The artistic fate of the wind

Over the centuries, the wind has always been an iconographic presence for artists, touching upon fate, religion, chaos, love, and nature

Gust of winds hit strongly in the words of Hesiod: “Lenaion—the entire month—is rife / With evils, each day like a skinning knife / Avoid it, and the killing frosts brought forth / On the earth when the wind blows from the North / Through Thrace, mother of horses, and sets seething / The wide sea. World and wood howl with its breathing. / Falling on crowds of lofty oaks and dense / Groves of fir, in the mountain dales, it bends / Them down to the rich earth; the whole wood wails.”

Artists have dealt with the wind for millennia, from Ancient Greek to Mantua in the 16th century, to Parisian paintings of the Belle Époque and beyond. They have delved into the symbolic value of this natural phenomenon, between fate, stars, destiny and the power of chaos.

Wind Changes Destiny

In Mantua, the Camera dei Venti (Room of the Winds) at Palazzo Te was designed between 1527-28 by Giulio Romano. Niccolò da Milano was the probable creator of the stuccoes. The room takes its name from the personified faces of the winds in the lower part of the vault: swollen cheeks blow, puffing at full force. It turns out there is a strong connection with the zodiac in these artworks. The influence of the stars on the destiny of humans is reflected in the inscription by Juvenal on the door of the south wall: “Distat Enim Qvae Sydera Te Excipiant” (It all depends which stars receive you [when you are born]). The iconological program of the Chamber is based on ancient astrology and astronomy texts that enjoyed the highest authority in the humanistic circles of the time, such as Manilio’s Astronomica and Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura. However, the winds of Palazzo Te seem to disrupt destinies and the predestination commanded by the stars, as a gust of wind is enough to change fate.

In the Sala dei Giganti (Room of the Giants), also at Palazzo Te, the cataclysms produced by whirlwinds and hurricanes overwhelm the bearded giant, who is distracted while he plans the reconstruction of the cosmos along with Jupiter and the eternal gods – an evident metaphor of enlightened Gonzaga’s power. Giulio Romano’s art is a real power and no longer aims at illusionistic representation – the artist creates catastrophes as only God could. Even the architectural limits of the room are overcome, as he smooths corners and walls, creating powerful painterly effects. The floor too, built with river pebbles, seems to enter the painting, creating a vortex of instability and restlessness. Here everything is gigantic. Those who enter seem helpless in the eye of a storm. Writes Giorgio Vasari in the Lives that “no artist could conceive anything more terrifying and […] whoever enters that room and sees the windows, doors, and other such like things all awry and, as it were, on the point of falling, and the mountains and buildings hurtling down, cannot but fear that everything will fall upon him, and, above all, as he sees the Gods in the Heaven rushing, some here, some there, and all in flight…”

Miniaturized Wind

Nevermind the gigantic scale: the wind maintains its power even in miniature books. Representations of the winds can be found in the miniatures of the 15th century Italian Books of Hours, even with a fairly obsolete iconography. The young double horn player in the illustration is Marcius Cornator, a figure linked to the month of March, half human and half demonic in nature, with a short robe and scruffy hair. Marcius Cornator was close to Mars, to which the month of March was dedicated. The horn and the uncombed hair become an allusion to the winds that characterize the month of March. Marcius Cornator becomes a herald of the spring season and its winds.

Dazzling enamel colors and a powerful athlete’s body: this is Aeolus, a blue God in the miniature of the Antiphonary by Liberale da Verona. He is painted dazzlingly and strongly – a small late 15th century monument in the space of a coin. Aeolus does not need oars to ride the ark on which his running foot rests; his lungs and peacock-wheel hair are enough for him. He catches the breeze at his stern while a long chlamys rolls up in the shape of a whirlwind. These wind eddies formed by the god remind of Van Gogh’s Starry Night, where nothing is calm and peaceful. All is restless and the air seems to swallow us.

The Wind of Envy

In one of the episodes of the Odyssey, Ulysses lands on the island of Aeolia after escaping from Polyphemus and his annoying habit of dining with human flesh. Aeolus, god of the winds and king of the island, offers hospitality to fugitives. On the last day of their stay, moved by the tales of Ulysses, he gives him a wineskin containing all the winds adverse to navigation to Ithaca and orders him never to open it. Only the gentle Zephyr would blow and push the ship towards Ulysses’ homeland. But, as we know, “slander as a breeze is” (as Don Basilio sings in Rossini’s Barber of Seville): the companions of Ulysses, envious of that gift given to him by Aeolus, uncork the bottle of winds as they believe it contains a treasure. The winds explode, causing all of Ulysses’ ships to wreck except his.

Isaac Moillon, painter of Louis XIV, depicts his king as Aeolus giving the bottle of winds to Ulysses. The wind is there, moving the king’s cloak, the hair of Ulysses and his companions behind. The lower part of the work might make you feel dizzy. In the foreground is the departing ship in an oblique and soaring position, complete with a sweet and mephitic siren as a figurehead. Everything moves in the harbinger of the horrific future whirlpool.

In the Royal Park of the Reggia di Caserta, small caves are hidden between the jets of a veil cascade that descends into the riverbed like an exedra of an immense fountain. These caves are the houses of the winds in the metaphorical kingdom of Aeolus, the protagonist of an episode of the Aeneid in which Juno asks the stormy intervention of the god of the winds to prohibit Aeneas from landing on the shores of Italy. The call is useless, of course. The refugee Aeneas will disembark, the future Rome awaits him. Perhaps this is why the grandiose fountain designed by Vanvitelli in the mid-1700s and never finished (54 sculptures planned, of which only 28 realized) is missing the images of Aeolus and Juno, the opponents of Aeneas.

Four sculptures of Zephyr exist however. He is the gentle wind with delicate wings. His seductive grace is typical of late Rococo. Certainly the most iconic Zephyr is the one embraced by Aura while a breeze of flowers blows to gently push the shell across the water where the goddess of Love resides – the enchanted Venus sails like she was on a windsurf. Ethereal, sensual, the pair of gentle winds fly softly, quoting Botticelli and his famous venus, a Hellenistic gem owned by Lorenzo the Magnificent. The wind of classicism blows and shapes the Renaissance.

Wind-blowing God

What happens to the representations of the wind when it encounters Judeo-Christian theological questions? The wind becomes the symbol for the godly ineffable. Animus in Latin comes from the Greek ἄνεμος, that is, breath, wind, principle of life. In the Bible, it is God who awakens Adam to life with the vital breath and the wind represents divine action not only on humans but on the very origin of the universe. God gives a succession of efficient commands. The divine will grows, takes strength, swells in typhoons and tornadoes to divide land, water, and skies.

The wind also blows in the Sistine Chapel. In a grandiose slow motion effect, Michelangelo generates successive “frames” of the birth of the universe amidst harsh skies. Spreading his arms vigorously, the Almighty points his index finger and the sun comes out of the dark. But the Almighty is in a hurry and moves away to proceed with the creation of other worlds and new galaxies. The days are few to complete the feat and a wind of action animates him, so strong that his iridescent pink robe rises and God is forced to hold it back while his backsides appear uncovered.

The Ancient of Days by William Blake is an etching originally published as the title page of Europe a Prophecy in 1794. It is the representation of the Architect God or Urizen, a term coined by Blake himself. The figure is squatting, naked, holding a difficult pose with a totally bent leg; it is as though the body exerted effort from a wind tunnel. He stretches his arm down, the Almighty, where darkness and emptiness reign. His face looks down as a strong wind blows across his long hair and beard. The body is shaken by the frightening pneuma of creation, bringing order to the nebulous chaos of the universe: only he can square the circle.

On the wave of creative inspiration, even the Father of heaven and earth created by Tintoretto between 1550 and 1553 is seized with such dynamic vigor while he breathes life into the world. Wrapped in the divine aura, God looks like a sprinter who takes the push from a tree as a starting block for his Creation. Tintoretto’s “photographic” cut of this divine figure is innovative.

The wind of Belle Epoque

Certainly it is an abrupt transition to go from the winds of metaphysics to decadent ones, like those shamelessly blowing the Parisian boulevards of the Belle Époque. What a frisson the wind of Paris gives to the mademoiselles as they stroll along the Seine. The French Jean Béraud was a master of cheekily portraying Parisian girls. He depicted them as soon as they bent down, taking shelter behind an umbrella for example. Their bodies flex slightly, pushing up their butt, which is already accentuated by the whalebone half cage of the skirt or the padded dress (very aptly called “Cul de Paris”). The rogue wind slips through the folds of the skirt and reveals the crinolines of the linen covering the sword-shaped ankle. Acuity and irony guide the brush of Béraud, who was also the witness of Proust’s duel against Jean Lorrain in 1897 after an insulting article in Les Plaisirs et les Jours.

Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow!

(Shakespeare – King Lear)

19th century wind

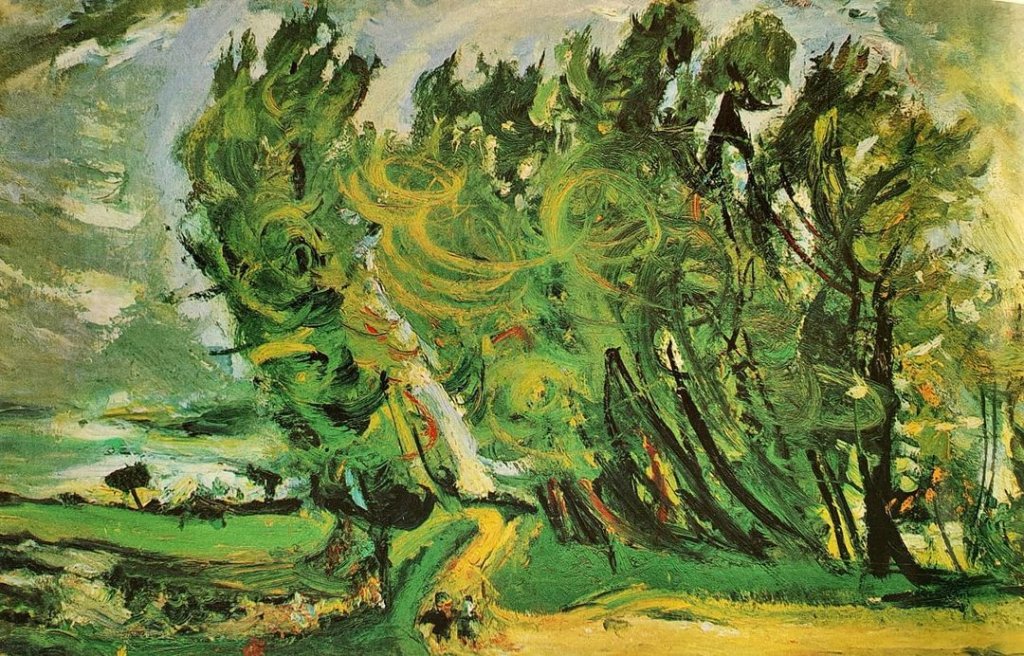

Millet with his Gust of Wind from 1873; Monet with his Wind Effect (Series of Poplars) from 1891; Fattori with his Libecciata from 1895; and then Vallotton with Wind from 1910 and Chaime Soutine A windy day in Auxerre in 1939: this is nature swept by the wind without much of a hidden meaning. The Millet tree, made with dense brushstrokes, resists, still clinging before being uprooted like the heroic protagonist of a grandiose history of nature. Monet poplars seem to be saying that reality is truer if painted with a bit of randomness, so no easel and no pose, as Monet paints sitting on a boat in the Limetz swamp on the left bank of the Epte north of Giverny.

Horizontality is the measure chosen by Fattori in his Libecciata. It is the line of the Tuscan seafront. A tripartite division into horizontal bands of color accentuates this sense of length on which the wind runs. Quick strokes of almost solidified white lead make the foam on the dark crests of the billows. In the center is the large folded dark spot of the tamarisk, shaken by the gusts of wind and alternating with the clear clays and the dry green of the earth. Behind, the gray-blue and golden liquid shades sweep into the sky. There is no drawing as all needs to feel natural: the effects of the wind are created by the unsettling light effects from the gradient of the shadows.

The bent and mobile trunks of reeds in the Wind by Felix Valloton shows the artist’s Japanese influences. The warm brown color and the pearl-gray of the sky enhance the whole range of greens of the vegetation. The shockingly acid green landscape of Soutine’s A Windy Day drags us inexorably inside his painting. The artist makes us feel the gusts of the wind, as everything was bubbling. “Everything dances around me as in a Soutine landscape”, a phrase about drunkenness uttered by Modigliani, a friend and drinking companion of the painter.

Futurist Wind

Umberto Boccioni introduces the vortex of modernity. Instead of dismembering and multiplying forms like the Cubists, the futurist synthesizes the anatomy of space in a whirlwind fusion of bodies and objects. The space of the modern city – with its chimneys, scaffolding, men and horses – is exasperatedly mixed in the aerodynamic earthquake of its The City Rises from 1911. The masses deform under the pressure of the atmospheric currents. The myth of the wind is changed: no longer divinities like Aeolus, Borea or Zephyr; no longer romantic or impressionist atmospheric force; the wind is now the fibrillation of new technologies. Everything becomes a wave of movement, a robbery of the wind. The figures on the train are but oblique lines, fanned with adrenaline that dart across the canvas. Those who go, Boccioni seems to tell us, always go, projected forward while carried by the wind – they are present and future at once.

Wind and Passions

What love has got to do with the wind? A wirlwinding snake in Sappho; a light breath in Dante’s song of Paolo and Francesca; a gust that sticks to the dress of the woman in Montale’s Wind and Flags: wind has represented love through time. In the furious brushstrokes of the Bride of the Wind (1914) by Oskar Kokoschka, everything is wind and everything moves without distinction between subject and object. Overwhelmed by the amorous failure with Alma Mahler – in whose coils of portentous muse and crushing seductress many end-of-the-century spirits fell, from Gropius to Nietzsche, from Berg to Werfel – the Austrian artist portrays himself with her. She is a beautiful vampire of love in a cyclone, calmly chaotic with clouds crumbling around her body. She is a real obsession to the artist. Outside his studio, Kokoschka would even carry a rag doll representative Alma. A proxy, dead without a soul and yet a living spirit, this grotesque puppet was a ghost of a dead wind of passion, which never blew to begin with.

September 30, 2021