Kelly Tissot: altered spaces

Through photographs and sculptures, Kelly Tissot channels the spectres of life in what she terms “the abandon promise of the rural utopia”

Like Kelly Tissot (b. 1995 in Haute-Savoie FR, based in Basel), I grew up in a small French town, a place that has impregnated my own tissues, like it must have Tissot’s, with isolation and sadness, but also beauty and vastness. The violence evoked by her photographs and sculptures is familiar to me: the melancholy, the boredom and the illuminations of the suburbian non-spaces, those that drift through unmapped zones so silent that they look like they have been forgotten; I, too, have taken the long-distance rides along the humid fields, fear mixed with desire in the pitch black nights of these constellated lands.

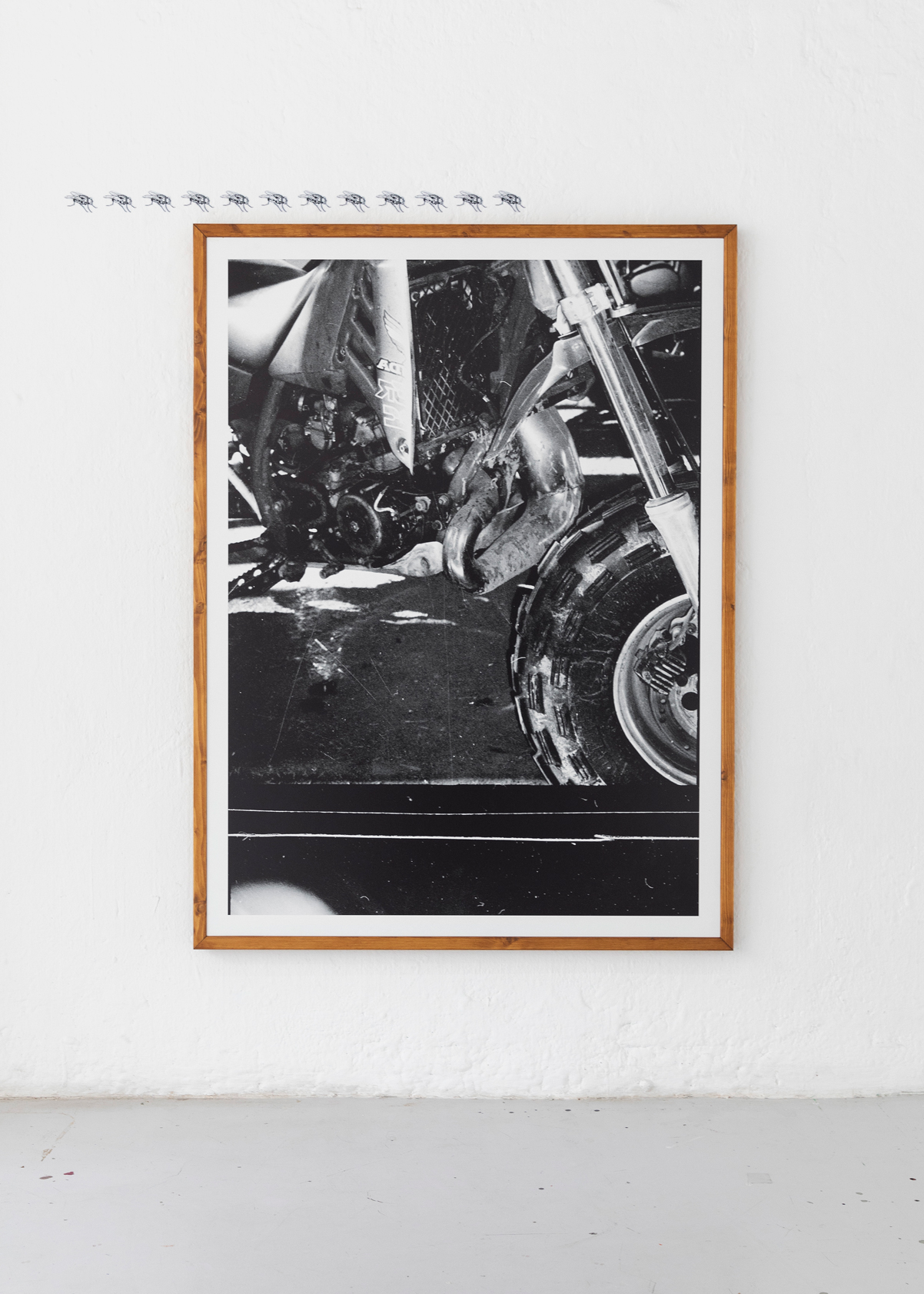

Looking at Fuel-soaked snooze, a series of photographs Tissot showed at Forde Art Space in Geneva and Kunst Raum Riehen in the Spring of 2022, one can feel the density, the depth, and weight of these rural shadows. The large black and white pictures depict motocross bikes from up close, lit with a flashlight, in what seems to be an abandoned barn. There is something austere, but also silent and sublime in the way these vertical prints are elegantly displayed at various distances from one another. Playing with the luminous voids within the white paint of the walls and the deep black unknown space of the photograph around the prominent engines, carburetors or wheels, Tissot lets the viewer explore what quietly lies between the objects. “They were just there,” she told me during a recent zoom conversation. “I opened the door and the machines were there, and I had this intuition immediately: it seemed obvious that I had to make a series of pictures of them.” There is also a certain neutrality in the way the pictures are taken, composed, and arranged. One might think of a photographic investigation, a visual exploration, the camera getting closer to the machines, recording the signs of something like a masculine, yet hidden, cult of speed and noise.

The verticality of the composition, the classic perfection of the wooden frames, the sensuality of the contrasted black and white prints suggest a magnification of the subject. “I have always aimed at working against the clichés of rural life to de-romanticize its landscape.” clarifies Tissot. Effectively, her photographs document a world that lies still, but remains menacing, potentially hostile. The motorbikes are like sleeping wild animals that could wake up any time.

This potential violence also manifests in her series of photographs Mute, mutt and deadspace (begun in 2020), in which destroyed machines and ruins dialogue with portraits of dogs staring at the camera. It is difficult to know whether the ambiguous images face us with the apocalypse from the near future or mere documentation of the margins of our time. There is a oneiric atmosphere–the fringe of the nightmare, one might say– in these works, which capture a reality on hold, suspended, waiting for something to happen. Printed on aluminum, this series creates a dynamic and destabilizing relationship with the viewer: Strangely, when one moves around the works, the reflection of the surface where the “whites” are printed, animates the image.

Like in Fuel-soaked snooze, the subjects in Mute, mutt and deadspace were shot from very close. They do not allow a global view on the situation, and immerse the viewer in a visual, almost tactile exploration of a broken, metallic universe. They are fragmented, (re)framed and cut, perceived by portions. At Forde in Geneva, as well as at Kunst Raum Riehen, the artist also presented a series of sculptures that were placed in the space in relation with the photographs. Simplified and abstracted from real life objects, they acted like dark guardrails obstructing the space, fragmenting perception. As architectural devices, they accentuated and incarnated in three dimensions the fragmented point of view suggested by the photographs. Some of the sculptures resembled a bench, a tier from which the upper part might have been cut and moved, impeaching its usage but acting like partitions in the space, barriers that constrained the movement of the visitors. The sculptures sometimes broke the perspective, partially masking the pictures like dark shapes blocking vision. Inspired by devices against the displacement of farm animals in fields, the sculptures were built by the artists according to the space and animated their mute presence for the body of the viewer. “I consider them as repressive structures, forms of control and objects that partly avoid participation,” said Tissot in our last exchange. “Like the machines in the pictures, they are extremely functional, but I make them feel as if they were waiting for something, as if they were in standby.”

Tissot’s last exhibition titled Spurious Crops at Kunsthaus Baselland features a new sculpture: a repetitive structure of steel beams on the floor suggesting both a skeletic bench and a cage. This massive, menacing piece is a direct and physical manifestation of control, of constraint even; it allows the visitor no full experience of it. This is an object with a mental dimension as well as formal, where shapes and materials tap into one’s feelings–what is it like to touch the metal, to be imprisoned in it? The works in Spurious Crops address ways of separation: the physical break suggested by the sculpture/cage/bench; the gallery’s cuts through architectural partitions (Coating against nostalgia/Cobalt glints I, II and III).

A new series of photographs – scarecrows this time – entitled Dubious portrait and improper meeting tie the show together. In them, Tissot evokes a specific place in France’s Haute Savoie region she knows well: a theme park dedicated to scarecrows created by locals. The dummies seem to be existing between realms, human, non-human, real, fictional and existence makes it a haunting place, reminiscent of the menacing dark forces of Southern Gothic taste described by William Faulkner, where the tension is as invisible and spectral as it is cinematic. The artist says: “The scarecrows interest me, as I want to reveal the duplicity of the rural idyll in my photographs and sculptures.” She made a series of “portraits” of these dramatic characters, taken from very close. The result is again a fractured picture, showing torn up clothes and patched up faces, half-objects, half-humans, half-funny personas, half-scary monsters. These are forms of unclear nature, decomposed and recomposed, made out of remains and ruins; they are melancholic collages of collages, fragments of fragments. “I am interested in ideas of isolation, attachment and resignation,” Tissot mentions. The precarity of the subjects–fragile humans made out of leftovers and rubbish–is reinforced through the leather surfaces on which the photographs are printed before being mounted on canvas. Her process also works as patching, from the framing of the pictures to the montage onto structures supporting the prints; it connects everchanging compositions to the very ideas of tinkering and repair, making the scarecrow not only scary, but also vulnerable and composite.

Tissot patiently and silently observes what she terms “the abandoned promise of the rural utopia.” In Dubious portrait and improper meeting, the scarecrows are photographed from so close that their images become landscapes. The torn collages of fragmented pieces of fabric that act as clothes for the scarecrows open up some kind of map before our eyes. In The mushroom at the end of the world, Anna Tsing reflects on how the fragile forms of life and our precarious environments are structured through “patches”, a series of homogeneous spaces that differ from what lies around them. For Tsing, life is ultimately based on a mosaic of open and entangled arrangements of forms and processes, themselves composed of other complex “tapestries” of diverse rhythms, temporalities, spaces, and scales. Behind the daily and the unimportant, Tissot tracks the hidden structures and animated things, the loaded signs that lie under the material landscape. Her works, like mute phantoms or silent visions, shed bursts of light – flashes of darkness – onto the contradictory and wrecked dimension of a divided culture, connecting us with the invisible affects so we can face a damaged world.

November 23, 2022