Achraf Touloub: paintings as facts of themselves

Breaking lines and signs, saying the opposite of what it seems: an introduction to the paintings of Achraf Touloub

“You never know where you are with an Achraf Touloub work.” I spent a long time thinking this could be the opening sentence of this article on Touloub’s expansive artistic practice. It seemed like a succinct way to convey the disorientation one feels when engaging with the intricate geographies the artist (b. 1986, Casablanca) creates. You see it, and you quickly take in the work as whole, registering an impression, eventually moving in to seek the details. Upon closer look, his pieces start to mean the opposite of what they meant before, or what they seemed to mean. Proximity implies attention. When one reintegrates the parts with the whole, these works revert to earlier meanings, only slightly changed, not dissimilar to the way this paragraph worked for me in writing it: It started certain, it became something else. This feeling is one Touloub shares in creating his own works. “I try to be a bit lost,” he says, “It’s like the way the light reflects on your coffee, and then there’s a sound in the street, from a zero point, this weird reality and encounter. How can I make it live?” [1] The nature of this “how” question is one that I work to understand whenever I see his paintings.

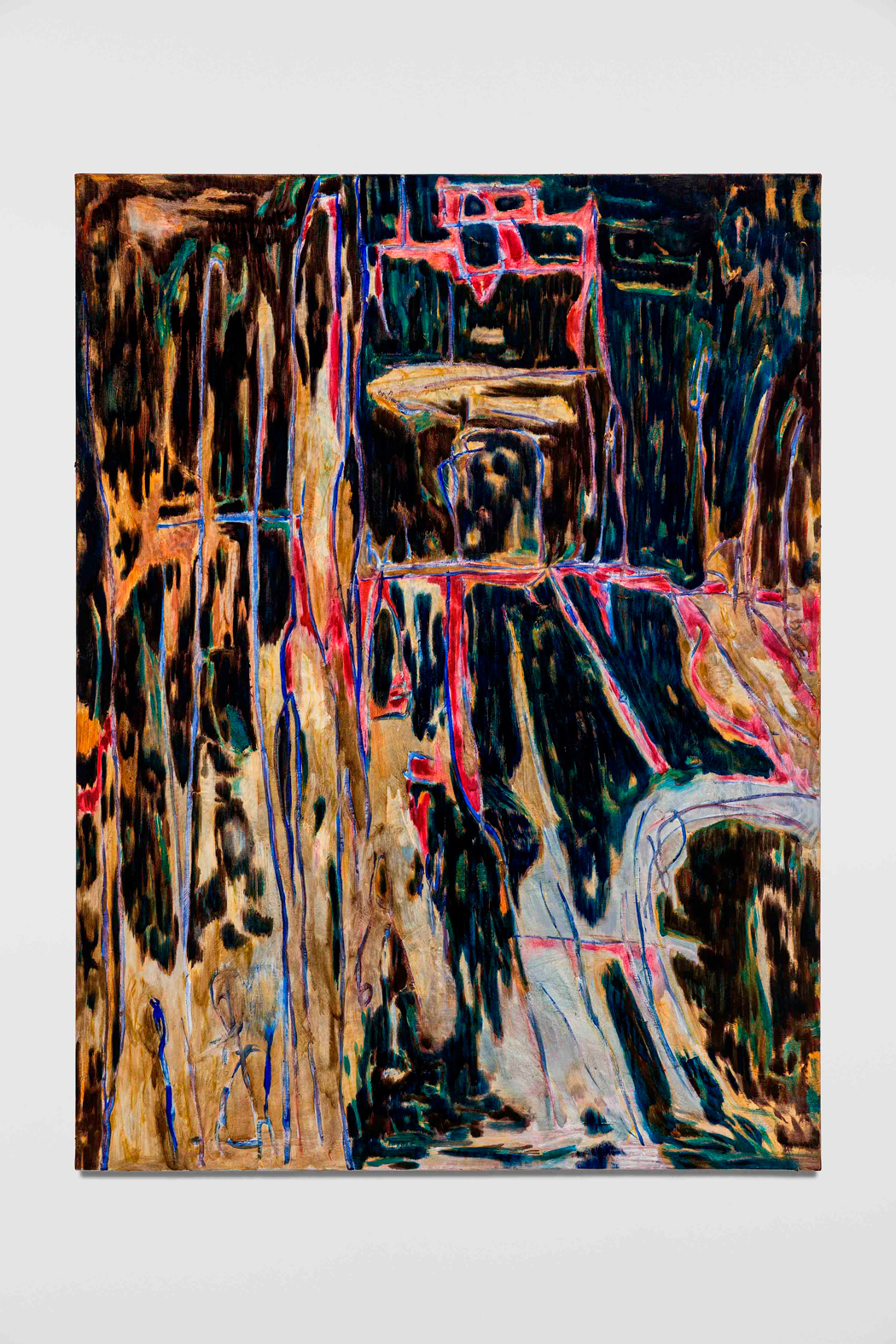

Touloub’s works have a certain concern with presence. It is, however, an unstable concern, less interested in announcing a presence than in probing the idea of what it means to be present, what presence licenses, as well as what it delimits. I first encountered his works as part of an exhibition in Berlin with Harm van den Dorpel at Noah Klink Gallery. The show emphasised the dialogues between van den Dorpel’s digital works and Touloub’s physical ones. While there certainly were ways of seeing that brought the digital vs material discourse to the fore, I found myself becoming more interested in how the artists treated the notions of progress and sequentiality. While time flows forward in van den Dorpel’s iterative works, Touloub’s time is stranger and noisier, recursive still. The “sound” of these works is cacophonous, or perhaps “leaky” is a better term. As soon as one field of colour sets the tonal (in multiple senses of the term) key, the lines within regions begin to contribute their own motifs, sometimes harmonious, sometimes discordant, but distinctive and reactive.

There is a strongly temporal dimension to this aspect of Touloub’s works, which has inspired other writers to suggest he is “drawing time”. I confess to finding this formulation inadequate, or at least inadequate to telling you much beyond the empirical about the works. However, this may not be quite what it seems either, and this is a point Touloub is keen to emphasise: “The quest for antique times is a natural challenge for artists. The new sophistication in art is to be archaic. To be outside of the structures of national states and identities. Delacroix or Matisse felt it when they went to North Africa. Every time you have a revolution in the world, you have to redefine reality. Today, it’s no longer just a European practice; it’s a global one.”

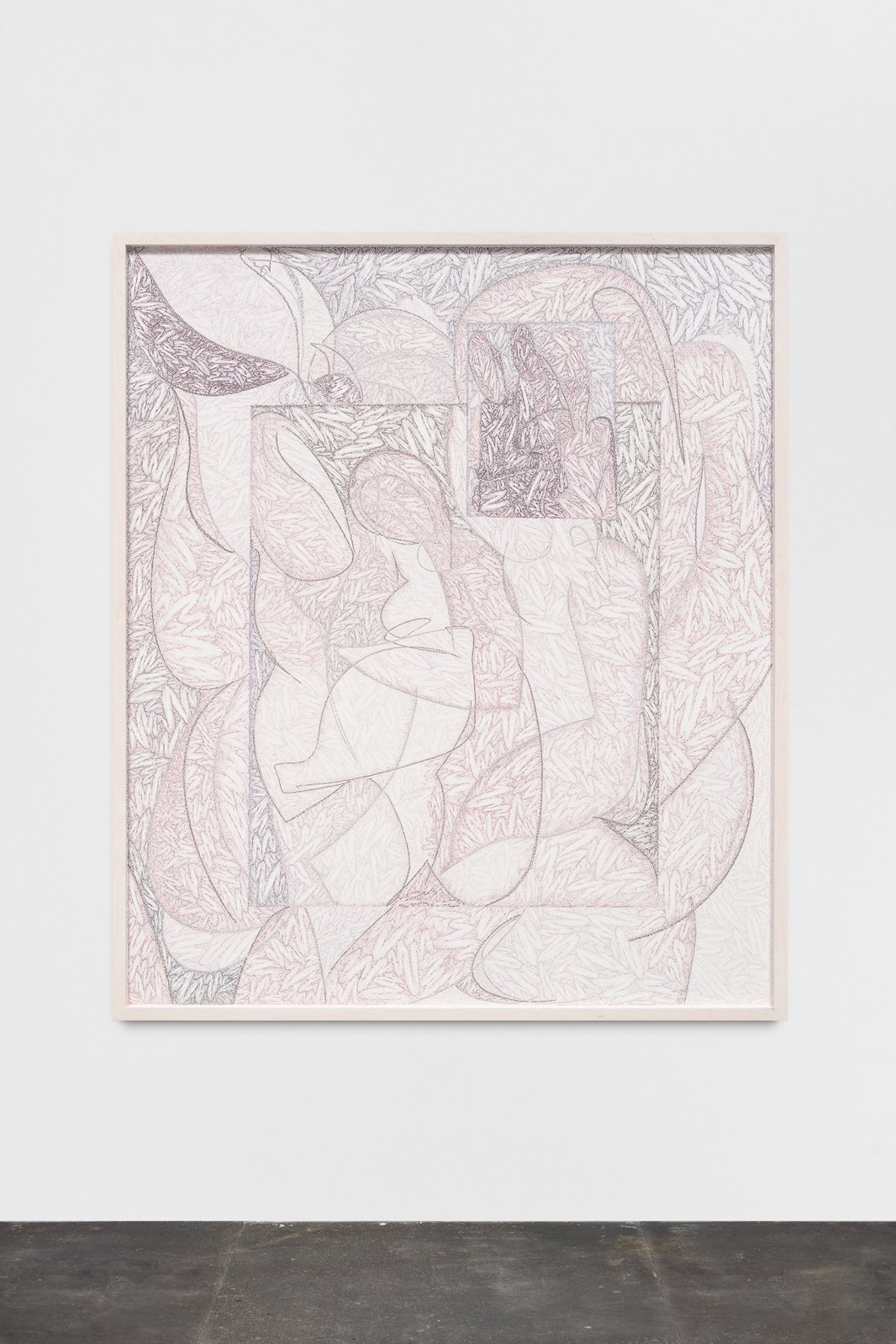

In the global practice Touloub describes, time is far from a monolithic concept. Among the most contentious elements is the question of its linearity: Is time a line or a circle, or a network of concentric circles? Aren’t circles lines too? A physicist would answer that it is just a matter of visual representation, illusion even. In block time – a technical term from physics referring to all time from the beginning to the end of the material universe – time is contained. The notion touches on an aspect of Touloub’s work: the artist denies time’s linearity, ironically through lineation.

Touloub’s lines don’t pretend to be anything else, which can be confusing in itself. What is a line after all? They don’t really exist in nature. All lines are illusions of a kind, an abstraction, but they are also the blunt fact of themselves. Touloub says: “The quality of the line in ancient European art was a discovery for me. Straight beautiful lines in drawings reminded me of the idea of progress itself. Artists from Persia or Japan developed lines differently, as a multiplication of small commas together, giving a weird brevity to them. This was a starting point for me. The line becomes more than just a way to define territories; it becomes a way of thinking, or a scheme.”

[On geometry in North African art, here is an interview with expert art collector Sooud Al Qassemi. Ed.]

A line, even one that pretends to be only a line, is a kind of illusion. The status of the illusion in Touloub’s work is an idea he keeps coming back to in our conversation. Is the illusion to be found only within the framing edge? Or does the illusion really start once you’ve moved outside the frame into what we call the world? I am reminded of a scene in Roberto Bolano’s 2666 in which characters are fascinated by an optical illusion: a picture of a “little drunk” laughing. If one flips the pages, a picture of a jail cell blurs over the image and the drunk appears to be behind bars. The narrator poses the question of whether the viewers are laughing because the drunk doesn’t know he’s in prison. Or is the drunk laughing because the viewers think that he is in a prison?

[Read more on art and optical illusions through the work of Kate Mosher Hall here. Ed.]

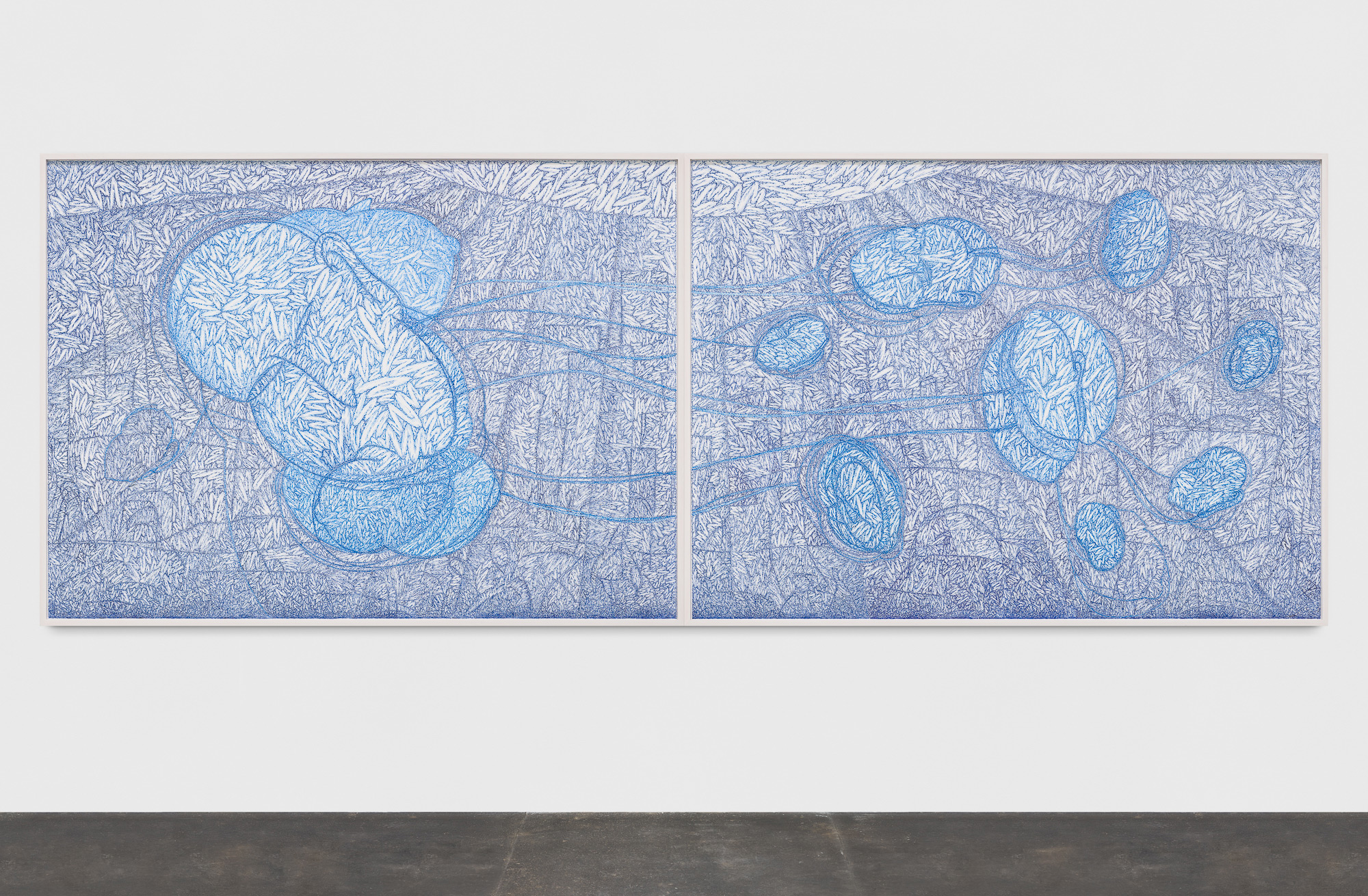

For all this discussion of lines and mark making, Touloub’s work is self-consciously representational; it is not simply a matter of lines and colours. His recent exhibition at Plan B in Berlin is a case in point. In the show’s press release the exhibition posits the notion of “figures as vectors”. Vectors for what, exactly, I wonder. There is a certain literal character to the description, in canvases such as Dei Frari and The Path (both 2022), where lines extend from figurative forms outward into the composition. They are not so much materialisations of specific emotional or psychic states as they are expressions of the permeability of bodies. An internal tension exists in these works between a post-quantum notion of entanglement of entities that are composed of bodies or forces and the theories of Al-Kindi, a crucial figure in the Arabic Enlightenment and author of an early treatise on optics, titled “On Stellar Rays”. Al-Kindi’s arguments for a projective relationship between vision and light come in handy. Projections touch surfaces in Touloub’s work, but they also permeate, thus they extend beyond being vectors to being a kind of connection point. The picture for Touloub is not merely an icon, but a location, a place of dialogue. “A painting is a meeting point,” he tells me, “beyond the brain or the mind, we can meet there.”

September 22, 2023