It’s dark but just a frame: the drawings of Kyung-Me

Who and what exactly appears in the drawings of New York-based artist Kyung-Me, one asks, getting lost in their rich darkness

She waited, the artist Kyung-Me, for someone to make an appearance. But this someone had her wait unreasonably, and there were times at which she saw herself in the glass that encased her ink and charcoal drawings, a face absolutely warmed with the mollification that she would not catch sight of this special someone: absent as a figure, formless and carefree, and if pressed for coherence or need for meaning, consistency even, the figure would fully disappear from her line of sight.

All this looping from a rippled reflection. Go figure. The mind does awful crap while waiting around. We let it linger on incomplete projects, unresolved problems, fixed stories full of fluid figures. A story’s plot is easier to remember than its resolution and peace, even if we like it when things come together.

Kyung-Me starts out like most storytellers do: she blinks, readies her hand, and makes some choice other than a capitulation. To do this, she takes whatever black stuff – ink, graphite, or charcoal – she has nearby and presses it into Arches paper. She then follows a rhythm of three, diagramming a void, the dress it wears, and the decoration around it. Object, subject, fragment: dear unreliable narrator, please consider revising.

For the artist’s 2022 show Sister at Bureau gallery in New York, two parallel scenes of kindred-spirited sisters unfold in four stages, each itching towards omnipotence by the rhythm of three. In one story, four drawings (The Prostration, The Marriage, The Confession, and The Organ) follow the path of a nun making her way towards mother through a Gothic Revival monastery. These scenes capture deep set vistas with streams of stubby velvet curtains strung across cascading ribbed vaults and thick wood beams. Light flutters in strange diagonals through gilded stained glass windows in The Organ, where the hallowed instrument is joined with a frightening “M-m-mommmm?”

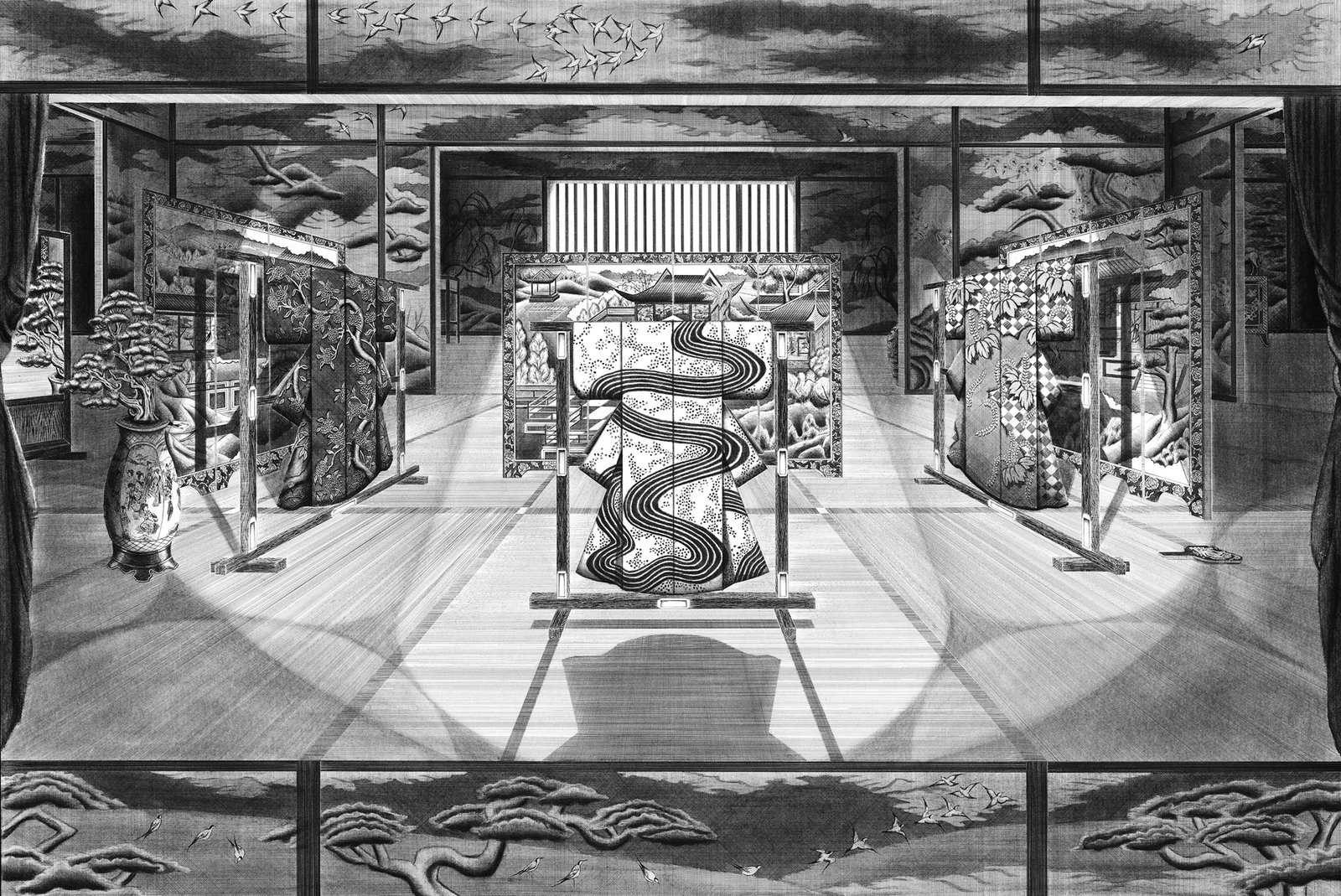

Four more drawings show the nun’s sister-in-searching: the story of a geisha, as Kyung-Me tells, “aspires towards another pristine image of beauty.” The geisha wanders deeper and deeper into the center of an okiya (The Resurrection, The Mother, The Profession, and The Vessel). Passing a kimono, a tea kettle, a sword, and a bridge, one begins to wonder, too, where is the house mother? Eventually, she finds mom and more. Each family of drawings follows a nesting doll parade of three: a daughter swallowed by her mother and her mother devoured by her house. To see the whole story is to see the hole that is at the end of every story: empty, inexhaustible, and birthing multiple worlds.

Multiple worlds, indeed. Changing times call for a change in rhythm. Like in OutKast’s “Hey Ya!” and Igor Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring,” Kyung-Me plays with deceptive cadence. Other time signatures in the artist’s repertoire include two-by-four (symmetry, duplicity, bisectionality, well, that’s two-by-three) and fear-induced four-by-four (fight, flight, freeze, and fawn). In Sister, each drawing is bisected by a vertical center axis. If cut in two, all of them achieve near symmetry, and are perfect lovers with their somewhat offbeat mise-en-abyme structure.

A story always has unfinished business. That might be the reason why we keep on telling them. There’s always more to tell. Even after we’ve seen the whole, and find ourselves at that story hole, we wonder, what happens next? It’s bewildering; the price we pay for gaining mastery in the art of substitution – telling through storytelling – is this sense of bewilderment.

In the final frame of Kyung-Me’s depictions of a nun and a geisha in-transit towards omnipotence, titled The Fall and The Gate respectively, each woman embraces a threshold of outer peace, karma, plain casualty: organized abandonment goes by any one of these names. (I like to think of it as something like sisterhood sticks.) Both sisters leap out of the frame and away from their predestined fate. Here, the frame falls out of focus, beyond their line of sight.

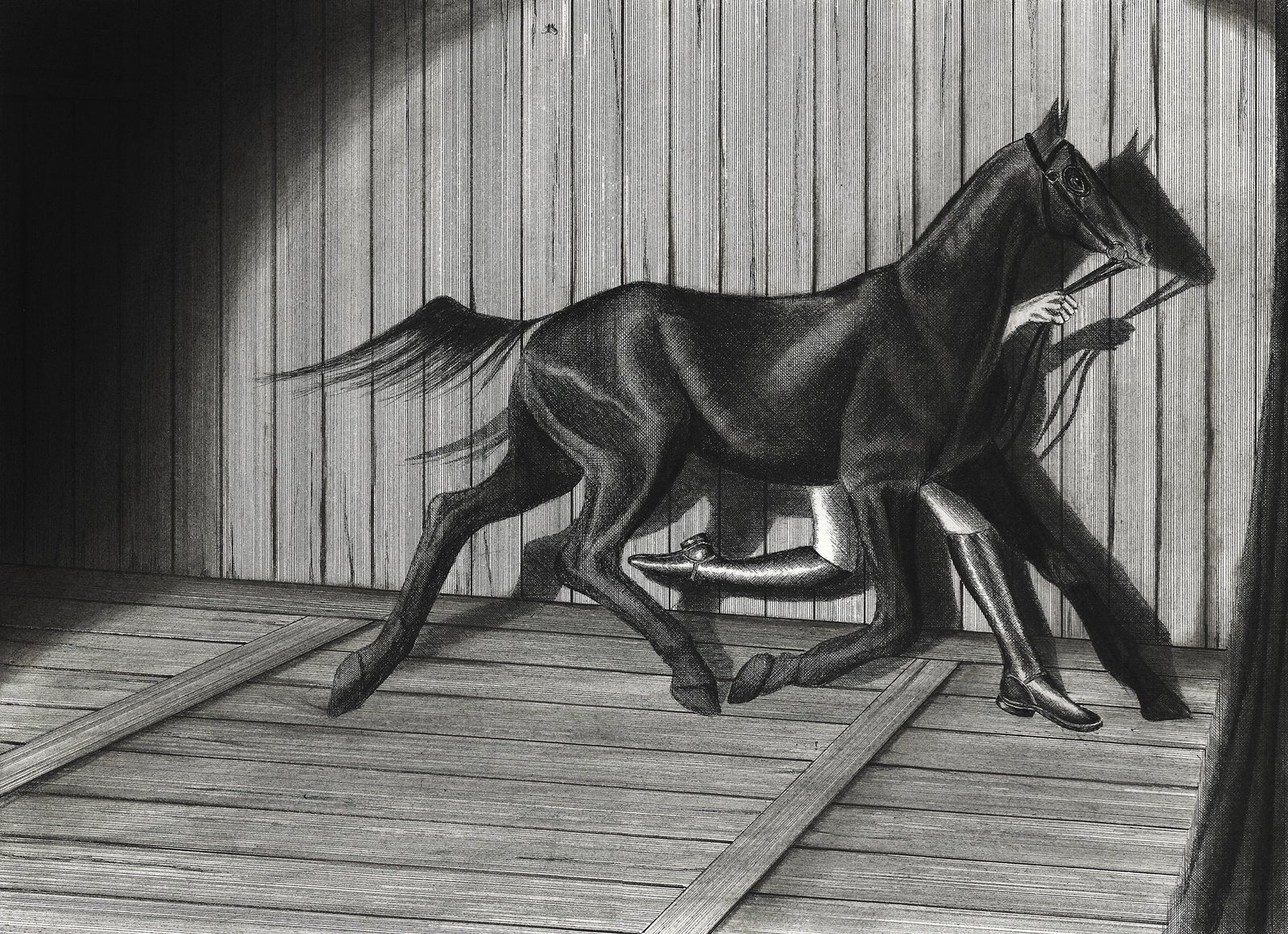

Perfect lovers make another appearance in Kyung-Me’s work. A few years ago, she drew scenes of piecemeal erotic error. Titled a boy and a horse, all 2020, the paper drawings show a slender youth adorned in slick riding boots. The family of five drawings portrays the story of the youth befriending a dark stallion. Handsome and loyal, the boy falls fast for his horse. It’s a sophisticated spin-off of Peter Shaffer’s play, Equus.

Here is another story about omnipotence run amok. In one drawing, the boy struggles on tippy toes to rest his head on top of the stallion’s back, and in another, he pets the stallion’s waxy coat. His curved, free hand resembles a freakish talon, useful should one need to catch something trotting away. The stallion ignores the boy’s uncoordinated body language and gazes out of a window. The window shows a bright, blinding void.

In a third drawing, the two gallop together and in a fourth, the boy’s claws grab the horse’s neck and bring its head through a pitch-black window, brought into darkness for either a violent kiss or, as the story of Equus goes, a spike to the horse’s eyes. It’s a carefully constructed scene of transition for the now-blind stallion living out a nightmare. A fifth, and final, drawing reframes the lovers as a domesticated union: a lone ponyboy.

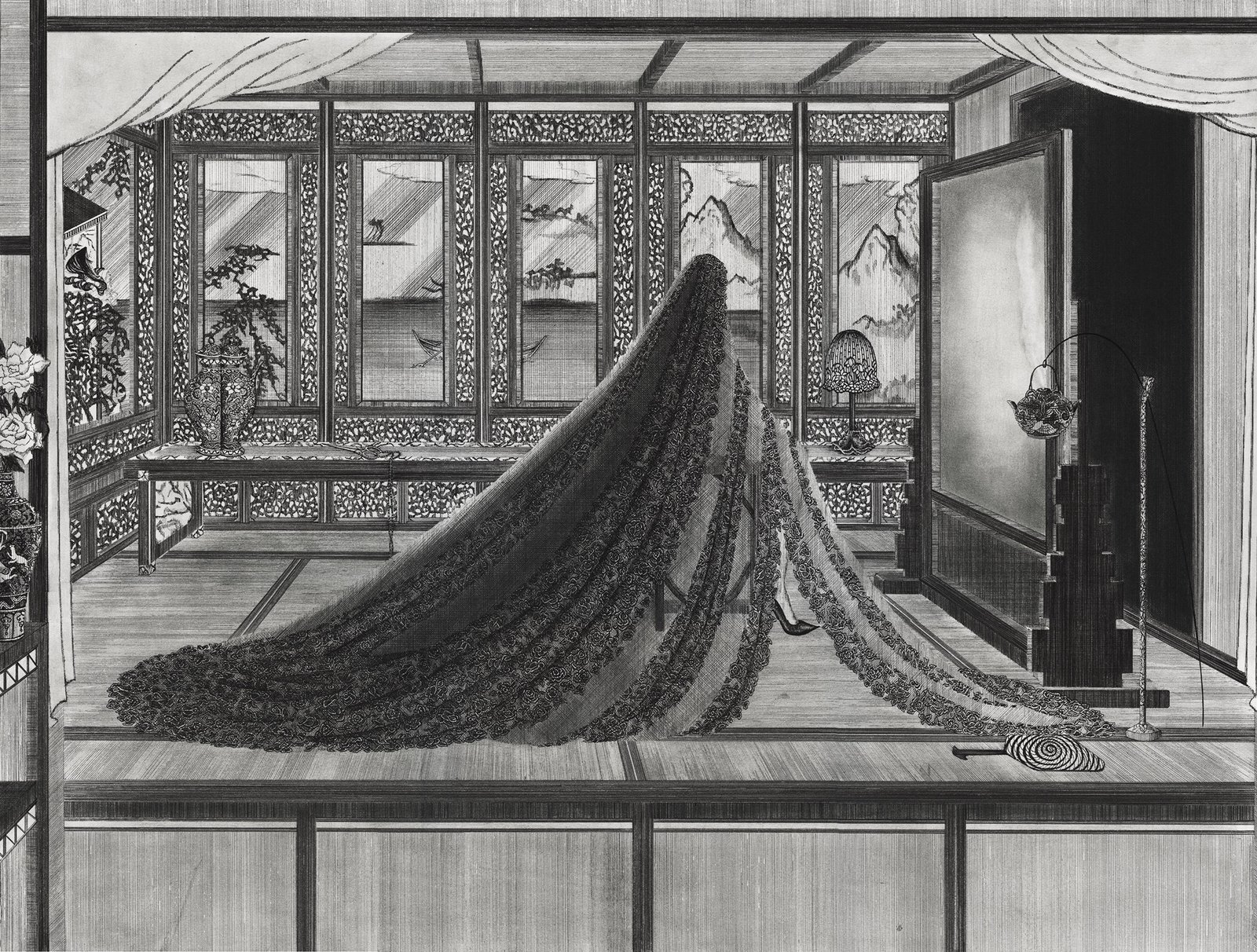

In another Kyung-Me series, titled Half-Mourning, all 2018, each pen on paper drawing comprises a camouflaged widow and a haunting presence. The widows are dressed in Victorian veils and sulk stylishly in jam-packed, Anglo-Japanese rooms. They bide their time until the end of mourning. The rooms contain all kinds of gay things: a fur shawl atop a Byōbu, a Japanese folding screen decorated with a gloomy illustration of a hunter and horse, dreary, ill-defined rugs, more velvet curtains, a few patterned porcelain vases, a single hanging tea kettle, embossed screens decorated with deer, dragons, and phoenixes, a lumpy chaise lounge and wicker wood throne. There’s a lot going on, and it feels like dread, both localized and diffuse.

Like the stuffy halls of Kyung-Me’s cathedrals, okiyas, and waiting rooms, the artist’s figures hide inside the spacious rubric of our imagination. There’s very little flesh or skin in her ultra-ornate drawn figures. In the Half-Mourning series, what is revealed to be the skin of an ankle atop a black stiletto pokes out from a widow’s veil (Half Mourning II); the bare neck and shoulder blades of an unveiled widow wearing a black evening gown (Ghost 2) faces away from us and looks at death: he looks back, his hands perched on her hourglass shape, paused amidst a late night waltz. Sure, it’s dark but just a frame. Soon death will slip on by and disappear into the half-mourning sky.

February 23, 2023