On artist, psychiatrist, and collector Roman Buxbaum (and Miroslav Tichý)

A portrait of Roman Buxbaum, initiator of the Tichy Ocean Foundation in Zurich and custodian of the Artists for Tichy – Tichy for Artists

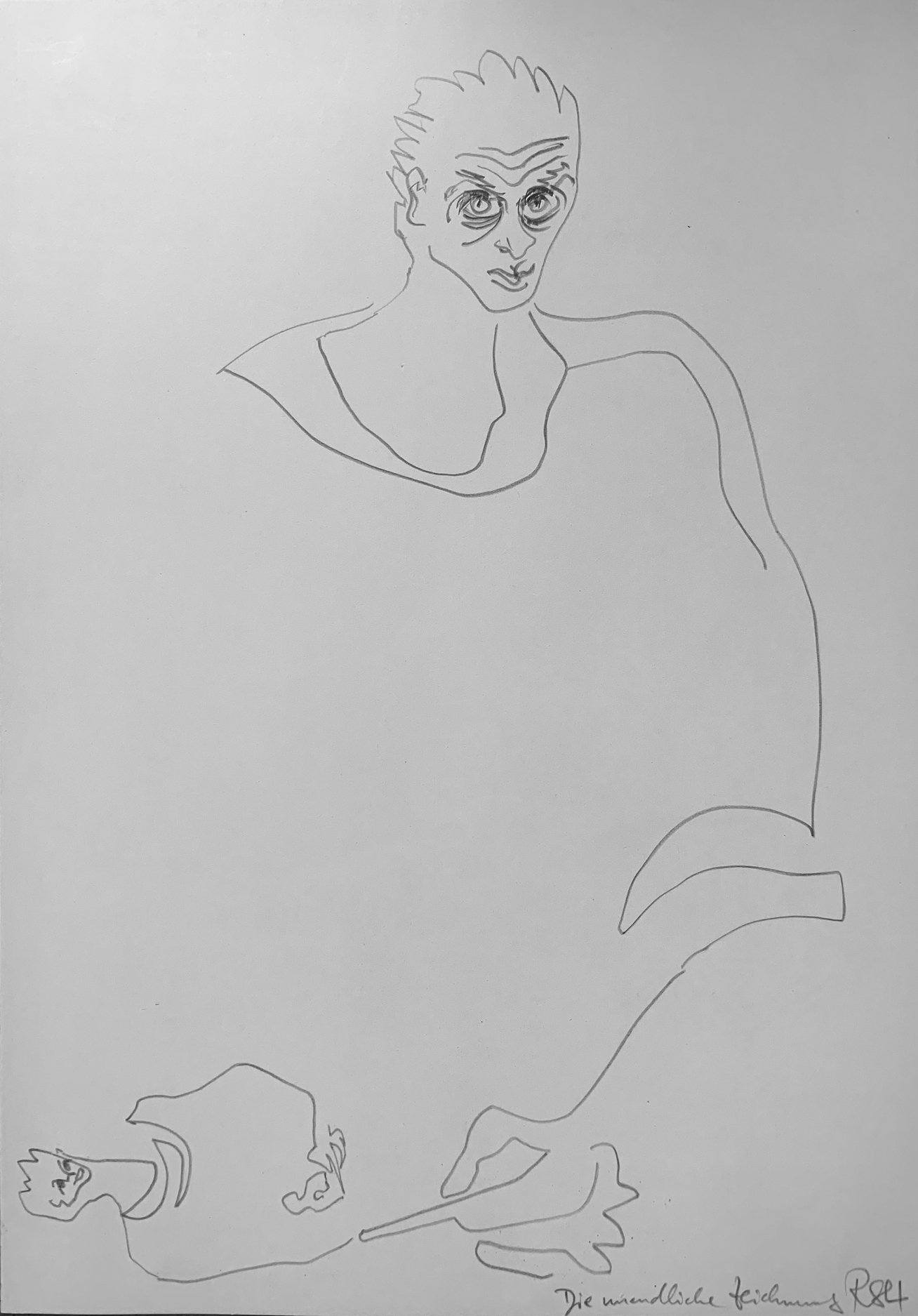

Zurich, Winter 2022. From the little terrace, I look at a red Lawrence Weiner phrase saying “After Any Given Time” on the wall of their house. Up the stairs, in the loft, I am greeted by an older man; I introduce myself. Roman Buxbaum is tall and generous. I ask about the drawing in the living room, a work that caught my attention earlier amidst other artworks in the house. It is a portrait of a character with dark, rimmed eyes–the pencil repeatedly tracing the under-eye bag. On the lower left side of the drawing, a single line develops into a smaller figure, seemingly drawing the main one. “Oh, I drew that”, Buxbaum says. I honestly think: “Bingo”. Our conversation goes into his multifacetedness; running the art space downstairs, being a collector, a psychiatrist, and an artist. He smilingly says he might invite me for a studio visit, something he hasn’t done in over a decade. I email him the next day.

Three weeks later I sit across him and his wife in that same living room, drinking Prosecco. We’re atop the Psychcentral, the clinic they run, employing some 35 psychiatrists specializing in various fields. I wonder what we are going to talk about over dinner, until he later starts telling the story of how, years ago, he decided to let a benign tumor on his shoulder grow. The eventual surgery to remove it was intended as a theatrical performance, taking place at the Rudolfinum art gallery in Prague. He points at a pedestal behind me, on which a subtle, beautiful bronze undulation is a cast of this very tumor. “Lipomas are easily removed: the skin is cut open in the direction of the crevices and the lump lets itself be peeled with a finger, like an orange,” he specifies. A simple and satisfactory medical procedure, in comparison with his slow work as a psychiatrist.

Everything was ready for it: printed invitations, stage, video screens, script, lights out, and applause. Unfortunately two days before the surgery/performance the Medical Chamber of the Czech Republic deemed it unethical and stopped it. “When the surgeon was not allowed to come to the theater, the theater went to the surgeon,” Buxmaum says. In a small private event, Dr. Christian Roy removed the lipoma with a Japanese samurai sword from Buxbaum’s shoulder. A camera crew captured everything. Impatiently I tell them about one of my performances, titled Pharmakon, with my duo CMMC, in which we received a massage for 6 hours a day, 4 days in a row. The evening continues with stories merging mental, physical, and artistic health.

That night, Buxmaum even offers me a job: I should write on his 20 year-old career as an artist for an archival website. Given the drawing and the lipoma performance, I express interest. He also has another job for me: I should somehow turn into an art project, him and his wife making a child with an egg donor.

The Collection

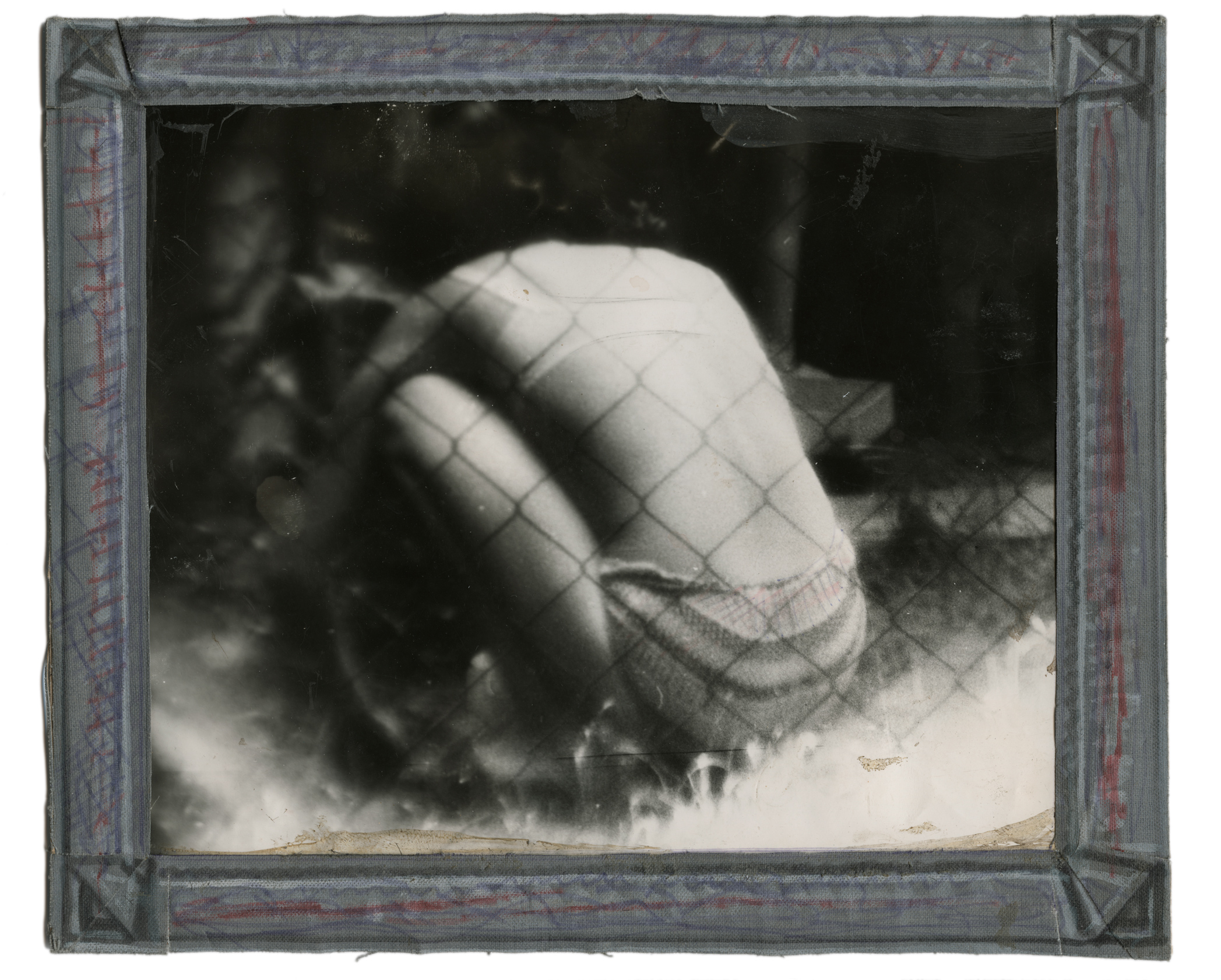

The life of Roman Buxmaum as a collector starts with Miroslav Tichý (1926–2011), a person who is both world-famous and nobody around me has ever heard of. A painter and photographer, he was born in Kyjov, Czech Republic, where he spent most of his life. Despite his art education, he was considered an outsider because of an eccentric approach to his medium. He often used self-made cameras to shoot one hundred images a day on average. The main subject of his study were women unaware of his gaze. The work celebrates the charming mistakes that border black and white image-making and mysticism. Over time I learn that Tichý was a friend of the family where Buxmaum grew up. In 2005, the latter established the Tichy Ocean Foundation in order to collect, preserve, and exhibit the works of Tichý. Photographs, drawings, paintings, prints, and his self-made cameras make up the Miroslav Tichý Collection, which has been exhibited in over a dozen international shows organized by Buxbaum in venues such as Kunsthaus Zürich, Centre Pompidou Paris, and ICP New York to name a few.

When Arnulf Rainer visited Tichý in Kyjov, the latter refused to sell any of his works to the latter, yet didn’t mind trading. The project that followed, called Artists for Tichy – Tichy for Artists, flourished in 1992: it consists of exchanges between Tichý’s photographic prints with works by artists who admire him. Many of Tichý’s pieces now reside in the homes and studios of these artists. He passed the project to Buxbaum, who has been running it since, under the umbrella of Tichy Ocean Foundation. The catalog counts over 300 artist trades.

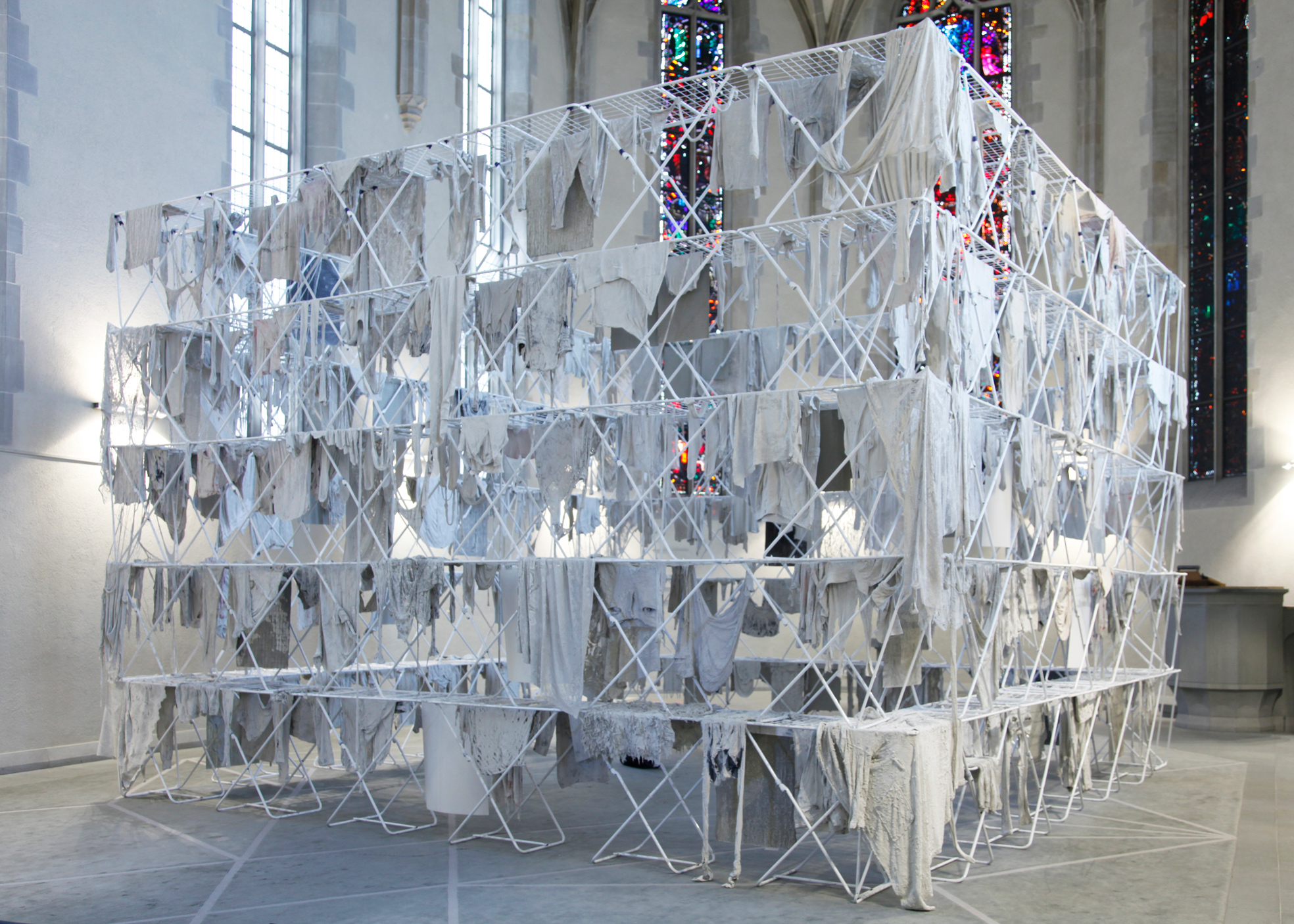

Apart from the oeuvre of Miroslav Tichý, Buxbaum now owns the continuation of his exchange project, including pieces as large as a magnificent cage piece by Eva Koťátková. The collection seems to make so little compromise. Since the premise of the project is based purely on exchange, little to no money comes into the picture. (Buxbaum still buys more affordable pieces on occasion, like an edition by Richard Prince.) The “Artists for Tichy – Tichy for Artists” pieces cannot be sold afterwards, and are contracted as such. Quite a stance.

Buxbaum tells me about visiting Weiner right before he passed, finding his studio empty aside from two prints by Tichý by the sink. He’s also friends with Nick Cave, from whom he has signed t-shirts for his daughter hanging in the library, which is separated from the living room by a large Gunter Förg painting. The collection built on Tichý’s exchange project is extensive, forming the largest Czech contemporary art collection to this day. Going back to his roots, Buxbaum is hoping to found a museum for the collection in the Czech Republic one day.

The Space

Under the name of Tichy Ocean Foundation – Salon Lessing, the headquarters of Roman Buxbaum host contemporary art exhibitions on the ground floor, as well as parties and talks, binding international artists, Miroslav Tichý and thoughts on the health of the human psyche. Exhibitions, which are managed by Buxbaum and Angelo Romano (former curator of Counter Space), rotate quarterly, featuring artists such as Valentin Carron & Jacques Chessex, Alfredo Jaar, Stefan Vogel, Paul McCarthy, Damien Hirst, Christian Jankowski, Jürgen Klauke, Jiří Kovanda, Urs Lüthi, Jonathan Meese, Peter Weibel and David Weiss among others. Prof. Wolfram Kawohl gave a lecture, and Prof. Dr. med. Erich Seifritz discussed ‘Psychedelika in der antidepressiven Therapie’. Sometimes Buxbaum opens the rest of the factory building as a private museum, in which the first floor showcases artworks by patients of Psychcentral, the second floor holds temporary exhibitions with pieces from the art brut collection, and the top floor, Roman Buxbaum’s loft, houses works from the Artists for Tichy – Tichy for Artists project.

Currently, for Zurich Art Weekend, Malaysian artist Mandy El Sayegh shows large-scale paintings, sculpture and a multi-media installation between Salon Lessing and the Wasserkirche. The website reads: “There are clear references to historical violence in the material, but also a focus on painterly techniques, which combine to express the artist’s long-running interest in how artistic processes, specifically the use of layering and transparency, can be used to subtly question inherited power structures.” It’s fascinating how the occupations and artistic, curatorial and professional choices of Buxbaum keep overlapping while spanning over quite a vast network.

The Artist

The work of Roman Buxbaum as an artist looks into the human psyche as a thin fragile foil. Through the media of performance, sculpture, drawing, theatre and painting, he seeks transparency and time. One of his earlier projects used an outdated psychological test that made use of facial features to identify personality traits. The posters that came out of it were pasted all over a Czech city overnight. He says the local population was still unfamiliar with posters as a post-communism format, and the images remained in the streets for years after.

His background as a psychiatrist heavily informs Buxbaum’s artistic practice; from the poster work to his elegant but complex early days’ self-portraits, to examining the connection between twins. Medicinal tools like X-rays and psychological tests serve him almost to look through a person, and even surgical elements find their way into his art. In a sliding-scale-type-of-relation with past and future, the practice of Buxbaum thinks through the bonds of family and the material that makes up a life. His mother, grandmother and daughter all appear in his still or moving images. He seems to capture the anticipated loss of a “now”, and in that sense maybe the practice of Tichý is never too far off; images fading in full sight, intimate yet distant observations.

Buxbaum shows me an earlier work in which he took all things from his grandmother’s attic to build a house, including half a dozen chairs and a life-like set up in it, waiting to host. The sculptural installation was presented at Kunstraum Aarau and Kunsthaus Biel – Centre Pasquart in 1992; it reminds me of a Béla Tarr scene, the atmospheric setting that can host innumerable situations, yet always coated in suspenseful gloom. After the exhibition he cut all the furniture in slices, stacked the wood, and put it back in the attic.

Buxbaum turns around to reach for a book behind him and without looking at me he says: “all the work is quite melancholic.” We speak of time passing, absorbing; he mentions images dying. In recent years he has been wondering about exactly that: whether images come to die. As he describes it, he uses his art to desensitize from what causes him fear, leaving the viewer with solid feelings of evaporation of the self, body, time and space. He is an artist, collector and psychiatrist whose carcinophobia inspires art as a form of self-therapy, as he likes to put it.

In his interactive theatre performances in the late 90s, performed at Wiener Festwochen, Theaterhaus Gessneralle and Theaterspektakel Zürich between 1997 and 1999, Buxbaum put on stage his own granduncle, a Holocaust survivor. Throughout the performance, he appeared to not be narrating a fictional script like an actor, but rather his own life story. In a variety of ways, he seems to make rearrangements, pulling things from one register into another, never shying away from an uneasy tension.

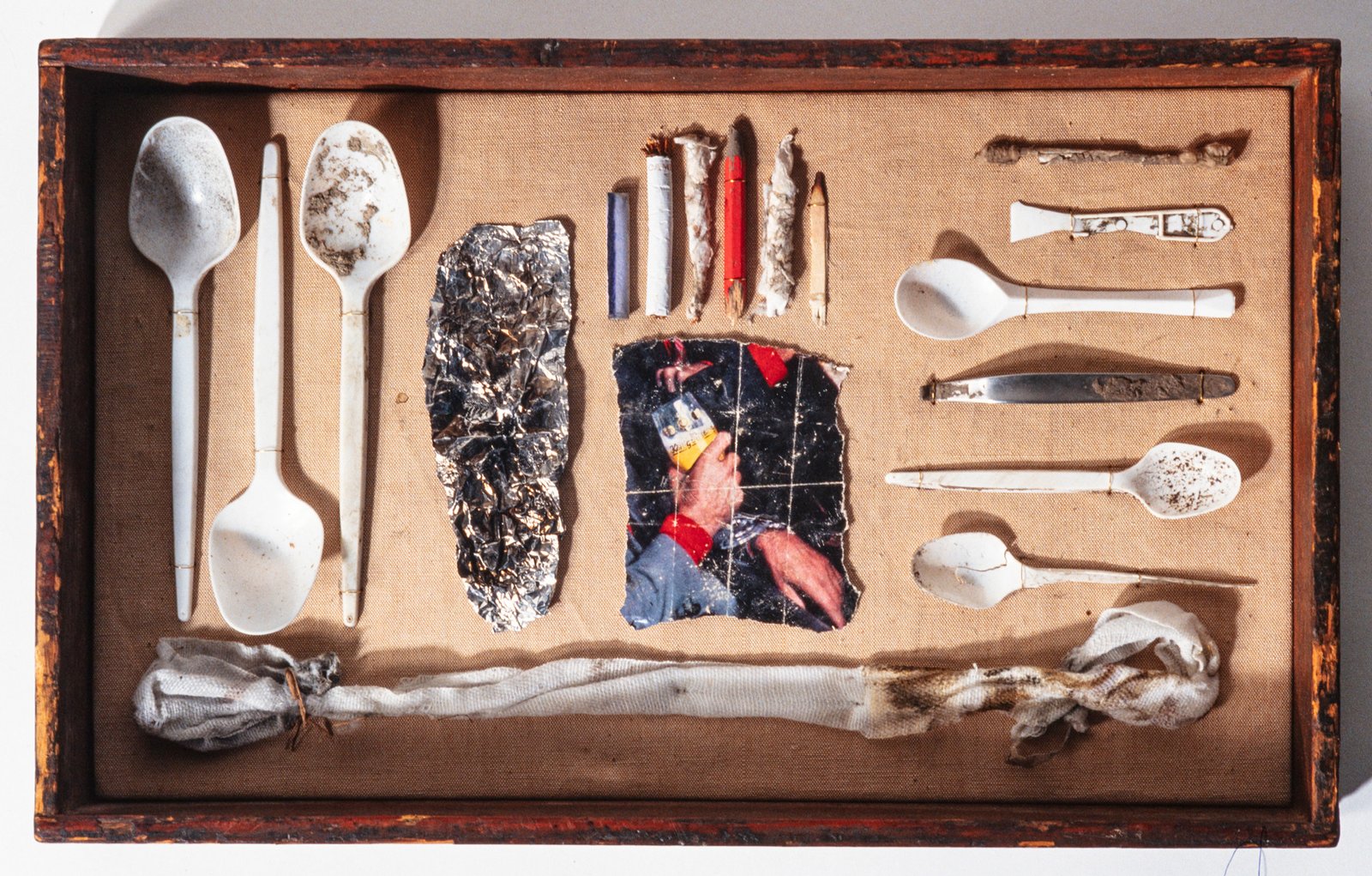

During a heroin crisis in Zurich, the city’s authorities asked Buxbaum for his professional advice as a psychiatrist; he eventually instructed them to provide clean syringes and everything else they needed to use the drug safely. (For a while, each exhibition venue in which Buxbaum showed was equipped with a candle, a strap, syringes and thinning fluid.) In that period he collected used syringes and bloody cotton gauze for his own artwork. He also photographed the hands of drug users, hammering these small pictures to the trees when the most popular needle park was closed. The thing he says about the piece – to work with what he fears most – marks it especially well.

The End

Both looking at me and not, with a moment of hesitation, Roman Buxbaum says what he finds hard to say: “Elena and I would like you to consider giving us your eggs.” I try to keep my face neutral; I have already been thinking about the request since our dinner, obviously, and tell him so. I need more time to think this through. Hours later, Hours later, I wonder who would be having a child, through, and with whom? He would have a child with me through Elena, but the child would mostly be Elena’s. Is it calculated in the equation that Buxbaum will not live forever? Would they be having a child through me, or would I have a glimpse of a kind of parenthood through them? Or is this story a multiple and far-driven psychological exercise? A few weeks later, tests done in preparation for the possible egg harvest show I have a large benign lump that needs to be removed–images die and growths continue.

May 23, 2023