Walter Monich: from Milan’s Duomo to Angevin Abruzzo

Stylistic analyses suggest Walter Monich is the author of the Annunciation in Tocco da Casauria, today in the Bargello Museum

Collecting and attributing history of the Annunciation in Tocco da Casauria

We are negotiating the sale of the Guardiagrele group with Mrs. Gardner at the price of 35,000 lire. Thus opens a letter dated 28 April 1906, written on the letterhead of Giuseppe Sangiorgi Gallery in Rome. The subject of the negotiation was an early 15th century stone Annunciation from Tocco da Casauria, a village of two thousand souls at the foot of Monte Morrone, in the Italian region of Abruzzo. The addressee of the message was Corrado Ricci, director of the Gallerie Reali Fiorentine; he wanted to secure the work for the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, the top state collection of ancient sculptures. In short, the antiquarian was trying to close the deal, wishing to avoid finding himself in “an embarrassing condition with our American client”: he therefore informed Ricci of the fearsome competition from Isabella Stewart Gardner, hoping that the ministerial official would manifest his interest in the public acquisition. The Annunciation of Tocco da Casauria had other pretenders as well, among whom Sangiorgi recalled Giovanni Tesorone, former director of the Museo Artistico Industriale in Naples, a native of Abruzzo. With a somewhat aggressive strategy, the merchant also hinted at favourable treatment for the State: if Gardner had been offered the sculpture for 35,000 lire, and Tesorone for 25,000, the Roman firm would be willing to lower the price even further, down to 20,000 lire, “provided that this work remains in Italy”.

In urging the intervention of the Ministry of Public Education, both Ricci and Igino Benvenuto Supino, director of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, explicitly insisted on the need to prevent the exportation of a work that, at the time, was attributed with absolute certainty to the goldsmith and painter Nicola da Guardiagrele; indeed, this ‘is the only one known to have been sculpted by him’ in stone.

The work is unique, well-preserved, remarkable for its dignity, and worthy of a great museum. The Museo Nazionale in Florence is the only Italian museum that shows the development of Italian sculpture from the beginning of the Renaissance to Bernini. Every most celebrated sculptor is represented there by some admirable piece. This distinguished Annunciation by Nicola should therefore not be missing, because Nicola worked in Florence and was a pupil of Lorenzo Ghiberti. Once abroad, how will there ever be another sculpture by Nicola, if this is now the only known one?

Since the Annunciation was still unpublished, it is to be assumed that the attribution to Nicola da Guardiagrele had been circulating for some time among antiquarians, amateurs, and potential buyers. What made the negotiation complex, however, was an unforeseen event. By 23 May 1906, the work was subject to judicial seizure, as it was suspected to have come from a theft committed in a church in Abruzzo. Only when the seizure was lifted could the State acquire it, on 26 March 1907, for the sum of 16,000 lire.

If I have chosen to discuss the Annunciation starting with its arrival in the Bargello museum, it is because the archive papers evoke the attraction this sculpture exerted in the flamboyant Roman art market of the early 20th century. On the other hand, the debate on Nicola da Guardiagrele as a stone sculptor came to life around that time, after the publication in 1901 of the six stone reliefs then in the garden of Casa Patini in Castel di Sangro and now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence–erratic works like the Annunciation in question; also destined to leave the province of Abruzzo for the Tuscan capital, after their passage through the antiques market.

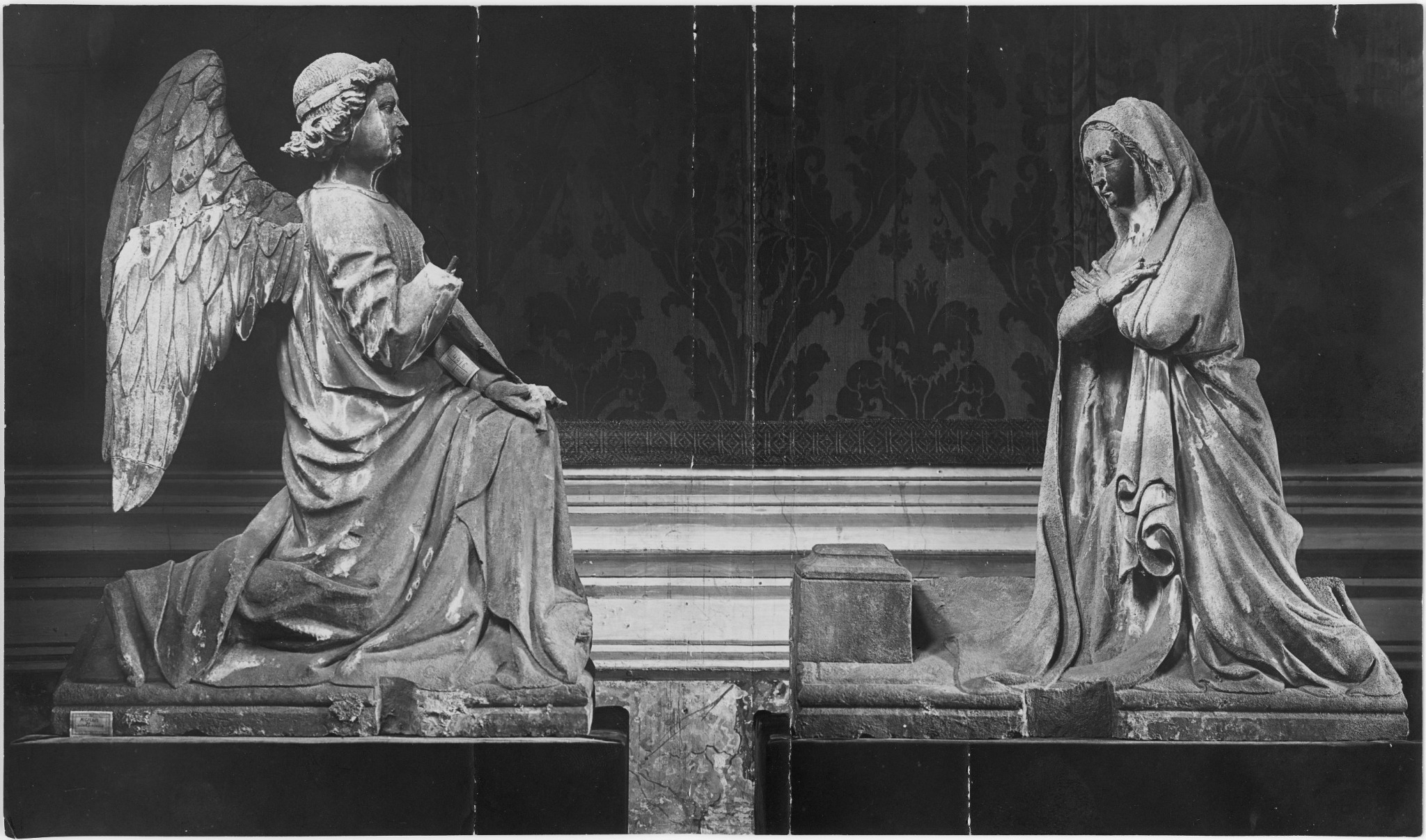

The Annunciation in Tocco da Casauria is indeed one of the most interesting works of early 15th century sculpture in this region. Carved in high relief, the scene consists of two separate blocks of Maiella stone, in which the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary are carved. The back, flat and unworked, must have adhered to a wall or, more likely, to the lunette of a portal. The two protagonists of the sacred scene are kneeling on two separate platforms, rendered in foreshortening, attached to the figures. What is puzzling is the shape of the lectern, unusually consisting of a low moulded plinth, devoid of any joint for a pillar. A lectern might have been painted on the back wall. I do not believe that the unusual support is the result of tampering, perhaps of an antiquarian restoration, aimed at flattening the remains of a stone lectern that has since been reduced to a fragment: in a Sangiorgi photo, which shows the group still blackened and awaiting cleaning, the plinth already appeared this way. Again with regard to the state of conservation, on 8th March 1907, in view of the shipment of the two sculptures to the Bargello, the Rome antiquarian Sangiorgi advised that three detached fragments had also been placed in the crates. From the reply of Giovanni Poggi, the new director of the museum, we learn that two fragments belonged to Gabriel’s right wing (we now see them reassembled), while the third was the “lily branch that the angel held with his left hand” (this piece, however, does not seem to have reached us). The Archangel is also missing his blessing hand, and there are numerous gaps in the hem of his robe. On the other hand, the Virgin has lost the index and little finger of her right hand. Both bases are chipped in the middle segment.

The lively interest in the sculptural group in the early 20th century is confirmed by the four articles published in the year of its arrival in Florence–almost all of them, however, are extremely elusive in their interpretation of the style. In the newly-born ‘Bollettino d’arte’, Arduino Colasanti actually aligned himself with Ricci and Supino, reiterating the attribution to Nicola in the name of presumed and unspecified ‘imprints of Tuscan influence’. The Annunciation was presented by him as a sort of ballon d’essai, as he was unable to identify “in the whole of Abruzzo another work in stone, which, due to its technical and stylistic characteristics, could be said to have come from the hands of the same artist.” The Roman scholar was, however, able to provide more precise indications on the provenance: ab immemorial, the Virgin and the Announcing Angel were found reused in a shrine at the entrance to a private garden near the church of San Domenico in Tocco da Casauria, in the current province of Pescara. By the second half of the 19th century, ownership of that garden had passed from the Filomusi family to Baron Cedino Bonanni, who had married Lucia Filomusi. It was Bonanni himself who, in 1904, sold the Annunciation to a leading Roman antiquarian, Alfredo Barsanti, who in turn sold it to Sangiorgi. In light of this information, it is probable, albeit without certain evidence, that it originally belonged to a church in that town, perhaps the church of San Domenico, which had existed since at least 1408, although the current main portal is dated 1495.

All caught up in a fruitless local controversy, however, Pietro Piccirilli, to whom the Annunciation had been known “for years,” absurdly dated it to 1495, if not “shortly after.” As a correspondent of the Ministry, the scholar was aware of the details related to the judicial seizure of May 1906: in that instance, Sangiorgi would have declared that the group was once accompanied by a fillet with the signature of Nicola da Guardiagrele; Piccirilli, however, preferred to keep the work anonymous, not believing in the “little story of the strip with the name of the illustrious Abruzzese artist: a strip that never existed”. In short, the problems of artistic authorship and dating began to be discussed. Another artist from Abruzzo, Vincenzo Balzano, suggested his own intricate hypothesis, according to which there were two Nicola da Guardiagrele: the goldsmith and painter, active in the first half of the 15th century, and a sculptor, active towards the end of that century. In this regard, reference is made to the problematic passage in Vasari’s Giuntino about a Niccolò della Guardia, a pupil of Paolo Romano and supposed co-author of the tombs of Popes Pius II and Pius III, today in Sant’Andrea della Valle in Rome. To this fictitious personality Balzano assigned the Annunciation in the Bargello museum. Finally, to return to the national dimension of the debate, from the pages of Adolfo Venturi’s “L’arte”, an anonymous reviewer of Colasanti’s work stated flatly that the group seemed rather “inspired by the art of northern Italy”. Despite the bluntness of this judgement, this seems to me to be the most promising lead for a correct interpretation of the work. And yet, the erroneous attribution to the Guardiese artist was reiterated during the first half of the 20th century by the aforementioned Balzano, Ignazio Carlo Gavini, Filippo Rossi and, above all, Enzo Carli. In an important article, where more serious philological tools were used to lay the foundations for a catalogue of Nicola da Guardiagrele as a stone sculptor, Carli proposed a comparison (rather unconvincingly, as a matter of fact) between the Bargello Archangel and its counterpart in the portal of Teramo Cathedral, on that occasion rightly returned to Nicola.

The interest in the Annunciation of Tocco da Casauria cooled down in the second half of the last century, when, on a more general level, the debate on Nicola and early 15th century sculpture in Abruzzo also started to wane. This may seem paradoxical, if we bear in mind that in 1951 a document was published that should have prompted a re-examination of the issue: the contract of 1456, through which Nicola de Argentis de Guardiagrelis committed with the Chapter of the Cathedral of Ascoli Piceno to create a stone ciborium for the high altar of that church. The now elderly artist died before completing the commission, which was to include the carving, in Maiella stone, of a pair of stylised lions, four figured capitals and, above all, seven figures, of which at least five in the round. Although it was now certain that Nicola had also been an appreciated sculptor, the corpus discussed by Carli, including the Annunciation of Tocco da Casauria, was put to one side. In the last twenty years scholars went back to analysing this work, albeit with the sole purpose of reasonably expunging it from the Abruzzese master’s itinerary, without, however, ever proposing alternative attributions, at times highlighting the need for more in-depth research. Gaetano Curzi appropriately pointed out German stylistic features in the face of the Archangel; the connections he established with the Florence of Nanni di Banco and Niccolò di Pietro Lamberti are, however, perhaps less adequate. Gina Lullo finally grasped the similarity of the Annunciation to contemporary Lombard sculpture, especially in the schematic definition of the locks of the Madonna’s hair and in the calligraphic elegances of the veil. This lucky intuition, however, was not further explored, and so Francesco Gandolfo claimed that if the reference to Nicola seemed “improbable” to him, the two Bargello figures would still be “related to the manner” of that artist, in light of the comparison already established by Carli with the figures of the Teramo portal. It was only two years ago, thanks to an exhibition in the Marche region, that it was possible to examine the work more closely, since, in the Florentine museum, it is located very high up in the Salone di Donatello.

Formal analysis and attribution: Walter Monich in Milan

I believe that the absence of references to Ghibertian culture, and Florentine culture in general, makes it impossible to refer to Nicola or even to any artist from his circle altogether. The Virgin’s voluminous mantle, the hem of which folds in on itself in hyper-gothic curves; the physiognomies characterised by tiny mouths and equally tiny chins, which sprout above the soft dewlap; or more, the way of carving the stylised locks of hair, to then frame the angel’s face with a fantastic crown of curls more akin to rampant kittens, make one think rather of an artist of German origin, who can be identified as Walter Monich, the artist who had left at least one important work at the foot of Monte Morrone. The sequence of documents and epigraphic references describing the Italian itinerary of this Teutonicus is so consistent that it leaves almost no gaps. After his ten-year militancy on the construction site of the Duomo of Milan, from 1399 until at least 1407, followed by a stop in Orvieto between 1410 and 1411, Walter was already in Abruzzo in 1412, when, under the name Gaulterius de Alamania, he signed the Caldora family monument in the abbey of Santo Spirito al Morrone, near Sulmona. After Laura Cavazzini was able to compare at least two statues now in the Duomo Museum in Milan with the reliefs of the Abruzzi tomb, the intuition of Adolfo Venturi, who was the first to realise from the documents that the Walter of Milan and the one of Sulmona (Gualterius, according to the Latin version of that name) were the same person, became real. Today, therefore, we can say that we are familiar with the style of this sculptor, who had an “imaginative temperament, and was a little rough and ungrammatical in his execution, but capable of coming up with striking gimmicks”. Let us proceed with order, and try to place the Annunciation in his repertoire, and then verify that the Abruzzi valleys bear no further traces of his passage.

“Gualteri[us] de Monich teutonich[us] magist[er] a figuris” appeared for the first time in the accounts of the Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo di Milano on 28 March 1399, receiving a fee of 3 lire and 4 soldi for a Seraphim, which he executed pro maiori parte: a work that is not easy to identify, but almost certainly destined for one of the three large windows of the apse of that cathedral. Perhaps this first commission served to test the skill of this newcomer and most probably a native of the Munich region, as can be deduced from the toponymic indication ‘Monich’, ‘de Monicho’ or ‘de Monaco’, which accompanies his first name in documents differing in chronology and territorial scope. The massari of the Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo di Milano hired him in May of that same year, with a daily salary of 8 soldi. The Fabbrica was in need of new sculptors after the death in 1398 of both Giovannino de’ Grassi and Giacomo da Campione, leading figures in the first phase of construction, as far as the design and execution of the Duomo’s oldest sculptural complexes were concerned. On the other hand, the sudden call from another building site in the Po Valley, such as that of San Petronio in Bologna, had led to the departure of Hans Fernach and Alberto da Campione from Milan as early as 1393–the German artist, after having made a temporary return to the Visconti capital, left again (and apparently, forever) in 1395, while Alberto would only return to the service of the Veneranda Fabbrica in the new century.

It was in this context that Walter’s arrival and rise in Milan took place. The simultaneous presence of the Frenchman Roland de Banille, the Venetian Nicolò da Venezia and other Lombardi such as Giorgio Solari, Matteo Raverti or the returning Alberto da Campione did not prevent him from becoming a leading figure for a few years in a construction site that attracted masters from all over Europe: from 1403 to 1407 he headed a team that numbered almost three hundred stonecutters. In a more secluded position there were other German sculptors, such as Annex Marchestem, who had also been in Milan for longer (in 1395 he had taken over the work tools that had belonged to Hans Fernach), or Peter Monich, Walter’s fellow countryman and possible pupil. Among the sculptures by Walter recorded in the Milanese accounts are a Prophet, paid on 15 May 1404, a “figur[a] magn[a] […] cum uno libro”, paid on 17 July 1406, and again a Giant, paid on 1 March 1407. Costantino Baroni and Herbert Siebenhüner searched in vain for such works in the wilderness of the Duomo’s statues, starting from the research of Ugo Nebbia, author of the first, monumental attempt at systematisation of that immense heritage. Rossana Bossaglia and Mia Cinotti, on the other hand, tried to identify the work of the craftsmen led by Walter in a large group of statues and statuettes in the Duomo Museum of Milan, which were in various ways related to Rhenish art. All of these attempts, however, clashed with the vagueness of the documents, which in no case made it possible to identify with certainty the works that had been remunerated to this artist. At the end of the last century it had to be admitted that in Milan “not a single work by the German sculptor is known.” Today we believe that the team Walter coordinated worked mainly on the pillars of the head of the choir, in front of the sacristies and in the north transept of the cathedral. This turning point in the research was marked by a comparative examination with his later signed work in Abruzzo, i. e. the already mentioned Monument of the Caldora family in the abbey of Santo Spirito al Morrone, dated 1412. On this basis, Laura Cavazzini was able to convincingly attribute to him the St. John the Evangelist and St. Thaddeus of the Duomo Museum, which come respectively from pillar 84, in the head of the choir, and from pillar 53, in the left transept of cathedral–one of the two statues, moreover, could be the “figur[a] magn[a] […] cum uno libro” dismissed in 1406. The voluminous draperies that wrap those two saints and the way the locks of the beard and hair are carved are very similar in the Sulmona reliefs.

The Bargello museum’s Annunciation appears consistent with these sculptures. The Virgin’s thick cloak, with the hem twisting around itself in concentric curves and then spreading like rays of sun down the side of the figure, is reminiscent of the thick drape worn by the Milanese St. John with a similar pattern of folds. The faces of these statues are characterised by a small round chin jutting out above a somewhat chubby neck, a tiny mouth and eyelids marked by a double contour line. The Evangelist of the Duomo Museum and the Bargello Virgin also resemble each other in the graphic pattern of the locks of hair, rendered through parallel lines–perhaps a reminder of the stylisations of Hans Fernach, whose works had been before Walter’s eyes for at least a decade. In any case, the culture these two German artists stem from may have some points in common. I also wonder whether the pose of the Archangel of Tocco da Casauria might not derive from one of the most fascinating and problematic sculptural groups of the first decades of the Milanese construction site, namely the Annunciation in the middle window of the apse of the cathedral, designed in 1402 by Isacco da Imbonate and Paolo da Montorfano, of which Alberto da Campione had only drafted the Gabriel in 1404–in that very year, Walter took over as head of the stonecutters. Finally, we could compare the oversized cloak of our Announcing Angel with the equally ample and thick robes of the Coronation of the Virgin in the front of the sarcophagus of the Caldora Tomb, dated 1412. The Annunciation of Tocco da Casauria should date back to a time shortly after that, marking the artist’s move to Angioino Abruzzo.

Walter’s luck in Milan must have run out in 1407, when the leadership of the stonecutters passed to Jacopino da Tradate, who would become the most important sculptor in Lombardy in the first half of the 15th century. At this point, Walter probably continued to work for the Veneranda Fabbrica, but in a marginalised position. Eventually he preferred to seek his fortune elsewhere, making his way south. The first stage of his migration, as mentioned above, is marked by the building site of the Duomo in Orvieto, where Giovanni da Campione and his son Martino, Bonino da Campione’s son and grandson respectively, had already arrived from Milan on 21 December 1409. Within a short time “Gualterius Johannis de Monaco theotonicus, bonus et optimus magister,” mentioned here for the first and last time with his patronymic, was also registered in Orvieto on May 3rd, 1410. In the previous days he had already demonstrated his talents, working in the loggia of that city’s cathedral together with a certain Giovanni Berti de Mediolano. Walter and his otherwise unknown companion were hired for the Orvieto building site with wages of seven gold florins and five and a half florins per month, respectively; on June 28th, 1410, the agreement was renewed for another ten months.

Walter Monich in Abruzzo

By luckily matching these archive documents, in 1412 we found the signature of ‘magister Gualterius de Alamania’ on the Caldora family monument in the abbey of Santo Spirito al Morrone. The burial was ordered by Rita Cantelmi ad laudem Virginis Mariae et in memoriam ipsius et filiorum suorum [in praise of the Virgin Mary and in the patron’s memory and her children], namely Giacomo, Raimondo and Restaino, the descendents with her late husband Giovanni Antonio Caldora. After the monographic study by Valentino Pace, and following the clarifications of the last twenty years, it does not seem necessary to discuss the scope of the commission or the typological novelty of this tomb elevated on columns in the local context. It will be enough to recall that in the abbey of Peligna, Walter found an environment that was undoubtedly less cosmopolitan than the Duomo in Milan. At the same time, it was also freer from the constraints that channelled the creativity of sculptors in the great Lombard factory, who, at best, were always subject to the assessment of their work by the fabbricieri, when not forced to proceed according to the graphic or pictorial design provided by third parties and assigned to the magistri a lapidibus vivis according to real competitions at auction. In Sulmona, his creativity must have run wild, otherwise we would not be able to explain such unusual solutions as the incredible predella where the sculptor arranged the high relief figures of Rita and his sons Giacomo and Raimondo praying. In the Caldora Chapel the German artist worked alongside a painter who must have been close to him: the imaginative fresco painter recently identified as Paolo dell’Aquila, who, just like Walter, was always “hanging between inspiration, impetus and negligence.” Both had indeed taken an eccentric path to International Gothic.

It was already clear to Abruzzo scholars that the Caldora Monument could not be an isolated work. In the middle of the 19th century, Angelo Leosini, on the basis of his study of manuscript sources, introduced two important aspects to delineate the central-Italian parable of ‘Gaulterius’. Firstly, the historian recalled the Monument of Niccolò di Giacobuccio Gaglioffi, executed in 1415 on commission of Maruccia Camponeschi, widow of the dedicatee as signed by the artist. The tomb, once in the church of San Domenico in L’Aquila, was lost in the 1703 earthquake. It is not, however, the 17th century manuscript by Claudio Crispomonti, to which Leosini referred, that has handed down the name of our artist, but rather a text by Anton Ludovico Antinori, who in the 18th century, among the surviving fragments of the tomb, believed he could read (without being too convinced) “Gualterus de Alamania”: an epigraph immediately related to that of the Morronese abbey. In short, there is perhaps no absolute proof that the lost Gaglioffi Monument was indeed signed by Walter, but there is at least the possibility that in 1415, only three years after the completion of the Caldora Tomb, this sculptor had again left his name on the tomb of another important local family, a fact that would attest to his immediate fortune in Abruzzo.

There is another more problematic passage by the same Leosini, who also attributed to Walter, this time only doubtfully, the Tomb of Ludovico II Camponeschi in the church of San Biagio di Amiterno, alias San Giuseppe Artigiano, also in L’Aquila. Dated 1432 and commissioned once again by a noblewoman (Beatrice Gaglioffi, mother of the deceased) this tomb presents, just like the Caldora Tomb, a sarcophagus supported by columns, adorned on the front with three paintings depicting the Coronation of the Virgin and eight saints; in this case the equestrian statue of the deceased stands on the ark, underneath a large canopied aedicule. Leosini’s assumption of attribution, which has had some success in modern literature, was in fact based on a purely iconographic and typological consideration: since Ludovico Camponeschi is depicted as a horseman, the possibility that the author of the statue was the same as the author of the lost monument of 1415, in which “the statues of the Gaglioffi were seen on horseback,” was taken into consideration. I believe that the kinship ties between the two families are sufficient to explain this convergence–Ludovico Camponeschi’s mother was a Gaglioffi herself. On the other hand, although the Camponeschi sarcophagus repeats the scheme of the Caldora sarcophagus, I share the opinion of those who point out the stylistic incompatibility between the sinuous figures in San Biagio di Amiterno and the only work signed by Walter that has been preserved; nothing ensures that our artist was still alive in 1432. In more recent times, there have been few attempts to expand Walter’s Abruzzese repertoire. Costantino Baroni attributed to him the Madonna and Child in the lunette above the southern portal of the Palazzo dell’Annunziata in Sulmona. That sculpture has indeed a rather Lombard touch, and the date 1415 engraved in the architrave would fit well with the artist’s chronology; but the naturalism of the Virgin’s face does not seem consistent with the stylisations of the Milanese statues, nor with the Caldora reliefs. In this regard, it should be kept in mind that in the early years of the 15th century, during the political transition that affected the Duchy of Milan after the death of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, several sculptors left the cathedral construction site, and more than one headed over to central Italy, like the aforementioned Giovanni and Martino da Campione or that Giovanni Berti who had travelled with Walter. It is perhaps more plausible to refer to our artist’s circle for the Saint Catherine of Alexandria in the Sulmona Civic Museum, which in fact recalls the Saint Thaddeus in the Duomo Museum in Milan, although the gently reclining head of the martyr is not entirely in line with the axis of the statues and reliefs examined so far.

Walter Monich and Nicola da Guardiagrele

It is therefore worth reconsidering, in this context, the impressive St John the Baptist standing out within a 16th-century aedicule on the facade of Santa Maria Maggiore in Guardiagrele, to the left of the portal. With regard to the abbey Morronese, we are on the opposite side of Monte Amaro. In his research on Nicola, Enzo Carli was struck by this monumental figure: “a kind of rural Zuccone, not without interest.” Without being able to anchor it to documents or epigraphic sources, Carli dated it to the early 15th century, and discussed it in relation to the environment from which the Guardia goldsmith was emerging. More recently, the Baptist has been assumed to be a possible product of Nicoli’s workshop, around 1430, recognising echoes of Florentine art, which do not seem so evident. The anchorite, with his contracted limbs and menacing air, recalls, if anything, one of the statues sculpted by Walter in Lombardy: the oft-mentioned Saint Thaddeus of the Duomo Museum in Milan, equally grim, and what is more, fearfully armed with an axe. Both are “somewhat rude, intensely expressive figures, covered by a mass of very voluminous, angular fabric, little inclined to be arranged in composed calligraphy”. The shavings of the beard and the way of ordering the strands of hair into crochets-like curls are now familiar to us: indeed, the head of the Baptist is almost the monumental version of the Saint Andrew sculpture from the left panel of the front of the Caldora sarcophagus. However, the physicality of the Precursor appears much more solid than that of the Lombard Apostle, whose cloak is also creased by a series of sickle folds, which we no longer find in Guardiagrele. The ‘rural Zuccone’, therefore, could represent a later development of Walter, to be dated perhaps to the 1420s and in any case a few years after the Caldora Tomb. It is easy to relate this statue to the renovation work on the western body of Santa Maria Maggiore, which began in 1426 and culminated in the Coronation of the Virgin by Nicola da Guardiagrele, once in the portal lunette and now in the Collegiate Church Museum. Certainly, the sculpture could not have been made for that niche, so we must consider an alternative hypothesis, which presumes its arrival on the facade at a later date–keep in mind that inside the church there was an altar dedicated to John the Baptist, existing at least since 1385, when the relative chapel, in the presbytery area, was under the patronage of the Orsini.

We then lose track of Walter. It is neither known how long he stayed in Abruzzo, nor whether he ended his career in this region. He had worked in Sulmona, and probably in San Domenico in L’Aquila in 1415, where traces of his presence can be detected two decades later in the aforementioned Camponeschi Monument in San Biagio di Amiterno, dated 1432.

On this occasion, an attempt was made to expand his activity to the villages of Tocco da Casauria and Guardiagrele. The question arises as to whether the aedicule of the Holy Countenance in the church of San Rocco, which is set on vitine columns comparable to those supporting the Caldora sarcophagus, could be attributed to his entourage–a mysterious ‘magister Conradus’ (another German name) is documented there from 1412, precisely when ‘Gualterius’ was travelling along the Via degli Abruzzi. The same question remains for the five column stems in the Antiquarium of Guardiagrele itself, and for those in the church of San Martino in Valle in Fara San Martino; the latter recorded on site by Piccirilli, who related them to an epigraph from 1411. After all, Walter’s certain presence in Sulmona, and his probable presence in Guardiagrele, may have impressed Nicola himself: something which, according to a shared hypothesis, helps to explain the Nordic influence of the Processional Cross in the Museo Nazionale d’Abruzzo in L’Aquila, from San Michele Arcangelo in Roccaspinalveti.

October 17, 2022