The immaculateness of Andrea Mantegna

On the youth of Andrea Mantegna, between the page and the stone, in the demystification of the antiquarian obsession

Every artist has their own secret. The most seemingly straightforward of them is the most difficult. Relying on Gide’s critical thesis, Charles Du Bos suggests that nothing is as mysterious as a glass bottle filled with pure water. Andrea Mantegna is like a geometric solid made of crystal; each face strictly responds to a numerical rule, but in reality the numbers escape us into multiple reflections.

– Maria Bellonci

The first notion about the city’s history imparted to every young Paduan during compulsory schooling is that the founder of the city, Antenore, is not under the graveyard dedicated to him. It seems essential for the inhabitants of Padua to be fully aware of the impostor who occupies the tomb of the noble Trojan founder of the Venetis. Crowds of children on a school trip to the historic center astonishingly look at the idolized medieval aedicule, wondering who exactly is buried there. Most of the time the reply to them is simply “a dignitary”–in reality, a Hungarian warrior should be the answer. Sometimes, these children are told that next to Antenore’s grave Jacopo Ortis also rests–known as Girolamo Ortis, he was a medicine student who took his own life in 1796 and famously inspired Ugo Foscolo for his namesake novel. Since ancient times, the presence/absence of its founder has been fundamental to the city of Padua, and it could introduce Andrea Mantegna’s passion for gravestones as “sweet and furious”–two adjectives with which Maria Bellonci pointedly described the temperament of the artist. Padua has always longed to possess its own origin and sought it out in the land.

[More on Andrea Mantagna in this article: the message hidden for the artist by Antonello in Saint Sebastian’s navel. Ed.]

An obsession overwhelmed the city in the 15th century when Mantegna lived: finding and collecting antiques. The Urbs Picta flourished in the first centuries of the Roman Empire, and it is to be thought, or at least it was for its 15th century medieval yet very precocious humanist citizens, as a skin full of small wounds; from each of these lacerations came Roman epigraphs, coins, marble feet, bones–and what bones, those of Tito Livio! Padua was a meadow dedicated to treasure hunting, enriched by everything that was brought in from the Greek lands, including the precious manuscripts by refugees that sought asylum from the upheavals in the East.

The past was tangible, emerging from the fields, along the embankments, made of metal and stone–tombstones to be precise, which, like semi-darkened text frames, rose from the ground. In this fervor, the young Mantegna was a partner of the most obsessed of all proto-antiquaries: Giovanni Marcanova and Felice Feliciano to name two, with whom the artist made the famous journey to the shores of Lake Garda in the 1460s to the location described by Feliciano in the Iubilatio; the trip became a descent into the Elysian fields of the antiquarians, with roses, palm trees, fragrances of paradise and many, many epigraphs.

To enter the thoughts of the arrogant, regretful, resolute, loyal, and far-sighted old master Mantegna, it is necessary to have in mind the dualism in which his passion was immersed: on the one hand the stone, on the other the manuscript. He loved these two things only–in addition to his wife Nicolosia perhaps. He lived because of them, and their common textual element.

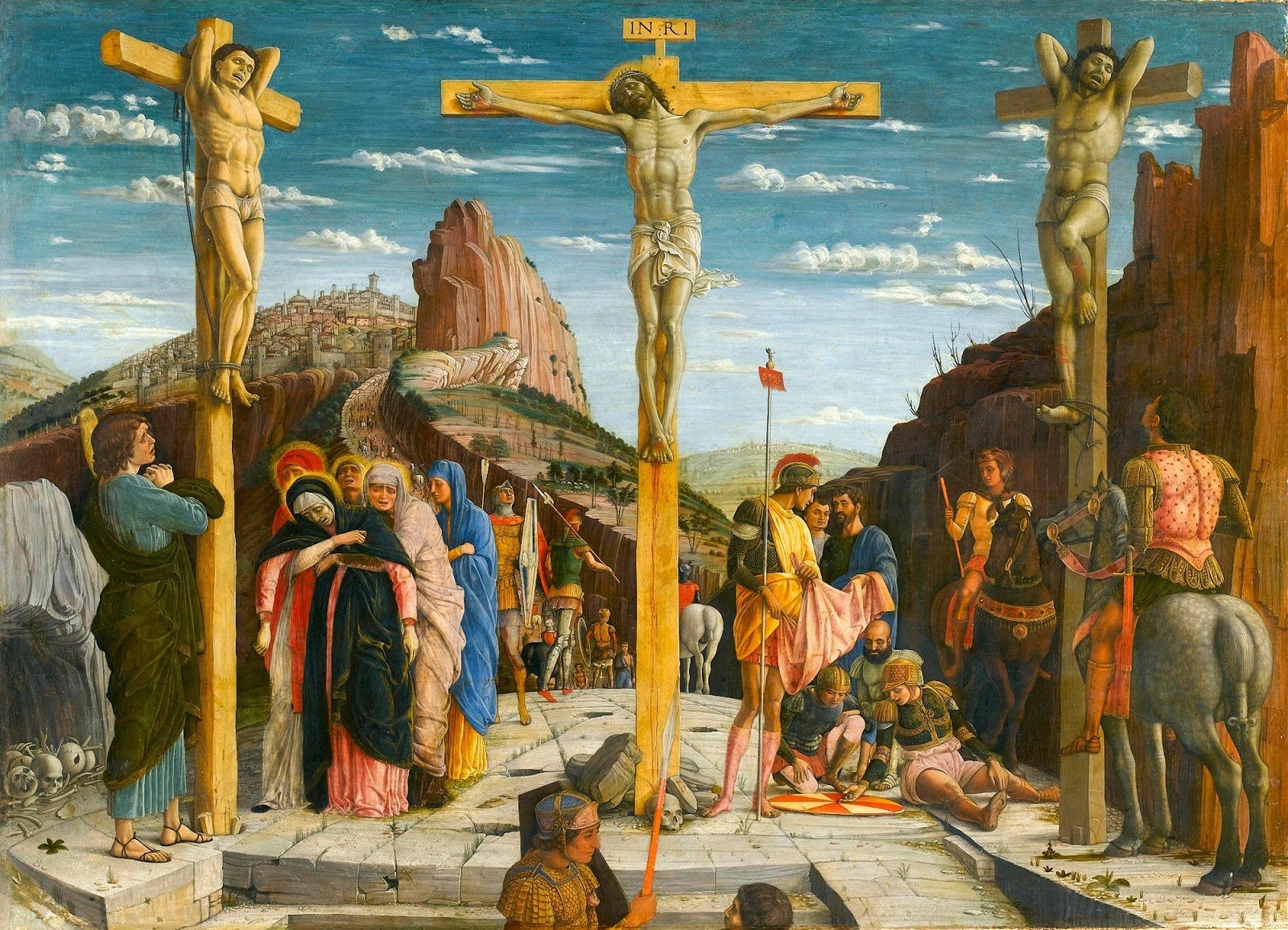

Mantegna has warranted plenty of descriptions for his work and persona: “the most perfect of the great masters of the Italian 15th century,” and “unapproachable” by temperament at the same time (Philippe de Montebello); the one who left “a pointy and painful legacy, which remains beneath the surface of European art but continually reminds how much of it is, by comparison, only pleasant and optimistic.” (Lawrence Goring); “The most consequential and inspected artist of the Quattrocento.” (Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti); the “unscrupulous naturalist.” (Adolfo Venturi). He had the singular ability to portray stories and people with no pity, showing a lucidity that, for centuries, was unbearable to a few critics. But in order to be so realistic, to become a “supreme psychologist” (Guido Piovene), Mantegna relied not on reality itself but, albeit entirely cerebrally, on the already codified textual language found on stone and page. This is where his greatness resides.

What is exactly hidden behind the artist’s obsession with antiques? Is it the layout typically found in some of them, a series of windows and frames normally used for text, but which Mantegna appropriates to put forward a precise aesthetic argument? In the Martyrdom and Transport of San Cristoforo in the Ovetari Chapel, the narration is divided into two scenes whose separation is symbolized by a fluted column that cuts the composition like the fold of the sheet in a booklet. The sky is of a singular grape color fading towards the blue, which recalls the color scheme of the pages of the precious purple codes where the parchment was dyed in a mixture of carmine and blue. The city also degrades in this painting, from medieval architecture in the background to Roman architecture in the foreground; the building’s facades are rich in tombstones and marble decorations, which Mantegna certainly took from the study of sarcophagus. On the same wall are the busts of dignitaries in quadrangular box niches, surrounded by medallions in polychrome marble and Istrian stone according to a fashion of the time. A few decades later Annibale Maggi da Bassano, an architect and antiquarian whose only goal in life was to include Tito Livio in his own genealogical line, used those same medallions to decorate the Casa degli Specchi in via del Vescovado; for centuries, the house has been considered haunted, including by the present author’s mother–it is no coincidence that similar medallions decorate Ca ‘Dario in Venice.

Mantegna also uses a bipartite composition for Saint Sebastian, now at the Kunsthistorisches in Vienna. The natural stone from the Monselice hills dominates the left-hand side, while the right-hand side presents the humanly sculpted stone of the Roman Empire’s broken marbles. In this work, the motif of the harvest cherubs and the pagan statue’s foot, a ruin also found in Saint Sebastian at the Louvre, appear for the first time; these are elements directly referencing the Roman archeological findings preserved between Aquileia and Padua.

Over the years, Mantegna’s compositions gradually came to resemble the illuminated page of a codex, where architectural windows, marble imitations, doors, friezes, and other antiquarian crazes ideally corresponded to a textual page crowded with letters. For example, this finely weighted fullness is found in the episode of the Circumcision in the Uffizi Triptych, as well as in the Triumphs at Hampton Court Palace. Despite the richness of his works, Mantegna never falls into the trap of compositional promiscuity. Writing about the Camera degli Sposi in Mantua, Guido Piovene suggests that the painting is rather “a portrait divided into several large squares, [or] a novel narrated in a few chapters.”

We can imagine the young Mantegna wandering around Padua, paying more attention to the masonry shops and stonecutters than the artworks of Giotto and Giusto, reaching the Euganean quarries on horseback, fascinated to the point of depicting them in his Madonna delle Cave (Madonna of the Caves). He must have studied the rocks from life, but also in their previous representations, since he trusted the synthesis of reality in painting, just seemingly thirsty for detail. Leo’s Bible, a Constantinopolitan manuscript dating back to around 940 AC, now preserved in the Vatican, shows a miniature of Moses receiving the tablets: the depicted heights greatly resemble those in the Agony in the Garden by the Paduan artist.

We can also imagine Mantegna flipping ancient Roman coins where architectures and decorations were depicted on the opposite side of the Emperor’s faces: depictions he must have been translating in his frescoes–take the crossed cornucopias and eight-pointed stars in the Assumption of the Virgin in Padua as examples. Mantegna did not limit himself to copying the ancient, but perfected it and brought it into common use together with the team of his peers: copyists and twenty-year-old antique dealers, with whom he shared his passion. In his works, whenever he painted inscriptions and cartouches, the so-called Mantinian littera appeared: a character with large proportions and with graces to complete the strokes, the non-closed P, and an airy succession of letters inspired by the handwriting of the first decades of the Roman Empire.

Although some critics have called Mantegna a romantic, the more lucid have noticed how his antiquarian passion does not betray any emotional impetus, any “episode of unsupervised fervor,” to use Ragghianti’s words. Mantegna is a realist who finds in antiquity, either reproduced on the pages of a codex or on the back of a coin, a vocabulary of formal motifs and solutions so solid as to allow him to purify himself of the fashion of his contemporaries. He uses the past, however sumptuous, to cleanse the present.

Of all the ancient masters, he is perhaps the one who best helps understand that abundance of visual elements is not abundance of meaning–the richest painting can be like a prime number, a glass bottle full of water. Mantegna was able to be at once the painter of the Triumphs and his tender Madonnas (among the sweetest of every century), showing he could be the artist of no symbolism. In his works, the fragment of a marble foot is an archaeological finding, not a vanitas; a fig leaf is not a symbol of messianic peace; a putto is just a fat, winged child. The renunciation of the symbol for the sake of an inventory of objects chosen for pure affinity led Mantegna to immaculateness, about which Sir Philip Anstiss Hendy wrote:

In the frescoes of the Eremitani church, the eighteen-year-old boy […] is the first and greatest of the pseudo-classicists, and, while he looks inwardly at a world of his own creation, only this detachment from humanity is what makes possible his immaculate design.

To read a Mantegna fresco is not to unfold a narrative inherent in each represented object, but to grasp the overall design in which objects are only bricks. No detail is as good as its container; even the tombstone exists for its role as a frame, and the content is useful to define it chromatically. The pomp is the design of a pomp, a space is the design of a space. Mantegna is not a complex painter in virtue of the richness or philological accuracy of his iconographic repertoire; he uses perspective masterfully but his compositional skills cannot be reduced to this mere logic; his realism is cerebral, and carries with it the synthesis in painting learned by looking at the world depicted on the page, or engraved in the stone. His works still challenge the viewer to think of a space that is different from both dream and symbolic object, away from vision-deduced reality, to approach, not without difficulty, a world built from textual windows and frames.

Bibliography

Andrea Mantegna, a cura di Jane Martineau, Milano 1992

M. Bellonci, Il “solenne maestro”, in L’opera completa del Mantegna, Milano 1967

I. Favaretto, G. Bodon, Cultura antiquaria e immagine dell’arte classica negli esordi di Mantegna, in Mantegna e Padova, 1445-1460, Milano 2006

www.academia.edu/15503060/Andrea_Mantegna_e_la_maiuscola_antiquaria_in_Mantegna_e_Padova_1445_1460_a_cura_di_Davide_Banzato_Alberta_de_Nicol%C3%B2_Salmazo_e_Andrea_Maria_Spiazzi

April 13, 2022