Six highlights from Paris Internationale 2022

Here are our picks from the eighth edition of Paris Internationale, one of the biggest and most ambitious yet

At the inauguration of the 2022 Paris Internationale, smiling faces were everywhere. “Paris is the new Paris”, someone whispered, referencing the city’s former dominance in the art world, yet adventuring into improbable comparisons with 100+ years old stories. Spirits were high indeed, as the arrival of Paris + marked a new chapter that came with a promise: the city will do it the Art Basel way, where, if things go as planned, galleries can fix those worrying cash flow issues that’ve been bothering their accountants for some time. We heard the promise was kept for some at Paris Internationale; as to the others, they either didn’t share the info or we couldn’t talk to them, lost as we were in the gargantuan crowd of the opening day and those that followed. More important than the gallery’s budgets were the artworks though, which impressed. Typically for emerging art fairs, but especially true for this year’s Paris Internationale, each booth felt like a little curated exhibition with a compelling narrative. We discovered and loved many, here are six of them.

Jannis Marwitz at Lucas Hirsch

The five Jannis Marwitz paintings (b. 1985, Germany, based in Brussels) presented at Lucas Hirsch will go to the United States. They were acquired by an American collector, who will donate them to a yet unchosen museum. Meanwhile, gestures of recognition like this acquisition might prompt the artist to bring his artistic discourse even further. Pat Metheny, a musician whose work has been showing how skills are just a starting point, reminds of Marwitz: The essence of his painting lies in poetry, which has a wide and diversified expressive field thanks to his mastery. He can “write songs” that are narrative, sentimental, ironic, disturbing, romantic, in minor or major key so to speak, but that always evoke humanity and its destiny with clear insight.

Aileen Murphy at Deborah Schamoni

We were struck by the metaphorical efficacy of Aileen Murphy’s paintings on view at the Deborah Schamoni booth. The artist (b. 1984, Ireland, based in Berlin) shows the ability to translate an idea into a pictorial image that is not graphic, or to follow the opposite path to reach an idea through pictures. In the work titled Age, tormented lips and teeth are the epicenter of a hinted body, crouched, immersed in a yellow cloud that speaks of a distant childhood. The signs of time emerge on a female body, a metaphor for human origin. In the booth, each painting seems to respond to a precise poetic need, avoiding a lazy rest on form and moving constantly to fulfill it.

Clémentine Bruno at Project Native Informant

Clémentine Bruno (b. 1994, France, based in London) recently declared that craft is a “vehicle for demoralisation.” Her paintings on wood in the Project Native Informant booth attest to her specific relationship with craft insofar as they challenge its inevitably traceable forms while retaining finesse; the traditional gesso on her panels seems scorched, pulled, the paint covering rather than drawing, yet with touching results. The potential drama in some of her works is stopped and broken through various means: pasted paper fragments, invitation to figuration, light brushstrokes that echo the beginning of something never begun. The booth also features what reads as a reference, a footnote even: an image of liturgical sculptures generally associated with devotion but collaged to show a somewhat violent blending of bodies.

Clémence de La Tour du Pin and Ingerid Kuiters at Femtensesse

Oslo-based Femtensesse brings to Paris Internationale works by Clémence de La Tour du Pin (b. 1986, France, based in Paris) and Ingerid Kuiters (b. 1939, Norway, based in Åsgårdstrand). The booth has a 19th century flavor, evoking an age where industrialism was young enough to produce objects that didn’t look industrial–it seems no coincidence that de La Tour du Pin studied at the Van Der Kelen school of decorative painting, which prides itself not to have changed since its 19th century foundation. The found umbrellas for the French artist and the found dolls for the Norwegian – the basis for their investigations – are either turned into little theaters for dreamy scripts (de La Tour du Pin) or surrealistic composites of solid simplicity (Kuiters). Although all the works are three dimensional, they are not exactly sculptural: They come off the wall and pull you close, directing you to each square inch of their detailed assemblage.

Irina Lotarevich at Sophie Tappeiner

Irina Lotarevich (b. 1991, Russia, based in New York and Vienna) produces symbolic and sharp volumes, often using hard materials such as aluminum or steel. At Paris Internationale, she presents a few container/benches and a sculpture on the wall titled Housing Anxiety: a box studded with keys on the edge and locks with no keys inside. The pieces on the floor feature casts of the artist’s skin, short circuiting the coldness of the material with the warmth of a human body. The romantic and crystalline undertone of these works responds to their impenetrability; they might be inhabited by a supernatural presence, a fluid substance that Lotarevich packs, welds, cuts, recomposes; she extracts humanity from the antihuman.

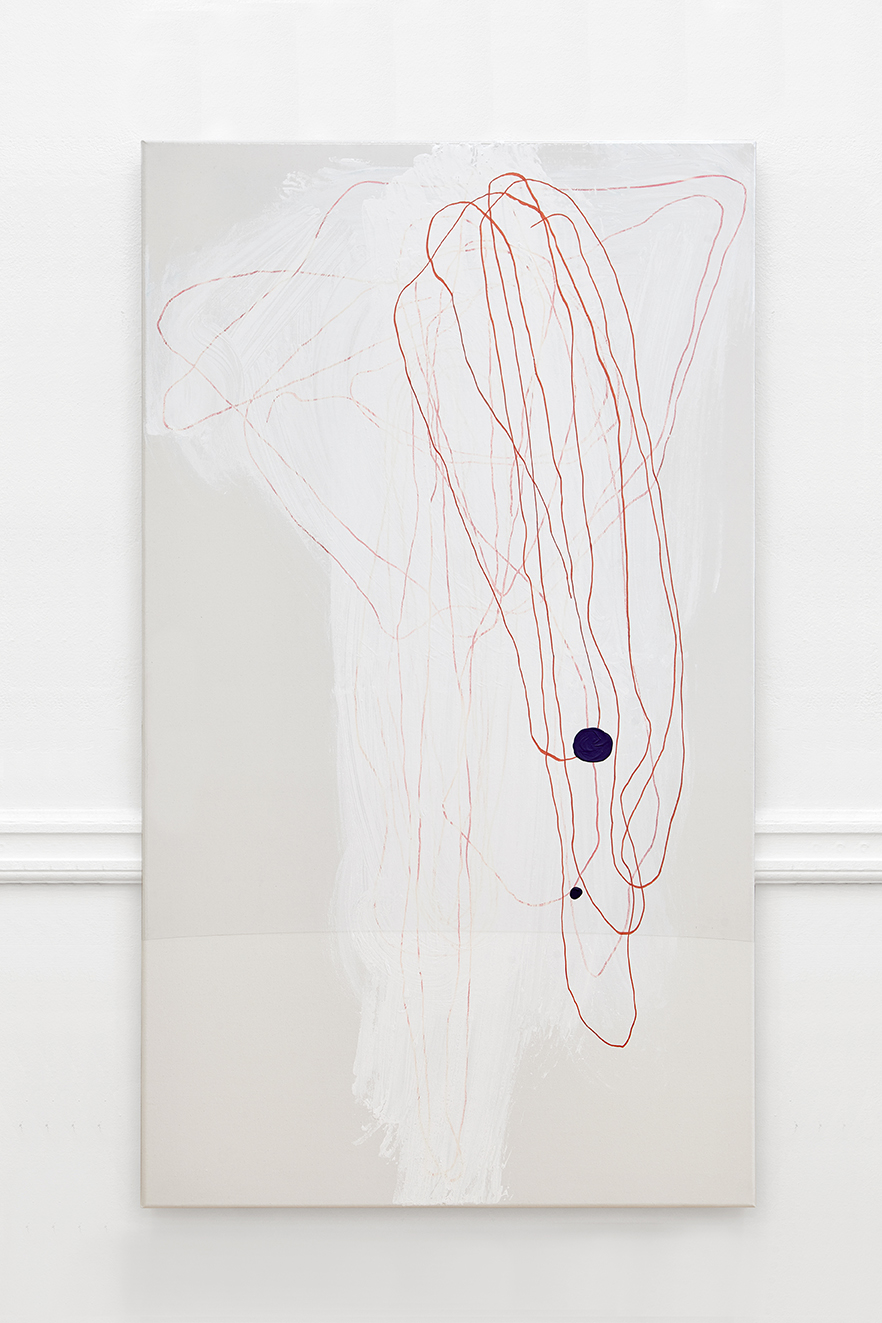

Jesper List Thomsen at Hot Wheels Athens

Of the countless ways in which an artist takes up painting, Jesper List Thomsen (b.1979, Denmark, based in London and Turin) follows that of words and performance. Two pictures are welcomed again on view at the Hot Wheels booth in Paris after accompanying a past List Thomsen radio piece in Athens. These works introduce a physicality that reminds of Tracy Emin’s works on canvas, a stripped expressionism that occasionally features text too. A recording of the artist reading a 4 second-long verse that simply says “FREEEee”, an excerpt from his namesake book we had the chance to get hold of at the Paris fair, powerfully echos the forms in qm3nvwv (2019), one of the paintings in the Hot Wheels booth; the voice pitches downward, yet the focal point of the sole performer remains steady. In the painting, a dot of paint seems to be running along curvy marks laid out vertically, suggesting an up and downward movement not dissimilar from that of the voice. Both words play with freedom, literally and metaphorically.

October 25, 2022