Pretty hurts: the skinny legends of David Rappeneau

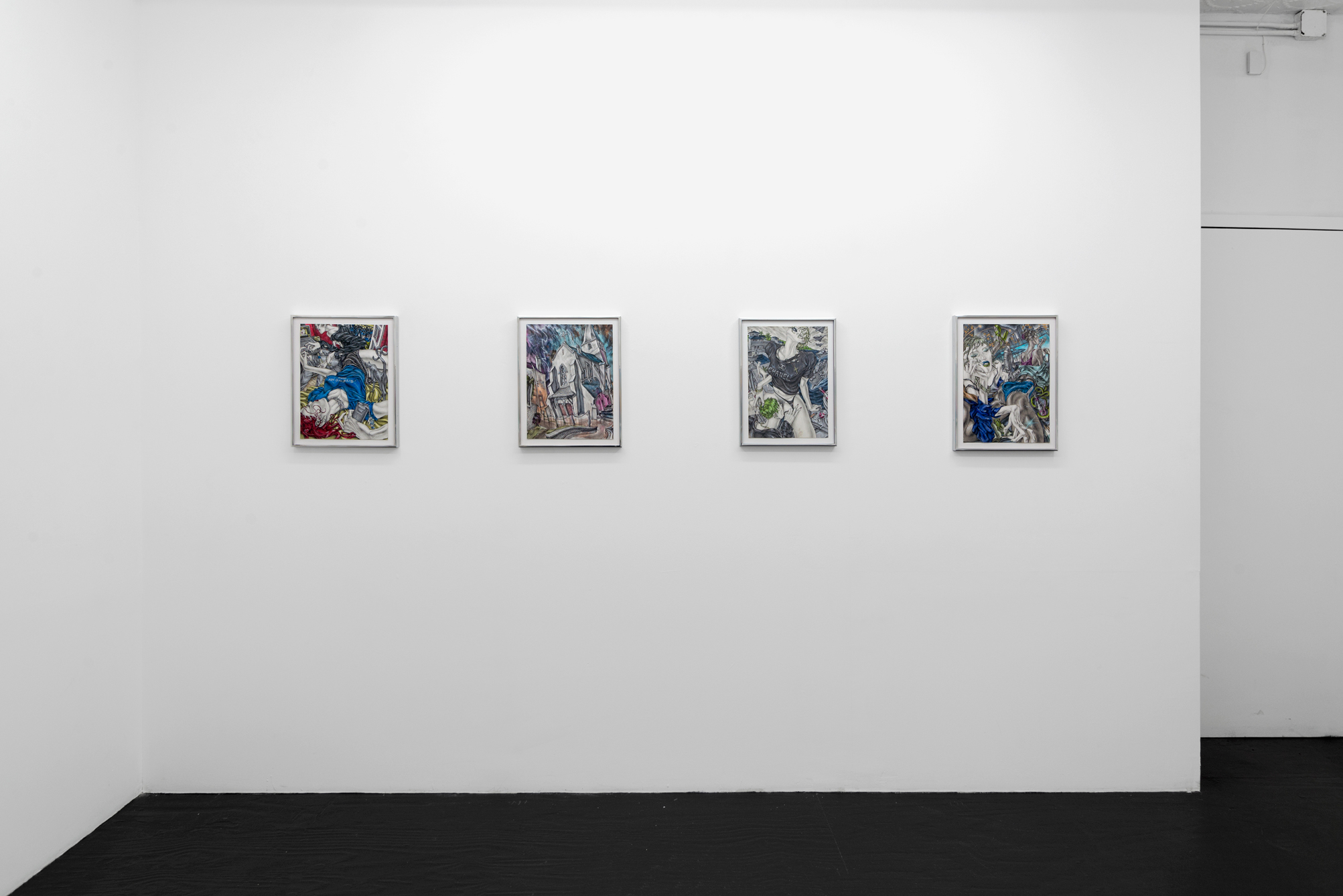

The storytelling technique of David Rappeneau is realism brushed with the fantastic. His neo-libertines seduce the communally divine

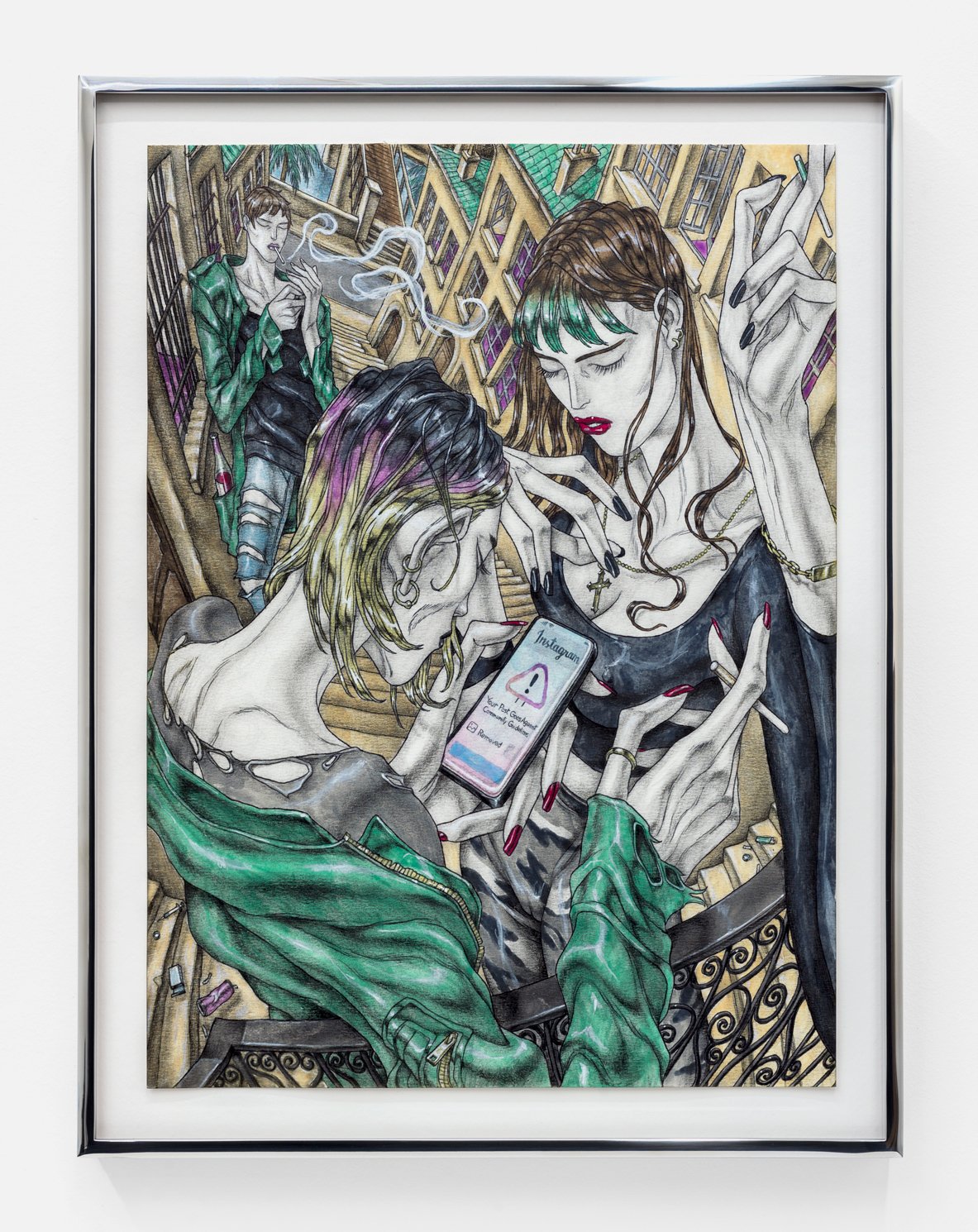

People fool around and feel it out. This happens often in the drawings of David Rappeneau, which are full of funny people – ingénues, entrepreneurs, and daydreamers – as skinny legends. They come in duos or trios and, recently, are outlined by a ballpoint pen. Their skin, clothes, and surroundings are rendered in a shuffle of acrylic, pencil, charcoal, and marker on paper. The skinny legends slither into their smudged surroundings, close cousins to Mel Odom’s airbrushed cuties and Sybil Lamb’s scrawny city slickers.

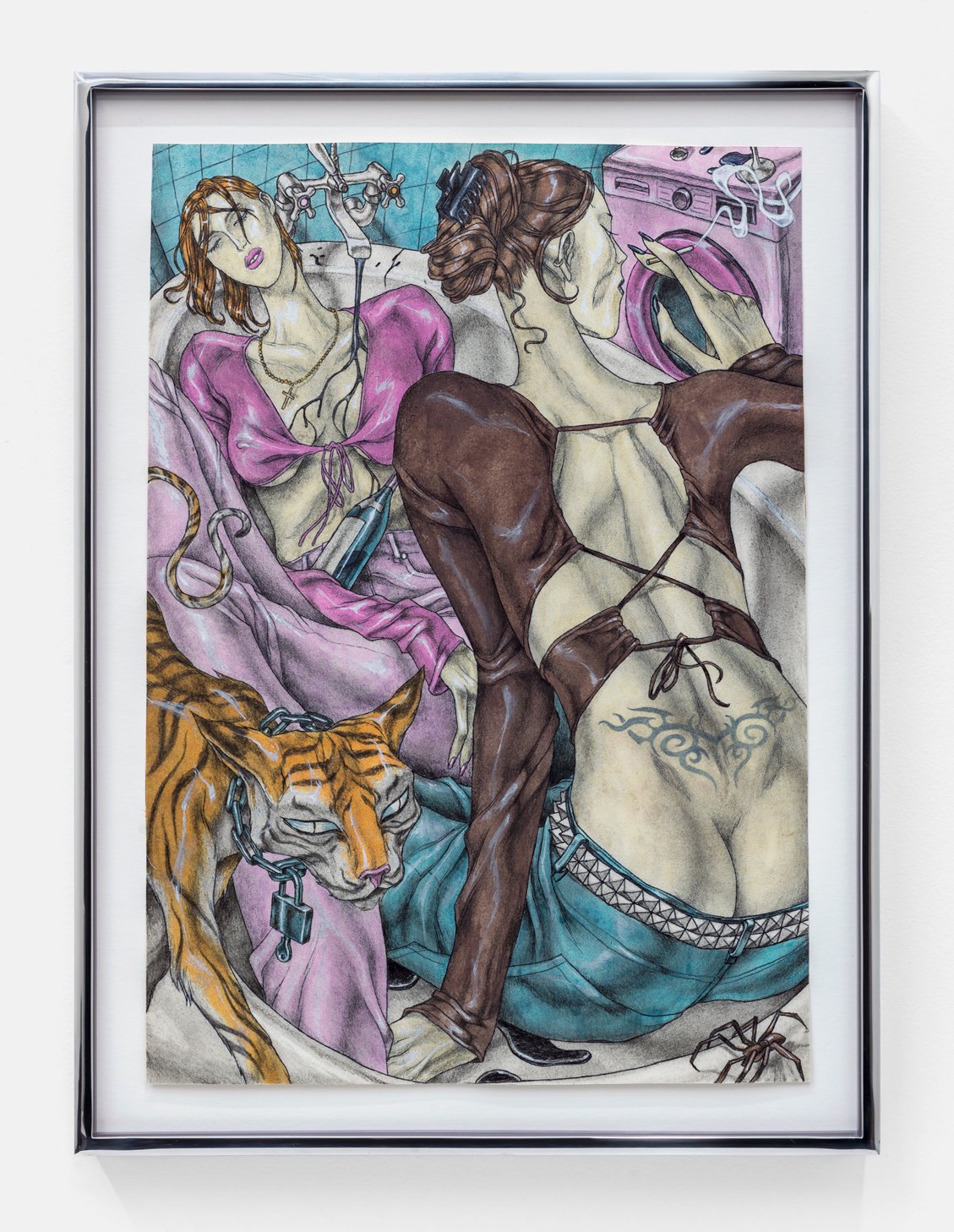

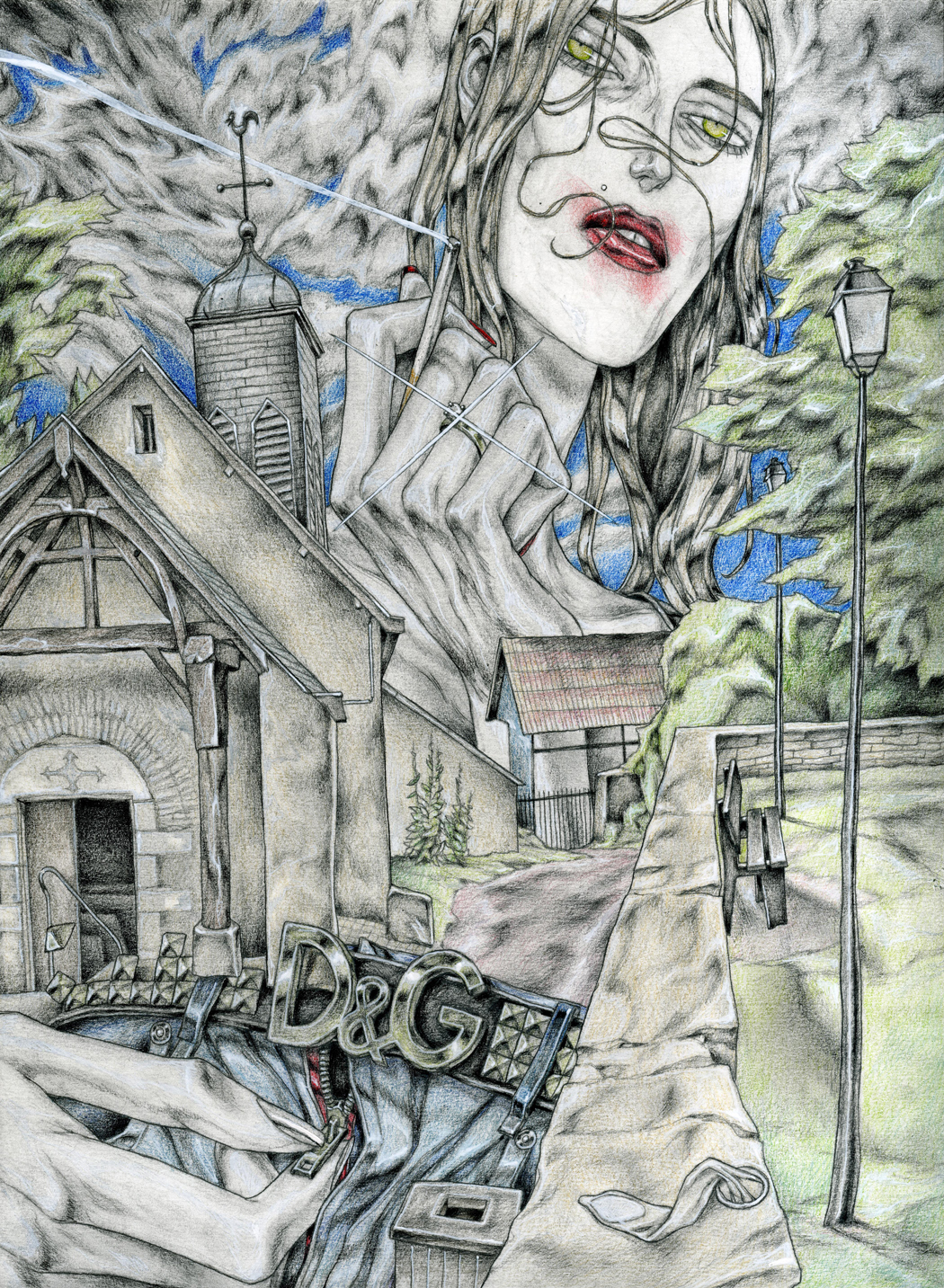

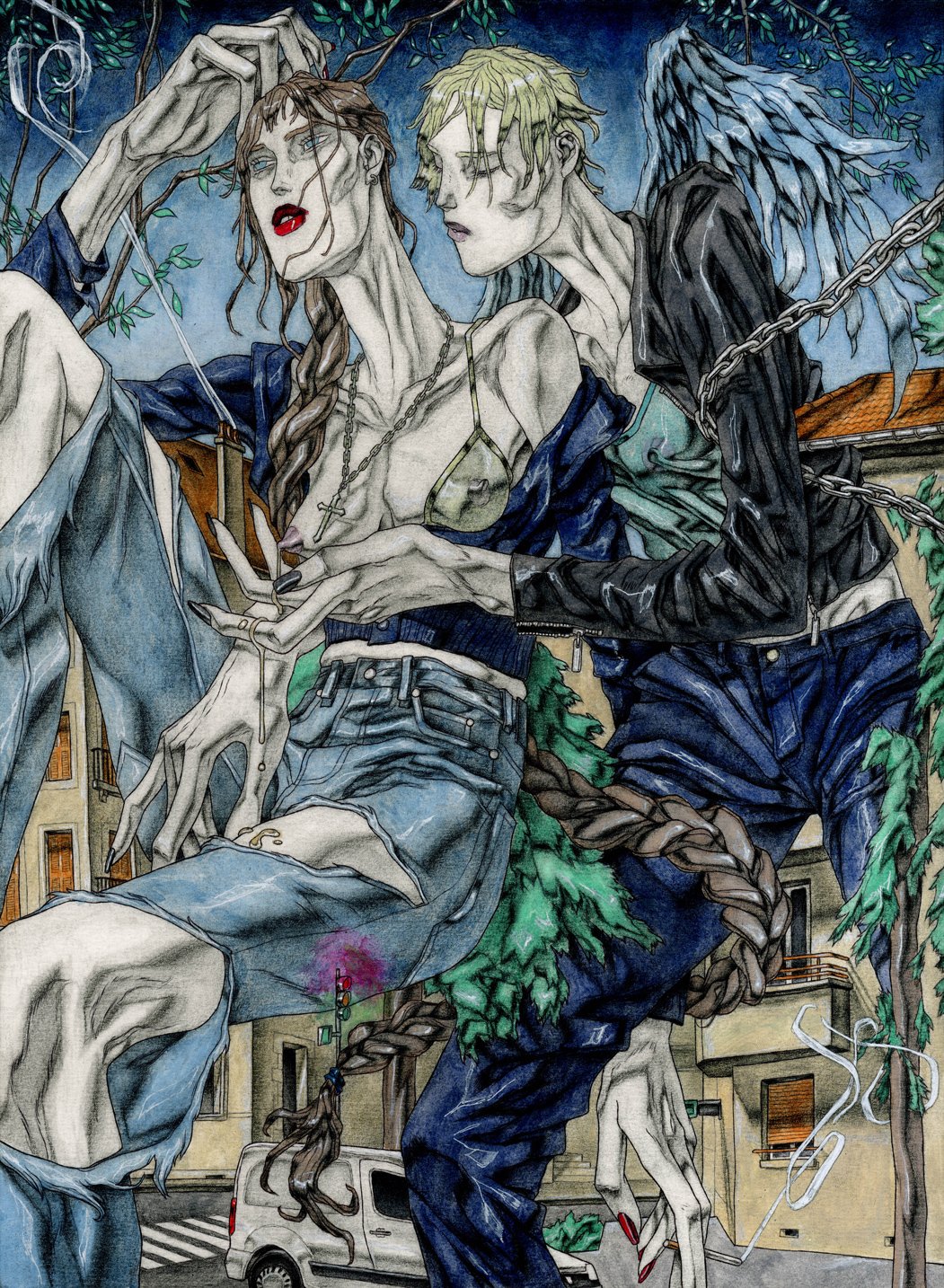

Rappeneau’s figures often look like they might fall out of the picture plane, twisted smoke crimping into a ribbon around them, mimicking their Cirque du Soleil freakish contortions. The smoke’s swirls draw one’s eyes to nearby spirals: a flyaway sterling silver necklace, a backless crop top’s knotted strings, or curls appreciating a breeze.

The artist’s guys and dolls share a uniform of slutty city suits, threading his figures back into tight social scenes. Cut muscles and skeletal protrusions meld into famous designer brands. In Untitled, 2022, a woman wears a Givenchy t-shirt and brown mini-skirt. The combo wrinkles wildly over her shiny skin. In another work, two babes wear Balenciaga tracksuit jackets that slide off their shoulders as if folded-up putta wings, while Mugler booty shorts congeal into their groins. The artist serves up some pretty juicy couture.

For his 2022 solo show at Queer Thoughts in New York titled “Mirage 2000″, the works, all untitled, all 2021 and 2022, chronicled fashionista languor. Figures lounged on fire escapes or on rooftops in work that gave the appearance of being outdoors. One spied beloved landmarks from London, Paris, maybe Tokyo. Further off in the distance were the titular fighter jets (hot commodities for some of the world’s worst arm’s dealers), orange missiles, and mushroom clouds. War has broken out in these overcast skies: The misfits hide on top of wrinkled bed sheets or under blotchy skies. They might be displaying a rebellious streak of streamlined incuriosity, too, while looking nonplussed as viewers pointed at them in the gallery. “S/he reminds me of that friend,” “this one a lover,” or “that one, our other.”

The blotchy backgrounds felt familiar. They were like tear-streaked eyeliner or facial bruises after botox. Pretty hurts, you know? With backdrops like these, Rappeneau might be making a statement about how unflatteringly self-important it is to believe a city’s history and greatness will brush off on you by sheer proximity. One should be more courageous—how to survive the city and its crumbling walls otherwise? Restrain the groans: History, even greatness, is nearby, just dressed up as the future waiting for you to eat her up.

Other Rappeneau scenes redeemed the definition of the indoors, depicting cramped interior bedrooms or bathrooms: a laptop plays erotica; a pink washing machine itches to be turned on; and a fag, a third, is enjoyed by lovers; close by, a pussy cat saunters on over, excited for incoming rain showers. (Showers coming, of course, if they participate in this little rendezvous.)

In Rappeneau’s world, all living beings move towards pleasure. Burning desire abounds. Yet there is unease in the air, a late-capitalist désabusement. There’s a feeling that at any moment everything might fall off the table and get swept under. Who, or what, will be their savior during these secular times? Surely not their maker, who shows almost-stable tableaus of pleasure, eclipsed, rather inconveniently, by a dwindling chink of denial: the fearful feeling that one’s infrastructure – or, internal logic – could collapse if one takes a leap forward.

“Sex,” or any contact that touches on the untamed social, “complicates the ordinary, because, even when it isn’t collaborative,” writes the late Lauren Berlant, “it forces the rational/critical subject to become disorganized for a bit.”[1] It is no wonder the artist’s figures cast longing looks. People always seem to know what they don’t know. Denial precedes pleasure, and, once pleasure is set into motion – rolling, growing, groaning – denial lingers. While this contradiction is disorganizing, its power is really seductive. Sex works because sex sells a way of life. And, there are many ways to live.

For the artist, pleasure is much less a quest of self-discovery than it is a leap, a flight, of self-invention. In his vision, pleasure is something in which one can invent new ways, new shapes for cohabiting. In one work, a dark-skinned figure with braided turquoise hair perches groin-to-groin on top of a boy nymph. The top rider, with khaki-green legs bent backwards and arms outstretched on either side, is prepared to lift off to greater heights. The bottom lover grips their bum should the love on top fail to fly. The skinny legends, with their faux-fashion wings and beauty marks, are right to let go and let beauty grow.

Figures with actual feathered wings were drawn and shown during the COVID-19 pandemic. These winged demi-gods appeared online, on the artist’s cult-following Instagram and Tumblr pages, and at Gladstone Gallery with a solo exhibition titled “†††††††††††††††††††††††††††” that opened in Brussels in 2021. All of his winged figures have forlorn expressions and are in need of some comforting. The text for the show, written by Charlie Fox, offered similar sentiments. In one work, Fox writes, “The angel sheltering a sick boy in his wings by starlight looks depressive, too, chained by who knows what earthly sorrow: Melancholia I for the time of Xanax.” One has a hard time believing these are images of anesthesiologists addressing spiritual wounds. Something else is going on. Perhaps angels offering corporeal accommodation during a regular check-in with their beautiful mortals.

The skinny legends are beautiful. They are beautiful beings for what their body contact represents — a network of neo-libertines. They spawn camaraderie, forge new alliances while obliterating soul-crushing alienation. Together in bed or by a bay window, they throw away, “a labyrinthine wardrobe of tortured interiority, self-involvement,” [2] as the late historian Christopher Chitty has noted of the histories of so many, well, historians. The artist’s own history is, for the most part, completely unknown. No interviews, no press photos, not even a Wikipedia page. Does he even exist? Here is what we do know: he is French; he is an artist; he is living, and, apparently, working in France. All fine. Fortunately, art and history can be relational, comparative.

Rappeneau’s technique of storytelling is realism brushed with the fantastic. Each neo-libertine seduces the communally divine, enabling the following in one another: surprise (“Your Post Goes Against Community Guidelines”), naivety and the shame of difference (a cat poking its nose under a woman’s skirt, purr), weakness (three works from “Mirage 2000” were drawn from the first-person perspective of a bicyclist on a tiresome journey to a church, redeeming the definition of the outdoors), theories of positive positionalities (one could argue taking a smoke break encourages a brief moment of deep breath and reflection), and protection (collective action, teamwork, peer pressure, safety in numbers, etc).

What else are his figures to do now that the pandemicene floodgates have opened, protests now rarely spoken of? Rather than cry about faded pleasures, they are just like us: left to their electronic devices.

[1] Halley, Janet E., Andrew Parker, and Lauren Berlant. “Starved.” Essay. After Sex?: On Writing since Queer Theory, 79–80. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

[2] Christopher Chitty, Sexual Hegemony, 165, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020).

December 12, 2022