Hanne Lippard: “The mouth is always my favourite medium”

A portrait of Hanne Lippard, an artist whose text- and performance-based work reveals the emotional and political values of semantics

Let’s start with the mouth. A picture of a woman’s tongue reaching out to press heavily on a typewriter key. The photograph by Brazilian artist Lenora de Barros from the work Poem, 1979, which I wanted to share with Hanne Lippard at the time of writing this article about her art, [1] appears on the cover of the book “Women in Concrete Poetry 1959-1979”. [2] This anthology of concrete poetry by female artists pays tribute to the first historical exhibition dedicated to women at the 38th Venice Biennale, “Materializzazione del linguaggio” (Materialization of Language), conceived in 1978 by the Italian poet and artist Mirella Bentivoglio in reaction to the invisibilization and silencing of women. The exhibition brought together the works of 90 international women artists and poets, delving into the relationships between the female body, language, and its bodily materialisation through images, text, and performance. (A naked Tomaso Binga drawing letters of the alphabet is but one example.)

In the 1960s and 1970s, audiovisual and typing technology became more accessible, offering artists independence and immediacy. The portable machine became the tool for a new, self-determined production: think of Carla Lonzi’s tape recorder, without which she would not have been able to conceive her experimental book Autoritratto (Self-portrait) [3] on Italian art of the 1960s, based on recorded interviews and recomposed in an original textual montage; or the Sony Portapak camera, which was greatly used by the feminist collective Les Insoumuses [4] (“Disobedient Muses”), founded by Delphine Seyrig, Carole Roussopoulos and Ioana Wieder, and paving the way to a new subversive video documentary approach.

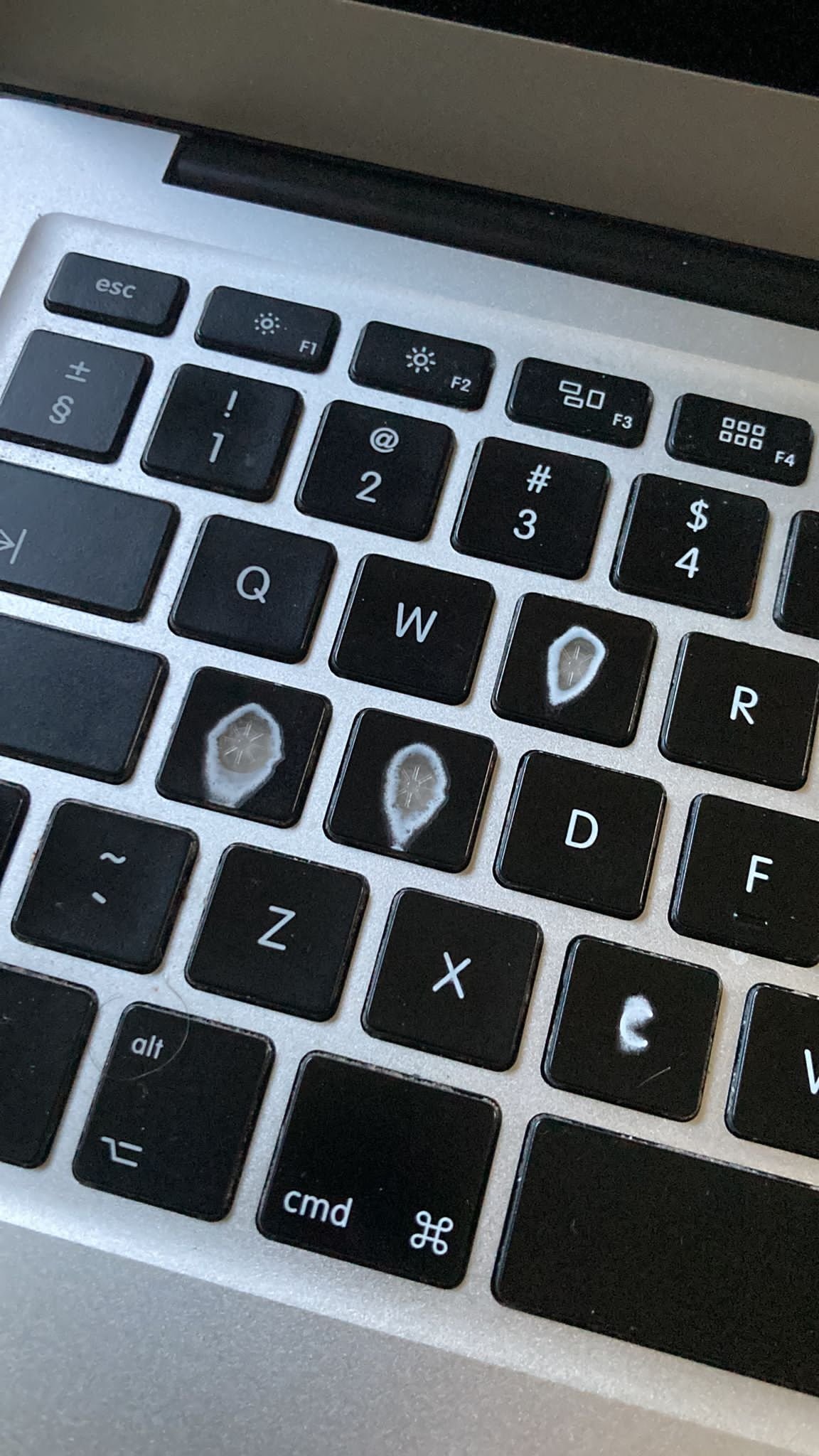

Let’s go back to the initial photograph by de Barros, the weight of a tongue on a letter of a typewriter keyboard; by coincidence the letter is “H”, the first in the artist’s name: Hanne. This is an image of flesh and blood technology, helpful to approach the pregnancy of language in Lippard’s work and in today’s technological world with its promises for a full digitization of life. The same weight of language has been erasing three letters in Hanne Lippard’s computer keyboard, the letters S, E, and A revealing its concrete relation to text and poetry: “What does it say? You see; I never miss the sea until I see it again in front of me and I say it out loud; I miss the sea.” [5]

The body’s relation to language and its vocalisation through performativity of words has been intimately evolving in history with the need to subvert the authority of the art object. Hanne’s surname, Lippard, beautifully and coincidentally spells like that of the curator and feminist activist Lucy R. Lippard, to whom we owe the famous chronological volume on the phenomenon of dematerialization of art: “Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972”. [6] (Hanne would not ignore the coincidence and form a Berlin-based band called Luci Lippard, together with the artist Lucinda Dayhew.)

From the mouth to the tongue, Lippard’s measured voice, at times turning hypnotic, repetitive, sensual, phlegmatic, or robotic, is her favourite medium. Recorded on a digital tape recorder, read or performed in the presence of an audience, the voice varies in tone and rhythm, playing with the spectator’s attention through a game of associations, onomatopoeias, homonyms, and syllables, while modulating the space it finds itself in.

Lippard trained as a graphic designer at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam but soon became interested in the phonological subtleties of language. Born in Milton Keynes in England, she grew up in Norway and learned Swedish, German, Dutch, continuing to nurture an insatiable desire for languages even later in her life. Her piece Ownwords, 2021, demonstrates this interest by declining a series of words in different languages, revisiting a conceptual work by Portuguese artist Ernesto de Sousa titled Palavras Proprias e Improprias (Proper and Improper Words) from 1978. In Ownwords, Lippard consumes language as a substance, kneading it as acoustic material in space. Through sound, text-based installations, and performance, the artist explores the emotionally charged systems of intimate and public language, exploiting combinations and permutations of words and sentences, drawing inspiration from the algorithms that rule our daily internet.

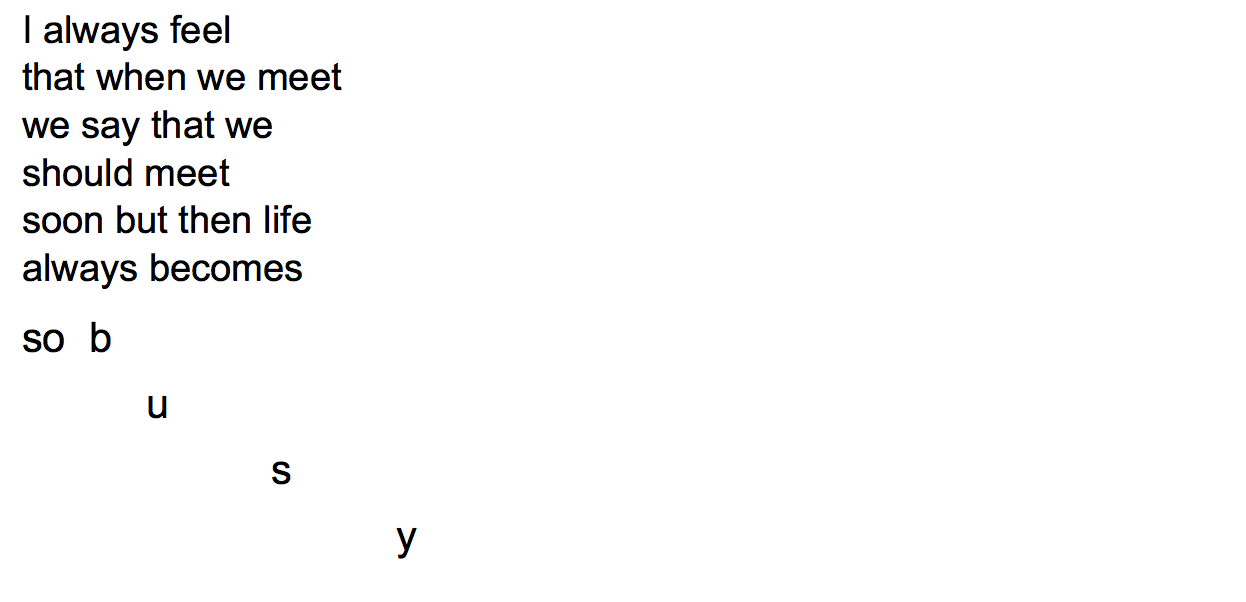

She collects words and fragments of sentences gleaned from everyday life (advertising texts, slogans, news, etc.) or from literature, creating textual and sound collages in an associative way. In the piece 101 Misspelling of Cappuccino, 2016, one can read or hear passages such as: “Ciaoppuccino”, “chap pachino”, “crappuccino”, “stress presso”, “ness-presso”, “de presso”. In the series of poems Contactless, 2020, she reveals the melancholic emptiness and the paradoxes of our languages emerging at the frantic pace of a hyperconnected work environment:

Lippard’s texts probe the depth of language, its evanescence, and depersonalization through collective simplification: The emoticons she frequently incorporates into her pieces speak of this quest. In line with concrete poetry, the text, the sign, and the empty spaces reveal themselves and reinforce their meaning in a new visual form of embodied existence.

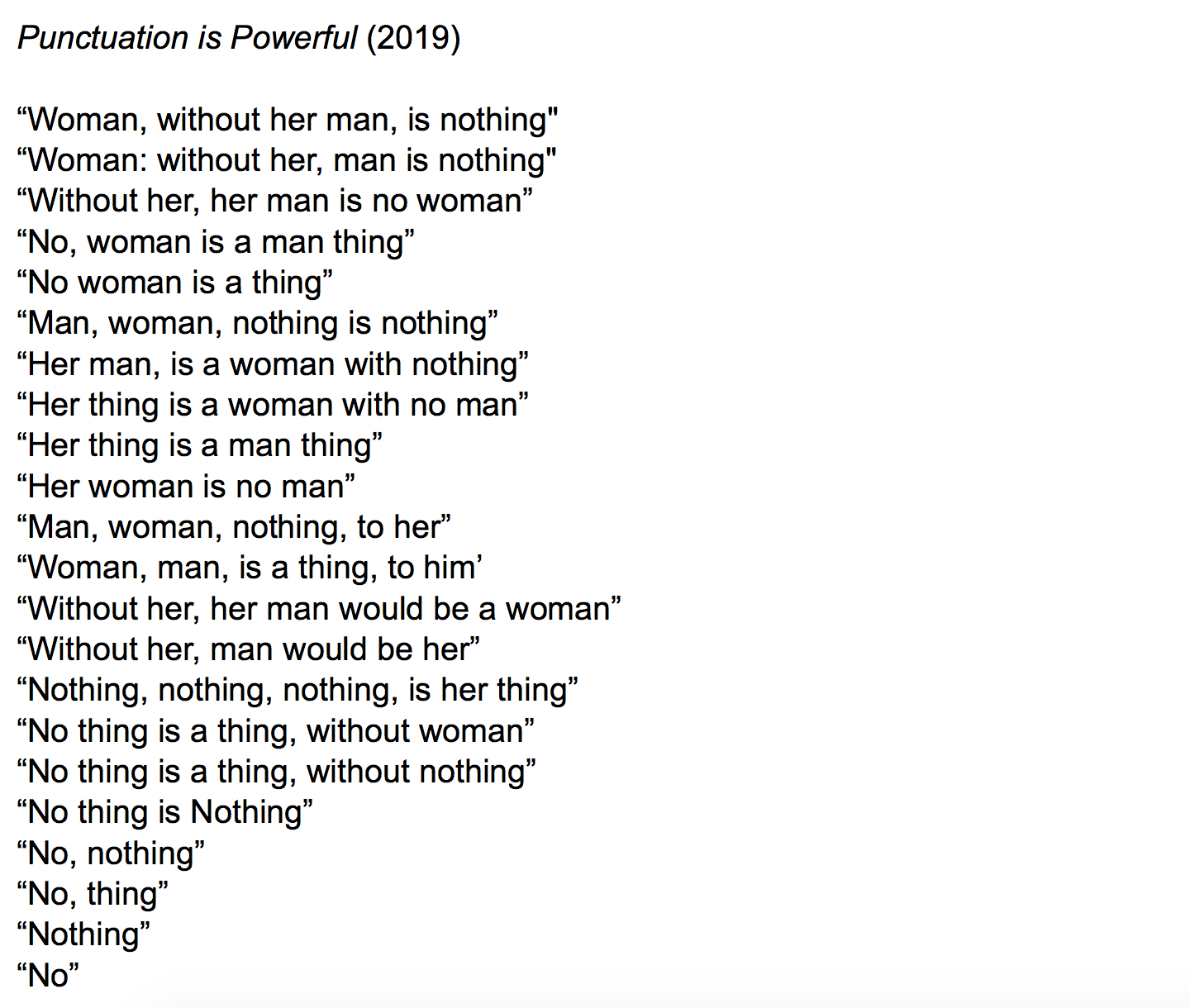

With different ways of dissecting language, Lippard analyses grammar, punctuation, and syntax to reveal the emotional and political values of semantics. In the tradition of pronominal battles inherited from feminist literature such as that of Monique Wittig, each pronoun, comma, exclamation mark, space, syllable, and grammatical rule plays a role in the body of the text.

The onomatopoeia in the word “flesh” led Lippard to choose it as the title for one of her first institutional exhibitions, at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art Berlin in 2017. The installation featured a beige spiral staircase leading up to a cramped space under the roof, which was carpeted in carnal pink. Due to its low ceiling, most visitors could not properly stand up; they were instead forced into a soft choreography of rest – sitting or lying down – to better capture the orchestration of the voice passing from one speaker to the other on either side of the empty space.

“The mouth is always my favourite medium, this hole of expression and consumption all at once,” Lippard said in an interview. [7] The “space of the tongue”, [8] the palate, a cavity with moist walls, both closed and ajar similar to a cave, is the primordial space where language exults in its embryonic form–-from the cry of the child at birth, tensing its rib cage, to the early stage of language. Many fabulous stories were born in the darkness of that enclosed space, like the one of the Pythias of the oracles of Delphi, hidden from ordinary mortals to better transmit their visions and messages of the gods (under the influence of hallucinogenic substances). Connected by an invisible cable to Olympus and installed on a tripod stool, the Pythia embodied a performative voice guided by external inputs, an image that evokes Lippard’s loudspeakers (the “big talker”) in her installations. In her solo exhibition at the FRAC Champagne Ardenne, titled after Roland Barthes “Le Langage est une peau”, 2021, Lippard proposed the viewer a sort of passive and active contemplation on what language tells about itself. In Passif·ve/Actif·ve, 2021, the speaker, whose verticality recalls the posture of a human body, seems to self-reflect on the different meanings of its own name. In English the word “speaker” is both a subject (the speaker who speaks) and an object (the loudspeaker that diffuses sound). Similarly, the word “enceinte” in French corresponds to the object (a loudspeaker), to a protective space (in architecture), but also to a pregnant woman. In these installations, Lippard’s loudspeaker addresses the public behind a veil on a circular structure. The recurring circle in her work defies a clear interpretation but potentially becomes a symbol of the female figure, like the letter “o” of the word “body” in Ilse Garnier’s concrete poem Blason du corps féminin (Blazon of the female body): “body-sun”, body-moon”, “body-orbit”, “body-statement”. [9] Both the poet and the artist evoke the liberation of the female body, traversed by a variety and complexity of languages, able to reinvent its own definition, its own blazon.

Fascinated by polysemy and homophony, Lippard ultimately reveals the poetic, political and symbolic elements of signs and words. Wasn’t the feminine and instrumentalized body of the Pythia of Delphi precisely the vessel of a manipulated oral language, and a “planned obsolescence”?: [10]

“Whether or not she spoke through the force of her own voice or acted as a vessel for the voice of the divine is disputed, as nobody was there to record her performances. The only recorded remnants derive from scripted interpretations of her speeches, noted down and transformed into a logic by a predominantly male audience”. [11]

[1] Our exchange had been put on hold since an email, whose subject mentioned “Mamma” in Italian, overwhelmingly announcing that the artist’s mother had passed away.

[2] Women in Concrete Poetry 1959-1979, edited by Alex Balgiu and Mónica de la Torre, Paperback, 2020.

[3] Autoritratto (Self-portrait), by Carla Lonzi, published in 1969, is the author’s last work of art criticism before she devoted herself entirely to the feminist collective Rivolta Femminile, which she co-founded.

[4] Examples of their work with a portable camera include the videos Maso et Miso vont en bateau (1975), Sois belle et tais-toi ! (1977). The documentary “Delphine and Carole, insoumuses” from 2019, directed by the granddaughter of Carole Roussopoulos, Callisto Mc Nulty, tells the story of the collective.

[5] Hanne Lippard, Mothern technology, ongoing piece.

[6] Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (New York: Praeger), 1973.

[7] Fiac Portrait | Hanne Lippard, April 28, 2021.

[8] I borrowed this expression from the artist Ambra Pittoni, which she shared with me during our last conversation about the “space of language” related to one of her recent project.

[9] For more on this subject see the spatialist poetry by Ilse Garnier, Blason du corps féminin, Editions André Silvaire, Paris, 1979. This is a feminist counter-reading of the classic Renaissance poems “Anatomical Blazon of the Female Body”.

[10] Expression from the booklet of Hanne Lippard’s exhibition “Le Langage est une peau”, FRAC Champagne Ardenne, 2021.

[11] Hanne Lippard, “Tripod”, Look, La Loge, Bruxelles, 2018.

September 4, 2023