Some additions to the catalogue of Bernardo Zenale

The oeuvre of the Lombard painter Bernardo Zenale is expanded with some new works and others which have remained on the sidelines of scholarly discussion, all from the last phase of his career during the first quarter of the sixteenth century.

The works by Bernardo Zenale on which this contribution focuses—some unpublished, others known only from old photographs or hidden in the folds of the bibliography—are all from the Lombard painter’s most advanced period, now sixteenth-century. This phase, lasting at least until 1515-1518, provides us with some solid points of reference, yet much of it remains to be understood in its complex creative dynamics. It is a period experienced by Zenale, as always, under the banner of experimentation and characterized by the intelligent study of Leonardo’s innovations, but also by attention to the production of Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Andrea Solario, and the young Bernardino Luini, linked to the Trevigliese master along the 1510s by a solid relationship of work and friendship.

There remains a constant dialogue, initiated as early as the late fifteenth century, woven with Bramantino, who, along with Bernardo Zenale, was the main referent of the Milanese pictorial avant-garde in the first two decades of the sixteenth century, as demonstrated with great clarity by the affair of the protestation that, between 1510 and 1511, pitted the two artists against Giovan Pietro da Corte.

For the sake of clarity, it is worth introducing—albeit briefly—the certified works of Bernardo Zenale’s late activity, which constitute the grid within which the new paintings discussed in this contribution will fit. The sixteenth century opens for the painter, poised between the reception of the Last Supper and the novelties of Bramantino, with the Singing and Playing Angels of the organ choir of Santa Maria di Brera, recently donated to the Pinacoteca di Brera by Antonella and Guglielmo Castelbarco, and placed slightly in advance of the Mocked Christ of the Borromeo Collection, originally accompanied by the date 1502 (or 1503 according to a less accredited reading).

The next foothold is the Cantù polyptych, divided between the John Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Milanese museums Poldi Pezzoli and Bagatti Valsecchi: published in 1507 but in gestation since at least 1502, it is a work that shows Bernardo Zenale in a complicated hand-to-hand with Leonardo’s painting. This moment appears happily surpassed in the paintings that straddle the first and second decades of the 16th century—the splendid Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the chapel of the Blessed Sacrament in San Giovanni Evangelista in Brescia (whose frame was commissioned from Stefano Lamberti in 1509) (6) and the Denver Art Museum’s Sacred Conversation (once signed and dated 1510 on a lost plate displayed in the chapel of Santa Maria della Vittoria in San Francesco Grande in Milan)—in which Zenale juxtaposes Bramante’s year-old cues with the coloristic seductions of Andrea Solario’s painting.

Finally, the Busti altarpiece, a true Luinesque exploit by the master, is dated 1515: a work whose critical vicissitude is intricate, to say the least, and only in recent years has it been traced back to Bernardo Zenale with a greater degree of certainty, thanks to a fortunate documentary finding, which certifies that in 1518 the master received, also on behalf of his carver partner Bernardino da Legnano, the balance of the painting and its frame (8).We will return to this in the final contribution.

After 1515-1518 we no longer have any sure footing; the last stretch of the artist’s career, from the second luster of the 1510s to his death in 1526, is therefore left without firm points of reference: It is a period that sees him documented almost exclusively in the prestigious role of architect of the church of Santa Maria presso San Celso and the Milanese cathedral, consulted for delicate questions of perspective, as in the case of the choir and the altarpiece of the high altar of Santa Maria Maggiore in Bergamo, or for erudite dissertations in the field of antiquarian culture, in which he shared interests and studies with the young Andrea Alciati.

A final certainty, in later years, is Bernardo Zenale’s trip to Rome, which must be dated to after the Busti altarpiece, a work that is still devoid of references to Italian centers, but certainly by 1521, when the master is mentioned among the artists who had returned “fed on speculative contentment to their homelands” from the eternal city in Cesare Cesariano’s commentary on Vitruvius.

A few years ago, I proposed identifying the signs of his descent to Rome, probably carried out together with his friend and colleague Luini, in the Circumcision in the PKB Privatbank and in the complex but fascinating Annunciation in the Pinacoteca di Brera, the two works that most show a modern breath in the maestro’s catalog and that reveal him—despite his old age—still capable of experimenting in multiple directions, under the stimulus of Raphaelesque and Bramante’s innovations.

I hypothesized for them a dating in the last five years, or a little more, of Bernardo Zenale’s activity, so as to distance the two panels from the Busti altarpiece, which in 1515-1518 reveals itself after all – albeit with its heated Luinesque temperature – in full continuity with the works of the early 1510s. This dating, welcomed by only a portion of scholars 13, awaits the feedback of future research, which will succeed in shedding light on the historical aspects of the two panels and in particular on their original provenance.

I have hypothesized for them a dating in the last five years, or a little more, of Bernardo Zenale’s activity, so as to distance the two panels from the Busti altarpiece, which in 1515-1518 reveals itself—despite its heated Luinesque temperature—to be in full continuity with the works of the early 1510s. This dating, welcomed only by some scholars (13), awaits the feedback of future research that will be able to shed light on the historical aspects of the two panels and, in particular, on their original provenance.

If for the Circumcision, a small masterpiece—all autograph—by the elder Bernardo Zenale, we now have a good lead in the direction of the Milanese Jesuit church of San Girolamo (14), in the case of the Annunciation in Brera, an imposing altarpiece which is the fruit of Zenale’s collaboration (voluntary or not) with masters of evident Luinesque extraction (15) (and which arrived in the Braidense collection without any indication of its previous location), two hypotheses of provenance are currently open: the first is the one that would have it originally—also on the strength of the Amadean-style iconography—in the external church of the Augustinian monastery of Santa Marta, destined for the chapel of the Annunciation requested by Bernardino Bascapè in his will of 1523 (16); The second proposal, recently put forward, leads instead to the church of San Lazzaro, a Dominican women’s monastery closely linked to the pious place of Santa Corona and to Zenale himself (the painter’s daughter, Mansueta, entered the monastery as a nun in 1516), where a painting is described between the 17th and 18th centuries that closely evokes the subject of the Braidense panel. It should, in any case, be noted, as we conclude our brief excursus on the problems of dating the master’s final works, that even this second hypothesis takes us well into the 1520s.

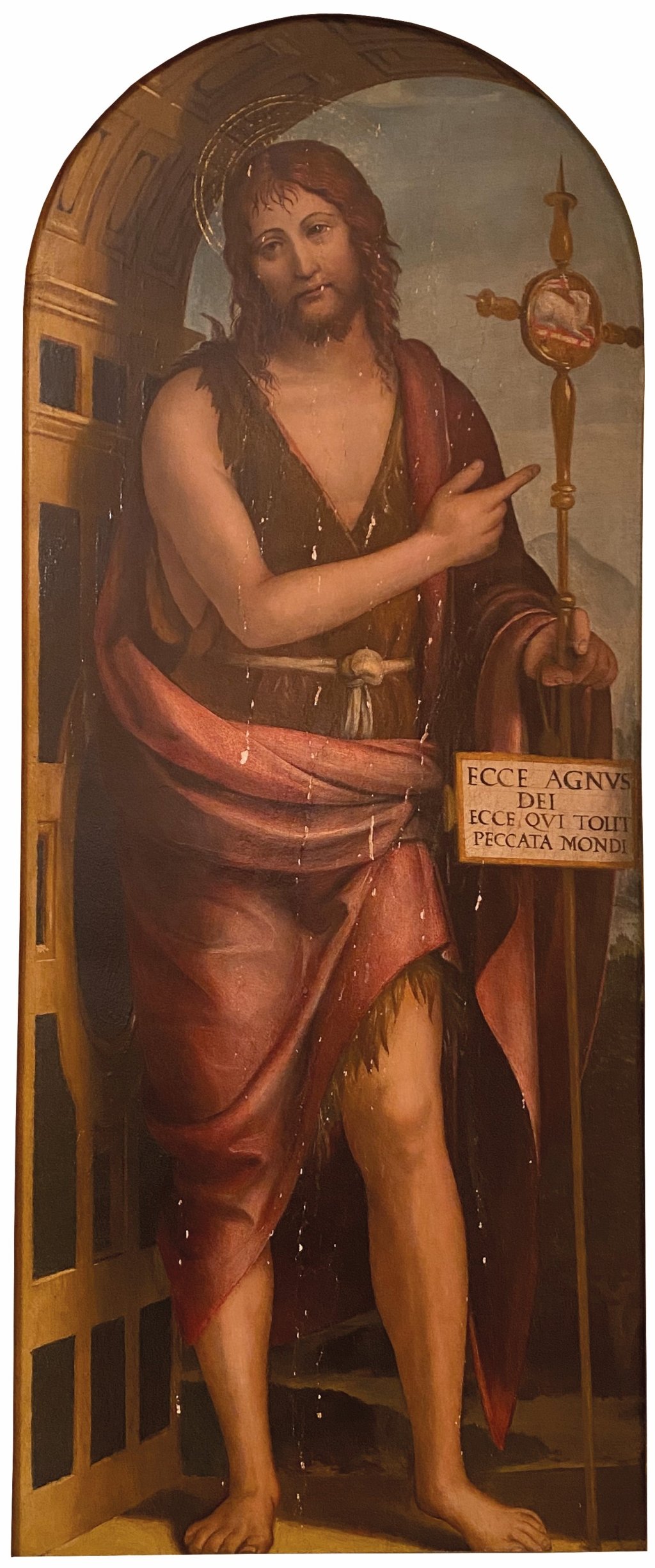

At the end of the first decade of the 16th century, the St. John the Baptist of Downside Abbey is the first work on which we pause.

It is a panel of considerable size (156 x 89 cm) depicting an imposing St. John the Baptist standing against the background of a landscape. The saint is covered by the usual camel skin knotted on the left shoulder and cinched at the waist by a shred of gray fabric. Decidedly skimpy, the robe leaves the Baptist’s chest and legs exposed. Over the saint’s shoulder and right arm rests a large red cloak, much of it slipped on the ground, where it has formed a dense pile of folds. St. John concentrates his gaze intensely on the observer and blatantly points out a detail of the processional cross he holds with his right hand: a small white lamb crouched over a book, alluding to the Lamb of God of the Holy Scriptures.

The reference to the Agnus Dei is further evoked by the inscription in fine capital letters on the large cartouche unfurling heraldically behind the Baptist. It bears the famous passage from the Gospel of John (1:29): ‘Ecce Agnvs dei Qui tollit peccAtA Mundi’. Striking, in the material description of the cross, imagined to be made of gilded bronze, is the naturalism of the Agnus Dei, which bears the bleeding wound on its side, the nimbus and the crusader’s standard, reflecting its identification with the dead and risen Christ.

The desert in which the life of the young Baptist takes place is alluded to by a rugged rock on the left, while in the background, enclosed in the distance by blue mountains, are the loops of the River Jordan. The painting, auctioned on 29 April 2020 at Sotheby’s in London as a work by Bernardo Zenale and purchased on that occasion by the antiquarians Robilant+Voena, comes from the collections of the Benedictine Downside Abbey in Somerset.

The work was donated to the English abbey in 1905 by Sir Henry Hoyle Howarth or Howorth (1842-1923), an important politician and man of culture with wide-ranging interests in the antiquarian and historical fields, through the mediation of Everard Green (1844-1926), Officer of Arms and from 1893 Rouge Dragon Pursuivant of Arms in ordinary. Henry Howarth wrote two letters to him in October 1905, which were published, years after the donation, in the Downside Abbey magazine: the writer of the note, who is anonymous, recalls that it was his intention to give evidence of the donation as early as 1905, but the then Abbot Ford lost Howarth’s letters, which were only found in 1933 and published in that year.

Here are the contents of the two letters, which help to clarify several aspects of the recent history of the work. On 16 October 1905 Sir Henry wrote to Everard Green:

“My dear Green,

My big picture of St. John still hangs in the hall. I bought it in London, but Fairfax Murray, the well-known critic of Italian art, told me he had seen it in Florence. He is the best judge I know, and attributed it to Lazzaro Bastiani, who was a pupil of Andrea Mantegna. It was clearly the altar piece of an Italian church, and is quite unsuited to a private house, but is eminently suited for one of the altars at the new Cathedral. It is painted on a panel, a genuine picture by a master of the 15th century, not otherwise represented in England; and if the authorities would care to have it, as I told you, I should be very pleased to make them a present of it.”

A second letter, dated 23 October 1905, clarifies that the cathedral Howarth writes about in the previous missive is the large church of Downside Abbey:

“In regard to the picture, I should be very pleased if they will have it at Downside if they should care to do so, but I don’t know how far their taste would be for something more modern. I have no doubt about its being quite original and by the artist I told you, for Murray, who mentioned the name to me, had no doubt about it and he is the first authority in Europe. If you think they would care for it, pray, write and ask them and shall certainly have it, for I have very pleasant memories of the place, and it is very interesting to me as the direct descendant of the old Abbey of St. Alban’s.”

The author of the note that appeared in 1933 in the ‘Downside Review’, confirming without a shadow of a doubt the attribution to Lazzaro Bastiani and identifying some similarity between the Baptist and Mantegna’s ‘Madonna Trivulzio’, recalls that two years after the 1905 donation, Sir Henry Howorth also left the abbey a Resurrection of the Venetian school. Going back further than 1905 is not easy. In the papers of Charles Fairfax Murray there does not seem to be any mention of his relationship with Howarth or St. John the Baptist.

The painting, which has regained excellent legibility with the recent restoration, was presented at auction in London already with the correct attribution to Bernardo Zenale, about which there can hardly be any doubt. Infrared investigations carried out on the occasion of the most recent conservation work also confirm the attribution of the work to Zenale without any margin of doubt. The drawing of the saint was transferred from the preparatory cartoon onto the support by means of an engraving, but also rethought in its general arrangement through quick brush strokes applied directly onto the panel, intended to reposition the cross, arms, legs, and cloak of the saint, and to raise the rocks in the background on the left, in a version not followed by the painter in the final drafting.

This type of graphic preparation of the painting is absolutely typical of Bernardo Zenale, who often intervened with a brush drawing directly on the panel, modifying details and settings. Instead, it is worth arguing more thoroughly the dating of the work, which, due to its marked Leonardesque connotation—perceptible in the open landscape setting and the naturalistic rendering of the body and face of the Baptist, the expansion of the forms, and the elegant, supple posture of Saint John, who is very little hirsute—must be placed beyond the ridge of the 1500s, when there was a turning point in the history of the Trevigliese master, so profoundly marked by the study of Leonardo that, for many years, critics relegated the works of that period under the pseudonym of Pseudo Civerchio or Monogrammista XL.

The paintings with which the fine Saint John dialogues best are those that straddle the first and second decades of the 16th century: the Brescia Lamentation from around 1509 and the Holy Family between Saints Ambrose and Jerome from Denver, once dated 1510. In St. John the Baptist, however, one can still perceive the echo of the previous season, represented by the polyptych of Cantù, dated 1507, especially in the painting’s more sober and lowered color range, but also in many more minute details. In this sense, the comparisons that can be established between our panel and the Saints John the Baptist and Francis of Assisi in the Bagatti Valsecchi Museum are useful: for example, in the details of the robes of the two saints, similarly knotted, or the cross, forged in the same metal, with the same reflections. Even bringing the faces of the two saints closer together seems very indicative: there is, in fact, a very similar technique in outlining the beard, hair, nose, and eyes, with the eyelids highlighted by delicate touches of pink.

What does change, however, is the greater physical stature of the Saint John presented here, who—similarly to the bystanders in the Brescia Lamentation—loses the melancholic pose of the saints in the Cantù polyptych, a somewhat gloomy response to Leonardo’s introspections. We can venture, on the basis of the reading proposed so far, a date of 1508-1509, downstream of the Cantù Polyptych (1507) and upstream of the Brescia Lamentation (c. 1509).

The work must have originally stood alone above an altar dedicated to Saint John the Baptist. This is suggested by both the large format and the choice of depicting St. John from a lowered point of view, in a manner that likens the painting to, for example, Boltraffio’s St. Barbara (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, 1502), which was created to decorate an altar in the church of Santa Maria presso San Satiro in Milan in years not far from the panel under consideration here. The St. John the Baptist must have originally been accompanied by a composite architectural frame, and it is worth remembering in this regard, in an attempt to redress the ancient aspect of the work, that from the 1580s and at least until 1510, Bernardo Zenale worked in the territory of the Duchy of Milan in synergy with the De Donati brothers’ workshop for the supply of frames. Only in the case of the later Busti altarpiece are we aware of a different partnership, linking the master to the wood sculptor Bernardino Corio da Legnano.

To get an idea of what the frame of St. John might have looked like, we can turn to two works that came out of the De Donati workshop in the same years as our painting: the organ case in Monza Cathedral and the altarpiece in Caspano di Civo, in Valtellina, both of which date back to 1508 and present the same Bramante-esque measure, with ample decorative inserts in the classicist style.

It is by no means easy to identify the original location of the painting, probably, as mentioned above, made for an altar dedicated to the Forerunner in Lombardy. Having ruled out a series of hypotheses arising from work on 17th-18th century Lombard guides and set aside the possibility of the panel’s provenance from the prestigious Milanese headquarters of the Knights of Malta, who were particularly devoted to St. John the Baptist (the work is, moreover, devoid of the symbols of the powerful military order), a promising avenue of research has emerged that stems naturally, so to speak, from an analysis of the painting’s subject.

I refer to the possibility of its ancient relevance to the Certosa di Garegnano, the Carthusian Monastery of Milan, founded in 1349 by the archbishop and lord of Milan Giovanni Visconti and dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption and St. Ambrose, as well as to the Agnus Dei; a title, the latter, with which the monastery is always referred to in documents. It will not have escaped the reader’s notice that it is precisely an Agnus Dei that is particularly carefully detailed and the symbol that St. John points out to the public with a broad gesture; to the same theme alludes emphatically—as mentioned above—the scroll that unrolls behind the saint.

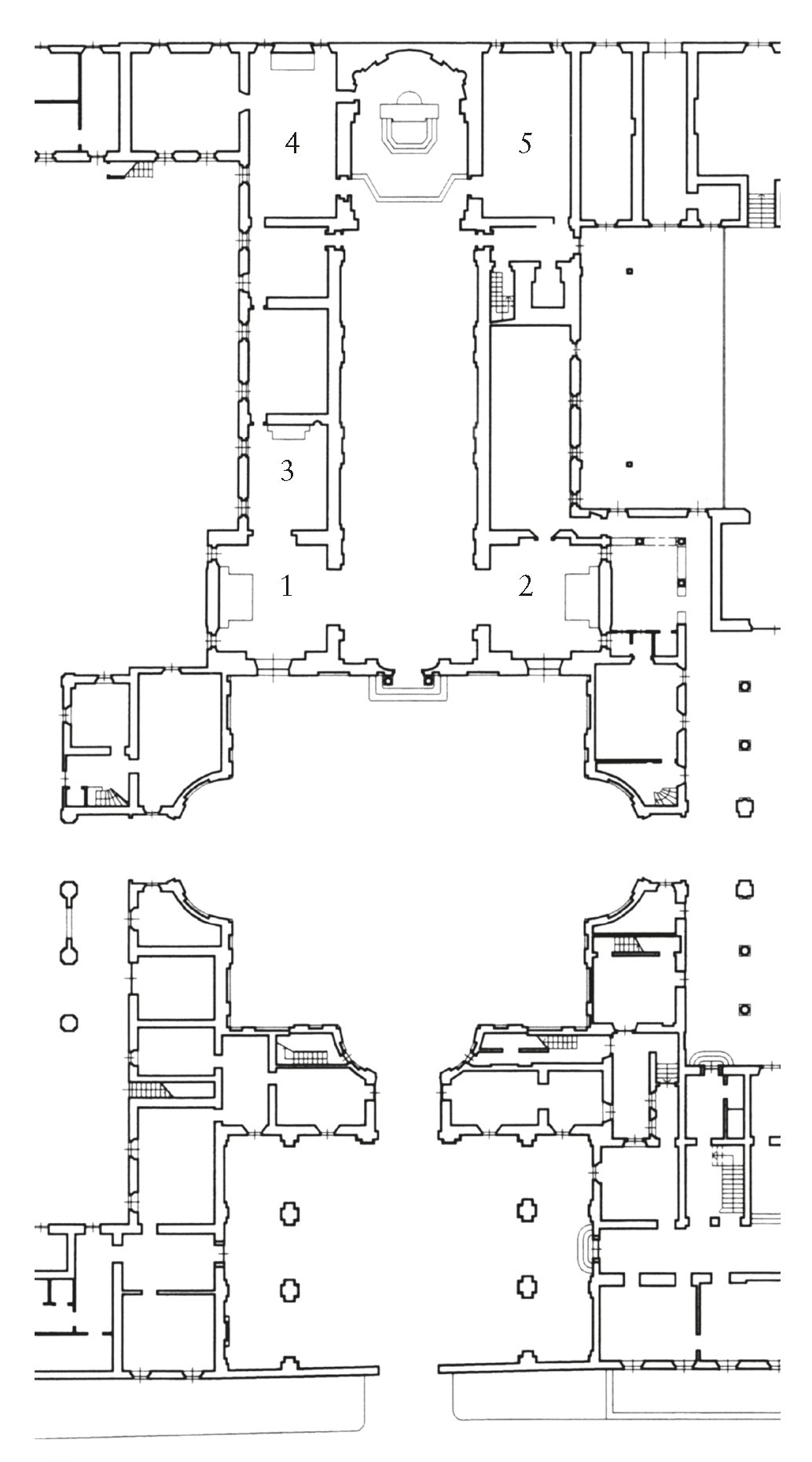

The Certosa di Garegnano is best known for the significant interventions that redeveloped its appearance between the late 16th and early 17th centuries, including the frescoes by Simone Peterzano and Daniele Crespi, and the architectural work on the façade and the monastery (particularly the large cloister) led by architect Vincenzo Seregni. Almost every element of the original 14th-century Carthusian monastery settlement in Milan, as mentioned by Francesco Petrarch, has been lost. However, there is a very faint trace—found in documents and some architectural and pictorial fragments that have re-emerged through restoration work—of the phase that immediately followed, dating from the 15th and 16th centuries. This phase must have had a profound impact on the appearance of the Charterhouse, both the church and the monastery, but is now almost forgotten amid destruction and transformation.

Focusing now on the church and its altars, the creation and transformation of several chapels (primarily those on the left side and the first on the right side), the chapter house, and the sacristy—all spaces that still exist in their volumes, though further modified over the centuries to update them to changing tastes (33)—occurred between the 15th and 16th centuries. Examination of the documentation relating to the important religious settlement preserved in the Braidense Library and the State Archives in Milan first allows us to rule out the existence of a presumed chapel dedicated to John the Baptist as early as 1407, as reported by almost all the bibliography relating to the Charterhouse (34). The chapel that in 1407 Zenone de Freganesco da Cremona requested from the prior and the monks of Garegnano to be built where they preferred was in fact dedicated to John the Evangelist and not to the Forerunner: the deed records it as “unam capellam de bonis lapidibus […] sub vocabollo et nomine beati Iohannis Evangeliste” (35). It was later built to the left of the entrance to the church, slightly distant from it (therefore, at that time outside the body of the church), not far from 1425, when it was consecrated and is remembered as ‘nova’, just completed.

Specular to that of the Evangelist, the chapel of St. Anthony Abbot was to be built years later—of the utmost interest to us, as we will shortly understand—left as a testamentary charge to his heirs by Giovanni del fu Antonio Conti (de Comitibus) of Lonate Ceppino in his two wills of 27 August 1467 and 24 August 1469. Conti’s last will requested that within ten years of the death of his direct heirs, the brothers Antoniola and Ubertino, the substitute heirs named by the testator (the children of his uncle Federico: Beltramolo, Battista, Tommaso, and Giovanni Antonio) have “a chapel built in monasterio Cartuxie de Garegnano videlicet a manu dextra introytus porte ecclesie dicti monasterii et in illa latitudine et altitudine ac longitudine et grossitudine muri prout est altera capella Sancti Iohannis que est a manu sinistra porte dicte ecclesie sub vocabulo Sancti Antonii”. They are to commission for the chapel a painted panel and a missal worth 80 and 160 imperial lire respectively (“ma yestas una picta de valoris librarum octuaginta imperialium. Item missale unum valoris librarum centum sexaginta imperialium”), and also a chalice, a planet with its furnishings, and a bundle of velvet, each worth 40 imperial liras.

The prior and the monks of Garegnano (in the second instance, also the Scuola delle quattro Marie) are called upon to oversee the correct implementation of Giovanni Conti’s requests. It is worth mentioning in this regard that in the years 1455-1456 and 1465-1476, Don Cristoforo Conti is often documented as prior of the Charterhouse of Garegnano, whom the surviving documentation in the State Archives in Milan allows us to identify as Giovanni’s brother. He had made his profession between 1444 and 1447 and, in February 1479, the year of his death, had passed to the Charterhouse of Pontignano near Siena. He is remembered with high honors by historians of the Carthusian order.

It is probable that the request to have a chapel built mirroring that of the Evangelist carried with it, in the intentions of Giovanni Conti, well-directed by his brother the prior of the Charterhouse (39), the idea of transforming the entrance to the church, defining even then the curious inverted T iconography that characterizes the plan of the building and which clearly conditioned the subsequent design of the façade (40). If the notes in Conti’s will, which entrust the construction of the chapel to the substitute heirs (and not to the direct heirs), already suggest a considerable delay, certainty in this regard can be deduced from the important memoir that enumerates in detail the consecrations of the altars of Garegnano and is conserved in the Braidense Library in Milan. It records the consecration, on 23 February 1509, of the altar […] “capelle nove ad honorem Dei et Beatissime Virginis ac omnium sanctorum et specialiter ad titulum Sancti Iohannis Baptiste, et Sancti Antonii abbatis”. The chapel in 1509 is called ‘nova’, so it must have been newly built and decorated. It is definitely important to emphasize the double dedication of the sacellum, including the dedication to the Forerunner, certainly in homage to Giovanni Conti; obviously, a very significant fact for us.

The construction and decoration of the chapel of Saints Anthony and John the Baptist—which, as we have mentioned, implied the necessary transformation of the façade of the church—around 1509 is also a significant datum for the Renaissance building site of the Milanese Charterhouse. In these years, not by chance, there was a notable intensification, marked by the commission to Benedetto Briosco in 1509 for a consignment of 68 Carrara marble columns, followed in 1510 by a similar contract with Pietro di Matteo Casoni of Carrara for an additional 40 columns.

What has been reconstructed so far regarding the chapel of Saints Anthony Abbot and John the Baptist, based on the documents, clashes with the evidence of the facts: if we visit the Certosa di Garegnano today—although the situation was similar from the end of the 16th century—the chapel of Saint Anthony Abbot and Saint John the Baptist is no longer located in the first chapel on the right (which, as we will see, was dedicated to the Annunciation and to the Virgin of the Rosary between the 16th and 17th centuries) but in the second chapel on the left side. We must consider the extensive changes made to the Charterhouse of Milan in the post-Tridentine era, when many of the altars at Garegnano had to change dedication. The chapel to the left of the entrance remained dedicated to John the Evangelist until the early 17th century, when it was rededicated (1617) to Saints Bruno and Hugh. The chapel on the right, however, was re-consecrated, with its new dedication to the Annunciation and the Rosary, in 1597, a year after the altarpiece by Enea Salmeggia was created, and again in 1617, in conjunction with the execution of the new altar, dated 1615. All traces of the ancient Renaissance decoration, which was probably extensively modified between the late 16th and early 17th centuries during the creation of the aforementioned altarpiece and altar, disappeared in the second half of the 18th century under the frescoes depicting the Mysteries of the Rosary by Biagio Bellotti.

With the transformations made around 1597 to the first chapel on the right, the dedication to Abbot Anthony and the Baptist was transferred to the second chapel on the left side. This chapel is not recorded in the memory of the consecrations but features a cycle of frescoes depicting stories of Saints Anthony Abbot and Paul the Hermit from the early 17th century, which Simonetta Coppa has cautiously attributed to Carlo Antonio Procaccini (48). Beneath the frescoes are remnants of decorative paintings from a few (but not many!) years earlier, possibly the initial decoration of the chapel from the late 16th century. On the altar, which dates from the 19th century, there is now a painting of the Holy Family attributed to Carlo Francesco Nuvolone and donated to the church of Garegnano only in 1910. An early 20th-century photograph shows the same altar with a slightly different altarpiece, adapted to accommodate a statue, apparently from the 19th century, of the Madonna and Child. The original altarpiece, which was undoubtedly dedicated to the Baptist, is missing.

Due to their secluded location, the Chapel of St. Anthony and the next two chapels on the left side were used exclusively by Carthusian monks for their own devotion in the 17th and 18th centuries and were never open to the public. This explains the lack of information about the pictorial decorations of these chapels. An ancient guide to the Charterhouse recalls that even in the 19th century, these chapels housed very rich altars, one of which was described as being “of the finest ivory worked by a master’s hand,” though its current whereabouts remain unknown.

The probability that Bernardo Zenale’s altarpiece under consideration here was originally intended for the chapel commissioned by Giovanni Conti and subsequently experienced transformations in the years following the Council of Trent is quite high. This is due not only to the subject matter and the perfect alignment of dates (the altar was consecrated in February 1509, and the panel can be dated stylistically to this exact period, between 1507 and 1509), but also to the presence of Bernardo Zenale’s workshop at the Certosa in the years immediately following: notably, the beautiful Saint Michael the Archangel piercing the devil on the vault of the chapter house in Garegnano, discovered about twenty years ago and attributed to the Trevigliese master by Sandrina Bandera. While the invention is impressive, the execution does not seem attributable to Zenale himself but rather to a figure associated with his workshop. The decoration of the Chapter House, for which a date in the last decade of the 15th century has also been proposed—too early to account for the type of perspective experimentation evident—along with the looser pictorial execution, can be linked to the consecration of the room on 25 August 1508. This provides further evidence of Zenale and his workshop’s presence in the significant Milanese religious context during the period of the execution of Saint John the Baptist.

A possible interlude: Bernardo Zenale at work for Marshal Trivulzio in Vigevano Castle?

A little after Saint John the Baptist, in the years of the Denver altarpiece and the enigmatic Lampugnani Circumcision (Paris, Musée du Louvre), one must place a possible intervention by Bernardo Zenale in the Castle of Vigevano, at that time the prerogative of a nodal figure of the French Milan, Gian Giacomo Trivulzio. The only trace left of these high-ranking works is a battered fresco, recently published by Luisa Giordano following the latest restoration from 2018-2019. It is located in the first room of the body of the building that forms the base of the castle’s falconry and now houses the rooms of the National Archaeological Museum of Lomellina: a square-shaped room, covered with a vault lowered on hooks. The fresco on the western wall of the room, which is rather small in size, is very lacunose and abraded, in many places reduced to under-modeling or drawing. Investigations carried out in 2018-2019 on the ancient plasterwork of the room and on that of the adjacent rooms were unsuccessful, and thus we have no concrete evidence of the existence of other frescoes around the surviving one. Introduced by a simple faux-marble frame, soberly decorated with candelabra motifs, the painting depicts the Adoration of the Child in the presence of two men of age, one in front and the other in profile, both leaning on a broadside. If we can identify the first as Saint Joseph, also because of the evident presence, in trace, of the halo, the ruin of the pictorial film prevents us from being certain about the elderly man in profile, perhaps haloed. We can only try to propose an identification for him as Saint Jerome.

The sacred subject is set within an impressive architectural frame, filled with tall columns on the left and marked on the right by the presence of a reinterpretation of the Roman Torre delle Milizie (Tower of the Militia).

Luisa Giordano, when discussing the attribution of the battered fresco, does not fail to point out a reference to Bernardo Zenale for the figures and to Bramantino for the landscape and architecture, coming to the conclusion that it may be a follower of the two masters active at the beginning of the second decade of the 16th century.

That the author of the fresco can be identified in Bernardo Zenale alone, albeit with all due caution, can be deduced from the comparison that can be made with works painted in the first decade of the 16th century by the Trevigliese painter, such as the Denver Altarpiece and the Lampugnani Circumcision, especially with regard to the physiognomy and modeling of the saints. Comparison with the only remaining visual trace (an old photograph) of one of the lost frescoes with Stories from the Passion that decorated the Cloister of the Dead in Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, recalled with high praise by Vasari and Lomazzo, or with the drawing in the British Museum in London preparatory to the scenes of the Christological cycle, proves particularly useful (56).

In both cases, the architectural backdrops within which the Gospel narration is staged reveal several affinities with the setting of the Vigevano fresco. The piece of underdrawing that has re-emerged under a large gap in correspondence with the two elderly saints can also help us to confirm—with its free and quick brushstroke—the attribution of the painting to Zenale (57).

During the 1510s: Additions, Reconsidered Works, and the Problem of the Old Bernardo Zenale’s Workshop.

The three small circular panels on which we will now focus date from the second half of the 1610s. They are not unpublished works: they simply emerged very early, as we shall see, from the critical debate on Bernardo Zenale. They depict the Eternal Father, the Announcing Angel, and the Virgin Announced (their diameters measure 22, 23, 23 cm respectively) and are to be originally thought of as being in the cymatium of a single-field altarpiece or polyptych, in all likelihood triangular in shape, to represent the Annunciation scene as a whole.

At the top center would have been the Eternal Father between heads of seraphim; at the bottom sides would have been the Announcing Angel, holding the lily in his left hand, and the Virgin Annunciate, caught in the act of reacting to the angelic message by rising from her seat with eloquent gestures and kneeling down. This is the only figure to receive a setting within a sort of study, set up with a lectern and a seat with classical profiles. In the case of the Angel, however, the only hint of spatiality is the shadow cast, defined by hatching.

All the figures are realized in gold. Only in the case of the Announcing Angel and the Virgin Announced does the gold appear to be outlined in black along the margins, to mimic the thickness of the clypeus. Overall in a good state of conservation (the Announcing Angel shows more signs of distress), the tondi have recently been restored

The first news of the three paintings dates back to 1963 when they were auctioned at the Milan branch of Finarte (61). According to a tradition pointed out to the new owner at the time of purchase in the same 1963 (62), the ancient location of the panels should be identified in the Cascina Pozzobonelli in Milan; the works would then have passed into the collection of the architect Luca Beltrami and then to the latter’s heirs, before appearing on the antiquities market after the Second World War.

I have investigated for some time, but without appreciable results, the path opened up by this indication (63). It is, of course, possible that Beltrami acquired the three roundels while in charge of the Lombard farmhouse, but at present there does not seem to be a tangle to unravel this skein. If adequately proven, the ancient provenance from the Pozzobonelli villa could prove to be of the utmost interest. The building, of which only part of the portico that leads into the small triconca chapel and the chapel itself remains today, is, in fact, one of the most interesting examples of Bramante’s architecture in Milan, from time to time attributed to the design of the Urbino master himself or, more likely, to one of his close followers. The villa was built and decorated with interesting graffiti in the first decade of the 16th century by Gian Giacomo Pozzobonelli (65). The subsequent history of the family remains to be investigated, which could also shed light on the possible commissioner of the three paintings, which can be placed, as will be better specified shortly, in the second decade of the 16th century.

The first mention of the works can be found in the 1963 auction catalogue, in which the judgment of the illustrious commission assembled for the occasion, comprising Enos Malagutti, Giovanni Testori, and Carlo Volpe, is reported. The three scholars put forward the name of Bernardo Zenale in his advanced phase (67), a moment in the Trevigliese master’s history brought into focus by Maria Luisa Ferrari a few years earlier, returning to the painter’s maturity the corpus of paintings then attributed to the so-called Pseudo Civerchio or Monogrammista XL.

It was Ferrari herself, in a further article dedicated to Bernardo Zenale in 1967, who published the three panels in a scholarly context and placed them close to the Deposition of the Trevigliese master in San Giovanni Evangelista in Brescia. Years later, in 1977, Paola Astrua, in a laconic note, denied the works to Zenale, to whom Giovanna Carlevano returned in 1982, admitting, however, that she was unable to date them. The last mention of the paintings dates back to 1994, when Pierluigi De Vecchi gave a further negative opinion—on the basis of the images alone—regarding the Zenalean autobiography of the three roundels.

The works, known until recently only through the small black-and-white images published by Maria Luisa Ferrari in 1967, have not been mentioned since. Their critical history has thus not so far been able to benefit from the further step forward made by studies on Bernardo Zenale’s advanced phase with the discovery of the deed that records the balance of money awarded to the painter for painting the Busti altarpiece, a work long debated in critical circles between the master and Bernardino Luini.

The panel is dated 1515 on the step of the throne, while the deed found at the State Archives in Milan is dated 1518, a fact that allows the completion of the work to be perhaps delayed by some time. The document also mentions a master Bernardino, identifiable—as already mentioned—as the carver Bernardino Corio da Legnano, certainly the author of the work’s frame, who was also active with Bernardo Zenale in the building site of Santa Maria presso San Celso and linked to him by a certain friendship, given that he appears in 1516 with Bernardino Luini among the witnesses at the monkhood of the master’s daughter in the Dominican monastery of San Lazzaro in Milan.

It is precisely in the vicinity of the Busti altarpiece that the three tondi considered here seem to find their proper collocation. Compare, for example, the faces of the Annunciata, formerly Finarte, and the Madonna Enthroned in the Braidense altarpiece, or the ample drapery of God the Father with those that cover the Virgin in the Busti panel, similarly conceived, both in the softness of the broad folds dense with color, and in the chromatic range, which is absolutely identical.

On the other hand, it is more difficult to compare the Announcing Angel, which—even net of its less felicitous state of preservation—seems to be attributable to a personality distinct from that of the master, who conceives the drapery differently and realizes the chiaroscuro in hatching.

The stylistic proximity between the tondi and the Braidense altarpiece is such that it raises the doubt—destined to remain so for the time being—that the three pieces were once part of the painting commissioned by Busti for his own chapel, dedicated to Saints James and Philip, in the Milanese seat of the Umiliati. The large panel has come down to us without the frame that the carver Bernardino da Legnano had prepared. That it was an architectural frame is confirmed by his knowledge of early 16th-century Milanese working practices, but also by the remarkable mock architecture designed to frame the sacred conversation in which the kneeling Busti family participates. The Braidense altarpiece measures, without the frame, 195 x 145 cm and therefore the presence of the three roundels, some twenty centimeters in diameter, in the cymatium would not be obstructed.

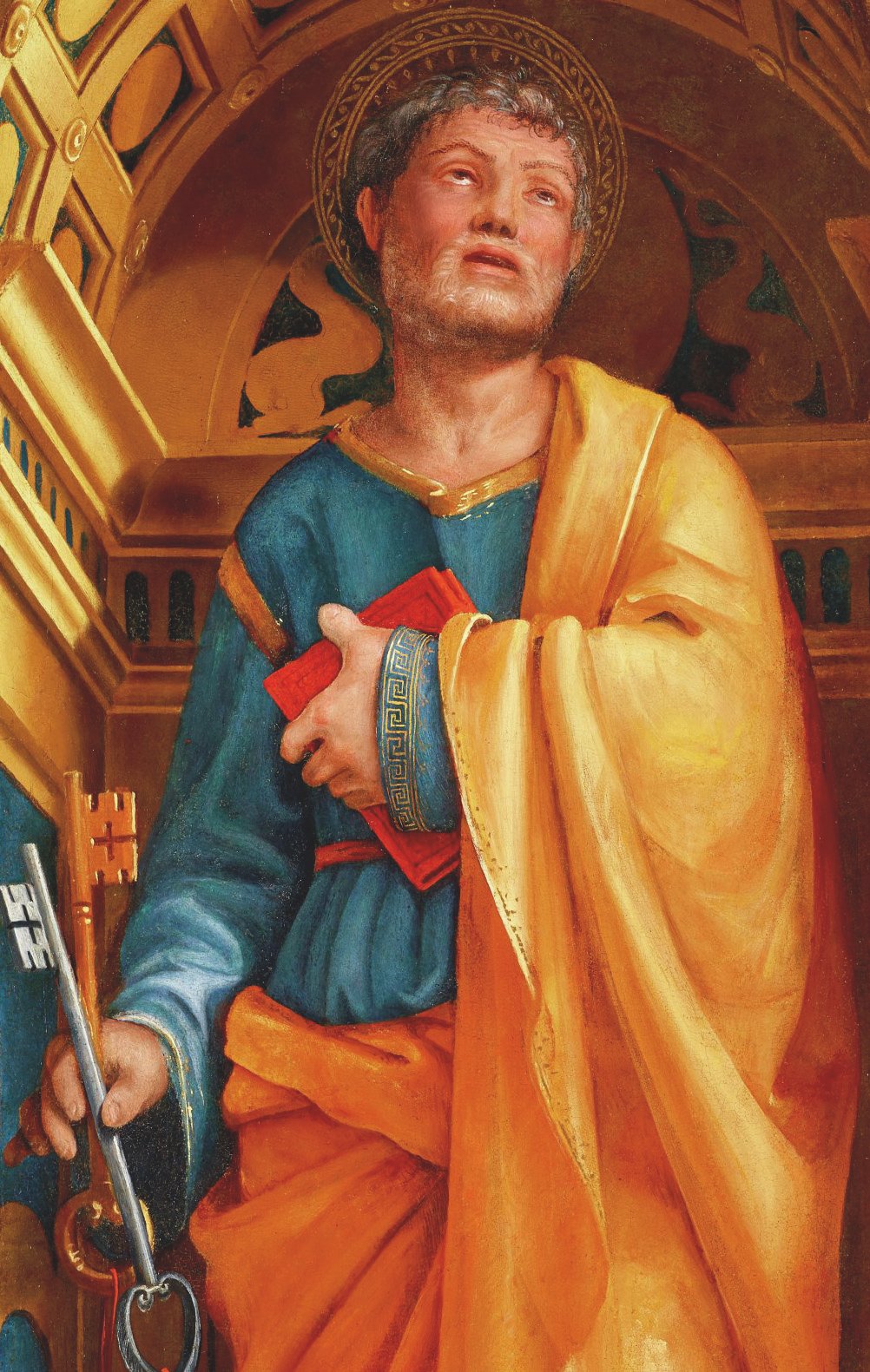

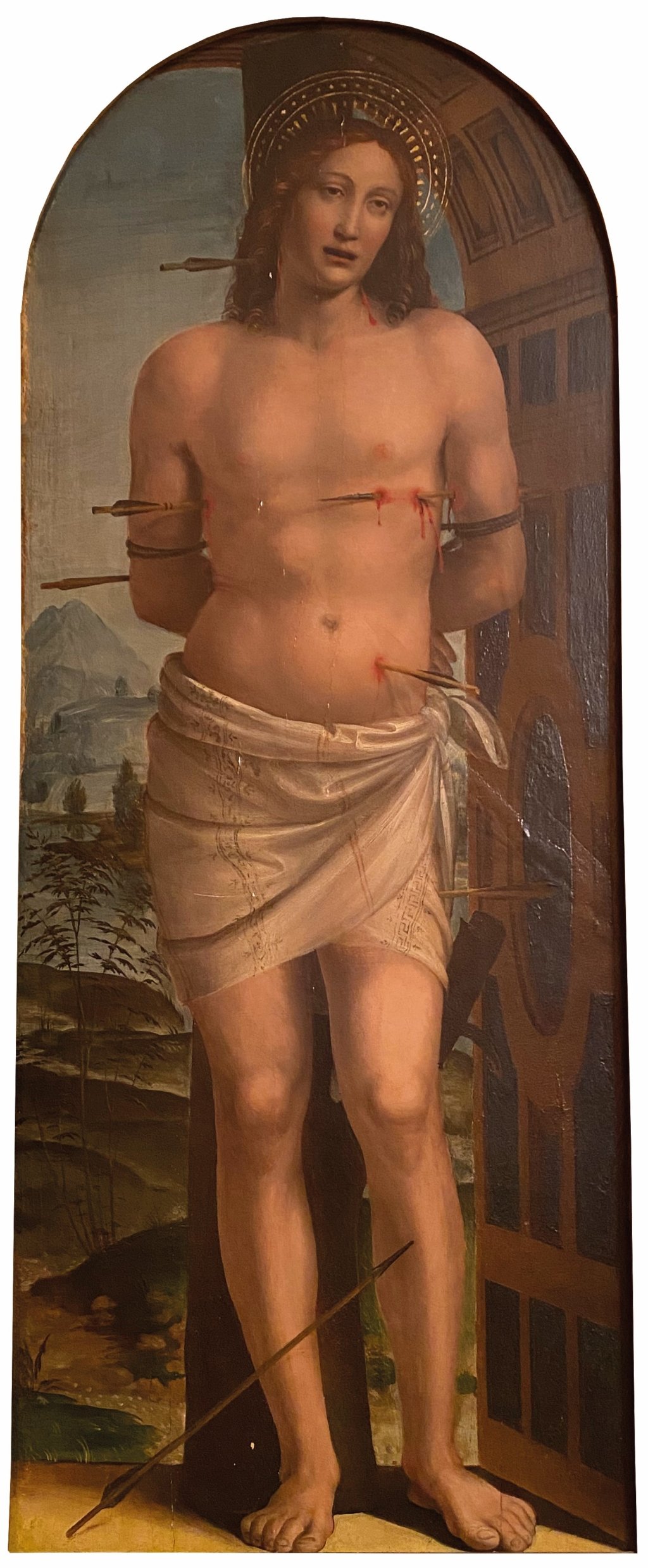

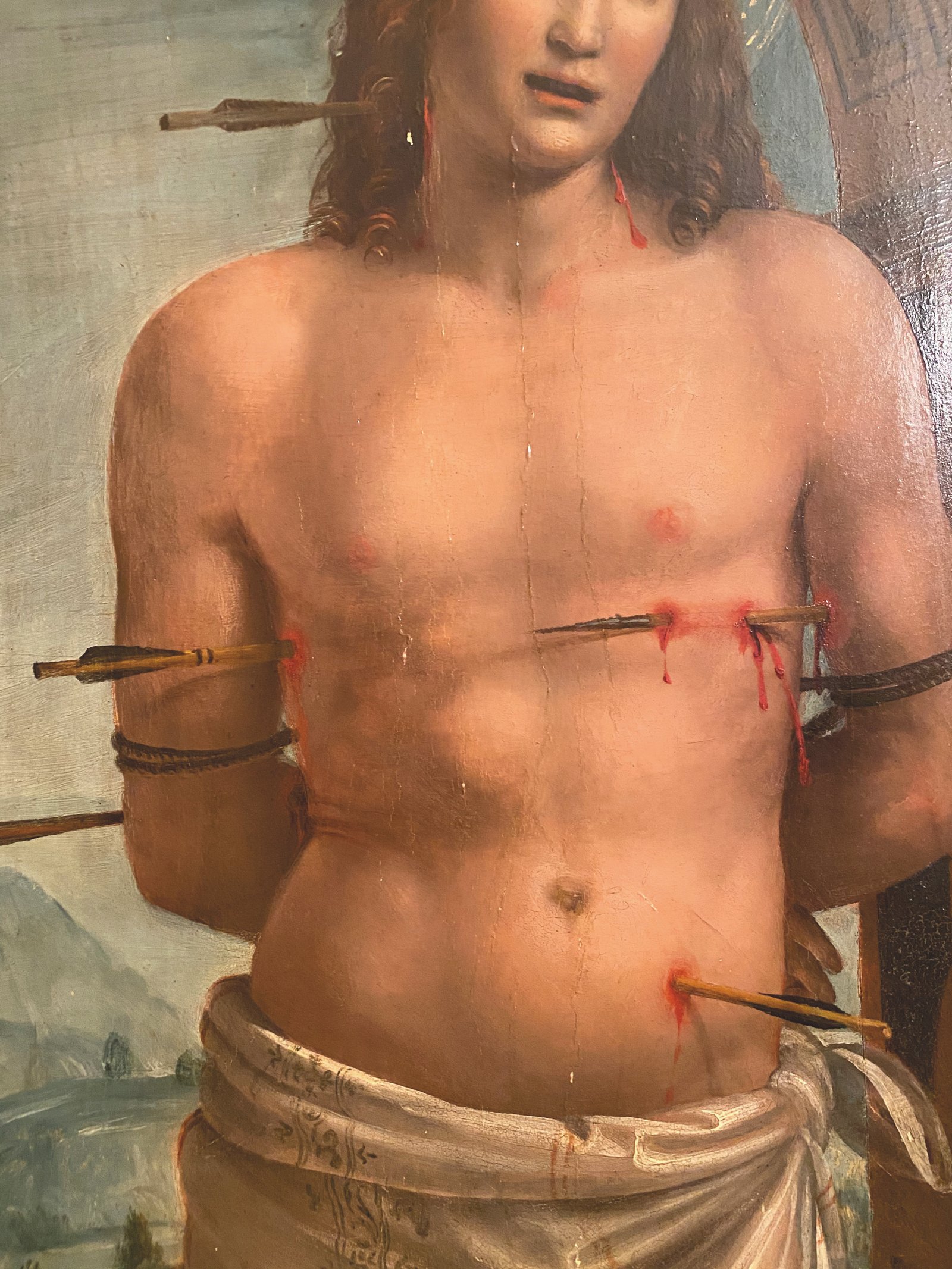

Not far from the Busti altarpiece is also the polyptych partially re-assembled a few years ago by Giovanni Agosti, Jacopo Stoppa, and Marco Tanzi, placing alongside the St. Peter from the Birmingham Museum of Art and the St. Michael Archangel formerly by van Marle a St. Sebastian that an old photograph recalls in the Venino collection. It is now in a private collection in Milan, together with its pendant: a St. John the Baptist portrayed below the same claustrophobic lacunar vaulting, against the backdrop of a landscape of mountains, with clearly visible in his left hand, in addition to the cross with the symbol of the Agnus Dei, an ansata table bearing the inscription: “ecce Angvs / dei / ecce Qvi tolit / peccAtA Mondi”.

Restored in the second half of the 20th century, the two pieces are differently preserved, where the Baptist shows some obvious cracks and distressing, caused by the rigid parquetry applied on the back, while the St. Sebastian reveals a better state, only obscured by an altered patina.

The original provenance of the two panels is not known, nor is there any information to direct our research. The polyptych thus reassembled, lacking the lower and upper centers and the plausible cymatium, bears at the bottom Saints John the Baptist (indicating for certain a Madonna and Child) and Sebastian, and at the top Saints Peter and Michael the Archangel, unfortunately all saints of widespread devotion. However, it should be noted that John the Baptist and Michael are particularly dear to the Umiliati, an order for which Bernardo Zenale worked throughout his artistic career.

The same can be said for Peter, to whom two important Humiliated domus were dedicated within the Milanese diocese: the well-known San Pietro in Viboldone, governed in years that are interesting to us, until 1523, by the remarkable personality of Ludovico Landriani, an expert in Vitruvian science cited on a par with Bernardo Zenale by Cesariano in his commentary on Vitruvius and responsible for the construction and decoration of the prior’s house in Viboldone; and San Pietro in Monforte, in Porta Orientale in Milan, a context that is difficult to reconstruct, which passed to the Somaschi Fathers after the suppression of the Humiliati.

In the case of this polyptych, as in that of the three roundels, it is worth noting, alongside Bernardo Zenale, who governs the whole by providing the drawings and reserving the execution of some particularly effective passages, the presence of a workshop assistant of more distinct Bramantesque and Luinesque connotation, responsible for a large part of St. John and perhaps, but the state of the painting does not help to clarify ideas, of St. Michael formerly van Marle. Zenale’s hand, on the other hand, can be clearly distinguished in the St. Peter of Birmingham—in the glare of the light on the architectural envelope, in the lightness of the saint’s yellow cloak, with its ecstatic pose—and in some fragrant details of the St. Sebastian, for example in the drapery of the loincloth and in the detail of the arrow penetrating the side of the body, lifting the saint’s pink flesh, all features that bring the polyptych in question closer to the Circumcision of the PKB PrivatBank.

It has been seen how, when dealing with Zenalian works after 1510-1515, it has often been necessary to invoke the presence, alongside the master, of helpers with more or less distinct personalities. It is a theme, that of the workshop of the Trevigliese, which has been put forward critically since the Bernardo Zenale and Leonardo exhibition in 1982 by various scholars and is particularly insistent in the last fifteen years of the master’s career, when there is a proliferation of works with a strong Zenalian connotation, but which cannot be ascribed to the painter in their entirety, except for invention and perhaps some details. I am thinking, to cite further examples, of the Madonna of the Roses in the Oleggio Religious Museum or the ‘Madonna Cusani,’ a fresco detached from the Milanese Dominican monastery of the Vetere and deposited by the Pinacoteca di Brera in the Museum of Science and Technology in Milan, or the Madonna and Child in the National Gallery in Parma or the Carmelite Saint Albert of Sant’Agata del Carmine in Bergamo; but also to an easel painting such as the Noseda Suckling Madonna in the Pinacoteca Braidense, which has never fully convinced scholars of its authorship.

The increasing emergence of collaborators and apprentices alongside the master from the second decade of the 16th century onwards is certainly not coincidental. In these years, Bernardo Zenale’s painting commissions were flanked by architectural ones, and it is inevitable that an articulate workshop must have flanked the busy master in the handling of painting commissions. However, this topic is not easy to explore, not only because of the lack of studies on the organization of the workshops of Lombard painters between the 15th and 16th century.

Alongside the problem of Bernardo Zenale’s workshop, there is, in fact, the further question of the societies formed by the old master with established or emerging artists. This is the well-known case of Bernardino Luini, who emerges in the decoration of the chapel of St. Joseph once in Santa Maria della Pace in Milan (Milan, Brera Art Gallery), but also in the frescoes in the vestibule of the Certosa in Pavia, or in those—just mentioned above—in the Dominican monastery of the Vetere. Another case is perhaps that of the very young Nicola Moietta, which should be carefully investigated in the future, bearing in mind the important openings by Francesco Frangi and Federico Cavalieri on the triptych of San Mattia alla Moneta (Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana).

Alongside these phenomena, so to speak, intrinsic to Bernardo Zenale’s last activity, the second decade of the 16th century also saw a renewed moment of fortune for the painting of the Trevigliese artist, with the emergence of a following of epigones. By way of example only, I would recall the fresco depicting the Madonna and Child, Saints, and the patron Nicolas de La Chesnaye in the Bramante sacristy of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

Without any pretense at completeness, I would like to dwell on this occasion only briefly on the problem of Bernardo Zenale’s close workshop, carrying out a renewed analysis of the Busti altarpiece, a work that entered the master’s catalog some years ago as a totally autograph painting, given the documentation published in 2002. However, previously, starting with Paola Astrua’s openings in 1982, it was attributed—even by those who no longer sided with Luini or a follower of Luini—mainly to a collaborator of the Trevigliese master, identified by some scholars at work on the Oleggio canvas as well.

If we approach—albeit aware of the recently published archive documentation—the Braidense altarpiece, we are forced, in spite of everything, to note some significant differences between the Busti altarpiece and works of certain Zenalian ascription close in chronology, such as the Lampugnani Circumcision, upstream, and the PrivatBank PKB, downstream.

Above all, when analyzed with care and in detail, the Braidense altarpiece reveals substantial internal differences between the different parts. These differences are evident if we place the swollen, densely colored drapery of the Virgin and, in part, of St. Philip alongside the silky, loose, completely Luinesque drapery of St. James; or if we compare the feet of the two twin saints (the one on the right very Bernardo Zenale an, the other thinner and without body); or again, if we observe the design of the hands of Saint James, long and without backbone, so far from the lively and expressive hands to which Zenale’s autograph production has accustomed us.

In short, I believe that in the Busti altarpiece, alongside the elderly master, there is a personality who, although showing a certain autonomy and a more marked Luinesque and Bramante-like quality, acted under the careful supervision of the master painter. We can identify her most clearly in the St. James, but she must also have operated in other points, later made homogeneous with targeted interventions (90).

I wonder if it is not also due to his presence that the blatantly Luinesque quality of this painting is perceptible, particularly in the two side saints and decidedly less so in the Madonna and Child, certainly the most Zen-like insert of the work. All around the Busti altarpiece, which stands as a particularly representative example of the workshop problem because it is documented as having been paid to Zenale, are also the frescoes and panels just mentioned above, which have long gravitated critically around the name of the artist from Treviso.

At this juncture, all set in the 1610s, the presence alongside the master of Gerolamo Zenale, the artist’s son who had embarked on a painting career right at the end of the first decade of the 16th century, must be taken into serious consideration. In 1509-1510 he was probably involved in the building site of the chapel of Sant’Ambrogio della Vittoria in San Francesco Grande, from which the altarpiece now in the Denver Museum of Art came, and which also included a cycle of frescoes; in 1511 he signed the above-mentioned protest in favor of Bernardo Zenale and Bramantino; he was then active in the San Celso building site alongside his father, whom he often substituted in delicate economic affairs; he died of the plague at the end of 1520 and, according to Lomazzo, Zenale dedicated one of his lost treatises on perspective to him in 1524.

Although the recent attempts to identify—in Zenale’s late works—the personality traits of his son Gerolamo are certainly stimulating, I believe it is necessary for now to stop at an awareness of the problem, trying to recover further documentary, chronological, and stylistic props useful in order to clarify and distinguish the different interventions.

January 22, 2025