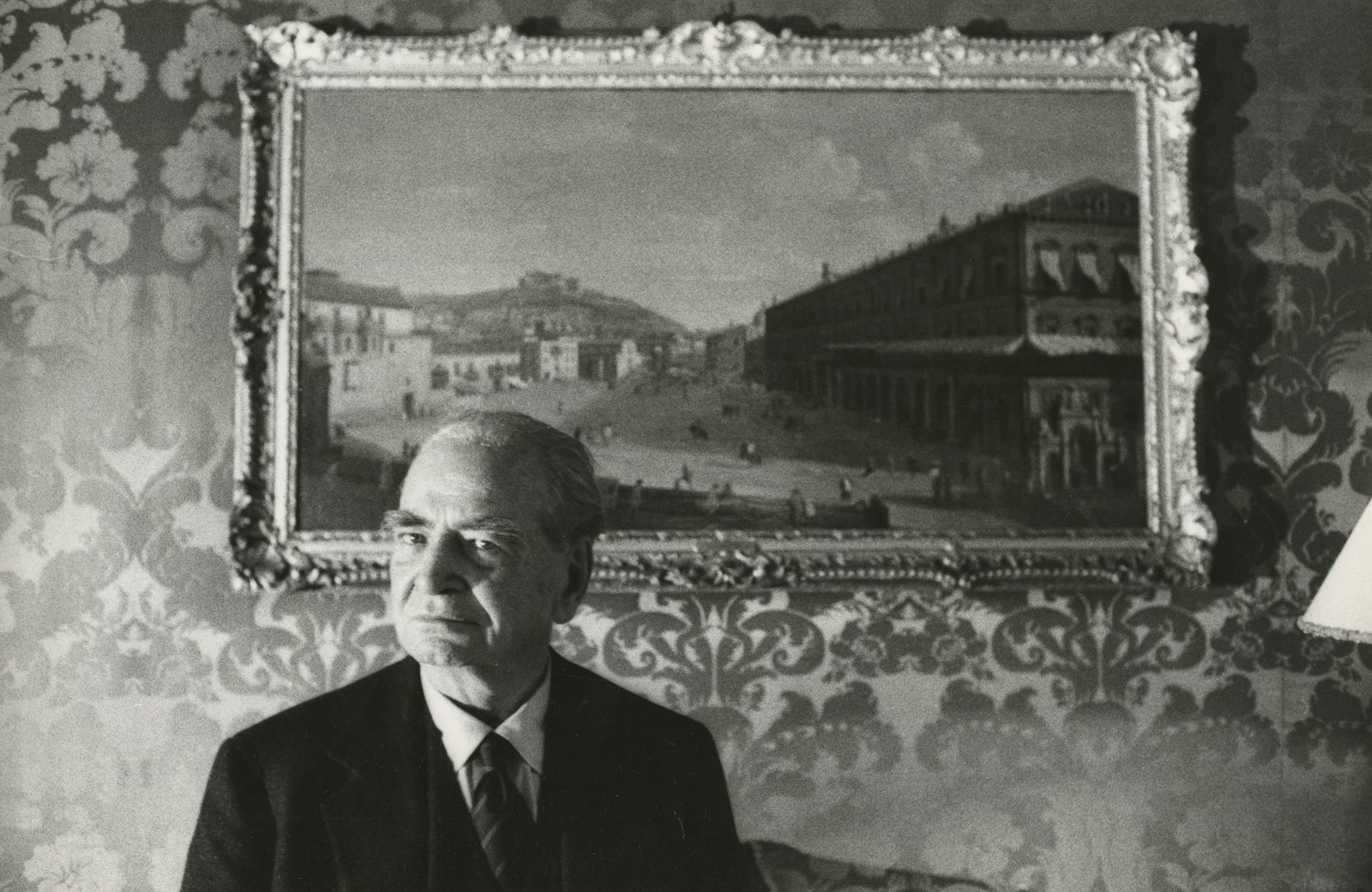

Raffaele Mattioli, a patron of humanist culture

An exhibition at the Gallerie d’Italia explores the collecting of the great bankers, from the Medici to the Rothschilds, via Raffaele Mattioli

“[Raffaele Mattioli] reminded me of one of those timeless old men who live in Michelangelo’s frescoes. I realized that I was in the presence of a Renaissance patron who was temporarily loaned to the twentieth century.”

– Joseph Wechsberg

“For he was not a patron of the arts because of a compensation he might seek; he instead spurred research, knowledge, and art’s freedom from any form of servility,” wrote Giulio Einaudi in 1975, commemorating the great Italian mecenate Raffaele Mattioli, grasping the distinctive traits of his banker friend’s approach to culture. For Mattioli, art patronage was a civil commitment to contribute in the greatest way to the development of a country. As an expression of culture in a broad sense, like literature and music, he appreciated art not only formally but also, and above all, for the values and content it represented, as a testimony of the world that had produced it. Within his philosophy, art was a means to dialogue with artists – the greats of the past even – and to make their teaching his own; it was a means to “see how one is, where one is, and where one is going.” In this regard, for him an artwork transcended its material value.

Mattioli’s view on art made him less of a collector than a sponsor: He was uninterested in the exclusive physical possession of a piece, rather assuming the role of the scholar, the connoisseur who works for the protection, knowledge and promotion of the arts. His principles were most clear when it came to literature and theory; he was active as a publisher after the acquisition of the Riccardo Ricciardi publishing house in 1938, which boasted a great quality catalog and offered a platform to young and promising scholars to take their first steps in public. His desire for knowledge was limitless, often resulting in donations and enrichments of public and university libraries.

The Raffaele Mattioli circle and the nights in via Bigli

From his move to Milan in 1920, at the time of his experience at the “Rivista Bancaria” magazine, at Bocconi University, and at the Chamber of Commerce, before being hired by Banca Commerciale Italiana in 1925, Raffaele Mattioli frequented intellectuals and scholars of different orientations and origins, including some of the art world’s young local members. This became his small but diverse bohemian entourage, which included Gigiotti Zanini, a painter and architect from Trento who distinguished himself for landscapes with primitivist traits; the art critic and writer, as well as painter, Benso Becca; the gallerist Enrico Somaré, founder of the periodical “L’Esame. Rivista mensile di Cultura e d’Arte”, where famous artists like Ardengo Soffici and Carlo Carrà published. The group also included the architect and urban planner Giuseppe de Finetti, one of the most interesting and singular ones in the first half of the Italian 20th century, active in the “club degli urbanisti” in opposition to the dominant taste of the Fascist regime. More secluded in the group was the engraver, painter and writer Anselmo Bucci, one of the founders of the Novecento group, and the painter and set designer Mario Vellani Marchi, a pupil of Pio Semeghini and friend of the writer Riccardo Bacchelli, in turn one of Mattioli’s closest friends. Sergio Solmi, Mattioli’s collaborator in the legal service at the Banca Commerciale Italiana (of which he’d become the director) kicked off his career as an art and literary critic in connection with this scene.

The Mattioli circle, sometimes referred to as his “last supper” met occasionally during the so-called “nights in via Bigli:” the friendly gatherings at his house, one of the few hideouts for free thought during the Fascist regime in the country. It was thanks to these meetings of passionate speakers of various kinds that Mattioli made contact and committed to art and culture: He stimulated his friends’ activity, as well as guaranteeing their livelihoods through commissions often linked to the Banca Commerciale Italiana. (He had become managing director of the large institution by 1936, a position he’d hold until 1960 before becoming its president until 1972.) For example, he entrusted de Finetti and Zanini with the renovation of various bank buildings in the 1930s, including the headquarters of the central management in Piazza Scala in Milan, as well as his own apartment on Via Bigli 11. He also bought some of Zanini and Bucci’s works, also involving the latter in artistic jobs connected to the publications he initiated.

Guttuso, Morandi, Manzù

Raffaele Mattioli’s circle expanded further after the end of World War II. Through mutual friendships, he came into contact with some of the greatest exponents of the Italian visual arts of the second half of the twentieth century: Renato Guttuso, Giacomo Manzù, and Giorgio Morandi. Although already established or in the process of becoming so, the banker was still able to stimulate these artists, providing moral and material support when they needed it. For example, he introduced Guttuso and Manzù to new clients or gave them new commissions in the context of his bank, while actively buying Morandi’s works for his own collection.

Although these three artists stood out – a famous newspaper wrote in the obituary of Mattioli that “many of the most illustrious names in the Italian figurative arts blossomed in the shadow of this great patron” – by no means Mattioli’s circle was limited to big names. The lesser known were integral part of the scene he helped build.

A look between present and past

Although being rather unfamiliar with new artistic currents at the time, in the 1960s Mattioli endorsed the project of Vittorio Corna, the head of personnel and of the bank’s art department, to enrich the bank’s collection with recent works by Italian artists from the 1950s onwards. In recent decades, this has become one of the identifying parts of the Banca Commerciale Italiana’s involvement in art. Alongside the contemporary, Mattioli also sponsored the protection and study of ancient art, which he deemed indispensable for the identity of the country and of its society: “To preserve Italy, to preserve the classics and monuments, to preserve the tradition; to be a man of tradition and an innovator at once,” summarizes Piero Treves. Thus, throughout his life, the banker worked to save Italian artistic heritage, making sure it would be accessible to the public at large in the museums and institutions he supported. In an essay dedicated to Mattioli for his seventy-fifth birthday, art historian Roberto Longhi wrote that “artworks belong to everyone, they are the common good of the citizens of the whole world.” The museums that keep them should be “alive and growing.”

A work in its context

Raffaele Mattioli also ensured that artworks were not eradicated from the places to which they belonged and those that had been already could be returned. It was a fundamental principle for him: A work was born in a context, it related to it, becoming one of its inseparable parts. Already in 1937 the Banca Commerciale Italiana under the leadership of Mattioli donated the Adoration of the Magi by Gaetano Previati to the Pinacoteca di Brera on the proposal of the then president Ettore Conti, who was also head of the Association of Friends of Brera. However, the most emblematic and well-known case of Mattioli’s approach to keeping Italian heritage in Italy remains that of Michelangelo’s Pietà Rondanini: in 1952 the banker discreetly helped the Municipality of Milan with the necessary funds to acquire the work – today it is preserved at the Castello Sforzesco in Milan – against the sale to an American buyer.

There are many similar episodes of sponsorship attributable to the banker from every corner of Italy. Also in Milan, Mattioli managed to get the painting Christ Enthroned Adored by the Angels by Giovanni da Milano to the Pinacoteca di Brera in 1970, taken over with “decisive interest” from Count Alessandro Augusto Contini-Bonacossi who previously owned it. He also paid particular attention to the heritage of the city of Naples, to which he was emotionally linked: Evidence of this love is the gift in 1959 to the Gallery of the Capodimonte Museum of the bronze by Vincenzo Gemito, Neapolitan girl, which the Banca Commerciale owned from 1956.

On other occasions, Mattioli made sure a few ancient masterpieces would remain in Italy by acquiring them for the bank’s collection. Among them is Portrait of Fattori by Giovanni Boldini from the Gualino collection, and Largo di Palazzo in Naples by the Dutch painter Gaspar van Wittel. Subject of careful research by Mattioli, once identified and purchased on behalf of the bank, he kept the van Wittel picture in his office in Rome but not before expanding the scholarly research on it with a commissioned new study by art historian Gino Doria.

Mattioli’s interest in artistic heritage also took the form of sponsorship of large scientific and archival efforts, as well as indirectly advocating for art historical studies in general: In the 1970s he promoted the extensive mapping of monuments in Milan, of which no complete picture existed yet. To put it as Leo Valiani, the banker supported the “erudition that gives concrete corpulence to [heritage].”

Relationship with scholars

Mattioli was in conversation with art critics and scholars for most of his life, keeping good contacts with great figures such as Bernard Berenson, Lionello Venturi, Roberto Longhi, Paola Barocchi, and Lamberto Vitali. For them he was “always a solicitous advocate of our most serious cultural needs,” in the words of Longhi himself. He commissioned Venturi to write the essay on the art history in the book Cinquant’anni di vita politica italiana 1896-1946, the final report on Italian studies of the previous fifty years, edited by Mattioli and Carlo Antoni for the eightieth birthday of Benedetto Croce. He backed the Italian translation and publication in 1961 of Berenson’s fundamental work The drawings of Florentine Painters with Electa publishing house, as well as perpetuating the memory of the critic with the publication of the Italian edition of other Berenson works through his own publishing house Riccardo Ricciardi; these included a biography by Sylvia Sprigge. By virtue of his historical sensitivity and his philological attention, he involved Paola Barocchi in the Ricciardi publishing house, for which the scholar edited in 1962 the powerful work by Giorgio Vasari The life of Michelangelo in the editions of 1550 and 1568 (published in the series “Documents of Philology”) and subsequently, at the beginning of the 1970s, for “La Letteratura Italiana. Storia e Testi. Scritti d’arte del Cinquecento,” the second volume, which saw the light precisely in the year of the banker’s death.

Among the last acts of his life, with a farsighted gaze, Raffaele Mattioli thought of ensuring the new recruits for his beloved research with the establishment of a specialized high school, the Fondazione di Studi di Storia dell’Arte Roberto Longhi, whose birth was envisioned with Longhi himself. Once the latter disappeared, Mattioli made sure that the project could be implemented and so, under his presidency and with the solid help of the scholar’s library and photo archive, the new generation of art historians could be born.

Note of the author: I thank Francesca Gaido for her fundamental research support and Gianni Antonini for the generosity with which he shared his personal memories, helping me to answer the many questions that archival sources were unable to answer.

Editor’s note: the Italian version of this essay was originally published in the catalogue of the exhibition “Dai Medici ai Rothschild. Mecenati, collezionisti, filantropi”, at Gallerie d’Italia, Milano, from 18th November 2022 until 26th March 2023.

January 18, 2023