Cosima zu Knyphausen and her imprecise skeletons

The paintings of Cosima zu Knyphausen persuade you to ask what surrounds them, circulating motifs and subtle atmospheres, dismissing style.

Before anything else, we need to make clear that the poetic expression of the title is not of our making. During a recent studio visit at the residency of Fern in Brussels, the artist Cosima zu Knyphausen (born 1988, based in Berlin) surprised us when she mentioned “imprecise skeletons” to describe what surrounds her painting practice. The metaphor did it for us; our feelings towards her pictures became clearer, no matter the “imprecision” in the thoughtful analogy.

Nobody said that art should be about something – apologies to the late Arthur Danto – and what strikes us in Knyphausen’s painting is the atmosphere each of them creates rather than any clarity in their message. This is not to say that they’re mute. They are not asymptomatic. The “skeleton” in the equation is there, intended as a framework of references, motifs and interests in her iconography and iconology, which we’ll analyse more in depth in this article.

However, before moving from one painted theme to the other, it is essential to mention how Knyphausen shows that a personal aesthetic signature is no longer necessary for a painter in the 21st century. Pictures can be treated individually, she seems to say. They can be freestanding moments rather than pieces making up an identity of forms – for previous examples of 21st century style turndowns, see painters like Laura Owens and Jana Euler. If nothing else, when formal traits reoccur in Knyphausen’s paintings, they demonstrate her attitude of detachment from figurative picture making; see for example her typical blurry brush strokes, the empty canvas space she intentionally leaves in respect to the figure, material intrusion in the form of staples, eggshells, and potshards mixed with the paint, concentric framing marked by bold colors. We are awakened from the illusion of figurative painting, only to be put in the specific mood of each picture.

Landmark images

After graduating from art school, where she was sure she’d become “anything but a painter,” (her words) Cosima zu Knyphausen found an excuse to eventually become one by dealing with her native Chile. Two exhibitions, both in 2017, one at Sattler & Pötzsch in Leipzig and the other at Die Ecke in Santiago presented a series of paintings whose iconography directly drew from the Romantic views of Chile by the 19th century German painter Johann Moritz Rugendas. Despite the exoticism of a man from Augsburg in 1800’s Latin America, Rugendas’ pictures of the Chilean country-to-be found fertile ground in the nationalistic movement and de-facto became Chilean national heritage; a crucial anecdote for Knyphausen, whose main interest here seems to be how iconic motifs circulate through art. Not unlike the Buddha on TV of Nam June Paik, her paintings from this series are as much about the circulation and appropriation of iconic images as they are depictions of something. Paik’s buddha, writes Anna Mirzayan in a recent review, reflects the ideology of Silicon Valley today in a way that is for us similar to what happens when nationalistic ideologies claim images as their own.

To confirm that atmospheric sketches on canvas are not sufficient words to describe Knyphausen’s artworks, we can tell an episode from Rugendas’s art market history. A few years ago, a few of his paintings depicting scenes from Lima, Santiago and Valparaiso were auctioned in London. A Peruvian entrepreneur attempted to acquire them in order to place them where he thought they belonged: Peruvian land for the state of Peru. However, prices at auction skyrocketed and the plan fell short. A Chilean collector ended up with them – a setback for the Peruvian buyer considering the rivalry between the two countries. As a comment to what some might see as nationalistic nonsense, Knyphausen re-painted the works for the show Cuadros para Peru, inspired by those paintings and their recent history. Certain Rugendas motifs repeat in the artist’s paintings, yet they are rendered in different forms, suggesting her medium stands for something more; images need to be repeated enough to shape into collective memory.

Not a Room of One’s Own

There is a fantastic studio in the Ducal palace of Gubbio, which was designed by the Duke Federico Da Montefeltro in the 15th century and executed with precious intarsi by the finest craftsmen at the time. Erudition and contemplation in the seclusion of an expensive room away from business and parties was reserved to the powerful men. Cosima zu Knyphausen shifts the topic of the studio (or studiolo) to women and to less bombastic personalities than a Machiavellian Renaissance ruler with lots of money.

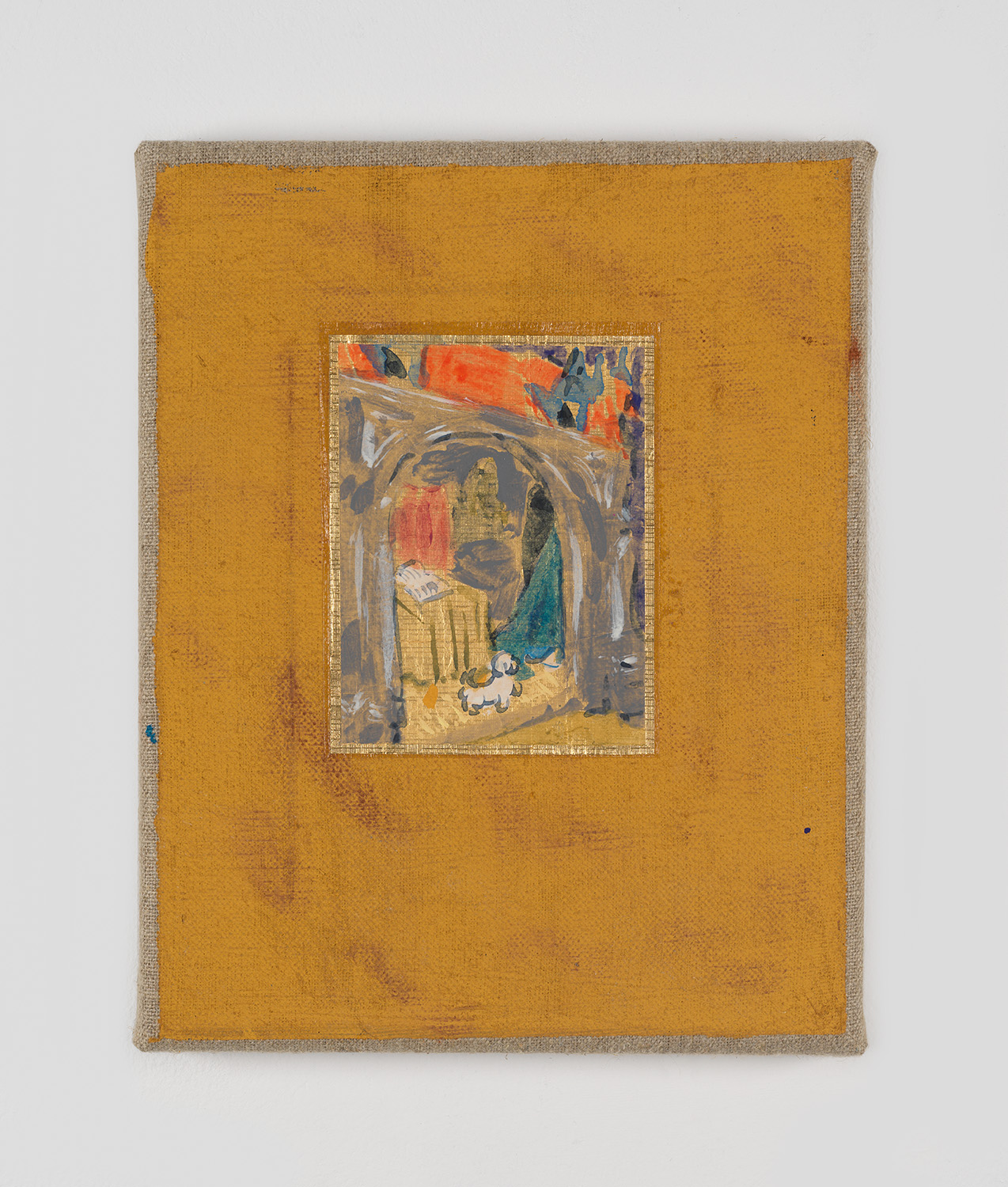

Her women who read, which she recently showed at the galleries Weiss Falk in Basel and Piloto Pardo in London, are semi-forgotten female thinkers from the European past, but also characters from the artist’s life. Knyphausen confirmed to us that the Medieval poet Christine de Pizan has been an inspiration for years, from her literary achievement to the occasional peeks into 600-year-old banal situations found in her writings – Christine leaving the studio as her mum calls for supper is one of Kynphausen’s paintings, and a tribute to the intimate everyday the Medieval intellectual reports in her book.

There is a good amount of conscious feminism in citing and making figures like de Pizan re-emerge from the depths of the past, yet Kynphausen’s attitude is far from literal militantism. Again, the skeleton of references is rather imprecise, and she confirms that motifs are mostly excuses to paint. Nonetheless, the critique to pictures and past ways of picturing, that is, the male gaze on women reading in private spaces, does emerge (notable art historical examples are Veermer’s Woman Reading a Letter, the slightly awkward depiction of Caterina da Siena by Rutilio di Lorenzo Manetti, or even the more modern and even more awkward Girl at Mirror by Norman Rockwell). We are astounded by Knyphausen’s choice of a specific private moment as a subject, mixed with a political message, and rendered in her signature atmospheres.

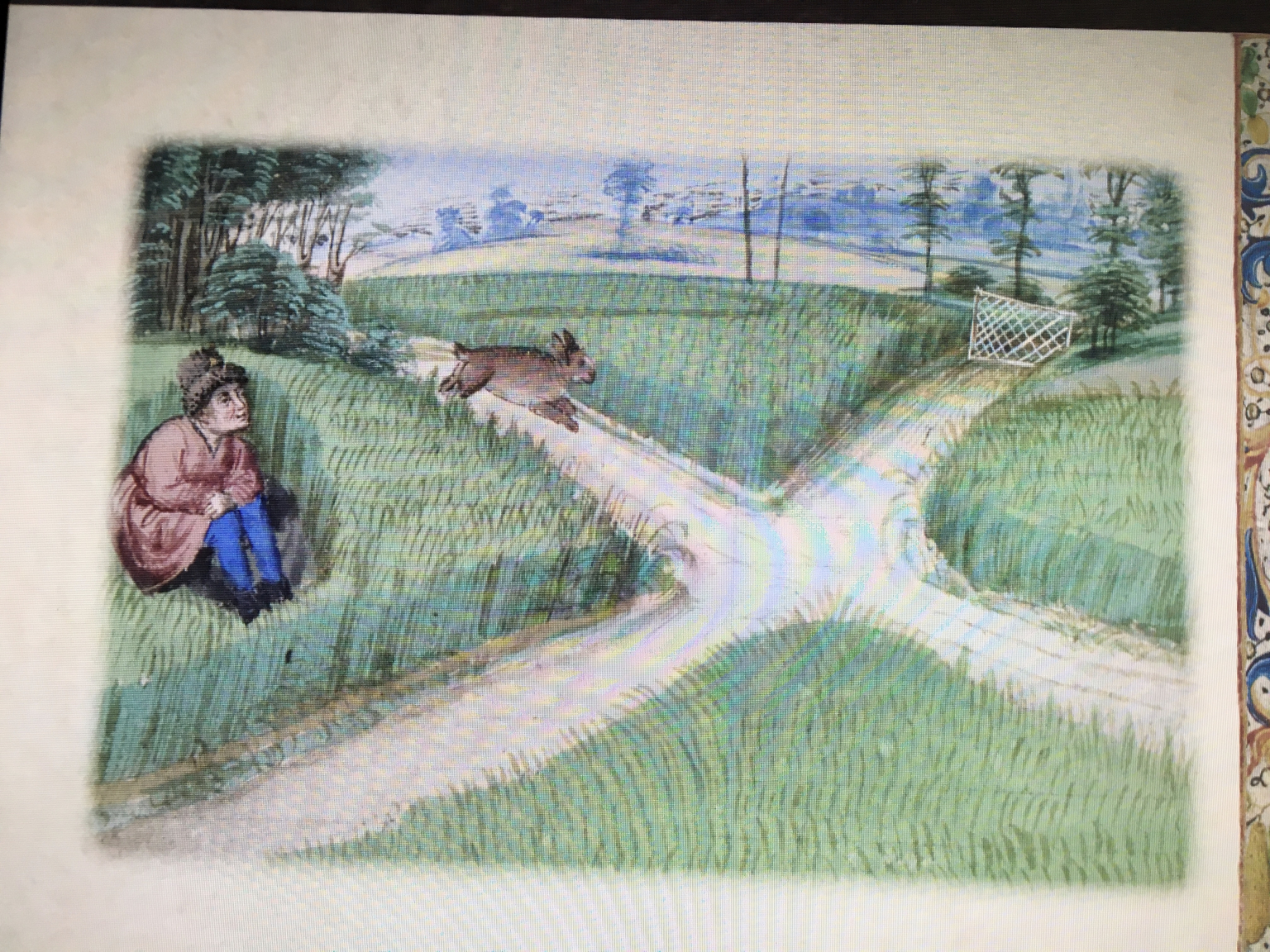

Her current trip to Brussels has been marked by occasional visits to the Belgian Royal Library, which hosts precious manuscripts of Christine de Pizan, but also old illuminations whose comic book quality must strike a chord with an artist who, as a youngster, aspired to get into the graphic novel medium. The illustration of a crossroad from a Medieval book she sent to us vibrates with atmospheric character just like only her paintings can do. Her residency at Fern and collaboration with Belgian Frizbee ceramics will culminate in brand new ceramic works, which already make us curious on the ways Knyphausen will translate her fortunate painting attitude into the new material.

December 9, 2021