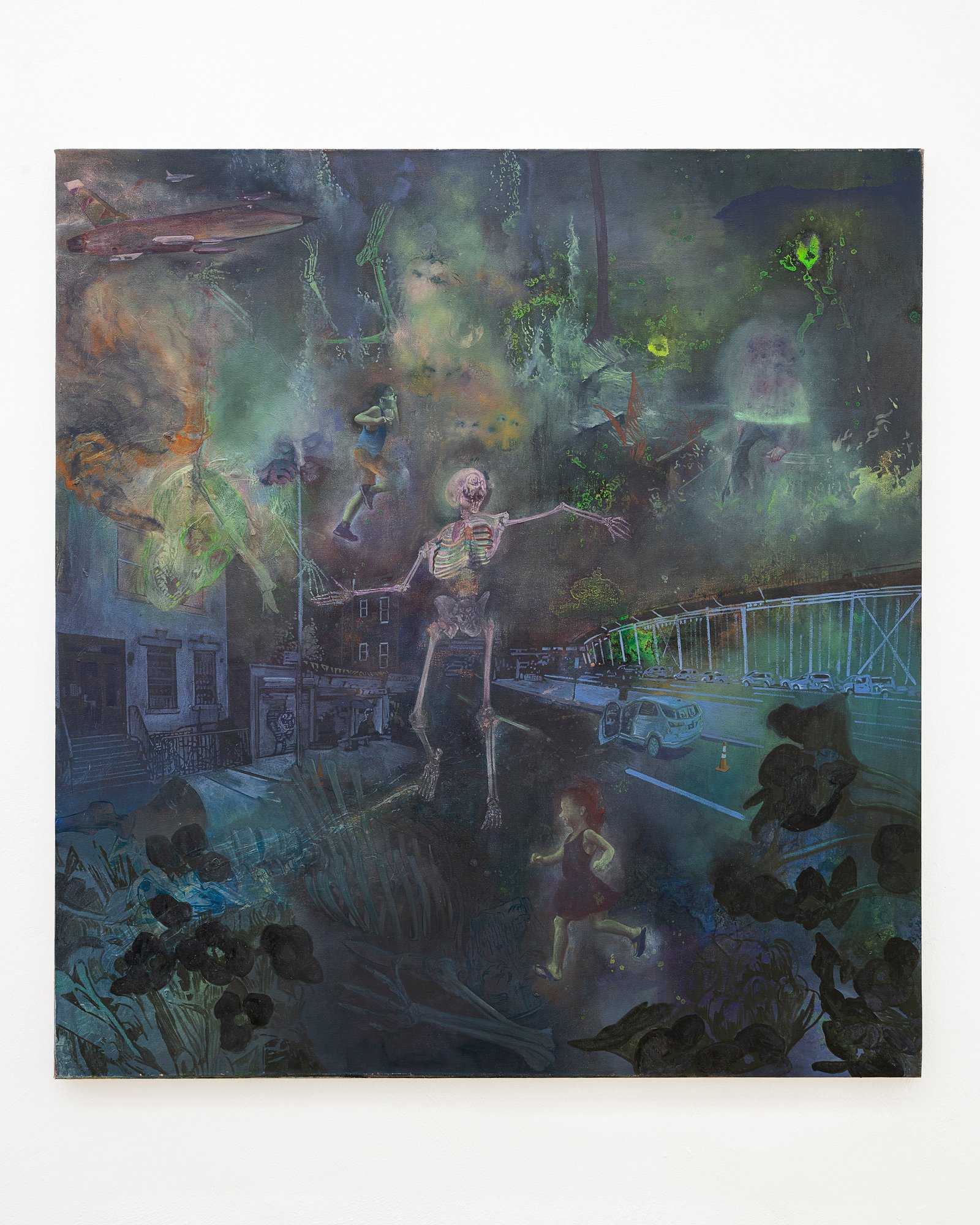

Leaning on a structure similar to the viewer’s, Neuberger’s fantasy world allows for virtue and desire to play out, with often the possibility for a lesson learned. “The monster,” she says, “is always something from our world; a darkness on the inside lurking.” Yet likewise, lifeguards and images of protection or rescue recur. “Painting is a language in itself, line, as colour are feelings in themselves. I try to marry figuration and ornament, details that are attractive to different types of viewers who don’t necessarily know the language,” she says.

Using different levels of finish in the painting, areas of haziness create a static place to dream from—beyond a fixed narrative, and similarly, between what she wants and what the paint wants: “How much is up to me, or up to the world?” Interested in the autonomy of watercolour, turpentine adds to the haze in her oil paintings.

Everything looks soft and fluffy in the way the paint meets, but there is a sharpness in the somewhat biting characters and the relation between naiveté and something more ambiguous, edging the demonised witch’s presence in a fairytale. It’s with the same curiosity of a child plunging into descriptive narratives that the paintings unfold, though nothing moves, you trace the moments before and after, eyes shifting back and forth somewhat hurriedly between everything that’s going on. The trees suddenly become more doomy as the grim shows itself; or does it?

Being taken in, on, away, the tableaux’s elements and the manner in which they are painted feel like little sucking fish nibbling at your eyes and cheeks. You hypnotizingly get abducted to a world without scale, in different senses of the word, like vapors, hanging in the in-between states that the paintings depict. The figurines have an opaqueness, a mysterious untouchability, and a palpable potential of turning; they are forever ambiguous and charged. A soft floor cover in blush pink in one of her exhibitions dims the steps and softens the approach to the mystical lands. There is seduction, through blankness or by an overdose of layered intentions. There is violence, all forces are pulling.

We seem to get an insight into a world that is not ours, but it once lived in our imagination, when bedtime stories and their soft pencil colored illustrations made our eyes roll inward. The visual language is captivating, absorbing, sucking, grabbing us with too tiny fingers and dirty minuscule gripping fingernails. A bloody sky on Halloween night, a disproportionate halo-like woman; there is a secrecy, a magical spin. The endearing closeness of recognition brings back a child’s fright too, the doomed lessons of life that all stories seemed to be thriving on.

When Justine Neuberger was combining painting with a day job, she used to work on one painting at a time, maximising. Now, fully devoting her time to painting for the past two years, she has been working in little series, spreading out the material over a group of five canvasses, rather than developing everything within one frame. Either way, her narratives move forward over time. During the process of painting, relations clarify and change, from the original idea to a composition of gestures and poses, and a style taken from the goofier doodles in her sketchbook.

There is the Ghost of Words in Other Words

Starting from a set idea of what she wants to convey, Justine Neuberger puzzles together backgrounds, gestures and facial expressions that suit the purpose. Preferring her goofier, odder doodles, she leans on those to develop her swirly figures. “And then, there is what the paint wants to do.”

[On the relationship between figurative painters and their figures, here is the take of Giangiacomo Rossetti. Ed.]

“There aren’t many hard edges in nature.” she says. “Being outside, I wonder how light will fall in my world?” Neuberger uses smoke to paint; (that little smile again) “curvy, curly soft and badass.” There seems to be angel hair everywhere.

[1] London Review of Books, “Stick-at-it-iveness”, Mary Hannity, on Imperial Intimacies: A tale of Two Islands by Hazel V. Carby

December 22, 2023