Painting genealogy with Gritli Faulhaber

In an attempt to resist the coercion of style, Gritli Faulhaber discusses painting through painting to rethink the medium’s history

Paintings by Gritli Faulhaber are often made up of many smaller paintings that just happen to share a canvas and stretcher bar. A vivid compendium of collected images is arranged breezily, but not randomly, across a large plane – often making up works of three to four metres long – or like in her most recent show at Theta, New York, across multiple smaller works. In an impressive parade of technique and style, Faulhaber’s assemblages negotiate the parameters of painting as a medium and her own tender but ambivalent relationship to it.

Montage: Chronic State of Becoming*

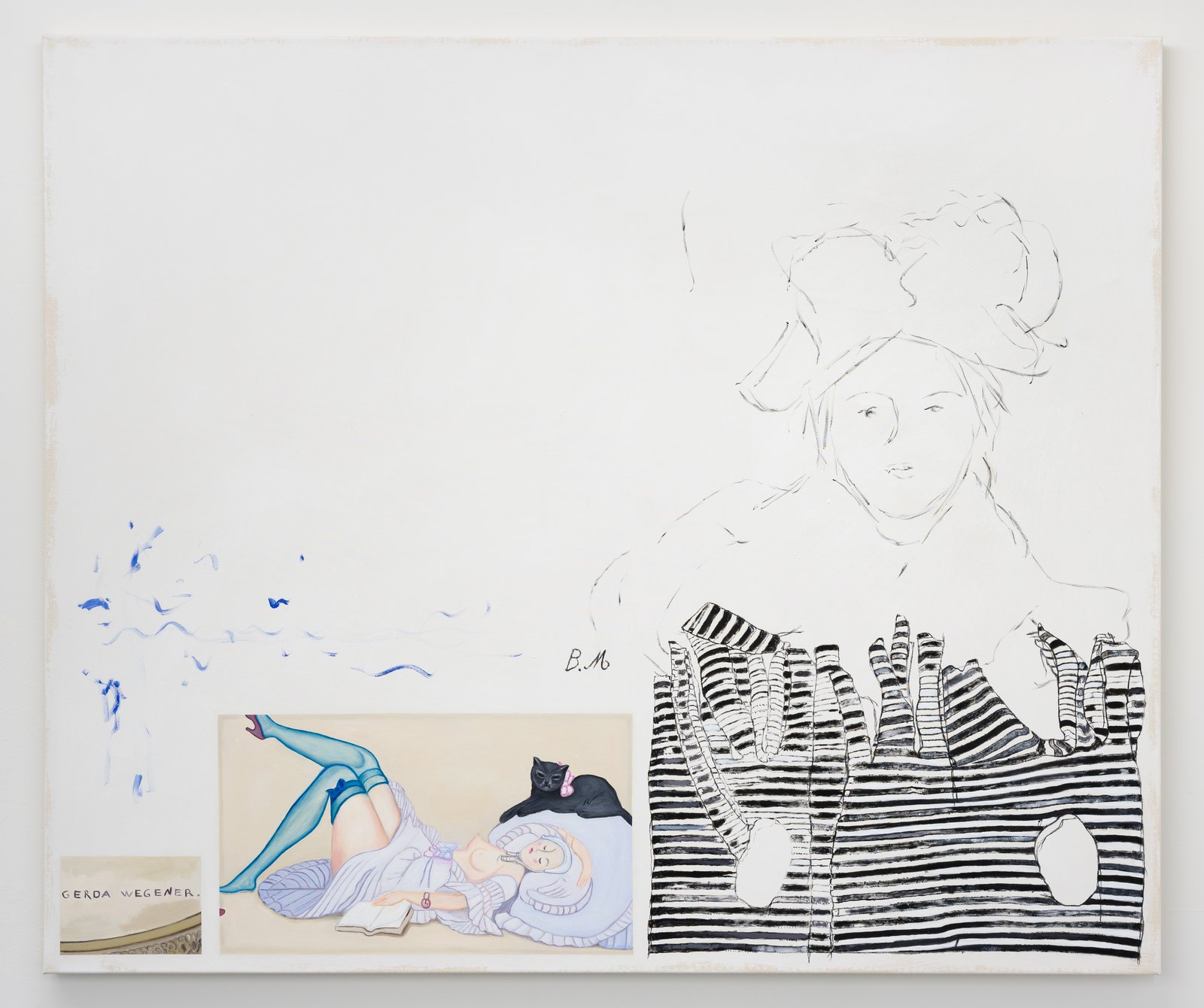

Many of the images Gritli Faulhaber uses are part of her personal archive of A3 printed sheets, an inheritance from the days of free printing at art school, which over the years took on a weighty, physical presence. Throughout the vast range of material, certain themes recur. Classicism, historical works by female painters, snapshots taken on a phone, screenshots, book covers, the odd garment of clothing, and other footage from her daily life. In 2023 Faulhaber presented a series of these large-scale panels in a duo show with Costanza Candeloro at Instituto Svizzero, Milan, designating them all Ohne Titel. In Ohne Titel (2), three oval medallions by Danish erotic illustrator Gerda Wegener are placed next to a quote by contemporary painter Maximiliane Baumgartner, a sketch of Cardi B and a portrait of a mother and baby. Despite the rich imagery, much of the plane is left blank, or even jokingly painted “blank”, in a trompe l’oeil whitewash mimicking a void. A tiny snail, perhaps but not necessarily a nod to Krebber, sits comfortably in the centre. Faulhaber manages to weave these vignettes harmoniously, following a “choreography of emotions”, each composition flowing in its distinct tempo while remaining playful and light-hearted.

So how does a painting of a Billabong shirt hold up next to a portrait by impressionist painter Berthe Morisot? What happens to each image when viewed in proximity to another, vastly different? For Gritli Faulhaber, all her images are of equal significance, regardless of age or context. In 2019, Jack Self coined the term Big Flat Now to describe the de-hierarchisation of all media in the age of immediate communication. In a post-information age, where everything is accessible at all times, the contemporary emerges as a category of the coevality of juxtaposed references. If montage, as a term that entered cultural vocabulary through left-wing cinema at the beginning of the 20th century and used to describe the jarring effect created by juxtaposing seemingly unrelated content, could once have been pitted as the opposite of curation, a mean of pointing out analogy, I wonder if this distinction holds up in a flattened cultural plane, where creation and consumption merge into a fluid continuum.

What in a previous generation of artists could have been taken as a daunting existential proposition; that there is nothing that has been done before, and therefore no such thing as authenticity, is in Gritli Faulhaber’s work embraced in buyout optimism. If nothing has been done before, everything is possible. It is in the act of montage, or curation, that the new emerges in the endless possible connections made between that which already exists. For a generation raised on social media, to “construct oneself with pictures” has become the modus operandi of cultural consumption. Faulhaber’s panels, too, could be read as a kind of self-portrait, revealing a glimpse of her habits, thoughts, and context of painting.

Style: The feeling of historical Unease, mainstream Criticism, Loops of inequality, Endless references, loss of sincerity, Abuse of Power or Just a Green painting

But Gritli Faulhaber’s aim seems a lot less solipsistic than mere self-actualisation. At the end of the day, her paintings always loop back to painting itself. She once described herself as “less of a painter, and more of an artist whose research matter is paining”, explaining how her own relationship to the tradition-heavy medium is always at stake. It is through this gaze from the outside that the eclecticism of not only her subject matter but also technique is driven.

In The Living at Theta, Gritli Faulhaber’s brushwork switches from delicate, impressionist oil to heavy impasto, sometimes using gluey, textured primers and sometimes none at all. When asked about her work, one of the first things Faulhaber talks about is the looming pressure of a tightly-coded German painting tradition to cultivate a signature style, which even led Faulhaber to quit painting altogether for some years. But by the time she had left art school she was back to painting, this time allowing her conflicted feelings towards the medium she nevertheless felt so drawn towards steal the limelight.

Less interested in signature, and more in the multifaceted possibilities of the medium, Gritli Faulhaber will use a range of techniques to tell different stories, compassionately attuned to how a certain subject matter flows across a canvas. An image of an infant playing on its mother’s lap may require a different sensibility than a landscape, or an illustration taken from a knitting instruction manual. By appropriating style from a critical distance, Faulhaber has the freedom to approach her subject matter from a place of reflection, admiration, humour, or even irony. Like trying on different costumes to match different roles.

One of the vignettes repainted in Ohne Titel (1) is a version of Gritli Faulhaber’s own dot painting, a series titled Militant Joy. In 2020, Faulhaber started painting colourful dots whilst bed-bound suffering from a severe autoimmune disease. Over the years this series has become a kind of coping strategy, whenever she couldn’t work, she could still produce the dots, swearing to only do so, if she couldn’t work otherwise. Ironically, these are maybe the closest Faulhaber has come to cultivating a recognisable painterly signature, and her most sought-after works by collectors. By repainting the sketch-like version in Ohne Titel (2), Faulhaber makes a kind of self-deprecating joke, taking her own subsumption by the art market with humour and grace.

In a constant effort to resist the identity-defining signature, Gritli Faulhaber positions herself against a notion of art history whose conventions and parameters were long defined by patriarchal structures. To reject stasis and embrace a mode of becoming, of fluidity, allows her to explore painting beyond its subject matter, highlighting its socio-political contexts. This inevitably becomes the Gritli Faulhaber’ style.

Repetition/learning: Was verwelkt bereits als Knospe?

Many of the images painted by Gritli Faulhaber are reinterpretations of works by female painters, some well and some lesser known. Over the years, artists like Berthe Morisot, Gerda Wegener, Lotte Laserstein, Pippa Gardener have become familiar figures accompanying Faulhaber’s oeuvre. By re-painting painting, she’s less interested in accurately reproducing a certain image, but will often only hint at it through sketch-like brushstrokes. None of the “aura” of the original is meant to be conjured, instead the motifs gesture towards an original, more like a thumbnail, or a hyperlink, driven by admiration, or affinity. Despite their timeless content, the big flat millennial logic makes itself felt here, too, at certain times, like a Berthe Morisot’s drawing at auction, its slot screenshotted from an iPhone. Similarly to the way images are consumed through screens in the 21st century, Faulhabers’ vignettes allow a viewer to access an image, that only ever refers to, and never substitutes the real.

What is recreated, then, through this gesture of imitation? A certain appeal for these images to be seen, a homage to their existence, and a personal attempt to learning. Gritli Faulhaber is interested in that which is overlooked, or underrecognised. Even in the oeuvre of her idols, she looks for the “B-sides” as she puts it: lesser known works, that seem to question parameters of painting beyond the subject matter. Where painting becomes weird, slippery, reflecting its own social and cultural conditions.

At Theta, Gritli Faulhaber presented amongst a conglomeration of works, a collection of small-scale paintings depicting back-sides of framed canvases. Hinting at the possibility of a painting that has turned its back to the wall, this series seems to hold The Living together as a leitmotif. Titled “1” (What withers already as a bud?), these averted paintings could be read as a critical commentary on art historiography, where visibility has as much to do with gender or class as skill. Even though Faulhaber’s gesture could be neatly packaged as a re-visiting of historical narratives, a re-telling of a canon inclusionary to non-male positions, her interest in the un-seen seems far more sentimental than mere political virtue signalling. I would go so far as to say that Faulhaber’s interest in these images is personal, more immediately driven by feeling. With a certain kind of affection for paintings, not just because they are made by women, but because she in some way feels drawn to the quiet, the not-completely graspable, the visible struggle contained in the type of painting that trips over itself. Images that come up against notions of what a painting should or shouldn’t be: they speak a different language, or as Faulhaber would probably put it, flow by a different rhythm.

* all subtitles are taken from titles of works by Gritli Faulhaber.

March 22, 2024